“Get them by heart, and then between you and me we’ll put them all in apple-pie order.”

— James Purdy, Jeremy’s Version (1970)

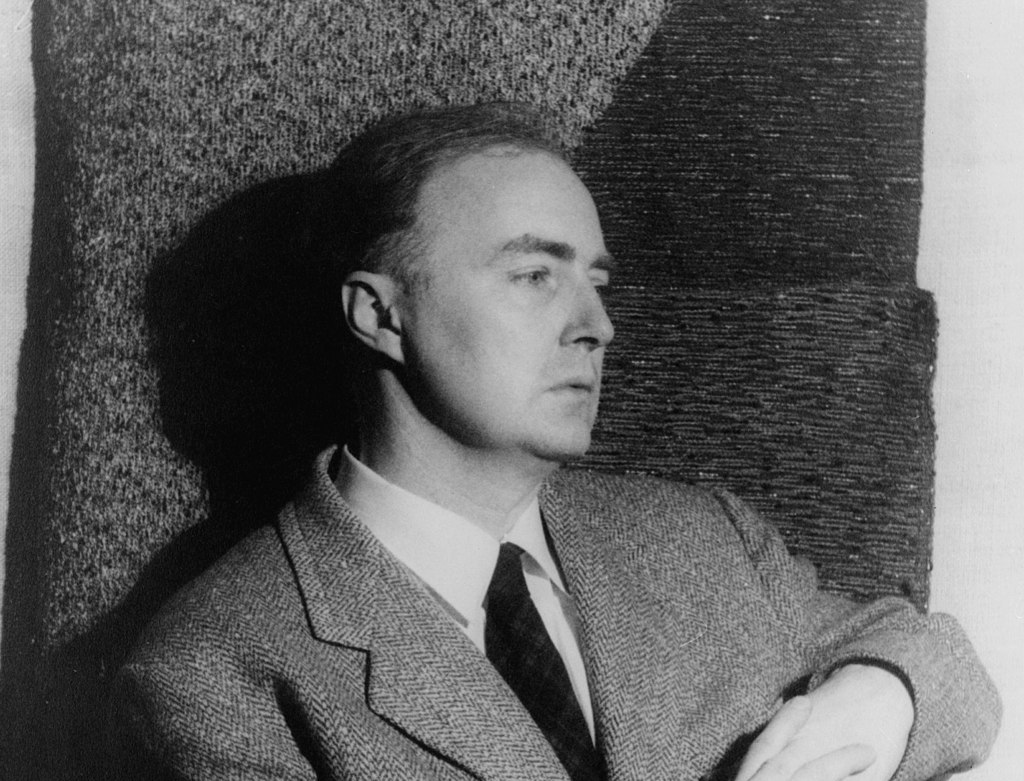

In October 1956, poet Dame Edith Sitwell sat in Montegufoni, the Sitwell family’s Tuscan castle, transfixed by the stories of an unknown American writer. On a hunch, James Purdy had sent her his privately published collection. He had been struggling to get published, and earlier that year, a wealthy friend generously financed the printing of Don’t Call Me By My Right Name. Purdy sent the slim volume, adorned with his Cocteauesque line drawings, to writers and critics with whom he thought his work would resonate.

Purdy mailed the book from New York, where he was visiting his older brother, Richard. He noticed a little post office near Richard’s hotel. He rapped on the door but a man said, “We’re closed!” Purdy looked so forlorn that the clerk let him in and examined his package to Italy. “What an address!” Purdy realized the clerk was Italian and seemed to know something of its destination. “This isn’t tied properly,” he remarked, and proceeded to retie it “beautifully.” “Then he gave me a long look, said ‘okay. Good luck.’ Good luck, he said. He never knew how wonderful that was; I often wondered if that Post Office existed. Maybe it just appeared for that one day. Well, that changed everything” because, had Edith Sitwell not liked the book, “I would have given up and never become a real writer.”

