In my second year of college I applied for a spot in a creative writing program. If I got in, I could graduate in two years with a writing major. If I didn’t, well, I needed a new major. I fussed over the application for months. Attended info sessions, met with the program director, revised my portfolio of poems so often that one professor finally said, Bryan, relax. Let the poems speak.

I didn’t grow up saying I wanted to be a writer, but the signs were there, like a secret wish I kept from everyone, myself included. A stroll through the half-hearted journals and failed diaries of my teenage years turns up observations like: “I want to write books, but you can’t make a living that way.” Such a Midwesterner: The arts just aren’t practical.

Then one cold October afternoon my parents came to visit campus and I stumbled through a confession of sorts: I want to be a poet, I said. I want to declare a major in poetry. To their credit, they took the news quite well. My mom, who captained the family finances, asked a familiar question: How does a poet make a living, exactly?

I got the good news on a Tuesday afternoon. I don’t know how many other people applied, but I felt like one of God’s own elect. I met with Mary Kinzie, the poet who ran the writing division. Her office had books piled on the desk and floor. Propped behind a chair in the corner was the promotional poster for a reading she gave at Barnes & Noble for Ghost Ship, her most recent book published by Knopf. Knopf! I can’t recall a word she said that day, just the halo of high hopes that encircled our conversation.

The practice of my college was to preface each quarter with a reading week, prep time with no in-person classes. Professor Kinzie sent a list of poems for apprentice poets to read. A very long list. You began at the dawn of English poetry: Chaucer, Wyatt, Spenser. Then, you made a go of Marlowe, Cowper, and Marvell. The names rolled on for pages; I hadn’t known there were so many worthy poets. Sometimes their lines were melodic. Sometimes they were arcane. Sometimes they put me to sleep.

Ahead of the first class, I received the following email: “On September 27 you will bring the Norton anthology, your reader, and the supplemental volumes to class. An 80 minute exam will cover ideas about prosody and mode in concept AND as they apply to poems. Be prepared to differentiate the practice of 17th, 18th, and 19th century poets with respect both to mode and prosodic habits.”

In the seminar room on day one I met 11 other very anxious apprentice poets. Based on small talk and a few sotto voce confessions, I estimated that basically all of us had either skimmed or failed to finish large swaths of the reading. I don’t even know if I like poetry anymore, one person confessed.

For reasons I can’t recall, we took the exam at home rather than completing it in class. Together, we reviewed the syllabus. We would be reading and writing sonnets, sestinas, georgics, odes, blank verse and, then, using a form of our choice, we would compose a long poem of 150 lines or longer. This is a program for serious poets, Professor Kinzie said. I’ll treat you as such. One of the other apprentice poets meekly asked if we’d ever write free verse poems. You’d think she asked if poems could be submitted in pig Latin.

A deep understanding of prosody is crucial for poets, Professor Kinzie said, before you write in free verse. She spoke those last two words as if she were describing a clot in a sewer trap. In the briefest of space she conveyed the totality of her disdain for unstructured expression. She was, you see, a most formidable poet.

Over the following weeks we wrote imitation poems, drilled on prosody, attempted (and flubbed) critical readings. Poets of some renown came through for Q&As and master classes; two past and future U.S. poet laureates, Robert Pinsky and Donald Justice gave remarks, then vanished like brief pale fire. In workshops we read and remarked on each other’s poems, debating what worked, what didn’t, if a piece broke any rules of form, what other poems a student’s poem reminded us of.

What makes a poet a poet? There is of course no simple answer. You could argue that self-declaration is enough. You could also argue there must be a measure. Looking back now, decades later, I chuckle at how earnestly I believed that to be a real poet I had to earn the approval of an academic gatekeeper. As if a poet were like a doctor or a lawyer, a practitioner whose title is contingent on meeting strict criteria. Certainly, no one awarded John Keats or Percy Shelley a license to practice blank verse.

I don’t know what I thought it would feel like to be a poet apprentice. Certainly, I thought there would be more rhapsody, less scansion. When classmates complained out of school that they wanted more freedom, I nodded along, but inside, like a goody-good student, I thought, well, we have to earn it. I didn’t love the dogma, but I did agree with the underlying philosophy of the apprenticeship: To become a poet one must first take something mystical—being a poet—and break it into specific, tactile, almost quotidian acts. A poet reads poems. A poet knows meter, scans lines, gestures with metaphors. And, most importantly: A poet has a routine, a tool kit, and readiness to work, whenever the time to work hits. Useful truths, no matter what your definition of a poet might be.

There was just one problem for me as an apprentice poet. My analysis lacked verve. My meter was poor. My metaphors were a mixed bag. I earned a pat on the head now and then from Kinzie and the gruff, pony-tailed poet who led the composition of our long poems. But if you set aside ambition, energy, and desire, I wasn’t a great poet. I was adequate, at best.

To reassure my parents that I could one day repay the Stafford loans that underwrote my college education, I also carried the course load for a second major, psychology. Laugh if you will, but compared to poets, psychologists make serious bank. Gradually, this other major was beginning to feel less and less like a backup plan and more like an organized retreat. Q: How do merely adequate poets make a living? A: They don’t.

