A few years ago, I went with a friend to a nomad festival in southeastern Kazakhstan. Though it was just ten miles or so outside the bustling metropolis of Almaty, you could easily imagine yourself transported a thousand years back in time. Dozens of yurts billowed like clouds across the verdant steppe, colorful streamers and banners flapping in the breeze. Horsemen with lances and battle axes trotted by. Women in regal gowns and headdresses bedecked with coins moved slowly through the crowd, the coins’ silvery jingle adding a subtle music to all their movements.

At a stand attended by an old grandmother with an enormous wooden ladle, we bought a two-liter bottle of koumiss—fermented horse’s milk that is slightly and pleasantly alcoholic. Sipping our koumiss we wandered over to the traditional archery tournament where competitors from all across Central Asia let fly volleys of arrows at distant targets. A number of these archers were women, including one with such a commanding presence that the crowd parted in front of her wherever she walked. The women archers mixed with the men and shot with the men. I asked my friend Arman about this. He said it was normal.

The presence of these women archers at the fair was not a concession to modern ideas of sexual equality. In fact, the tradition of women warriors in Kazakhstan goes back thousands of years to the ancient Scythians. As Adrienne Mayor has irrefutably demonstrated in her book The Amazons, the myriad stories about exotic women warriors and women archers that so enthralled ancient Greece—long thought to be the stuff of myth—were actually true, as scores of recent archeological discoveries have documented. These “mythical” women warriors, the Amazons, were part of the sprawling Scythian culture and its offshoots that dominated Central Asia and jutted up against the farthest outposts of ancient Greece, beginning in the seventh century BCE. Meyer also specifically traces many of the ancient “Amazonian” traditions to modern-day Kazakhstan, where they can still be observed at festivals across the country, such as the Nauryz festival that celebrates the coming of spring.

