In one episode of the reality show Life After Death with Tyler Henry, which follows the titular clairvoyant medium as he travels the U.S., Henry quips “I think gay men are destined to like Mariah. The hormones that make you gay in the womb, I think she’s responsible.” Henry, who is gay and doesn’t particularly care for Carey’s voice, admits he is nevertheless drawn to her on account of some “gay requirement.”

A Carey fan myself, at first I wasn’t exactly sure what Henry meant by this, but I have a clearer picture now for having read Andrew Chan‘s Why Mariah Carey Matters. Chan’s slim volume covers not only Carey’s artistry, but also the sociological aspects of her celebrity, and—more nebulously—why and how she became a towering gay icon. These ideas often overlap and complicate each other. Indeed Carey is more than just a famous singer; her omnipresence reaches far beyond her discography, and somewhere down the line she morphed into her own sort of sensibility—a byword, and an especially divisive one.

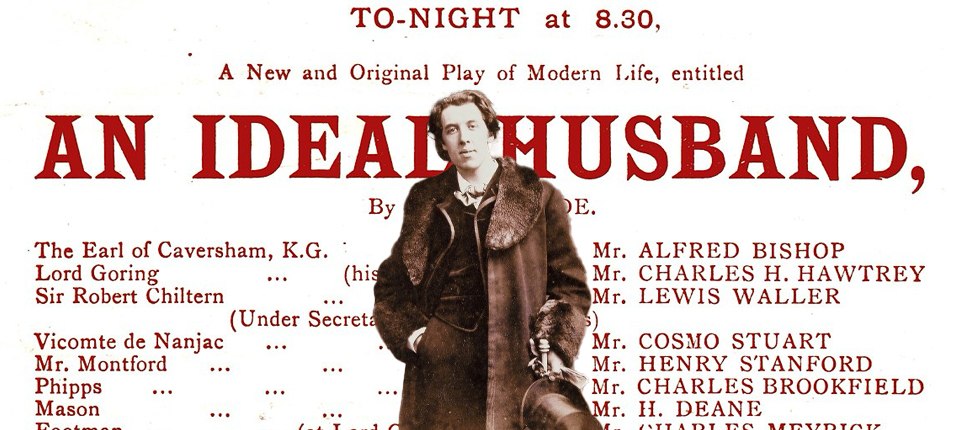

Carey, who has become an oft-memed camp icon, embodies the slippery nature which Sontag, in Notes on Camp, called “gestures full of duplicity, with a witty meaning for the cognoscenti and another, more impersonal, for the outsider.” Two of Carey’s favorite qualifiers are “true” and “real,” as in “only my true fans understand” or “the real lambs know.” (“Lambs” are what Carey’s most ardent fans call themselves; as a group, “the Lambily.”) Her output is filled with Easter eggs to reward insiders, and over the past 33 years her personal iconography has accrued such density as to make the fluent feel like experts. Yet outside the Lambily, Carey draws mixed reactions. Some deride her as the washed-up Queen of Christmas, while others recall her nostalgically as the singer of bubbly throwbacks. A few even praise her as a pioneering biracial woman in entertainment. Detractors are easy to find, as is a general indifference toward Carey. So her most ardent fans—those chosen few—cling to one another with near-religious zeal.

Carey, who has become an oft-memed camp icon, embodies the slippery nature which Sontag, in Notes on Camp, called “gestures full of duplicity, with a witty meaning for the cognoscenti and another, more impersonal, for the outsider.” Two of Carey’s favorite qualifiers are “true” and “real,” as in “only my true fans understand” or “the real lambs know.” (“Lambs” are what Carey’s most ardent fans call themselves; as a group, “the Lambily.”) Her output is filled with Easter eggs to reward insiders, and over the past 33 years her personal iconography has accrued such density as to make the fluent feel like experts. Yet outside the Lambily, Carey draws mixed reactions. Some deride her as the washed-up Queen of Christmas, while others recall her nostalgically as the singer of bubbly throwbacks. A few even praise her as a pioneering biracial woman in entertainment. Detractors are easy to find, as is a general indifference toward Carey. So her most ardent fans—those chosen few—cling to one another with near-religious zeal.

Rarely do Lambs randomly encounter one another in the wild. This separateness—the most delicious part of diva worship—is what Sontag means when she writes that “behind the ‘straight’ public sense in which something can be taken, one has found a private zany experience of the thing.” That “private zany experience” reported by so many is precisely the challenge of writing a book about Carey. As Sontag herself disclaims at the beginning of Notes on Camp: “It’s embarrassing to be solemn and treatise-like about camp. One runs the risk of having, oneself, produced a very inferior piece of camp.” Chan largely escapes this fate, striking an elegant balance of tone and writing as a critic, a reporter, and a memoirist all at once. He flexes his journalistic chops to dismantle erroneous narratives about Carey, and when Carey’s effect on audiences poses a phenomenological hurdle, he spins illuminating personal narratives only to then pivot towards rigorous close-readings of her lyrics, voice, and performances worthy of Barthes’s Mythologies. Carey’s association with, in Chan’s words, “the frothy and superficial” makes the argument for her “mattering” an especially audacious one. Establishing Carey’s aesthetic significance, Chan tenderly dissects her artistry, making the case that “singing like hers is creative and intellectual labor.” His analysis of Carey’s magnum opus Butterfly, her sixth studio album released in 1997, aroused in me the same response he attributes to virtuosic singing: “Some of us respond with gestures of ecstasy: closing our eyes, trembling and shuddering, scrunching up our faces, holding our hands up as if to catch the sound in midair.”

