Mel Brooks has been making me laugh my whole damn life.

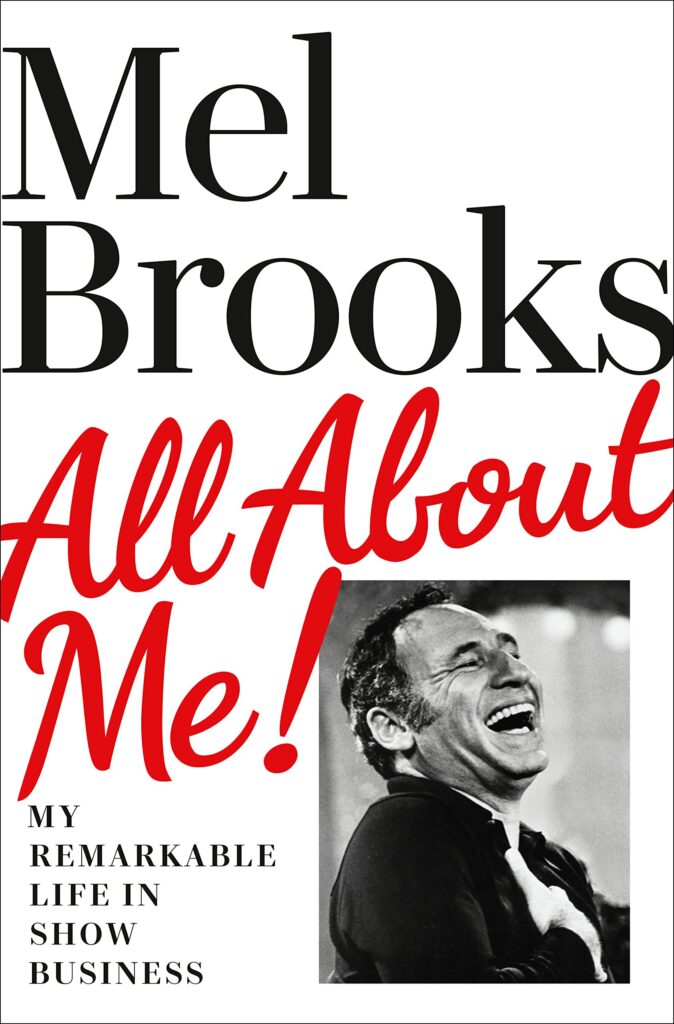

One of the first R-rated movies I ever saw was Blazing Saddles—the relentless flatulence of the beans-around-the-campfire scene reduced me to tears. In Spaceballs, Black Stormtroopers combing the desert with an afro pick (“Man, we ain’t found shit!”) destroyed me, as did the hilariously violent space diner dance number, though I hadn’t yet seen Alien. I’m not usually a fan of musicals, but I also adored the Rockettes-inspired sequence in Men in Tights, and all the dumb puns (“’Ey Blinken!” “Did you say ‘Abe Lincoln’?”). I am usually a fan of dumb puns, and there’s no shortage of them in Brooks’s new Hulu show, History of the World: Part II, the long-awaited-but-never-planned sequel to his 1981 film, History of the World: Part I. With the Mel Brooks Cinematic Universe (MBCU) expanding for perhaps the last time, I revisited Brooks’s bouncy 2021 memoir, All About Me!. In doing so, I realized that a) I’d only seen half his movies, and b) I didn’t actually know all that much about him. I didn’t even know that he’d been born Melvin Kaminsky, though it’s right there at the top of his Wikipedia page. (Brooks rebranded himself as a 14-year-old musician, swiping his mother’s maiden name, Brookman, then shortening it because it wouldn’t fit on his bass drum.) The shame!

To spare you the same indignity, I’ve collected some of the most memorable revelations about the diminutive icon who is probably the most prolific and successful comedy writer to ever live. (Ed. note: Evan wrote 15 revelations, but he fumbled five of them.) I hope that learning or remembering the absurd scope of Brooks’s career will inspire you not only to pick up his book—which is a joy to read—but to (re)watch all his films, as I’ve been doing.

Comedy nerds who already know all this stuff, please don’t yell at me.

