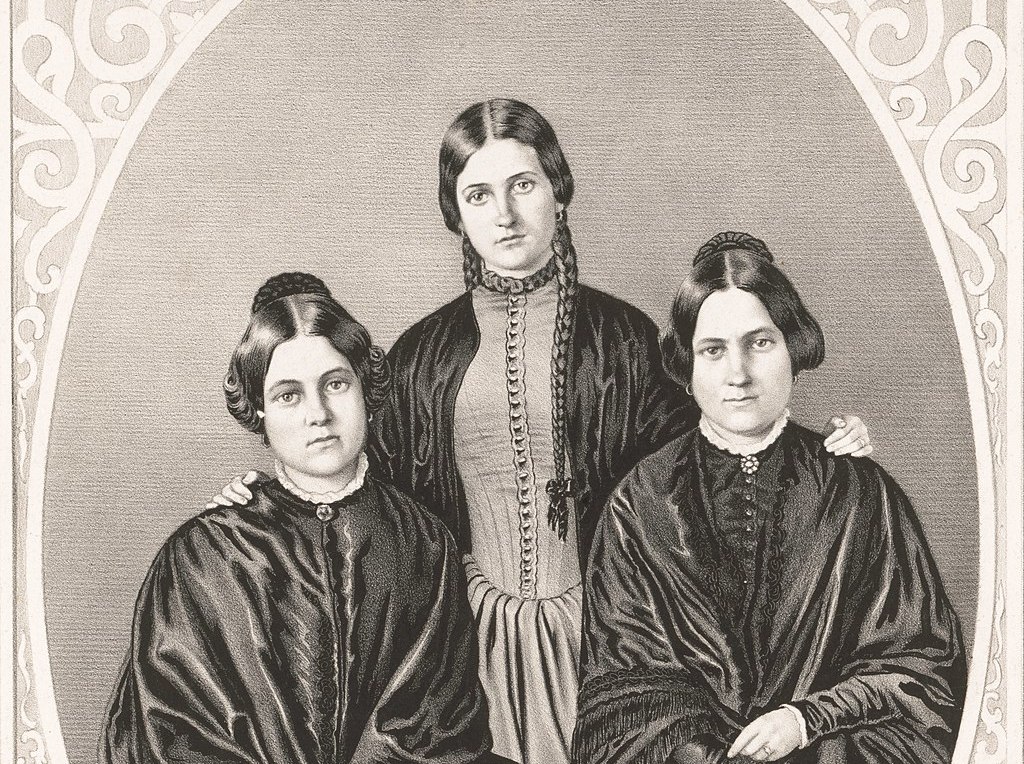

About six years ago, I was reading letters from Harriet Beecher Stowe to George Eliot in a locked research room at the New York Public Library. Here, I stumbled on a reference to a woman named Kate Fox. In an 1872 letter, the author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin told Eliot that she had recently encountered Kate—one of the Fox sisters, a trio of celebrated spirit mediums—at a séance. Stowe’s looping handwriting painted a vivid picture of the young woman conducting proceedings in the darkness, mysterious phosphorescent lights glowing all around her. Immediately intrigued, I set out to learn more about the Foxes.

About six years ago, I was reading letters from Harriet Beecher Stowe to George Eliot in a locked research room at the New York Public Library. Here, I stumbled on a reference to a woman named Kate Fox. In an 1872 letter, the author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin told Eliot that she had recently encountered Kate—one of the Fox sisters, a trio of celebrated spirit mediums—at a séance. Stowe’s looping handwriting painted a vivid picture of the young woman conducting proceedings in the darkness, mysterious phosphorescent lights glowing all around her. Immediately intrigued, I set out to learn more about the Foxes.

