At Sunday’s Oscars show, five scripts will be up for Best Adapted Screenplay. Two of them are derivative dogs that have no business being anywhere near the Dolby Theater—Top Gun: Maverick and Glass Onion: A Knives Out Mystery, both considered “adapted” due to their being sequels—while the others, all of them with literary source material, make for an intriguing three-way race. So let’s focus on those three, shall we?

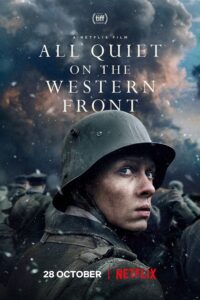

Trench-Warfare Porn

Based on the timeless anti-war novel by Erich Maria Remarque, All Quiet on the Western Front was co-written by Lesley Paterson, Ian Stokell, and director Edward Berger. It’s the third screen version of the novel, following Lewis Milestone’s early sound film (winner of the 1930 Academy Award for Best Picture), and a lesser 1979 TV movie adapted by Paul Monash. With the carnage in Ukraine now in its second year, this new retelling of an old story should feel timely and relevant.

If the first duty of an adapted screenplay is to remain faithful to the spirit of the source material while bringing something fresh to the game, this script is full of holes. The movie is a German production (it’s also up for Oscars for Best Picture and Best International Film), and the German press has pilloried the screenwriters for straying from Remarque’s revered text. Yes, Germans love to gripe — they’ve turned it into an art form—but this time there’s some merit to the sniping. For starters, the screenwriters introduce a group of cardboard officers and bureaucrats on both sides, who are apparently on hand to remind us that the First World War was an epic of official bungling, misunderstanding and misguided nationalist zeal. These dubious additions are overshadowed by even more dubious omissions. First, we don’t see the disillusioned soldier-narrator Paul Baumer (played here by Felix Kammerer) return to his hometown on a brief leave, a wrenching set piece in the novel that allowed Remarque to portray how the front had pulverized Paul’s generation and rendered them forever unable to fit back into with the world that made them. This was Remarque’s great theme, one honed by his own service in the trenches, where he was wounded five times but miraculously survived the slaughter. Another omission is the German soldiers’ brief flirtation with some French girls, which leavened the horror with some welcome levity and humanity.

If the first duty of an adapted screenplay is to remain faithful to the spirit of the source material while bringing something fresh to the game, this script is full of holes. The movie is a German production (it’s also up for Oscars for Best Picture and Best International Film), and the German press has pilloried the screenwriters for straying from Remarque’s revered text. Yes, Germans love to gripe — they’ve turned it into an art form—but this time there’s some merit to the sniping. For starters, the screenwriters introduce a group of cardboard officers and bureaucrats on both sides, who are apparently on hand to remind us that the First World War was an epic of official bungling, misunderstanding and misguided nationalist zeal. These dubious additions are overshadowed by even more dubious omissions. First, we don’t see the disillusioned soldier-narrator Paul Baumer (played here by Felix Kammerer) return to his hometown on a brief leave, a wrenching set piece in the novel that allowed Remarque to portray how the front had pulverized Paul’s generation and rendered them forever unable to fit back into with the world that made them. This was Remarque’s great theme, one honed by his own service in the trenches, where he was wounded five times but miraculously survived the slaughter. Another omission is the German soldiers’ brief flirtation with some French girls, which leavened the horror with some welcome levity and humanity.

Instead of trying to mine this nuanced material, Berger and his co-writers pound us with two and a half hours of virtually nonstop machine guns, mortar explosions, bayonets, flamethrowers, hand grenades, gas, mud, blood, agony and terror. It’s a lot of action and a lot of noise, but it doesn’t rise above the level of trench-warfare porn. The movie is content to hammer its obvious message that war is hell waged by idiots and fought by pawns. Thanks for a reminder we didn’t need.

Women in a Hayloft

Women Talking opens with four of the most beloved words in Hollywood: “Inspired by true events.” This is a signal that the filmmakers intend to eat their cake and have it, too—that is, to take advantage of the added heft that comes with a “true” story while freely manipulating the truth to their own ends. Those four little words always put me on alert.

Yet Women Talking, adapted from Miriam Toews’s 2018 novel by the director/screenwriter Sarah Polley, is that rarest thing: a movie based on a book that is, largely on the strength of the script, an improvement on the book. Polley benefits from film’s power to delineate personalities with visual markers, which turns this ensemble cast into a group of vivid individuals. The novel, on the other hand, often comes off as a cacophony of undifferentiated voices. I found myself constantly flipping to the cast of characters at the beginning of the book, trying to sort out which of the various mothers, daughters and nieces is doing the talking. (It didn’t help that the dialog has no quotation marks.)