Though Purdy received responses to his collection replete with praise from legends such as Langston Hughes, Tennessee Williams, Elizabeth Bishop, and Thornton Wilder, the grandest of all to reply was Sitwell. Many revered Dame Edith as a magnificent poet and tastemaker—a visionary in the tradition of great English eccentrics. She was a stern critic but also a strong champion of her brother, Osbert Sitwell, and Denton Welch. After finishing Purdy’s collection, Sitwell felt compelled to write. Several stories were “superb; nothing short of masterpieces,” possessing a “terrible, heartbreaking quality.” She was so “deeply impressed by this book that, on the chance” Purdy had no British publisher, she had already written her London friend and publisher Victor Gollancz, advising him to acquire Purdy’s book. She hoped Purdy would soon “have another work ready.”

Stunned, James was prompted to send Sitwell his novella 63: Dream Palace, which another friend had paid to have privately published. In November, she responded that he was “really a great writer” and she was “quite overcome. What anguish, what heart-breaking truth! And what utter simplicity. The knife is turned and turned in one’s heart. From the terrible first pages—(the first sentence is, in itself, a masterpiece) to the heart-rending last pages, there isn’t a single false note.” Sitwell judged 63: Dream Palace equal to or perhaps “even greater” than the short stories and noted that her appreciation of the stories had only deepened since her first letter. She hoped they could meet when she would be in New York in early 1957. “You are truly a writer of genius,” she declared.

Through Sitwell’s intervention, Victor Gollancz published 63: Dream Palace: A Novella and Nine Stories in Great Britain in summer 1957, which led to New Directions publishing an expanded collection, Color of Darkness, in the United States late in the year. This in turn led to Farrar, Straus and Cudahy (later Farrar, Straus and Giroux) publishing four novels that established his reputation, beginning with Malcolm in 1959 and concluding with Eustace Chisholm and the Works in 1967. Sitwell reviewed his first British book in the Times Literary Supplement, again providing him with an invaluable introduction to the literary world. “Mr. Purdy is a superb writer, using all the fires of the heart and the crystallising powers of the brain.” He was in the “very highest rank of contemporary American writers” and 63: Dream Palace was “a masterpiece.” Within two years, she was convinced that “in the future he will be regarded as the greatest American prose writer of our time.” Going even further, Sitwell proclaimed: “I am convinced that in the future he will be known as one of the greatest writers produced in America during the last hundred years.”

Through Sitwell’s intervention, Victor Gollancz published 63: Dream Palace: A Novella and Nine Stories in Great Britain in summer 1957, which led to New Directions publishing an expanded collection, Color of Darkness, in the United States late in the year. This in turn led to Farrar, Straus and Cudahy (later Farrar, Straus and Giroux) publishing four novels that established his reputation, beginning with Malcolm in 1959 and concluding with Eustace Chisholm and the Works in 1967. Sitwell reviewed his first British book in the Times Literary Supplement, again providing him with an invaluable introduction to the literary world. “Mr. Purdy is a superb writer, using all the fires of the heart and the crystallising powers of the brain.” He was in the “very highest rank of contemporary American writers” and 63: Dream Palace was “a masterpiece.” Within two years, she was convinced that “in the future he will be regarded as the greatest American prose writer of our time.” Going even further, Sitwell proclaimed: “I am convinced that in the future he will be known as one of the greatest writers produced in America during the last hundred years.”