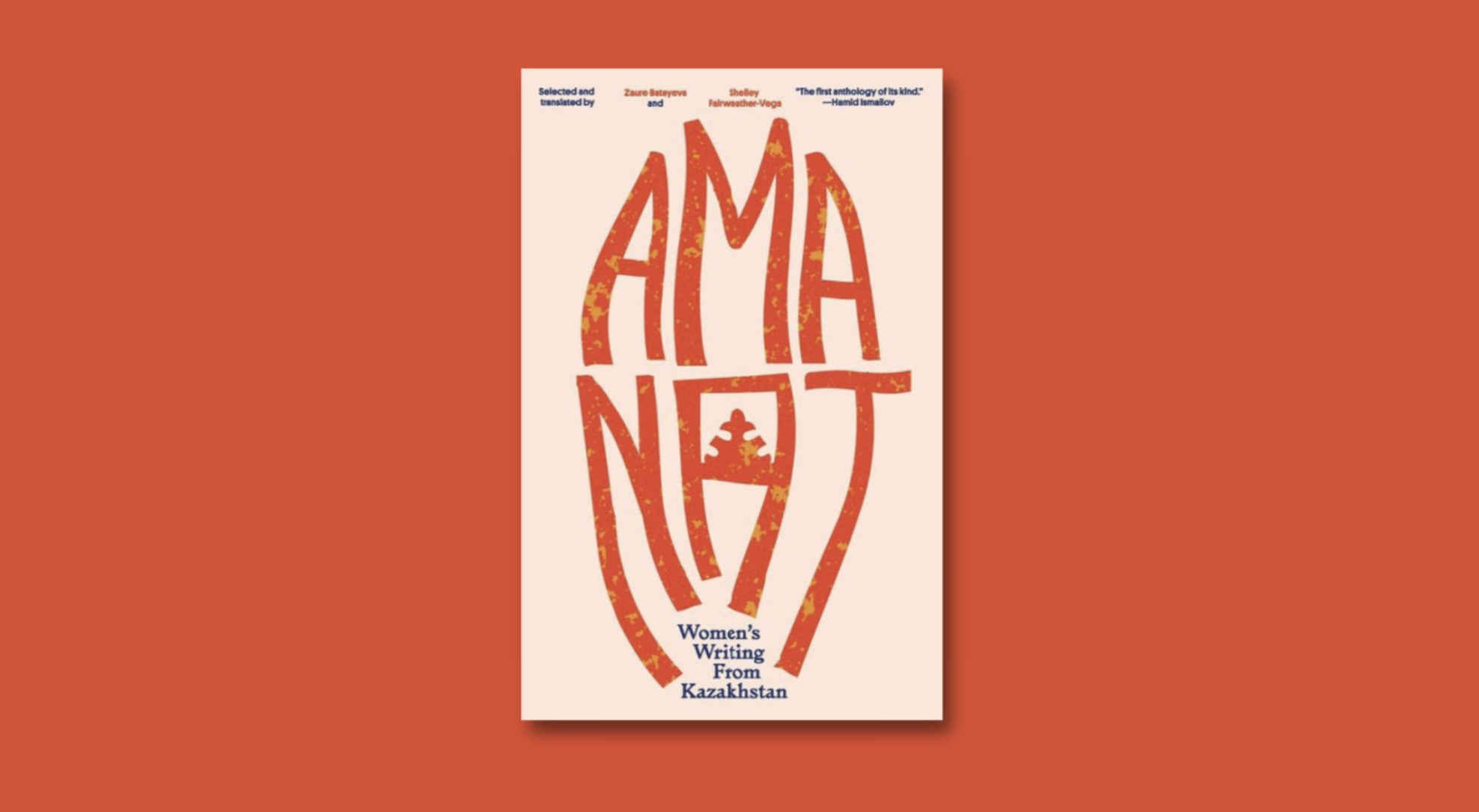

All this was going through my mind as I read Zira Naurzbayeva’s essay “My Eleusinian Mysteries” in the recently published anthology Amanat: Women’s Writing from Kazakhstan, translated by Zaure Batayeva and Shelley Fairweather-Vega. This profound essay dissects, celebrates, and reaffirms the role of women in Kazakh culture, even as it probes the larger questions of existence. In it, Naurzbayeva takes us with her on a nighttime journey across the steppe, the endless sea of grass that is the heart of Kazakhstan:

The trail of light formed by the headlamps of cars racing across the steppe highway dwindled to nothing in the darkness. That light was powerless to illuminate the darkness around us, but nevertheless, there it was. I felt it was not just lighting our journey. The very road in front of the car seemed to appear out of nothing under the rays of light, and then dissolve, disappear in the darkness behind us. My little girl was sleeping on my lap, my traveling companions were sleeping, too…. I alone could recognize this darkness as a wordless, eternal threat to the life flickering warm inside the car.

Here, the physical situation and setting—speeding through darkness in the enclosed womb of the car, daughter asleep against her mother—reenacts the protective, life-giving role of women down through the ages. This central role of women is all the more starkly evident in the context of the Kazakh nomadic heritage and the precarious nature of such an existence:

Suddenly, I thought about my own mother, now dead, and my mother’s mother and her mother and the thousands of generations of my great-grandmothers on my mother’s side, about their lives, giving birth to their children and feeding them, in a yurt blanketed with snow among the frozen and threatening steppe, or on the road during a migration.

At the nomad festival, as I watched the women archers send their arrows flying through the dazzling blue sky, a pleasant koumiss buzz lighting up my senses, it was hard not to feel that the nomadic way of life got a lot of things right. As the Uzbek novelist Hamid Ismailov writes in his blurb for the Amanat anthology, “Turkic languages, including Kazakh, do not have a gender. The nomadic past treated everyone on horseback equally, and therefore the role of women in the history of these peoples was no less than the role of men.”

True, but as Naurzbayeva knows, there is no future without women. Her essay closes on a guardedly hopeful note:

In the car racing across the nighttime steppe, I thought about how my own daughter would take the cup of life from me, the one our grandmothers had carried through the darkness of millennia, through war and hunger, through victory and defeat. And I also felt that we were not alone in the night, that our foremothers were there, invisible, protecting us.