Yet Women Talking, adapted from Miriam Toews’s 2018 novel by the director/screenwriter Sarah Polley, is that rarest thing: a movie based on a book that is, largely on the strength of the script, an improvement on the book. Polley benefits from film’s power to delineate personalities with visual markers, which turns this ensemble cast into a group of vivid individuals. The novel, on the other hand, often comes off as a cacophony of undifferentiated voices. I found myself constantly flipping to the cast of characters at the beginning of the book, trying to sort out which of the various mothers, daughters and nieces is doing the talking. (It didn’t help that the dialog has no quotation marks.)

Toews made the daring decision to do away with conventional suspense. In a brief opening note, she lays out the back story, which, by itself, could have been the stuff of a compelling novel:

Between 2005 and 2009, in a remote Mennonite colony in Bolivia named Manitoba Colony, after the province in Canada, many girls and women would wake in the morning feeling drowsy and in pain, their bodies bruised and bleeding, having been attacked in the night. The attacks were attributed to ghosts and demons. Some members of the community felt the women were being made to suffer by God or Satan as punishment for their sins; many accused the women of lying for attention or to cover up adultery; still others believed everything was the result of wild female imagination.

Eventually it was revealed that eight men from the colony had been using an animal anesthetic to knock their victims unconscious and rape them. In 2011, these men were convicted in a Bolivian court and received lengthy prison sentences…

Toews, who grew up in a Mennonite community in Canada, ends her note with this caveat: “Women Talking is both a reaction through fiction to these true-life events, and an act of female imagination.”

What Toews chooses to imagine is not the attacks on the women but the women’s deliberations on how to respond to them. The novel is narrated by the community’s schoolteacher, August Epp (played in the film by Ben Whishaw), who has agreed to write down minutes of the two meetings the illiterate women hold while the men accused of assaulting them are in town trying to post bail after their arrests. The clock is ticking. The men are due back in two days, and by then the women must agree on one of three courses of action: do nothing; stay and fight; or leave.

It’s a risky strategy to throw away so much potential suspense and opt instead for what amounts to a kitchen sink drama played out in a hayloft. On the page, the talk often sounds implausible for illiterate women who have led cloistered lives. Here, for instance, is one of the mothers offering her rationale for wanting to leave the colony: “We have ruled out staying and fighting because our faith consists of core values, one of them being pacifism, and we have no homeland but our faith, and we are servants to our faith, and by being such we are assured eternal peace in heaven.” Core values? “Being such”? Sounds like a college-educated novelist talking.

Polley’s screenplay remains faithful to the spirit of the novel but also takes advantage of the story’s dramatic possibilities without stooping to cheap sensationalism. We see brief, brutal snapshots of the aftermath of the attacks: a woman waking from drugged sleep to realize she is bruised, bloody, violated; another spitting out her bloodied teeth; a third shouting as an attacker flees into the night. And this ensemble cast is superb, led by Ona (Rooney Mara), pregnant with the child of her attacker, dreamily attracted to August Epps but strong as iron and determined to take control of her life and the life of her child. The other women are, by turns, tender, angry, confused and bitter, torn between the desire to forgive and the hunger for revenge. Ona’s quiet determination proves infectious, and it leads the women to a decision that’s both heartbreaking and heartwarming.

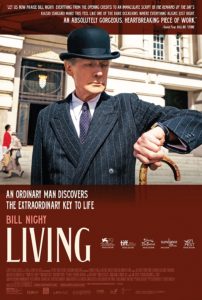

From Tokyo to London

Kazuo Ishiguro, winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature, drew on a formidable source when he wrote the screenplay for Living. His inspiration was the 1952 Japanese masterpiece Ikiru, which director Akira Kurosawa co-wrote with Shinobu Hashimoto and Hideo Oguni. To tell the story of a worn-out Tokyo bureaucrat named Watanabe (Takashi Shimura) who’s dying of cancer and makes a frantic stab to embrace life before it’s too late, the three writers drew on Leo Tolstoy’s 1886 novella, The Death of Ivan Ilyich. That tale spins around a stunner of a sentence: “Ivan Ilyich’s life had been most simple and most ordinary and therefore most terrible.” He’s dead on the first page, and the rest of the story consists of his deathbed realization that he has lived a thoroughly respectable and thoroughly pointless life. The novella is dark but inert: Ivan Ilyich lives his life, contracts cancer, has a belated and useless epiphany, then dies. End of the story.