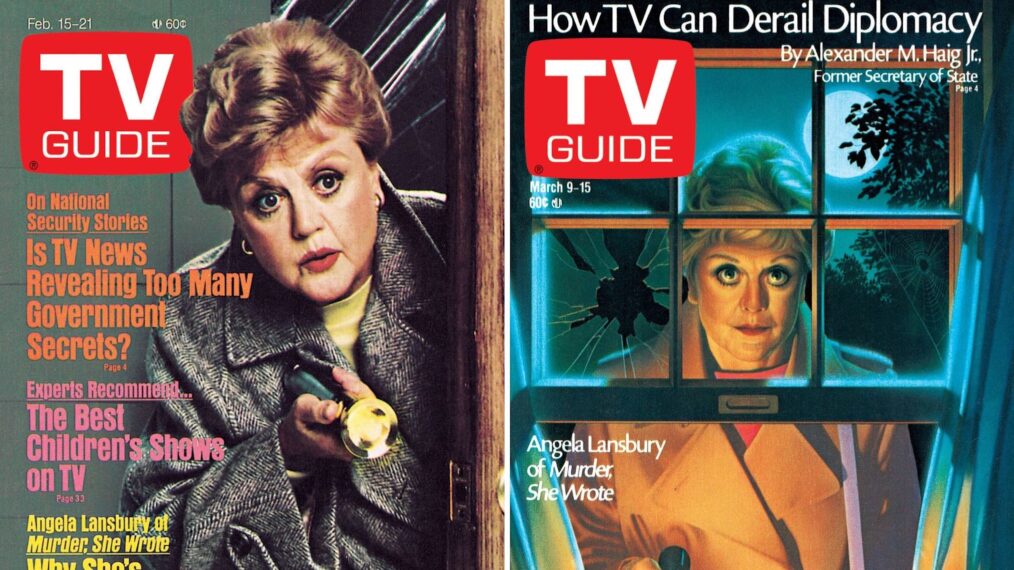

Dame Edith’s prediction never came to pass. Although Purdy’s critical reputation quickly grew, it peaked in the 1960s, and he never enjoyed a bestseller. Among mainstream readers his name remains obscure. Nevertheless, his work has influenced a host of major writers and accrued a diverse cult following that includes many gay or queer readers. This influence has been both direct and indirect. For example, the minimalist aesthetic of Gordon Lish, an influential editor, writer, and teacher, was largely guided by Purdy’s early stories. With Purdy in mind, Lish radically cut down Raymond Carver’s early manuscripts, cocreating the neo-minimalist Carver style that became famous. To Lish and several major figures like Jonathan Franzen, James Purdy was a visionary and an “authentic American genius,” as Gore Vidal declared. Since Purdy’s best work is on par with that of Melville and Faulkner, it is not surprising he was praised by the likes of Tennessee Williams, William Carlos Williams, and Joan Didion. Purdy’s literary significance has long been much greater than his sales and public recognition suggest.

As is the case with many novelists, Purdy’s work was personal, reflecting his own life experience. Through a unique alchemy, he transformed those raw life materials into powerful, symbolic works that critique American history, society, and culture—and especially, the family. To some degree, as scholar and critic Frank Baldanza wrote in 1974, Purdy’s vision touches the “experience of every American family.” Many critics failed to discern his work’s social and political edge, but Purdy insisted: “All of my work is a criticism of the United States, implicit not explicit.” His dogged investigation of American origins, ancestry, and identity constitutes a larger project—an “exploration of the American soul,” as he put it. English critic Stephen D. Adams described his works as a “cumulative endeavor to chart the ancestry of the national psyche.” Gordon Lish said Purdy’s work was regarded “as a sort of aberration, and reviewers attempt to account for him as such. But he is not an aberration at all. His work issues from the central American myths.” Alluding to William Carlos Williams’s book title, he added: “It is solidly in the American grain.” In Purdy’s only television appearance, he told a Dutch audience: “You see, people say I don’t like the United States. But I am the United States. You can only hate what you love, what you are a part of.” His work, Purdy wrote, was likened to an underground river “flowing undetected through the American landscape.” Archetypally, Purdy dramatizes crises of fate, identity, desire, and human nature, conveying a tragic sense of life couched in dark laughter.

As is the case with many novelists, Purdy’s work was personal, reflecting his own life experience. Through a unique alchemy, he transformed those raw life materials into powerful, symbolic works that critique American history, society, and culture—and especially, the family. To some degree, as scholar and critic Frank Baldanza wrote in 1974, Purdy’s vision touches the “experience of every American family.” Many critics failed to discern his work’s social and political edge, but Purdy insisted: “All of my work is a criticism of the United States, implicit not explicit.” His dogged investigation of American origins, ancestry, and identity constitutes a larger project—an “exploration of the American soul,” as he put it. English critic Stephen D. Adams described his works as a “cumulative endeavor to chart the ancestry of the national psyche.” Gordon Lish said Purdy’s work was regarded “as a sort of aberration, and reviewers attempt to account for him as such. But he is not an aberration at all. His work issues from the central American myths.” Alluding to William Carlos Williams’s book title, he added: “It is solidly in the American grain.” In Purdy’s only television appearance, he told a Dutch audience: “You see, people say I don’t like the United States. But I am the United States. You can only hate what you love, what you are a part of.” His work, Purdy wrote, was likened to an underground river “flowing undetected through the American landscape.” Archetypally, Purdy dramatizes crises of fate, identity, desire, and human nature, conveying a tragic sense of life couched in dark laughter.