This vision of the spirits of foremothers inhabiting the night could also serve as a fitting epigraph for this pioneering anthology of women writers from a part of the world where their voices have been silenced for too long.

*

The publication of Amanat: Women’s Writing from Kazakhstan represents a watershed moment in the wider appreciation and diffusion of Central Asian literature. Freedom is a hard thing to come by these days in Tajikistan or Uzbekistan, and is utterly impossible in the police state of Turkmenistan. But in Kazakhstan, at least creative writers (if not journalists) have relative freedom. They also often enjoy generous state support—so long as they are men. A recent state-sponsored anthology of contemporary Kazakh prose—translated into six languages and distributed around the world—included only two women among its 30 authors. The Amanat anthology is, in a sense, a response to that slight.

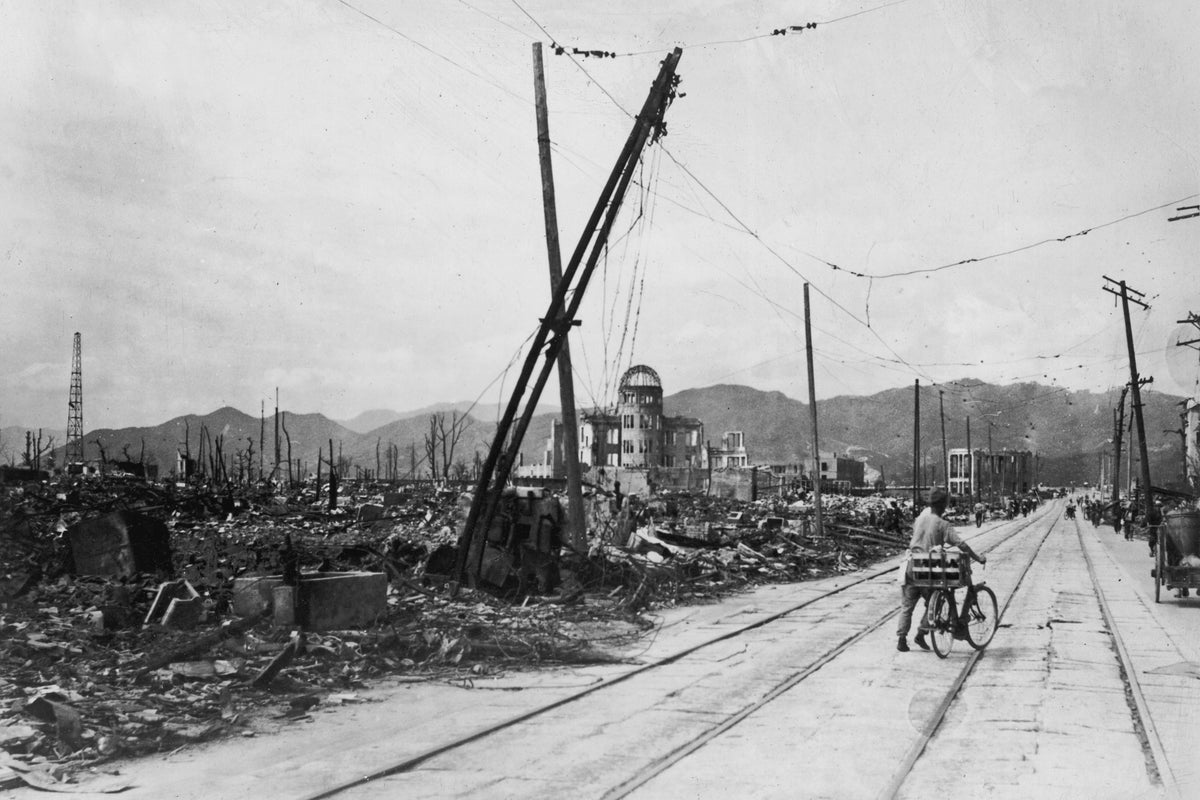

For most of the twentieth century, Kazakhstan was closed off from the world. All of Soviet Central Asia, in fact, virtually disappeared from the global stage. It was largely a forbidden zone where insidious programs of Russification and collectivization sought to erase indigenous languages and cultures, partly succeeding through manufactured famines, widespread executions, and endless deportations. In Kazakhstan, millions died and, with them, a large part of its cultural heritage.