*

I. Mel Brooks fought in World War II.

It makes sense that an American man born in 1926 would be drafted in 1944, but it’s still surreal reading about Brooks attending the Virginia Military Institute; earning his expert marksman badge; acquiring the taste of shit on a shingle; and, in 1946, being shipped off to a small village in Normandy to unearth landmines and check homes for booby traps.

To this day… if I enter a toilet with a pull chain behind the commode I have a tendency to stand on the bathroom seat and peer into the tank above to see if there is a booby trap… which hardly makes any sense in a restaurant in New York.

Brooks had it bad, but his older brother Lenny, an Air Force gunner, barely made it out alive. He was shot down and captured by Germans, who then held him in a POW camp for 19 months. If Lenny hadn’t tossed his dog tags—which had an “H” stamped into them, for Hebrew—and pretended to be Polish, he would have been sent to the concentration camps.

More than 40 years later, in 2008, Brooks turned down a Kennedy Center Honor from George W. Bush. He writes, “I didn’t want to be honored by Bush because as a veteran I was very unhappy about Americans being sent to war in Iraq.” In 2009, he accepted the award from President Obama, who is more of a drone guy.

II. By the time Brooks was 25, he’d already had several brushes with death.

Brooks has led such an exceptionally long and charmed life that he almost seems immortal—our little god of comedy. That perception is both threatened and reinforced by the many near-death experiences he recounts in his memoir.

Roller-skating around Brooklyn as a kid, he was run over by a car but miraculously emerged unscathed. (“Thank goodness it wasn’t a Buick or a Cadillac, or I wouldn’t be telling this story.”) Doing a sink-to-the-bottom-of-the-pool bit as a teen in the Borsch Belt, he, well, nearly drowned. (“For some reason I got even more laughs while gasping for breath.”) Then, of course, there was his stint as a combat engineer in WWII; even the day the war ended (Victory in Europe Day, or V-E Day) presented risk, as the celebratory bullets folks fired into the air would eventually rain back down. A fellow soldier named Richard Goldman instructed Brooks to hide with him in a cellar for 24 hours with food and wine: “Thanks to [his] savvy thinking, I’m still here,” Brooks writes.

But the potentially fatal encounter that stuck with me most involved Brooks’s old boss on the sketch program Your Show of Shows, Sid Caesar. Brooks describes Caesar as possessing superhuman strength (lifting up cars, throwing desks through walls, etc.) and a ballistically short temper. One night in 1950, the two of them were holed up in a Chicago hotel suite trying to write. “To help him relax,” Caesar had slugged half a bottle of vodka and lit a cigar. The room was filled with smoke, so Brooks asked Caesar to open the window, which was jammed shut.

…with a crazy look in his eye, he [Caesar] said, “So you want some air? I’ll give you plenty of air.”

He picked me up by my collar and my belt and hung me out the window! There was State Street directly below me! I could see the traffic so clearly; I knew which taxis were empty by the lights on the top.

Caesar didn’t drop him, obviously. But given how harrowing his early life could be, it’s no wonder that Brooks later told Mike Sacks, in Sacks’s terrific Poking the Dead Frog, that his work was “a chance to live a little longer… It’s like scratching your name in the bark of a tree. ‘I was here. I did something. I made my mark. And I will not be completely erased by death.’”

Caesar didn’t drop him, obviously. But given how harrowing his early life could be, it’s no wonder that Brooks later told Mike Sacks, in Sacks’s terrific Poking the Dead Frog, that his work was “a chance to live a little longer… It’s like scratching your name in the bark of a tree. ‘I was here. I did something. I made my mark. And I will not be completely erased by death.’”

III. The Producers had a long, winding journey to becoming a classic.

The seed for the 1967 film The Producers was planted in Brooks’s brain by a real-life producer named Benjamin Kutcher—the inspiration for the gerontophilic Max Bialystock and the story’s core premise. But Brooks originally envisioned it as a play called Springtime for Hitler. Kermit Bloomgarden, a Broadway producer best-known for Death of a Salesman, told Brooks that his idea had too many characters and scenes to be a play, saying, “What it is, is a movie.”