In the 1960s, Purdy was familiar to aficionados of contemporary fiction, and his stories and novels were taught in colleges and even high schools. Purdy was praised by seminal critics including Brooks Atkinson, Ihab Hassan, Donald Pease, and R. W. B. Lewis, who rated Purdy alongside Ralph Ellison and Saul Bellow. In 1964, Susan Sontag declared “anything Purdy writes is a literary event of importance,” and he was “indisputably one of the half dozen or so living American writers most worth taking seriously.” Although Purdy’s name has since slipped under the radar of many critics and professors, Sontag underscored the “deservedly high place” he held “in contemporary letters.” Philosopher of language and novelist George Steiner said Purdy is “a writer of remarkable talent” whose books “take one by the throat and shake one’s bones loose.” His work embodies the “American language at its best.” Experiencing its “honesty and sensual immediacy,” its “power to make nerve and bone speak,” its “sharpness, integrity,” and “life-giving energy,” the reader’s “imagination emerges somehow dignified.” By 1990, however, readership, reviews, and academic attention had waned. Overseas, scholars Richard Canning in England and Marie-Claude Profit in France rated him a major figure, and he had a cult readership in Italy, but at home, he was either unknown or his reputation was overshadowed by controversy. The question of what caused this falling off has been repeatedly asked, but never quite satisfactorily answered. Why did Purdy’s works not become more popular during his lifetime? Why did he not become canonical instead of remaining a cult figure? Some have pointed to the diversity and uncategorizable nature of his work and the commensurate challenge of locating an apt critical approach to it; others point to the homophobia of many Cold War–era critics and publishers. In early stories like “Man and Wife,” Purdy bravely represented homosexuality with sympathy. Opening doors for later writers, Purdy boldly pushed the envelope in subject matter and literary strategy, following the frankly homoerotic early stories of Tennessee Williams. He was the first literary writer to publish the word motherfucker—which was bowdlerized in his first book by its English publisher. Cambridge literary scholar Tony Tanner contended that Purdy had never been done justice by many leading contemporary critics, who “simply don’t know how to read his work properly.” Six years after Purdy died, Jon Michaud assessed his oeuvre in the New Yorker: “Unsparing, ambiguous, violent, and largely indifferent to the reader’s needs, Purdy’s fiction seems likely to remain an acquired taste. But it is a taste worth acquiring.”

Part of the answer to Purdy’s never receiving mainstream recognition lies not in the work, but in the man. Over several decades, upset with publishers, editors, reviewers, and sometimes friends and partisans, he made reckless remarks and took actions that ill-served him. Looking back on Purdy’s career, composer Gerald Busby underscored a “big, important streak of selfdestructiveness.” He rarely agreed to sit for interviews and would not appear on American television. “He was precisely not playing the game. That delighted him.” He knew his worth: he was a major writer and “they had to play his game.” In the interviews he did give, he castigated major periodicals and critics of the East Coast publishing apparatus. Purdy would walk into “publishers’ offices and go on tirades.” Signed to numerous major houses, he would “alienate himself from each one.” He could “push anyone’s buttons, to get their attention,” Busby said. Jorma Sjoblom, Purdy’s lover and lifelong friend, said “he could be sharp in his criticism” and “alienated some people.” Running through publishers like fashion trends, Purdy vocalized his dissatisfaction with the recognition or promotion he received, which, at the best of times, was weighty. Over the decades, therefore, a growing list of editors and publishers crossed Purdy off their lists. A lot of people got back at him, Busby said. “He made enemies. They buried his books.” James Purdy was a staunch individualist, not a team player. He would “not play ball with the team” of the establishment, his friend James Link wrote, refusing to review their books, swap blurbs, or join official guilds. Instead, he identified with the individual fighter, attracted to images of bullfighters and boxers. In the 1940s he collected bullfight posters, and on his mantle and on the walls of his studio apartment on 236 Henry Street in Brooklyn Heights, he displayed several framed antique lithographs of boxers ready for fisticuffs. For a time, Purdy hung out in a New York gym where fighters trained, to listen to their talk. As a writer struggling to publish, battling baffled editors, homophobic reviewers, and stingy publishers, Purdy was a fighter. “Writing is like being a boxer,” he said in late career. “If you don’t want to get knocked down, you shouldn’t be in the game.” In Out with the Stars (1993), Abner Blossom, based on composer Virgil Thomson, tells his protégé: “I am above else a soldier and a fighter. For an artist never surrenders, never has in his possession the white flag.” He is the “fighting man forever. Battles are his lifeblood and energy. Fight! Struggle! Engage in mortal hand-to-hand combat. And then soar upward!” Or, as Ishmael Reed following Muhammed Ali put it: “writin’ is fightin’.” This was Purdy’s credo as he put up his dukes to agents, publishers, reviewers, and eventually, the entire Eastern literary establishment.