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union and Kazakhstan’s independence in 1991, the resurgence of Kazakh culture and language has been astounding. Everywhere you go, ancient Kazakh symbols abound, stylized snow leopards and winged horses on the currency, on shop signs and tee shirts—the same images of snow leopards and winged horses you can see on Scythian artifacts and ancient stone petroglyphs. The names of cities, streets, and rivers have been changed from Russian back to their original Kazakh. But this resurgence of ancient Kazakh culture has been tempered—and perhaps deepened—by the trials and tribulations of the twentieth century. Kazakhstan today is home to great cities and vast oil and mineral wealth. The population is multiethnic and multilingual, thanks in part to Stalin’s nefarious practice of displacing various ethnic groups to far-flung corners of the Soviet Union. Today, Kazakhstan’s nomadic past survives mostly in cultural beliefs and at festivals, not in practice (though 100,000 Kazakh nomads still live in western Mongolia, having fled from Stalin’s campaign of terror).

This complex history is reflected in virtually all the stories and essays collected in the Amanat anthology. Most are set in the years just before or shortly after the collapse of the Soviet Union and highlight the trials and tribulations of a society attempting to find its way while so many of its key institutions were disintegrating. Many stories focus on the displacement of older people from the countryside to the alien world of the city, specifically women and mothers, since so many of the men have been killed in the “Great Patriotic War” or have been imprisoned, executed, or sent to Siberia. These displaced women and grandmothers do not know how to cope with the “strange city of stone” of the urban environment. As the narrator of Aigul Kemelbayeva’s story “Hunger” complains, “To admire a city is a strange and inappropriate thing for a Kazakh nomad like me. The multiplication of meaningless items in such a big, settled place makes the world too crowded.”

Like many postcolonial countries, Kazakhstan has had to wrestle with the question of language. Many Kazakhstani citizens grew up speaking Russian and were educated in Russian-language schools. Others, particularly those from rural areas, grew up speaking Kazakh as their first language. Of the 24 selections in the Amanat anthology, half were originally written in Kazakh and half in Russian. The translation duties are split between Zaure Batayeva translating from Kazakh and Shelley Fairweather-Vega translating from Russian, both of whom also edited the book and provide a useful introduction.

Most striking about these stories is the sheer exuberance of the storytelling and the tang of the language, which the translators capture so well. There are many gems in the collection, and virtually all these writers will be new to an English-speaking audience.

In Zhumagul Solty’s “Romeo and Juliet,” a retired theater director is asked on short notice to put on a play to impress a visiting delegation of foreigners. The director decides to stage Romeo and Juliet, but can convince only the village elders and retirees to act in it. When the under-rehearsed players forget their lines, they ad lib with Kazakh words “that had nothing to do with the play.” The story’s slow-burn pacing and unexpected twist are worthy of a Shakespearean comedy, though filtered through a uniquely Kazakh worldview. Solty’s other story in the anthology, “An Awkward Conversation,” couldn’t be more different—a tragic tale that manages to capture a family’s entire history during a brief conversation between two friends.

Nadezhda Chernova’s startlingly original story “Aslan’s Bride” is set in a small village on the Caspian Sea in western Kazakhstan. The story has a plot that might have come from Edgar Allan Poe, told with the subtlety and nuance of Chekhov, but every line is suffused with a distinctly Kazakh sensibility that draws the reader in. The unlikely combination of a parched, desert-gothic vibe with a lyrical, poetic yearning gives the story a compelling immediacy. There is a strange reciprocity between the characters and the landscape so that the natural world is perceived as fully alive, brimming with intention and personality:

Milochka tossed off her dress and splashed into the warm water at the shore. The sea recognized her, tossing curved waves to meet her. Milochka squealed and hopped away from the chasing foam, but the waves chased her, grabbed her salt-whitened heels, splattered her face and bare chest with spray. Milochka yelped and covered herself with her hands, laughing out loud. Then she and the sea got tired.