The seed for the 1967 film The Producers was planted in Brooks’s brain by a real-life producer named Benjamin Kutcher—the inspiration for the gerontophilic Max Bialystock and the story’s core premise. But Brooks originally envisioned it as a play called Springtime for Hitler. Kermit Bloomgarden, a Broadway producer best-known for Death of a Salesman, told Brooks that his idea had too many characters and scenes to be a play, saying, “What it is, is a movie.”

Brooks adapted his three-act play outline into a screenplay and shopped it around. Universal Studios was interested but wanted him to change it from Hitler to Mussolini. “Mussolini was a much more acceptable dictator,” he writes. “I think they just didn’t get it.”

Springtime for Hitler eventually found a home at Embassy Pictures. The studio head, Joseph E. Levine, said that there wasn’t a theater in the country that would put “HITLER” on its marquee. Brooks agreed to change the name, appreciating the irony of The Producers. A first-time film director, he also agreed to get more experience behind the camera—which he accomplished by shooting two Frito-Lay commercials in New Jersey.

The Producers didn’t make a big splash at the box office, and (unsurprisingly) it divided critics at the time. But today it’s considered a cult classic, and Brooks’s 2001 Broadway adaptation of the film, starring Nathan Lane as Bialystock and Matthew Broderick as Leo Bloom, won 12 Tony Awards—more than any other single production in history—elevating Brooks to EGOT status.

IV. Brooks adapted a Russian novel into a little-seen 1970 film called The Twelve Chairs.

When Brooks was writing for Your Show of Shows, the head writer, Mel Tolkin, shoved a copy of Nikolai Gogol’s Dead Souls in Brooks’s hands, telling him, “You’re an animal from Brooklyn, but I think you have the beginnings of something called a mind.”

When Brooks was writing for Your Show of Shows, the head writer, Mel Tolkin, shoved a copy of Nikolai Gogol’s Dead Souls in Brooks’s hands, telling him, “You’re an animal from Brooklyn, but I think you have the beginnings of something called a mind.”

Brooks calls Dead Souls a revelation, citing Gogol’s two-part alchemy of humanity and insanity. (In Poking a Dead Frog, Brooks talks about the profound influence Gogol has had not only on his films, particularly Blazing Saddles, but on his entire life.) Dead Souls ignited a lifelong love affair with Russian novels—including The Twelve Chairs by Ilya Ilf and Yevgeny Petrov.

Brooks calls Dead Souls a revelation, citing Gogol’s two-part alchemy of humanity and insanity. (In Poking a Dead Frog, Brooks talks about the profound influence Gogol has had not only on his films, particularly Blazing Saddles, but on his entire life.) Dead Souls ignited a lifelong love affair with Russian novels—including The Twelve Chairs by Ilya Ilf and Yevgeny Petrov.

Brooks adapted the novel into a film, which he shot in what was then Yugoslavia, despite an almost total lack of English-speaking locals and drinkable water. When an actor fell ill, Brooks stepped in to play the Russian servant Tikon, his first (but far from his last) onscreen role in the MBCU.

The Twelve Chairs also marks Brooks’s first collaboration with Dom DeLuise, “a gift from the comic gods!” DeLuise plays a conniving Russian priest; he would go on to become one of the most prominent members of Brooks’ acting stable, appearing in Blazing Saddles, Silent Movie, History of the World: Part I, and voicing Pizza the Hutt in Spaceballs.

The Twelve Chairs was released in October 1970. Brooks writes that “the picture did pretty well in New York… But it never made it across the George Washington Bridge.” He hypothesizes that over the past 50 years, it may have broken even on its roughly $1 million budget.

I recently watched The Twelve Chairs on YouTube with my parents—it’s funny, charming, and easy on the eyes. Besides the dazzling Adriatic scenery, a distractingly young and handsome Frank Langella elicited a lot of swooning from my mother.