Part of the answer to Purdy’s never receiving mainstream recognition lies not in the work, but in the man. Over several decades, upset with publishers, editors, reviewers, and sometimes friends and partisans, he made reckless remarks and took actions that ill-served him. Looking back on Purdy’s career, composer Gerald Busby underscored a “big, important streak of selfdestructiveness.” He rarely agreed to sit for interviews and would not appear on American television. “He was precisely not playing the game. That delighted him.” He knew his worth: he was a major writer and “they had to play his game.” In the interviews he did give, he castigated major periodicals and critics of the East Coast publishing apparatus. Purdy would walk into “publishers’ offices and go on tirades.” Signed to numerous major houses, he would “alienate himself from each one.” He could “push anyone’s buttons, to get their attention,” Busby said. Jorma Sjoblom, Purdy’s lover and lifelong friend, said “he could be sharp in his criticism” and “alienated some people.” Running through publishers like fashion trends, Purdy vocalized his dissatisfaction with the recognition or promotion he received, which, at the best of times, was weighty. Over the decades, therefore, a growing list of editors and publishers crossed Purdy off their lists. A lot of people got back at him, Busby said. “He made enemies. They buried his books.” James Purdy was a staunch individualist, not a team player. He would “not play ball with the team” of the establishment, his friend James Link wrote, refusing to review their books, swap blurbs, or join official guilds. Instead, he identified with the individual fighter, attracted to images of bullfighters and boxers. In the 1940s he collected bullfight posters, and on his mantle and on the walls of his studio apartment on 236 Henry Street in Brooklyn Heights, he displayed several framed antique lithographs of boxers ready for fisticuffs. For a time, Purdy hung out in a New York gym where fighters trained, to listen to their talk. As a writer struggling to publish, battling baffled editors, homophobic reviewers, and stingy publishers, Purdy was a fighter. “Writing is like being a boxer,” he said in late career. “If you don’t want to get knocked down, you shouldn’t be in the game.” In Out with the Stars (1993), Abner Blossom, based on composer Virgil Thomson, tells his protégé: “I am above else a soldier and a fighter. For an artist never surrenders, never has in his possession the white flag.” He is the “fighting man forever. Battles are his lifeblood and energy. Fight! Struggle! Engage in mortal hand-to-hand combat. And then soar upward!” Or, as Ishmael Reed following Muhammed Ali put it: “writin’ is fightin’.” This was Purdy’s credo as he put up his dukes to agents, publishers, reviewers, and eventually, the entire Eastern literary establishment.