My library notes from that day would be my entry point into a shadowy Victorian world, full of women who attained fame, fortune, and astounding levels of social and political influence thanks to their supposed abilities to contact the dead. In the years that followed, I spent countless hours in library archives on both sides of the Atlantic, immersing myself in the nineteenth century Spiritualist movement, of which the Foxes and their peers were a part. Through my investigations, I discovered that some of these women leveraged their careers as clairvoyants to realize grander ambitions. Victoria Woodhull, a former spiritual healer from rural Ohio, became a highly influential figure on Wall Street, and later the first woman to run for the office of president of the United States. Georgina Weldon, a Londoner, was nearly confined to an asylum because of her beliefs in the spirit world, but went on to become a household name thanks to her campaigning against archaic lunacy laws. Emma Hardinge Britten, a fellow Briton, was celebrated as an orator, famed for giving speeches while in a trance; her renown was such that, after Lincoln’s assassination, she was asked to lead New York City’s first public commemoration of the late president, which was attended by thousands.

That these Victorian women, often with no formal education nor social connections, made such an impact in the male-dominated worlds of commerce, law, and politics struck me as remarkable. The twists and turns of their lives seemed to me the perfect raw material for a book. Of course, I anticipated that demystifying the complicated, sometimes morally dubious, parts of these women’s personalities might prove challenging, but it was a task I thought I would relish.

Instead, I came to accept that not all these complications could be fully demystified. Despite their tremendous achievements, it isn’t possible—nor advisable—to cast any of these women in a wholly heroic light. What’s more, I eventually realized that their lack of straightforward likability—something that, as a society, we demand far more of women than men—probably explained why the Fox sisters, Woodhull, Weldon, and Britten continue to languish in relative obscurity.

Although their names have fallen out of mainstream conversation, their contemporaneous popularity has ensured that there exists a wealth of information about these women—if you know where to look. Each of them either wrote memoirs—some published, some incomplete—or worked closely with their own biographers, and during their lives their exploits garnered plentiful newspaper column inches and became the subject of pamphlets and books. The difficulty for anyone wanting to know these women better today is that all of them were such polarizing figures that accounts tend to be extremely one-sided. Supportive voices—most prominently, their own—lavished them with praise; others roundly condemned them. Detractors took issue not just with the secretive worlds of spirit communication in which these women operated, but also with their subsequent careers as successful businesswomen, public speakers, or activists, which their Spiritualist platforms helped them forge.

Even in the years after the Victorian Spiritualist movement, most accounts about the women behind it continued to take the form of either all-out support or condemnation, even ridicule. A Plaintiff in Person, published in 1923 by Philip Treherne, the nephew of Georgina Weldon, for instance, was unsurprisingly loyal. Brian Thompson’s 2001 biography The Disastrous Mrs. Weldon, on the other hand, goes to considerable lengths to minimize the achievements of its subject’s life and dwells instead on her eccentricities, portraying her as lurching recklessly from one catastrophe to another.

Even in the years after the Victorian Spiritualist movement, most accounts about the women behind it continued to take the form of either all-out support or condemnation, even ridicule. A Plaintiff in Person, published in 1923 by Philip Treherne, the nephew of Georgina Weldon, for instance, was unsurprisingly loyal. Brian Thompson’s 2001 biography The Disastrous Mrs. Weldon, on the other hand, goes to considerable lengths to minimize the achievements of its subject’s life and dwells instead on her eccentricities, portraying her as lurching recklessly from one catastrophe to another.

Such books offer neater, more satisfyingly streamlined versions of these women’s lives than I felt able to produce. Treherne’s Georgina Weldon is decidedly heroic; Thompson’s, if not exactly villainous, is certainly a ludicrous figure. But the more I learned about these women’s lives the more I felt that, as their biographer, I needed to embrace their many contradictions. Where I could offer my own informed interpretations—for instance, of occasions when they claimed to have been summoning the dead—I would do so. But sometimes, when I couldn’t settle on a plausible alternative, I had to be prepared to simply stand back and trust my readers to draw their own conclusions.

