Thirty years ago, I left for a semester abroad in Siena, Italy—a decision that, were my life a novel, I might call the “inciting incident.” Once I arrived, I resolved to truly immerse myself in the culture, and being fluent in Italian became an obsession—a lonely one, since I often forced myself to forfeit outings with other Americans so I could instead practice Italian. I’d struggled to learn the language in my freshman year of college, but once in Italy, nothing short of fluency would satisfy me.

One of the first words I learned on the ground in Italy was the verb scherzare. It means “to joke” and is indispensable for following almost any conversation with Italians. During a trip I took to Sicily, a Palermo policeman warned me about strange men near the station by yanking on the skin below his eye with his finger, and uttering a single word, occhio, which simply means “eye.” I was hooked.

Mastering Italian gave me a sense of accomplishment, something I rarely felt at my college, where I was in over my head among the boarding school grads and future Manhattan literati. And when I couldn’t be in Italy, this passion found an outlet in books. Reading Italian literature submerged me into a kind of intoxication—an explosion of sound and thought, because as well as I know the language, Italian sounds still delight and sometimes even confound me. I discovered authors like Natalia Ginzburg and later Elena Ferrante, and rediscovered titans like Dante and Petrarch, who allow me through their works to unravel—or at least revel in—the mysteries of Italy in Italian. In an essay from the anthology Lives in Translation, the writer Ariel Dorfman cites the “incessant and often perverse doubleness” of being fluent in two languages. Italian is like a twin who accompanies me everywhere—for better or for worse. When I was a student, and later an expat, living in Italy and speaking Italian simultaneously enchanted and befuddled me. I longed for something different but sometimes recoiled at how that difference isolated me: all those lonely walks in Siena hoping someone would talk to me in Italian; wishing as I heard the tell-tale clatter of forks and knives filtering out of the windows that someone would call down to me with an invitation to a meal.

Mastering Italian gave me a sense of accomplishment, something I rarely felt at my college, where I was in over my head among the boarding school grads and future Manhattan literati. And when I couldn’t be in Italy, this passion found an outlet in books. Reading Italian literature submerged me into a kind of intoxication—an explosion of sound and thought, because as well as I know the language, Italian sounds still delight and sometimes even confound me. I discovered authors like Natalia Ginzburg and later Elena Ferrante, and rediscovered titans like Dante and Petrarch, who allow me through their works to unravel—or at least revel in—the mysteries of Italy in Italian. In an essay from the anthology Lives in Translation, the writer Ariel Dorfman cites the “incessant and often perverse doubleness” of being fluent in two languages. Italian is like a twin who accompanies me everywhere—for better or for worse. When I was a student, and later an expat, living in Italy and speaking Italian simultaneously enchanted and befuddled me. I longed for something different but sometimes recoiled at how that difference isolated me: all those lonely walks in Siena hoping someone would talk to me in Italian; wishing as I heard the tell-tale clatter of forks and knives filtering out of the windows that someone would call down to me with an invitation to a meal.

Literature to the rescue. The first words from Italian literature to truly cast a spell over me were about a dark wood: Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita, mi ritrovai per una selva oscura, ché la diritta via era smarrita. They are the opening words of Dante’s La Divina Commedia, and in English, they mean: “Midway through our life’s journey, I found myself in a dark wood as the true path had been lost.”

Literature to the rescue. The first words from Italian literature to truly cast a spell over me were about a dark wood: Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita, mi ritrovai per una selva oscura, ché la diritta via era smarrita. They are the opening words of Dante’s La Divina Commedia, and in English, they mean: “Midway through our life’s journey, I found myself in a dark wood as the true path had been lost.”

Unlike many other passages from this 14th century masterpiece, I understood all of the words. OK, I thought, game on. I’d found the door to a new universe, and I was desperate to go inside. I dare say Jhumpa Lahiri felt the same way; in her book, In Other Words, she describes reading in Italian as “almost miraculous” and “more demanding, yet more satisfying” than English.

Unlike many other passages from this 14th century masterpiece, I understood all of the words. OK, I thought, game on. I’d found the door to a new universe, and I was desperate to go inside. I dare say Jhumpa Lahiri felt the same way; in her book, In Other Words, she describes reading in Italian as “almost miraculous” and “more demanding, yet more satisfying” than English.