To breathe some oxygen into this narrative, Kurosawa and his co-writers turned Watanabe into a man determined to salvage something from the last days of his own simple and ordinary and therefore terrible life. First he samples the pleasures of Tokyo nightlife, which he finds unsatisfying. Then he embarks on an ill-fated friendship with a much younger woman. Finally, he stuns his colleagues by turning the faceless and dysfunctional bureaucracy into an engine of change, pushing through the completion of a long-delayed playground. After Watanabe dies, a policeman tells the mourners that he saw a remarkable sight that has become an iconic image in film history: Watanabe on a swing in the playground, singing a sad song as snow gently falls. A triumphant end to a pointless life.

To breathe some oxygen into this narrative, Kurosawa and his co-writers turned Watanabe into a man determined to salvage something from the last days of his own simple and ordinary and therefore terrible life. First he samples the pleasures of Tokyo nightlife, which he finds unsatisfying. Then he embarks on an ill-fated friendship with a much younger woman. Finally, he stuns his colleagues by turning the faceless and dysfunctional bureaucracy into an engine of change, pushing through the completion of a long-delayed playground. After Watanabe dies, a policeman tells the mourners that he saw a remarkable sight that has become an iconic image in film history: Watanabe on a swing in the playground, singing a sad song as snow gently falls. A triumphant end to a pointless life.

As Ishiguro told the New York Times, “This is the weird thing about adaptation: part of you worships the original, but there has to be another side of you that’s ruthless.” And so Ishiguro has moved the story from 1950s Tokyo to 1950s London and pared the original story down to its bones. Now the repressed, dying bureaucrat is a widower named Mr. Williams (the superb Bill Nighy, who’s also up for Best Actor), a buttoned-down functionary who, like Watanabe (and unlike Ivan Ilyich), finds a sense of purpose during his last days. Ishiguro’s worship of his source material is evident in the way he hits all of Kurosawa’s high notes. What distinguishes this retelling is Nighy’s understated but powerful performance, backed by a fine supporting cast. Few upper lips have ever been stiffer than Mr. Williams’s, which makes his final act all the more astounding and satisfying.

The Envelope, Please!

Before we tear this thing open, we need to have a word about awards ceremonies. Writing recently in the New York Times, the Pulitzer Prize-winning critic Salamishah Tillet lamented the “false myth of meritocracy” that surrounds the Oscars and the Grammys. Tillet was particularly incensed at the absence of Black nominees for the Best Actress Oscar this year, and the fact that Beyoncé has never won the Grammy for Album of the Year. The culprit, Tillet contends, is that the movie and music industries (and, I would add, the book publishing, newspaper, theater, and art industries) remain predominantly older, white and male, despite some concerted efforts to diversify. It’s not just “Oscars Too White,” it’s “Culture Industry Too White.” Hard to argue with that. What I would argue is that artistic awards have never been solely about artistic merit, whether they’re presented in Hollywood, New York, or Stockholm. They are, first and last, marketing tools designed to boost the prestige and profits of the industries that created them, while, as an occasional bonus, lending those industries an aura of being attuned to lofty social concerns. The result is that material is often rewarded not on its merits but on the predisposition of the people doling out the awards—and on their willingness to pander to popular taste. How else, to cite just one example, can you explain Rocky winning the Oscar for Best Picture in 1977 over All the President’s Men, Taxi Driver, and Network?

And yet sometimes, in spite of themselves, these industries do reward genuine merit. I’m thinking about Tillet’s Pulitzer and Halle Berry’s Oscar for Best Actress and the Nobel Prizes bestowed on Toni Morrison, Seamus Heaney, Orhan Pamuk, and Alice Munro, to name a few. These worthies may be the exceptions who prove the rule, but their achievements have been noted and honored. The only “myth” about artistic awards is that merit is the only thing that matters. Sometimes it does, usually it doesn’t. So it goes. Let’s get back to the envelope.

And the Oscar for Best Adapted Screenplay Goes to…

Sarah Polley for Women Talking!

We should have seen this coming. Living is a nice little movie about an Everyman. Western Front doesn’t pay sufficient homage to its source material. Women Talking not only improves on its source material but also offers proof that even the most powerless women can assert themselves in the face of overwhelming male power, whether that power is in the hands of a Mennonite farmer in Bolivia or a movie mogul in Hollywood. And by awarding this Oscar to Women Talking, the movie industry is able to claim that it’s willing to face up to its own sins. (Three weeks ago, a Los Angeles court tacked 16 years onto Harvey Weinstein’s earlier 23-year sentence for sexual assault in New York.)

Let’s hope this Oscar is not merely the fruit of female imagination but an accurate reflection and a celebration of how the world is, at long last, beginning to work.