I was aware as I was writing that many people would share my skepticism about these women’s purported talents. Few contemporary readers will be quick to accept that Victoria Woodhull could heal the sick through the touch of her hands; that the distinctive knocking sounds that reverberated around the Fox sisters’ séances were ghostly communications; or that during Emma Hardinge Britten’s trance-induced public lectures she was acting as a conduit for the messages of the dead. But context also matters: Take Britten and the controversial themes of many of her speeches—the need for abolition, women’s suffrage, and protections for “fallen women.” While history has largely cast her as either a genuine soothsayer or a scheming trickster, the truth could be decidedly more blurred: The stances that Britten took were often so incendiary—and inappropriate subject matter for a proper Victorian woman—that she may not have wanted to admit, perhaps even to herself, to having any part in their origination.

As a reader as well as a writer of biographies, I have long been drawn to books that acknowledge these kind of uncertainties and portray their subjects in their full complexity. I was recently challenged and moved by Paula Byrne’s The Adventures of Miss Barbara Pym, which ventures into territory that earlier works about this British author of bittersweet social comedies have often been at pains to avoid. Byrne includes the shocking truth that Pym had a relationship with an S.S. officer during her visits to Germany in the 1930s. Yes, this was well before Britain entered World War II, and before the full horror of Hitler’s political ambitions were understood by many people, but it nevertheless seems impossible that Pym could have been entirely oblivious to spreading stories of Nazi atrocities. As a longtime fan of Pym’s writing, I found this element of Byrne’s book deeply upsetting. It left me grappling with the difficult question of how a woman who writes with such finely tuned sensitivity about human nature in her fiction could, at least during this particular time in her life, have been so ignorant, so indifferent to other people’s suffering. This part of Pym’s story, though, undoubtedly gives the reader a more complete picture of her. Rather than reducing someone to the best or worst things they did, capturing a subject in their totality is usually more accurate—and compelling—biographical approach.

As a reader as well as a writer of biographies, I have long been drawn to books that acknowledge these kind of uncertainties and portray their subjects in their full complexity. I was recently challenged and moved by Paula Byrne’s The Adventures of Miss Barbara Pym, which ventures into territory that earlier works about this British author of bittersweet social comedies have often been at pains to avoid. Byrne includes the shocking truth that Pym had a relationship with an S.S. officer during her visits to Germany in the 1930s. Yes, this was well before Britain entered World War II, and before the full horror of Hitler’s political ambitions were understood by many people, but it nevertheless seems impossible that Pym could have been entirely oblivious to spreading stories of Nazi atrocities. As a longtime fan of Pym’s writing, I found this element of Byrne’s book deeply upsetting. It left me grappling with the difficult question of how a woman who writes with such finely tuned sensitivity about human nature in her fiction could, at least during this particular time in her life, have been so ignorant, so indifferent to other people’s suffering. This part of Pym’s story, though, undoubtedly gives the reader a more complete picture of her. Rather than reducing someone to the best or worst things they did, capturing a subject in their totality is usually more accurate—and compelling—biographical approach.

In Out of the Shadows, the book I’d eventually publish about my six Victorian celebrity Spiritualists, I decided early on that in addition to profiling the personal triumphs of these women I would avoid shying away from the aspects of their lives that drew (often justified) criticism. There are, for example, many well-documented instances of them deceiving their audiences or flat out lying about their own personal histories. Weldon became involved in an ugly public spat with the woman who helped save her from being incarcerated in an asylum; and Leah Fox, the sister of Kate, displayed an extreme hardheartedness to some of her closest family members. And most troublingly, in her later years, Woodhull actively promoted the repugnant philosophy of eugenics. I could not write about these women honestly and somehow extricate these actions from the qualities that also led them to take on the money men of Wall Street, run for the American presidency, or blaze a trail through Britain’s court system.

What I’ve learned through working on this book and sharing my world with these women for years, is that people and the lives they lead are complicated. And although the act of interpreting these complicated lives calls for a biographer to identify themes, patterns, and through-lines, it’s also okay to acknowledge the elements of a story that interfere with its expected shape. Biographies are not fables. They have no clear moral lessons. Rather, the messiness and uncertainty surrounding our subjects’ lives may in fact be the thing that keeps them most alive in our minds as we keep on trying, and failing, and trying again, to resolve the contradictions that make them human.

The post The Knotty Lives of Victorian Soothsayers appeared first on The Millions.