For a two-week period during winter quarter our group wrote daily poems. Each poem was a response to a prompt. One day’s prompt was to retell the scene from a famous novel. I was at the time reading Frankenstein for another class. For my poem, I reimagined the passage when Victor leaves his new bride Elizabeth on their wedding night. He tells her he must hunt down the monster he created before it can harm her. While he’s gone, the creature sneaks in, kills her. My sonnet depicted the scene from Elizabeth’s point of view. Here is the poem as I wrote it on January 28, 1997:

“Elizabeth Waiting”

How strange the way beloved Victor prowls,

The loaded gun still hanging from his belt,

His eyes all raging forth with fires that melt

A night so haunted that the trees give howls.

The shutter claps, ‘tis rain, just rain to see– 5

He sent me to the bedroom that I might retire.

I know that soon he will be drawn in by the wire

That binds us to our sacred destiny.

I hope that neither distance brought by years,

Nor sorrow always just outside our door, 10

Nor grief have made his passion stark–

Is that a noise? No, just my falling tears–

Victor! Wander far from me no more,

Why do you shun the duties of a patriarch?

Yeah. It’s a standard-issue sonnet, iambic, wobbly on its feet (sometimes five per line, sometimes four), with a so-so volta, an odd usage of stark, and a Petrarchan rhyme scheme, abcabc. Mechanically, it’s flawed, like most of my poems. But spiritually, for me it was a leap forward. It suggested a character, embodied a voice, set a scene. It had a flicker of its own life, albeit via a flame borrowed from Mary Shelley.

I don’t remember what Professor Kinzie said about my sonnet. I think she called out the places where the meter slips. And tsk-tsked the use of archaic diction on line 5. I took it all as valid criticism and set to work on the next daily poem. But for days afterward, I kept thinking about this one, about how much I enjoyed writing it, flaws and all.

Not long after, late on another winter’s night, I went chasing that feeling again. I banged out a short story called “Return to the Masters,” a fable about busy everyday adults who inexplicably begin buying poetry books en masse, pushing poets to the status of pop stars, driving a societal shift no one can explain. It wasn’t great, but it had a good beat, you could dance to it, and— – get this—I loved writing it.

Before I studied under Mary Kinzie, I believed that writing was like waiting for the weather. You could sense when something big was coming, but you couldn’t really say for sure when it would hit, and there was almost nothing you could do to change whether it was a good or bad thing. Near the end of the first year of my apprenticeship, I was a better writer, yes; but I still felt like I had so much to learn. I needed more guidance, more time.

Seeking help, I had coffee with another professor in the writing division, an affable man who wore a bow tie to class and addressed students formally, using last names. His class was called Fundamentals of Prose and on the first page of a piece I wrote for him on the joys of driving, he wrote, “Grade: A. Keep going sir, and never look back.” Did he think, possibly, maybe, sort of, that I wasn’t meant to be a poet? Did he think I should spend more time with essays, fiction?

I finished my obligations as an apprentice, turned in my long poem, and attended the end-of-year celebration with my fellow poets. (Look ma, no modifier!) But I would never again call myself a poet. I had a new appellation in mind: short story writer.

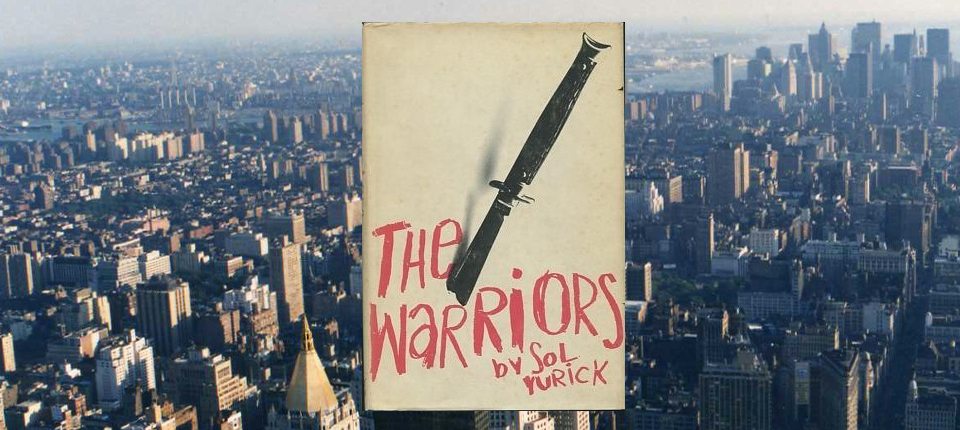

Within weeks, with some help from my prose professor, and the blessing of Professor Kinzie, I enrolled in a second apprenticeship, received a new reading list, this one full of novelists and short story writers. With joy and care I worked my way through local used bookstores in search of books by Kazuo Ishiguro, Alice Munro, Thomas Pynchon. Names I had not heard of before. New worlds I was eager to circumnavigate.

Maybe this is it, I thought. Maybe I’ve found the right place to apply myself. The path was clear, I said to someone at the end-of-year party for apprentice poets. It felt like a hard won truth. Of course, it wasn’t. Anyone who’s labored for long at becoming a writer knows that this line of thinking is folly—there are no paths, only places where you put your feet.

Art: Angel Zarraga, The Poet (1917)