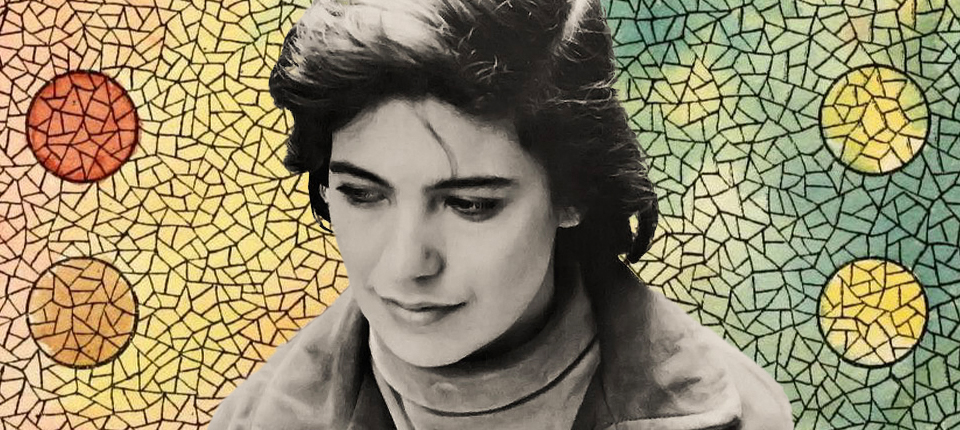

Even the minutest linguistic quirks thrill me, and as such I fell in love with Lessico Famigliare by Natalia Ginzburg (translated by Jenny McPhee under the title Family Lexicon in 2017). Recalling conversations shared over the dinner table with her parents and her siblings, Ginzburg cites specific words from a family patois; her father, for example, used the word sempiezzi, derived from the word for simple (semplice), to describe anything silly.

It’s one of many delightful words cited but I adore even basic Italian constructions that differ from English. She writes that her father “dava dello stupido a tutti.” To approach it as David Sedaris might have in his hilarious memoir about learning French, Me Talk Pretty One Day, it means literally: ‘He gave of the stupid to all.’ McPhee properly translates it this way: “He […] thought everyone was stupid.” But the Italians use the verb “to give,” and the way this construction conveys a sense of special handling, or a label, mesmerizes me.

It’s one of many delightful words cited but I adore even basic Italian constructions that differ from English. She writes that her father “dava dello stupido a tutti.” To approach it as David Sedaris might have in his hilarious memoir about learning French, Me Talk Pretty One Day, it means literally: ‘He gave of the stupid to all.’ McPhee properly translates it this way: “He […] thought everyone was stupid.” But the Italians use the verb “to give,” and the way this construction conveys a sense of special handling, or a label, mesmerizes me.

In Ginzburg’s dialogue, there’s an element of Italian conversation that I love: repetition. She quotes her mother as saying, “Come mi piace a me il formaggio.” McPhee deftly renders the phrase as, “How I do love cheese.” Italians, however, express like or dislike—even in their most intense forms—passively, akin to how we use the verb “to please.” So what Ginzburg’s mother says literally is: Oh how cheese is pleasing to me. But in a twist, she repeats ‘me.’ Literally: Oh how cheese is pleasing to me—to me. This phrase is sometimes slangily (and ungrammatically) constructed by putting the extra “me” first: “A me mi piace il formaggio.” There is a bit of Italian logic here. The phrase, “A me mi,” which I often heard in Tuscany, slides off the tongue. The opposite of a contraction, it adds a sound. And inserting that extra sound makes the phrase liscio, smooth.

Then there’s “la Paola,” Ginzburg’s term for her sister. It literally means “the Paola.” It’s not arcane but it always delights me since I hear it as though it were an honorary and perhaps humorous title. Ginzburg writes, “La Paola era […] gelosa delle amiche di mia madre.” Paola was jealous of my mother’s friends, reads McPhee’s translation. Why am I besotted with the appellative “la Paola”? Unfamiliarity, perhaps, breeds enchantment. To my ears, it sounds almost formal, like Her Excellency, but it also suggests (to me and maybe me alone) an inside joke like, “Nudge, nudge, wink, wink, that Paola.”

*

In Elena Ferrante’s The Lost Daughter, the narrator admits, “Le lingue per me hanno un veleno segreto.” That means: Languages contain a secret poison for me. The novel is about a woman haunted by her early days of motherhood. In the same paragraph, Ferrante describes the protagonist’s mother as “intossicata dallo scontento.” Translator Ann Goldstein renders it as “poisoned by unhappiness.” Intossicata dallo scontento. Reading it, I repeat the phrase again and again, losing myself in the soft s of intossicata.

In Elena Ferrante’s The Lost Daughter, the narrator admits, “Le lingue per me hanno un veleno segreto.” That means: Languages contain a secret poison for me. The novel is about a woman haunted by her early days of motherhood. In the same paragraph, Ferrante describes the protagonist’s mother as “intossicata dallo scontento.” Translator Ann Goldstein renders it as “poisoned by unhappiness.” Intossicata dallo scontento. Reading it, I repeat the phrase again and again, losing myself in the soft s of intossicata.

Poisoned by unhappiness is also a good description of Olga, the protagonist of Ferrante’s The Days of Abandonment, a devastating novel about the breakup of a marriage after the husband’s infidelity. In one chilling moment, Olga encounters Mario and his new paramour, Carla (the former babysitter), on the streets of Torino. Realizing how long she’d been fooled, Olga becomes unhinged. She rips off Mario’s shirt then lunges at Carla, grabbing at her earrings—a family heirloom of Mario’s that Olga once prized. “I wanted to rip them from her lobes, tear the flesh, deny her the role of heir of my husband’s forebears,” reads the Goldstein translation.

Poisoned by unhappiness is also a good description of Olga, the protagonist of Ferrante’s The Days of Abandonment, a devastating novel about the breakup of a marriage after the husband’s infidelity. In one chilling moment, Olga encounters Mario and his new paramour, Carla (the former babysitter), on the streets of Torino. Realizing how long she’d been fooled, Olga becomes unhinged. She rips off Mario’s shirt then lunges at Carla, grabbing at her earrings—a family heirloom of Mario’s that Olga once prized. “I wanted to rip them from her lobes, tear the flesh, deny her the role of heir of my husband’s forebears,” reads the Goldstein translation.

In Italian, Ferrante describes Olga’s attacks on the lovers with the verb strappare, a word she uses five times in three pages. It means “to rip,” but also conveys a sense of snatching, of grabbing violently. Even just saying the word, you feel as though your teeth are shredding something. Fitting, since Ferrante describes Olga’s state of mind while assaulting them as a “black frenzy of destruction.”

Strappare begins with a trio of letters familiar to English speakers. In Italian, this combination of consonants is pronounced by stretching the mouths wide and striking the tongue forcefully behind the front teeth. ‘The word also contains a doppio: the doubling of consonants which is one of Italian’s distinctive sounds. It requires the speaker to linger for a moment on the consonant’s sound in order to fully and audibly emphasize it. Italian demands precision, and early on, I began to see speaking Italian well as a kind of command performance. There’s no phoning it in.

It was a hard lesson to learn. In my years in Florence, I lived and died by whether an Italian mistook me for a native speaker. It was not unlike trying to break into a hostile high school clique that hazes you until it finally accepts you. By the time you’re “in,” you are meant to overlook that these were the people torturing you—in the case of Italy because you said capelli (“hair”) when you meant to say cappelli (“hats”). But some part of me never forgot the years of rejections and corrections.

For me, this complex attachment to Italy—and Italian—is crystallized by a line from Ferrante’s Frantumaglia in which she says the books she’s managed to publish are those that “put fingers in particular wounds of mine that were still infected.” Wounds of mine that were still infected. I underlined the sentence, then bracketed the paragraph. I found myself returning to those words, in the original Italian: ferite (“wounds”) ancora (“still”) infette (“infected”).

For me, this complex attachment to Italy—and Italian—is crystallized by a line from Ferrante’s Frantumaglia in which she says the books she’s managed to publish are those that “put fingers in particular wounds of mine that were still infected.” Wounds of mine that were still infected. I underlined the sentence, then bracketed the paragraph. I found myself returning to those words, in the original Italian: ferite (“wounds”) ancora (“still”) infette (“infected”).

For many reasons, I wasn’t able to live in Italy full-time forever, something I grieved over for years—a wound of mine that was still infected. It led me at times to conclude that Italy had ruined my life because I’ve been tethered to it for decades, often failing to make the most of my time “here” because I am wishing to be “there”—where I can speak Italian. As Lahiri wrote in her diary shortly before her own departure from Italy, “I think about the distance that will exist between me and this place, and I fall into a depression.” Lahiri’s depression would be in the same medical category as mine: lack of Italian to the ears.

I consider my time in Italy to be the most momentous period of my life, largely because of sound. The sound of Italian. Once I could think in two languages, there was no going back to an English-only life. Over the years, I’ve often thought about an expression my father said when I was younger: “You can’t go home again.” He repeated it to me when I insisted on returning to Italy after my college graduation. It was Ferrantesque in its ability to hem me in, and convince me my Italian life was over. Luckily, I finally concluded that knowing a foreign language confers a special kind of passport. I can’t go home again? Sure I can. So long as I can speak and hear and read Italian, I’m home.