Rarely do Lambs randomly encounter one another in the wild. This separateness—the most delicious part of diva worship—is what Sontag means when she writes that “behind the ‘straight’ public sense in which something can be taken, one has found a private zany experience of the thing.” That “private zany experience” reported by so many is precisely the challenge of writing a book about Carey. As Sontag herself disclaims at the beginning of Notes on Camp: “It’s embarrassing to be solemn and treatise-like about camp. One runs the risk of having, oneself, produced a very inferior piece of camp.” Chan largely escapes this fate, striking an elegant balance of tone and writing as a critic, a reporter, and a memoirist all at once. He flexes his journalistic chops to dismantle erroneous narratives about Carey, and when Carey’s effect on audiences poses a phenomenological hurdle, he spins illuminating personal narratives only to then pivot towards rigorous close-readings of her lyrics, voice, and performances worthy of Barthes’s Mythologies. Carey’s association with, in Chan’s words, “the frothy and superficial” makes the argument for her “mattering” an especially audacious one. Establishing Carey’s aesthetic significance, Chan tenderly dissects her artistry, making the case that “singing like hers is creative and intellectual labor.” His analysis of Carey’s magnum opus Butterfly, her sixth studio album released in 1997, aroused in me the same response he attributes to virtuosic singing: “Some of us respond with gestures of ecstasy: closing our eyes, trembling and shuddering, scrunching up our faces, holding our hands up as if to catch the sound in midair.”

Indeed I felt ecstatic upon reading Chan’s description of Butterfly as “an album of decadent beauty and rococo adornments,” just as I did when he dignified Carey’s signature vocal layering as “building out an atmosphere from exquisite filigree and pointillist detail,” or best of all, when he labels her horniest song, “The Roof,” as “carnal,” “menacing,” and a “Proustian memento” Though he dutifully cites Carey’s impact on a generation of singer-songwriters; the import of her genre forays into hip-hop, house, and gospel; and the ignorant racializations hurled at her since her debut, Chan intuits something more essential about Carey. Why exactly does a certain subset of the public feel so ardently about Carey? Even with her virtuosic abilities, and her early commercial dominance, Carey would not have become the icon (in the most literal sense of the word) if not for that inexplicable devotion—would not have acquired the almost hagiographic reverence usually reserved for artists of her stature who have already died.

According to Chan the answer lies, ironically, not in her more accomplished output but in the juxtaposition between her agonizing introspection and her shallower incarnations. Chan cites his adolescent disenchantment with Carey, how he detested her 1999 album Rainbow upon its release, grew embarrassed by his love for Carey, and opted instead for the alternative fare of the ‘90s. He recalls a conversation with a gay elder on an early-aughts message board who expanded his sense of what matters:

According to Chan the answer lies, ironically, not in her more accomplished output but in the juxtaposition between her agonizing introspection and her shallower incarnations. Chan cites his adolescent disenchantment with Carey, how he detested her 1999 album Rainbow upon its release, grew embarrassed by his love for Carey, and opted instead for the alternative fare of the ‘90s. He recalls a conversation with a gay elder on an early-aughts message board who expanded his sense of what matters:

In retrospect, I like to think that my pen pal was teaching me, in his own indirect way, that escapism is key to any great Diva’s relationship with her queer fans—and that, ultimately, the fear of what’s being escaped is never all that far from view.

Carey’s insistence on being both profound and frivolous, on being serious while exaggerating her unseriousness, is the secret language—the “witty meaning for the cognoscenti”—of sexual minorities everywhere who by virtue of being a joke assert that they are in on it. But this survival mechanism does not come without cost. It dooms one to forever be split between the “straight” and the “zany,” to adapt one’s presentation in response to the audience’s prejudice; to code-switch, to come out of the closet over and over again. As Chan puts it while discussing Carey’s role in the 2001 movie Glitter:

Carey’s insistence on being both profound and frivolous, on being serious while exaggerating her unseriousness, is the secret language—the “witty meaning for the cognoscenti”—of sexual minorities everywhere who by virtue of being a joke assert that they are in on it. But this survival mechanism does not come without cost. It dooms one to forever be split between the “straight” and the “zany,” to adapt one’s presentation in response to the audience’s prejudice; to code-switch, to come out of the closet over and over again. As Chan puts it while discussing Carey’s role in the 2001 movie Glitter:

That Mariah decided to name her big screen debut—a film that so obviously draws inspiration from her own life—after this symbol of artifice, excess, marginality, and non-respectability shows us something she shares with many of her queer fans: her pain is forever bound up with the performative strategies with which she’s learned to transmute it.

And there is the paradox, the duplicity. Though I myself lust for Carey’s vindication, I love her precisely because she has been willfully misunderstood, and because she has improvised ways to thrive in the face of derision. Chan notes the beleaguered dilemma vital to Carey-worship:

As long as a sizable swath of the population goes on thinking of her as a capricious, undisciplined diva—the remnant of a bygone era of superstardom, resting on her laurels—the lambs can look to the depth and wit of her best music as a secret, a treasure waiting to be uncovered by anyone willing to give her work a closer listen.

Carey notoriously refers to herself as the “elusive chanteuse,” and that tagline certainly applies. But after reading Why Mariah Carey Matters, I will think of her more as a duplicitous diva—my private zany experience, my secret knowledge. The woman who understands what it is to keep going despite knowing that she will never be fully understood, or in her own words: “Ambiguous / Without a sense of belonging to touch / Somewhere half-way / Feeling there’s no one completely the same.”