V. Gene Wilder wasn’t Brooks’s first—or second—choice to play the Waco Kid.

The casting process for Blazing Saddles, which would become Brooks’s biggest box office hit, at first appeared cursed. Brooks had tapped Richard Pryor to play Bart, the Black sheriff, and he fought for him, but the studio balked because of Pryor’s personal issues. Though Pryor stayed on as one of the film’s writers, the fantastic, charismatic Broadway actor Cleavon Little landed the part of Bart. (Brooks writes, “Even Richard Pryor agreed wholeheartedly that Cleavon was the perfect choice for the role.”)

Next up was the Waco Kid, the drunken gunfighter who swiftly bonds with Bart. Brooks wanted “either a well-known Western hero or a well-known alcoholic” to play the Kid. With the former archetype in mind, he offered the part to John Wayne. Wayne, a huge fan of The Producers, loved the Blazing Saddles script but said it was too dirty for his fans. “My fans will accept almost anything,” he said, “but they won’t take dirty.”

Brooks’s second choice was Gig Young, an Oscar-winning actor and well-known alcoholic. Young got the gig—but on the first day of shooting he went full Exorcist, volcanically spraying vomit all over the set. It turned out that (despite his agent’s reassurances to the contrary) he was in the throes of withdrawal.

In a tear-soaked panic, Brooks called Gene Wilder, whom he’d plucked from Broadway to play Leo Bloom in The Producers. Wilder said, “I don’t know whether to laugh or cry, but I’ll be on a plane tomorrow morning.” He flew out the next day, a Saturday; by Monday, he was hanging upside down in a jail cell with cameras trained on his sweet, scruffy face.

VI. Gene Hackman didn’t get paid for his role as the blind man in Young Frankenstein.

While they were shooting Blazing Saddles, Brooks caught Wilder scribbling in a notepad between scenes and asked what he was working on. Wilder pitched him the idea for Young Frankenstein. Brooks asked how much money he had on him: “Fifty-seven dollars,” Wilder said. Brooks accepted it as a down payment for his work co-writing the screenplay for Young Frankenstein, which, incredibly, would be not only produced but released later that year in 1974.

Wilder used to play tennis every weekend with another obscenely talented Gene: Gene Hackman, who had recently won an Oscar for The French Connection. One such Saturday, Wilder told Hackman about Young Frankenstein, and Hackman asked if there were any parts he could play. “I’m dying to do some comedy,” he said. Wilder mentioned the blind hermit character, qualifying that it was just a cameo, and they couldn’t pay him his usual rate. Hackman didn’t care—he did the movie as a favor and accepted minor billing.

According to Brooks, when Young Frankenstein was first released, no one even realized it was Hackman playing the blind man until the end credits rolled. In a recent AMA on Reddit, Brooks praised Hackman as the most unexpectedly funny person he’d ever worked with. In the book, he writes, “I will always be eternally grateful to Gene Hackman for that gift of a performance.”

VII. Alfred Hitchcock served as an uncredited script consultant on High Anxiety.

Mel Brooks worships Alfred Hitchcock, hailing him as his own genre and “film for film, probably the best movie director that ever lived.” It was with a mixture of angst and glee, then, that Brooks set his sights on sending up Hitchcock for High Anxiety. With a rough draft of the script in hand, and fear in his heart, Brooks called Hitchcock to run the idea by him (“If he said no, I probably would have abandoned the whole notion”).

“Is this really Mel Brooks?” Hitchcock said. “I love your films. I loved Blazing Saddles. It’s absolutely miraculously funny.”

This was the beginning of a beautiful friendship. Every Friday afternoon, Brooks would visit Hitchcock’s office to eat roast beef and potatoes and talk about the script. “He was just wonderful,” Brooks writes. “He was like a silent partner. He would give me notes on the script and what he thought I should push.”

Brooks dedicated High Anxiety to Hitchcock, and Hitchcock was seated right next to him at the film’s premiere on Christmas Day, 1977. As Brooks watched his friend’s muted reaction, he felt a mounting dread, which peaked at movie’s end, when Hitchcock walked out of the theater without saying a word.

Soon after, though, Brooks arrived at his office to find a case of Chateau Haut Brion 1961, and a note:

My dear Mel,

What a splendid entertainment, one that should give you no anxieties of any kind.

I thank you most humbly for your dedication and I offer you further thanks on behalf of the Golden Gate Bridge.

With kindest regards and again my warmest congratulations.

Hitch

VIII. Brooks adopted a pit bull puppy from James Caan.

Among the many stars Brooks enlisted for his 1976 Hollywood meta-satire Silent Movie (Paul Newman, Burt Reynolds, Liza Minnelli, and of course his wife Anne Bancroft) was James Caan, who lived a block away from Brooks at the time.

After signing on to do the film, Caan told Brooks that his dog had just given birth to a litter of five puppies, and Brooks could pick one out. Brooks and Bancroft did so (or rather, the dog chose them), naming the tan-and-white pup Pongo, after the dog in One Hundred and One Dalmatians.

“We had no idea that we were getting a pit bull terrier,” Brooks writes. “We just thought he was beautiful. Later we were worried that he would do what pit bulls are stereotyped for doing, but he never ever bit anyone and was a sweetheart of a dog.”

Brooks’ family, particularly his son Max, adored Pongo, who lived to be nearly 15. The dog only had one flaw: sometimes he would climb up a hill and jump onto the roof of their Beverly Hills home. To get him down, Bancroft would have to coax him with Cheerios.

IX. George Lucas unwittingly provided the inspiration for the Yogurt merchandising scene in Spaceballs.

As he had with Alfred Hitchcock and High Anxiety, when Brooks was making Spaceballs, he reached out to George Lucas. Lucas (like Hitchcock, and Orson Welles, who narrated History of the World: Part I) loved Blazing Saddles and Young Frankenstein. He gave Spaceballs his blessing, with one caveat: no action figures. Spaceballs toys could look too similar to Star Wars toys, creating legal headaches for Lucas’s studio.

Brooks agreed, and the exchange sparked one of the funniest scenes in the film—when the Yoda knockoff Yogurt (played by Brooks himself) showcases all the merch in his cave, which is where the real money is at. “Spaceballs the T-shirt! Spaceballs the coloring book! Spaceballs the lunchbox! Spaceballs the breakfast cereal! Spaceballs the flamethrower! The kids really love that one.”

X. Brooks produced David Lynch’s The Elephant Man and David Cronenberg’s The Fly.

Being the world’s foremost funnyman means that as soon as people see you, they want to laugh. This became a problem in the late 1970s when Brooks wanted to branch out and produce movies that weren’t pure comedies or parodies. He knew that having his name on them would skew audience reactions. (I think we can all agree that “Mel Brooks Presents… The Elephant Man” would hit different.)

To put some distance between his brand and these films, Brooks formed his own production company, Brooksfilms. One of the early scripts he read for this new venture was The Elephant Man, which he pounced on. Seeking a director to helm Brooksfilms’ third feature, he saw David Lynch’s Eraserhead (“It was weird and crazy, but… it was a wonderful picture”) and set up a meeting with Lynch to see if he was the right man for The Elephant Man.

He’d only meet at one place, a restaurant called Bob’s Big Boy, where they served hamburgers and milkshakes…. When I first saw him I thought, Am I meeting David Lynch or Charles Lindbergh? He had on a white shirt buttoned all the way to the top and was wearing a worn leather aviator’s jacket. I wasn’t expecting David to be so polite, but he wasn’t blowing smoke—he was genuine. He was an artist in his own right, and I was impressed with his work.

Lynch got the job, of course, and The Elephant Man netted eight Oscar nominations and two BAFTA wins, for Best Film and Best Actor (John Hurt).

A few years later, Brooksfilms produced David Cronenberg’s The Fly. The distributor, Fox, wanted a big name for the lead. But Brooks insisted on Jeff Goldblum, saying, “We need the right guy for the role, and that guy is Jeff Goldblum.” Fox relented. Goldblum then asked the producers to screen-test his then-girlfriend, Geena Davis, for the other lead, which she landed—her first starring role, and a star-making turn.

Brooksfilms produced 19 films, one as recently as last year (Paws of Fury: The Legend of Hank), as well as History of the World: Part II. For many of these films, Brooks’s role as producer is uncredited—which, when it comes to Solarbabies, is probably for the best.