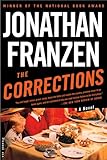

Thus, in one vein, his story is that of an uncompromising artist’s quixotic battle with the publishing establishment, taking them on, on his own. Pyrrhic victories, among others, were won along the way. Numerous friends uttered these six words: “He was his own worst enemy.” But from an alternate perspective, the fact that Purdy’s works of integrity and vision failed to reach a sizable audience is a condemnation not of a temperamental artist, but of a conservative, cliquey New York publishing world and book review system that failed to take risks to promote his eccentric genius. From the start, Purdy’s queer and transgressive content repelled and embarrassed some critics, and even some of his own publishers. Roger Straus, for example, refused to defend Eustace Chisholm and the Works after it was attacked in a homophobic hatchet job by another FSG author, Wilfrid Sheed. Nonetheless, Purdy’s loyal friends and admirers continued to spread the word, and interest in his writing and reissues of his books intermittently appeared. In 2005, Jonathan Franzen, celebrated author of The Corrections, nominated Eustace Chisholm and the Works for the Clifton Fadiman Award for Excellence in Fiction, bestowed upon an overlooked novel. In his award speech, Franzen declared: “Mr. Purdy’s novel is so good that almost any novel you read immediately after it will seem at least a little bit posturing, or dishonest, or self-admiring, in comparison.” For Franzen and many other readers, it was this dark, witty, and insightful novel about Daniel Haws—who ignores his Native ancestry and denies his love for another man—that hooked them. To Franzen, Purdy “has been and continues to be one of the most undervalued and underread writers in America.”

Thus, in one vein, his story is that of an uncompromising artist’s quixotic battle with the publishing establishment, taking them on, on his own. Pyrrhic victories, among others, were won along the way. Numerous friends uttered these six words: “He was his own worst enemy.” But from an alternate perspective, the fact that Purdy’s works of integrity and vision failed to reach a sizable audience is a condemnation not of a temperamental artist, but of a conservative, cliquey New York publishing world and book review system that failed to take risks to promote his eccentric genius. From the start, Purdy’s queer and transgressive content repelled and embarrassed some critics, and even some of his own publishers. Roger Straus, for example, refused to defend Eustace Chisholm and the Works after it was attacked in a homophobic hatchet job by another FSG author, Wilfrid Sheed. Nonetheless, Purdy’s loyal friends and admirers continued to spread the word, and interest in his writing and reissues of his books intermittently appeared. In 2005, Jonathan Franzen, celebrated author of The Corrections, nominated Eustace Chisholm and the Works for the Clifton Fadiman Award for Excellence in Fiction, bestowed upon an overlooked novel. In his award speech, Franzen declared: “Mr. Purdy’s novel is so good that almost any novel you read immediately after it will seem at least a little bit posturing, or dishonest, or self-admiring, in comparison.” For Franzen and many other readers, it was this dark, witty, and insightful novel about Daniel Haws—who ignores his Native ancestry and denies his love for another man—that hooked them. To Franzen, Purdy “has been and continues to be one of the most undervalued and underread writers in America.”

*

Writing a biography of James Purdy presents special challenges. He took pains to conceal his background throughout his career, tossing out red herrings about his past. He was reticent, even deceptive, in presenting basic facts, such as his birthdate. Even Jorma Sjoblom believed Purdy to have been nine years younger than he actually was. Purdy often claimed he was from Fremont, Ohio, but he was born in Hicksville and grew up in Findlay—forty miles from Fremont. His false claim was also a nod to Sherwood Anderson, whose Winesburg, Ohio was set nearby. Like Anderson, Purdy writes with compassion about the alienation and despair suffered by people in small communities who feel different, queer. Purdy’s evasiveness about these facts, his resistance to giving a chronology, and his rejection of past attempted biographers have thwarted a full-length biography until now.

Writing a biography of James Purdy presents special challenges. He took pains to conceal his background throughout his career, tossing out red herrings about his past. He was reticent, even deceptive, in presenting basic facts, such as his birthdate. Even Jorma Sjoblom believed Purdy to have been nine years younger than he actually was. Purdy often claimed he was from Fremont, Ohio, but he was born in Hicksville and grew up in Findlay—forty miles from Fremont. His false claim was also a nod to Sherwood Anderson, whose Winesburg, Ohio was set nearby. Like Anderson, Purdy writes with compassion about the alienation and despair suffered by people in small communities who feel different, queer. Purdy’s evasiveness about these facts, his resistance to giving a chronology, and his rejection of past attempted biographers have thwarted a full-length biography until now.

