“This is rum. Read labels.”

This, perhaps, is the only time Don Draper emphasizes the importance of literacy to his only daughter, Sally. However, books play a massive role throughout AMC’s much-lauded, often-missed Mad Men. Literature high and low—from Lady Chatterly’s Lover to The Sound and the Fury, from Goodnight Moon to The Big Money—don’t just receive passing screentime, but often thoughtful discussion. The Mad Men Book Club attempts to contextualize those books’ place in the show, and further to explore and explode the textual and thematic connections that abound between the books and the show itself.

*

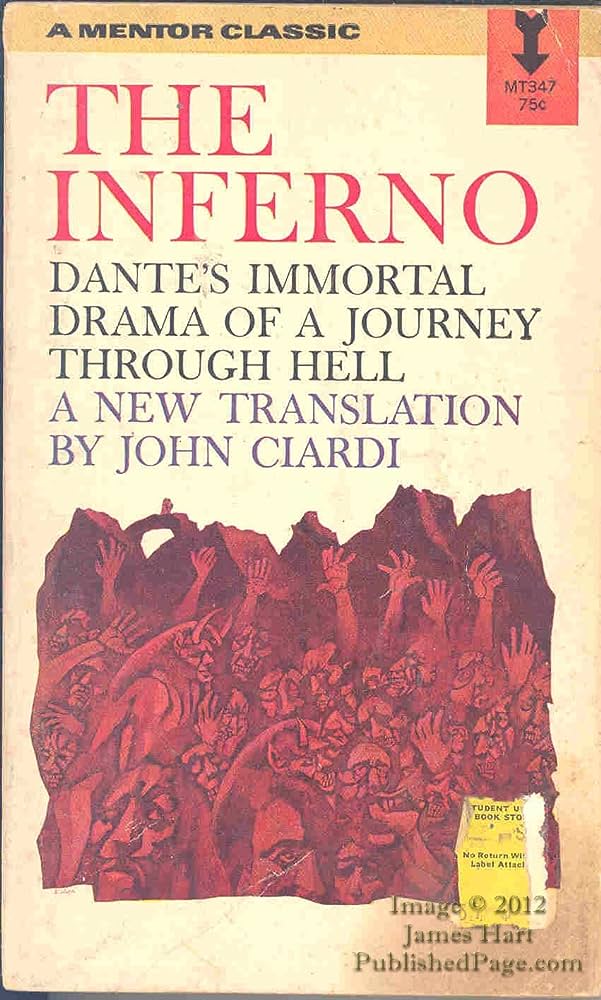

Don Draper—sun-kissed, mute—sits on the beach in Honolulu. Next to him, possibly more beautiful than she’s ever looked, his wife, Megan. We’re meant to wonder if Don has died. Moments earlier, Mad Men’s season 6 premiere had begun with a man desperately trying to resuscitate us, the camera. Is this heaven? Or perhaps hell. Back on the beach, Don clutches a copy of The Inferno, translated by John Ciardi. His voice, godlike, narrates:

Midway in our life’s journey, I went astray

from the straight road and woke to find myself

alone in a dark wood…

By the episode’s end, we’ll find ourselves at a New Year’s Eve gathering, with the Drapers sharing photos from their Hawaiian vacation with neighbors. With this, they usher in 1968, an American tour through Hell. In a series of interviews with the Television Academy, creator Matthew Weiner briefly reflects on the context of Season 6, noting that it’s the year “the history is in the show.” As in, the political and social events of 1968 became impossible to avoid. This was “the turbulent part of the turbulent 1960s,” he says, and “everything was seen through the prism of Vietnam.”

The prism, indeed, becomes a critical lens upon reflection. Familiar images, familiar tensions that Vietnam recalls pop up throughout the season from the jump: Don’s run-in with a soldier on R&R, Ken Cosgrove’s injuries sustained in Detroit, Sterling Cooper getting in over their head with their work with Chevy. “This is General Motors,” Ted Chaough says, as he and Don merge. “They fight the war with bodies on the ground.” Their hell in the workplace sealed with a handshake.

A hell of another kind, The Inferno itself needs little in the way of introduction, one would think, though I found plenty new in revisiting the text. It’s the first of a trilogy, the whole of the Divine Comedy, wherein we visit Purgatory in Part 2 and Paradise in Part 3. On Good Friday in the year 1300, Dante is taken through the depths and rings of Hell by the poet Virgil, and does so almost with a sense of fact-finding. Unlike most of my experience with fantasy, or even religious texts, there is precious little sense of a bigger picture, of looking back, even of lessons learned. A strength and a weakness in the text itself. It then does become like a religious text, which is to say much is open to interpretation as to the greater metaphorical meanings of Dante’s descent.

A sort of primary, or at least continual, takeaway of Dante’s is the loss of the ability to change. “What I was living, I am dead,” Dante is told, and thus he tells us. The pain the sinner causes is the pain they suffer for eternity—specific, and cruel. It calls to mind when PFC Dinkins, who Don meets in the season 6 premier, returns later in the season as hallucination. In California, where Don is often able to return to a sense of calm and reserve, Don mixes a little too much hashish with a little too much sun, and enters into a sort of psycho-reality only he tends to have access to. Perhaps not the highest ABV he’s ever hit, Don skulks around this party. Something somehow more true this season: Don is so big, so much bigger than the people around him, and when he does this walk, when he doesn’t have his wits about him, he can begin to pace and lurk like an upright shadow. In his trance, he sees Megan as a pregnant hippy, himself as David Hockney’s Portrait of an Artist lying dead in the pool, and Private Dinkins, without one of his arms. “Dying doesn’t make you whole,” Dinkins says. “You should see what you look like.”

The Inferno does properly introduce this season, though the comparison doesn’t always feel one to one. There is no proper Virgil showing us the way through Hell, no proper Dante observing. The employees of Sterling Cooper often feel more like the sinners Dante gets a peek at throughout his tour. Still, the imagery of Dante does often recall the dialogue of Madison Avenue, literally. The diagrams in Ciardi’s text —winding, meticulous, tedious, fictional—look like what like Roger Sterling describes in the season’s first episode:

What are the events in life? It’s like you see a door. The first time you come to it, you say, Oh, what’s on the other side of the door? Then you open a few doors. Then you say, I think I want to go over that bridge this time, I’m tired of doors… Look, life is supposed to be a path, and you go along and these things happen to you, and they’re supposed to change you, change your direction. But turns out that’s not true… you’re just going in a straight line to you know where.

Ted Chaough, too, notes at one point, “sometimes when you’re flying, you think you’re upside down when you’re right side up,” Indeed, the tone, the tension, of Dante’s Inferno often arrives in the same places. Think of Dawn, Don’s secretary, describing the terrors of navigating white corporate America: “Everybody’s scared there. Women crying in the ladies room, men crying in the elevator… I told you about that poor man hanging himself in his office.” Pete Campbell, surely, would leave 1968 calling Bob Benson a demon, and only partly because he helped orchestrate the murder of his mother. There’s the disgusting Herb Rennet, the ghouls that run Chevy— at the core of Mad Men, and of Dante, is the idea that we are always among sinners because we are all in fact sinners, guilty of either transgressions or apathy.

Indeed, the connections between Season 6 and the book are more thematic than anything else. Dante begins in Limbo, as Don does, possibly dead in Hawaii. The poets descend to the layer of Lust, just as we’re introduced to Sylvia, conveniently one floor below the Drapers. Then Gluttony, then Greed—like Don’s affair, like Herb Rennet of Jaguar, like biting off more than you can chew simply because you want the Chevy account. This next leads to Anger for Dante, as for Don toward Peggy, toward Ted. After Heresy, backsliding with Sylvia and scandalizing his child, Don resorts to Violence, punching, of all people, a pastor. Don’s Fraud comes to a head, with his daughter and with his company, where he resorts to Treachery, threatening to reveal Ted and Peggy’s relationship during a pitch-gone-wrong. Peggy calls him a monster, and she’s right. Here we are at Don’s lowest, a beast among his peers and loved ones.

It’s the way down, though, that indicates The Inferno. Perhaps the most depressing scene of this show—in a layer of Hell on Earth, a riotous New York City in the wake of MLK’s assassination—Don comes clean to Megan about his emotional impotence as a father:

I only ever wanted to be the man who loves children. But from the moment they’re born and that baby comes out, you act proud and excited and hand out cigars. But you don’t feel anything, especially if you had a difficult childhood. You want to love them, but you don’t. And the fact that you’re faking that feeling makes you wonder if your own father had the same problem.

He’s been drunk for days to try to mask this guilt, perhaps even to gain access to some heightened notion of whatever Don does feel it means to be a parent. “You see them do something,” he tells Megan, “and you feel that feeling you were pretending to have… and it feels like your heart is going to explode.” Season 6 marks Don’s final descent, that falling man from the opening credits finally hitting the ground. Here, finally, Don is done grasping at the air above him. As we dive deeper into Hell with Dante, do we lose touch with our human tendencies, does our grasp on what it means to love begin to falter, and are we absent from our roadmap to return to reality — how do we ascend after our descent?

The first half of Season 7 finds Don in purgatory, with his job and his marriage both up in the air, and the final image of the series is ostensibly one of paradise. Stop me if you’ve heard this before, but the way out—at least to Dante, and possibly to Don—may be through. There’s no epilogue to The Inferno, just the sequels. No time or moment to assess the damage, discuss what we’ve learned, decide what we might do differently in the future. No, the final moments of the story are arriving in the very bottom of Hell, seeing the horrors of Dis, of Satan. His three faces, weeping from his six eyes, trickling tears “mixed with bloody froth and pus.” To escape, the poets have to climb the beast himself. Gripping his skin—in some translations, holding him by the neck—gravity inverts on itself, and they descend and ascend simultaneously out of Hell. As Ciardi, the translator, notes, this is “a last supremely symbolic action.”

Seeing the beast, struck with that fear and awe, Dante: “I did not die, and yet I lost life’s breath: / imagine for yourself what I became, deprived at once of both my life and death.” Season 6 ends with a revelation: first for Don himself, and then passed down to his children. In the finale, he takes his kids to the dilapidated brothel of his childhood. “This is where I grew up,” Don tells them. It’s these final moments of the season, to me, that recall the final moments of The Inferno. The crushing cynicism you’re susceptible to when your innocence was ripped from you, the lens through which you’re forced to take in the world—it becomes a dark prism, not unlike the inverted cone through which Dante dives: kaleidoscopic, psychedelic, bleak. Perhaps naming it, that cynicism, showing it to those who love you, can be a way of momentarily holding your demons by the throat, allowing those around you to see the light to escape into, to ascend to that place before paradise.