With its unexpected plot twists and poetic subtlety, “Aslan’s Bride” stays with you long after reading it, the aftertaste simultaneously horrific and uplifting.

Zira Naurzbayeva’s story “The Rival” is a closely observed domestic drama that centers on music and the dombyra, the ancient two-stringed, lute-like instrument that has become a national symbol of Kazakhstan. Music, specifically music for the dombyra, suffuses Kazakh culture. Instrumental compositions called kuys are passed down from generation to generation, preserving cultural history and archetypes. In “The Rival,” the husband’s dombyra is described and perceived as a being fully alive, imbued with senses and moods, fully conscious and capable of strong feelings. The musician’s wife comes to regard the dombyra affectionately as her toqal, or junior wife.

Many of these stories and essays, like “The Rival,” provide windows on aspects of Kazakh culture that are usually hidden, and the editors have skillfully sequenced the selections so that they build on each other incrementally. In Naurzbayeva’s essay, “The Beskempir,” for instance, the central, almost shamanic role of grandmothers and woman elders in Kazakh society comes vividly to life, which in turn informs many of the other pieces in the anthology, such as Asel Omar’s “Black Snow of December” or Lilya Kalaus’s offbeat “Operatic Drama.”

In Oral Arukenova’s story, “Amanat” (which also gives the anthology its title), a dying mother voices a deathbed wish to her eldest son to see that her youngest son settles down and marries “a nice Kazakh girl.” This story comes directly after “The Beskempir” and “The Rival,” so that Naurzbayeva’s two pieces can act as a lens through which the deeper significance of Arukenova’s story is revealed. The abrupt conclusion of the story—where the recalcitrant younger brother is seen playing the dombyra—is rife with ambiguity, putting into question exactly which of the brothers is being true to their culture. American readers would likely miss this completely without Naurzbayeva’s preceding two pieces. There are many other highlights in the anthology, from Asel Omar’s incisive “The French Beret” to Olga Mark’s “The Lighter,” about a young prostitute and her companions set loose in the city, to Ayagul Mantay’s evocative “Orphan.”

While this cornucopia of women’s writing is certainly something to celebrate, it does not obscure the fact that women writers in Kazakhstan still face major obstacles, both institutional and societal. In film, fashion, music, and art, women have played a key role in the contemporary resurgence of the arts in Kazakhstan—but in the literary sphere, this is only beginning to become clear as new independent voices assert themselves and find their way into print. Aigerim Tazhi, a brilliant young Kazakh poet, was recently featured at the Rotterdam Poetry International Festival, but this came only after her poems were translated into English in her widely praised 2019 collection, Paper-Thin Skin. Oddly, acclaim often comes from overseas before any significant recognition at home.

*

During another trip to Kazakhstan, I drove south from Almaty with my friend Akmaral toward the majestic snowcapped Tien Shan Mountains (the “Celestial Mountains”) while we discussed the predicament of women artists in Kazakhstan today. Akmaral is an internationally known composer and singer, but she struggles to make a living in Kazakhstan, where people regularly pirate her music or fail to pay for commissioned compositions. “It is a society of thieves. There is nothing you can do,” she says. “People steal my music all the time. I complain, ask them to stop, but nothing is done.”

When we got to Shymbulak, the famed mountain and ski resort, we took the funicular up three stages to about 10,000 feet, then hoisted our backpacks and began climbing higher. It was a sweltering summer day in Almaty, but as we hiked up past the snowline, the air was bracingly cold, and we had to add extra layers of clothing. “Sometimes I am hired to compose things, but then I am given no credit,” Akmaral muses. “Someday perhaps I will move to America.”

Akmaral is divorced with a young son. Her performing name is Mergen, which in Kazakh literally means “the shooter” or “archer,” but when applied to a woman has connotations of “woman warrior.” I first became aware of Mergen when I saw the video for her song “Tolqyn” from her album TYH, which means “night” in Kazakh. In the video, Akmaral is seductive, powerful, and more than a bit menacing. Then I happened on her album Qazaq Lounge, where she uses ancient Kazakh instruments to play traditional songs but with a hip, modern vibe. I got in touch with her to tell her how much I admired her music, and eventually we became close friends.

In person, Akmaral seems about half the size of her stage persona, easygoing, dressed in blue jeans. Lately, she has been spending most of her time composing scores for movies, such as The Horse Thieves: Roads of Time, while also starring in the lead role in Zhannat Alshanova’s movie The History of Civilization, which won a silver medal at the Locarno Film Festival. I joke with her that she is the Kazakh Lady Gaga. Akmaral shrugs this off. “Hardly anyone in Kazakhstan listens to my music. They say it is too crazy,” she says. “Only people in Europe or far away know who I am. In my own country, I am no one.” She was exaggerating, but only a little. Plenty of people in Kazakhstan know of her, but her major awards have come from places like Germany, Switzerland, and Ukraine.

As we paused in our climb, now well past the snowline, I looked around at the snowcapped peaks all around us. It was as if we’d passed into Shangri-La. Back in the thirteenth century, this vast area of the Tien Shan was ruled by Qaidu Khan and his celebrated daughter Khutulun. Khutulun was a renowned wrestler and a warrior famous for her exploits in battle. The story goes that Khutulun would only marry a man who could defeat her in wrestling. Scores of men tried and failed, and her fame grew. Khutulun’s story filtered into western literature in various retellings and embellished tales, eventually serving as the basis for Puccini’s Turandot. And here I was now, climbing with Mergen, a woman warrior in the field of contemporary music. I imagined that Puccini would have been impressed as well as Khutulun.

When we got back to the city, all of Almaty was abuzz about the release of the new film Tomyris. All over Kazakhstan, Tomyris is revered as a national hero, a warrior queen who defeated the invading Persian army in 530 BCE, personally beheading the Persian king. There were posters everywhere, families with kids thronging the theatre. When we inquired about tickets, we were informed that all shows were sold out. So the admiration, even veneration, of strong women lives on in Kazakhstan even if contemporary social structures and the webs of patriarchal nepotism tend to thwart them at every turn. The Amanat anthology represents a big step ahead in this regard.

*

Back at that nomad festival, just as my friend and I were leaving, we browsed the many booths of traditional craftspeople offering tooled leather saddles, traditional musical instruments, and handcrafted jewelry. An exquisite silver amulet caught my eye. It was triangular with delicate silver pendants dangling from the bottom. It was exactly like the ancient amulet described by Sheila Paine in The Afghan Amulet. Paine traced this primordial triangular amulet on a years-long quest across Central Asia and beyond—from Afghanistan to Kyrgyzstan, the Himalayas to Bulgaria—seeking out its homeland. And now here it was, plain as day, fashioned by an octogenarian Kazakh silversmith with whom I bartered with gestures and hand signals. For millennia, across diverse cultures and religions, this triangular amulet symbolized female fertility, and was likely related to ancient images of the mother goddess.

As we left the festival, silver amulet safe in my pocket, the scores of cars parked helter-skelter on the grass could not dispel the notion that ancient traditions had indeed survived in Kazakhstan despite overwhelming odds. And it is this admixture of an age-old traditional culture with a modern, technologically savvy population that has come to define the new Kazakhstan after 30 years of independence.

Amanat is a Kazakh word with many meanings. As the editors explain, an amanat “is a promise entwined with hope for the future. It is frequently a task that comes with moral obligation, and often it is a legacy, an item of value, handed down for us to cherish and protect.”An amanat can be a deathbed vow, a sacred trust—or it can be an anthology dedicated to a cause and bequeathed to the future. Like that silver amulet, the Amanat anthology has something magical and hopeful about it. That amulet now hangs on the wall by my desk, the anthology directly below it. That seems fitting.