Purdy’s friend Tom Zulick remarked: “As much as he was a radical in some ways creatively, he was also a classical Midwestern man with classical ideas and mores, but informed by his intellect and his experiences as a gay man.” One pronounced theme running through Purdy’s life is instability and isolation at different periods, including his upbringing; another is his position as an outsider. As a gay man from the Midwest born in the early twentieth century, he identified with marginalized peoples: Natives (he claimed faint Ojibwe/Anishinaabe ancestry), black people, and the poor. To African American critic Joseph T. Skerrett Jr., Purdy’s work evidences his “emotional identification with the powerless, the stigmatized, and the frustrated.” Purdy was “suspicious of power,” and always responded to “the outsiders.” In the 1990s, Purdy was vexed by gay activists who asked, “When did you come out?” He rejoined, “I was born out.”

Delving into Purdy’s contrarianism, this biography seeks to understand why he was rarely content with the treatment he received from agents, editors, publishers, and critics. Regardless of how much praise he received, it never sufficed. This led contemporaries and friends, such as writers Joyce Carol Oates and Paul Bowles respectively, to wonder what it was Purdy wanted. As he sought recognition and promoted his books, his efforts often seemed to squander the goodwill extended to him. “James Purdy didn’t play the game of being a writer well,” said editor Don Weise, and he gained a reputation as difficult, even irrational. Purdy’s laments always center on a figure who had betrayed or neglected him, who was supposed to love and support him. These feelings perhaps have deep roots in Purdy’s early, troubled family dynamic—his oft-absent father, his parents’ divorce, and his mother who turned the family home into a rooming house.

Even visionaries are shaped by their times. This biography considers his life and works over his long career in their Great Depression, World War II, Cold War, late modernist, and postmodern contexts. Purdy insisted on radical artistic freedom, and with his liberal-anticommunist political stance, he was able, even as a gay and challenging writer, to easily benefit from American cultural capital and the support of the US government. He was part of a network of writers, scholars, critics, and publishers who had been in the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), and/or affiliated with its successor, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), the Congress for Cultural Freedom (CCF) that was secretly financed by the CIA, or other agencies promoting the image of the United States abroad, such as the United States Information Agency. Circa 1960, even a writer critical of the nation, provided he was not “red” or too “pink,” could be embraced by these bureaus as exemplifying American freedom of expression.

Purdy spent much time alone chasing his vision, but to meet him is to encounter his fascinating friends, who inspired him and became material for his narratives. Among them were Gertrude Abercrombie, a Chicago surrealist artist; Sam Steward, a Midwestern English professor and aspiring literary writer turned tattooist and pornographer; Chicago writer Wendell Wilcox, who, like Steward, was a friend and correspondent of Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas; and two gifted musicians, singer and composer Richard Hundley and pianist and composer Robert Helps, who was Purdy’s neighbor in Brooklyn Heights. Celebrity friends included Tennessee Williams, Virgil Thomson, Gloria Vanderbilt, and Ned Rorem; Edward Albee was a lifelong frenemy. At one party Albee invited him to at his large loft, after James arrived, Edward just stared at him. “I’m not sure Edward ever talked to him” that night, said John Uecker, actor, director, and Purdy’s longtime friend and assistant.

From the 1970s through his last years, Purdy attracted circles of younger friends and companions, and he exerted an enduring influence on a constellation of writers, composers, directors, actors, and artists. Some of them, like writer John Stewart Wynne, wrote well-received fan letters. Others, like John Uecker, met Purdy through mutual friends such as Virgil Thomson. Still others, like novelist Matthew Stadler, were enchanted after being assigned to review his work. These were mostly younger gay men, actors or writers who became intense admirers, often originally from the Midwest. Between Purdy and various combinations of acolytes was friendship, mentorship, brotherhood, and love; but also envy, rivalry, confusion, and, sometimes, hurt feelings. Some acolytes were excommunicated, some friends left of their own accord, but most who came into contact with James Purdy kept him in their minds and hearts for the rest of their lives.

James Purdy: Life of a Contrarian Writer both penetrates and celebrates mysteries of this enigmatic writer, while offering the first complete biography of him. In many cases, however, trying to solve a mystery just expands the scope of the mystery, or leads to more enigma. With so many participants gone, several puzzles of Purdy’s life may never be solved—and probably ought not to be.

From James Purdy: Life of a Contrarian Writer by Michael Snyder. Copyright © 2022 by Michael Snyder and published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved.