As Patrick deWitt’s The Librarianist rolls along, readers might wonder if the Canadian humorist has finally settled down to write a “normal” novel. DeWitt has made his name peddling in surreal quirk, or as The New Yorker calls it, “stealth absurdism.” His oeuvre traces the footsteps of a Tom Robbins or perhaps a Roald Dahl, the surface world a cellophane-thin façade stretched across humanity’s unabashed weirdness.

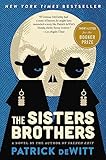

A 2011 Booker nominee, deWitt has employed these sensibilities to literary acclaim. Two of his novels—2011’s The Sisters Brothers (atmospheric, gruesome) and 2018’s French Exit

(atmospheric, gruesome) and 2018’s French Exit (liquor-fueled, also gruesome)—have even been adapted into films. Not to be outdone by Hollywood, his 2015 oddball fairy tale Undermajordomo Minor

(liquor-fueled, also gruesome)—have even been adapted into films. Not to be outdone by Hollywood, his 2015 oddball fairy tale Undermajordomo Minor climaxed in a sequence of unforgettable, indeed, memory-searing luridness. This is to say that deWitt traffics in a certain kind of plot and character. A portfolio such as his forges expectations. But in the first hundred-odd pages of The Librarianist, these expectations are unmet. More so, they miss the mark entirely.

climaxed in a sequence of unforgettable, indeed, memory-searing luridness. This is to say that deWitt traffics in a certain kind of plot and character. A portfolio such as his forges expectations. But in the first hundred-odd pages of The Librarianist, these expectations are unmet. More so, they miss the mark entirely.

The Librarianist concerns one Bob Comet, a demure divorcee who’s spent his life between the pages of books and, notably, between but one pair of legs (“Bob could never relate to the crude male perspective regarding the mysteries and machinations of sex”). Bob begins this tale as an old man, but even as the novel rewinds—from his retirement, to his spousal courtship, to his childhood—he can’t kick the septuagenarian mannerisms. It seems that Bob Comet was born to be an old person. And likewise, a librarian.

“[Bob] read adventure stories exclusively and with the pure and thorough commitment of the narcotics addict up until the onset of adolescence,” the novel’s omniscient narrator tells us, “at which point he discovered the dependable literary themes of loss, death, heartbreak, and abject alienation.”

Here, a perfunctory note on bookworm protagonists. O, low-hung literary fruit! Readers love reading, sure, but do they love reading about reading?

Plowing through novels doesn’t propel on-the-page action, and a limitation of writing bookworms is that these characters become tied, through the fourth wall, to the audience. Especially in the case of The Librarianist, wherein Bob’s bookishness fuels grim isolation, deWitt fans may table their hardback and step out for a breath of fresh air. Or a pint with a real live friend.

Speaking of which, Bob Comet’s social pursuits form the crux of this work. The aged bachelor claims comfort in solitude but craves platonic relationship and acts accordingly. deWitt has a penchant for intractable characters, and his novels tend to investigate what happens when these figures are thrust—often unwillingly—into motion. Bob fits this description to a tee, but his need for interaction had me questioning his hermit credentials. This opens a can of worms: Has Bob spent his life around books because he enjoys them, or because he’s too weak to accomplish anything else? A terrible question for a writer to ask, I’ve asked it nonetheless.

The Librarianist is essentially three novellas mashed into one lumpy albeit nourishing superstructure, concluded with a brief coda. Bob plays principal throughout, making repeated forays into the larger world only to be rebuffed by circumstance and his own timidity. Appropriately, deWitt kicks off his ode to isolation in nursing homes, specifically the very sad, very understaffed Gambell-Reed Senior Center in Portland, Oregon. Steered to the complex by an AWOL inmate—er, resident—Bob volunteers on account of his loneliness.

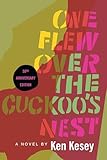

These are the terms on which we meet Mr. Comet, and suffice to say, they aren’t pretty. I felt less pity for Bob here than for deWitt, who seems to have performed an exhaustive study of our live-in care system. This first section of the novel reads like a toothless (or maybe just sober) One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest . As usual, deWitt does wonders with dialogue—“When we gamble, we’re asking the universe what we’re worth, and the universe, terrifyingly, tells us”—and one way to digest his novels is as a detached flaneur, similar to “watching” a Jarmusch film. The issue here is that deWitt has already spoiled us, particularly in The Sisters Brothers, with stellar plotting. In the Gambell-Reed Senior Center, there’s not much to grab hold of.

. As usual, deWitt does wonders with dialogue—“When we gamble, we’re asking the universe what we’re worth, and the universe, terrifyingly, tells us”—and one way to digest his novels is as a detached flaneur, similar to “watching” a Jarmusch film. The issue here is that deWitt has already spoiled us, particularly in The Sisters Brothers, with stellar plotting. In the Gambell-Reed Senior Center, there’s not much to grab hold of.

Things gain speed in the novel’s second section, where a much younger Bob meets his sheltered yet feisty bride-to-be, Connie, and then his first and only friend, Ethan, with whom Connie soon runs off.

“Don’t you like kids?” Bob asks Connie near the start of their involvement.

“I don’t know any kids,” she replies.

“Maybe you don’t like the idea of them.”

“No,” she answers, “to be honest, I don’t. It’s a steep investment for a woman, with unreliable returns.”

This Connie/Ethan segment is the heart of deWitt’s novel, and while it doesn’t explain Bob’s premature senility, dialogue rolls like a snare and romantic stakes feel sky-high. Since Bob has already told us how things end up, this is something of an adulterous postmortem. DeWitt doesn’t reach Updikean peaks but comports himself admirably as to why couples do the odd things they do.

In terms of oddity, here we reach a crossroads, for upon Connie’s leaving—“Bob still didn’t fully understand, he was not allowing himself to completely understand what had happened to his life”—The Librarianist continues to skirt deWitt’s stomping grounds. No one has yet been dismembered, manacled, or poisoned. Alcohol, while present, is not ascendent. And most strikingly, things just aren’t that strange.

Fear not. Like a mildly Tourettic missionary from some cult of the American bizarre, deWitt can’t fake a straight face for long. Here we rewind again and find Bob, aged 11, running away from home via commuter train and Greyhound bus. Stowing off to Oregon’s bucolic coastline, the reticent youngster finds himself among a two-woman, two-dog variety show taking up residency at an abandoned hotel.

Hoo-ha, I thought as the pups commenced a staggering ballroom waltz, now I’m reading deWitt. I’m probably a sucker for inanity—“You always hear about tramps buggering children,” one woman says of her dreams—but I enjoyed this final section perhaps more than was warranted given its detachment from the central narrative. If you’ve ever been to the Oregon Coast, as deWitt clearly has, you know it’s a place out of time and step with the rest of the ole’ contiguous. The same can be said of our last triptych panel, which involves wartime America, small-town showbiz, and an unrequited childhood crush, all of it rendered in the approximate spirit of Wes Anderson.

By now you’re likely wondering, where does this leave us? Is The Librarianist worth my time, or is it simply a sandwich with mismatched bits, bologna, say, with rhubarb and mackerel on a pretzel roll?

Really, reader, it’s both. This isn’t deWitt’s finest work, but then deWitt is a mighty fine author, and these can be hard to come by. If his newest novel occasionally limps along, it takes after Gerty MacDowell and does so with flair.