French cartoonist Jean-Jacques Sempé’s favorite thing about New York is The New Yorker. The magazine that, since 1925, has celebrated humorous drawings to keep current events at arm’s length. The magazine whose uncompromising standards have allowed him to perfect his skills over the years.

Since 1978, over 100 of Sempé’s drawings have appeared in The New Yorker. Those drawings don’t always include New York, nor are they always necessarily based on a joke. Instead, they offer a collection of scenes where poetry discreetly flirts with reality, telling a story of an artist’s melancholy relationship with little details, where an idea of life and death is played out. Like a mirror that shows our reflection, his work only invites us to cheerful introspection with an anxious but benevolent irony.

Marc Lecarpentier: Do you remember your first trip to New York?

Jean-Jacques Sempé: Yes, quite well. It was in 1965, I believe, with my first editor at Denoël, Alex Grall. Philippe Rossignol, who ran the company, had invited me to accompany him. I knew that he spoke perfect English and knew the city well. I was delighted by this offer. We were simply tourists, simply visitors.

ML: From that first trip, did you like New York?

JS: Oh, yes, yes, very much so. But I was a little upset that I didn’t speak English. I really felt a bit lame for not speaking the language. This city seemed to me to be full of life. Everyone there was managing; everyone was trying to manage. What blew me away the most was something that I wrote about much later in the book Par Avion; it’s the ability of everyone to adapt: you’re in the street, well, it starts to rain, and immediately people offer you umbrellas. It stops raining; immediately, they no longer offer umbrellas; they offer you watches, ties, or something else. Everyone adapts very quickly to the situation. Paris seemed to me a tough city. Very, very tough…. A rather bourgeois city, very bourgeois. New York, not at all…. Perhaps because people there know what it is to come to a place and look for a job.

ML: What attracted you in the first place?

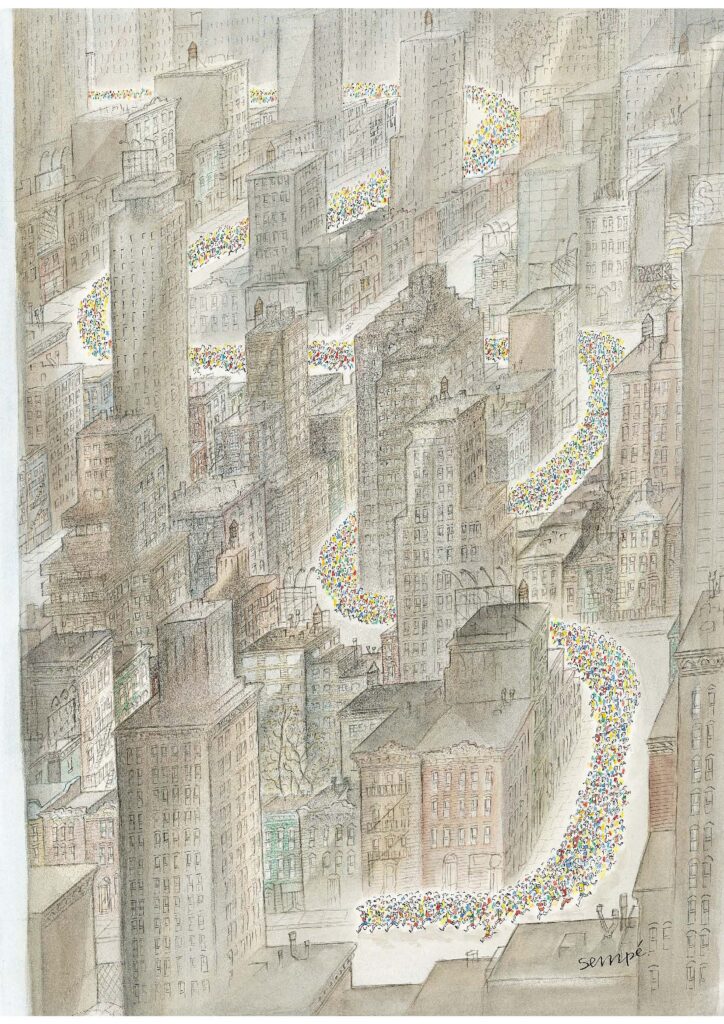

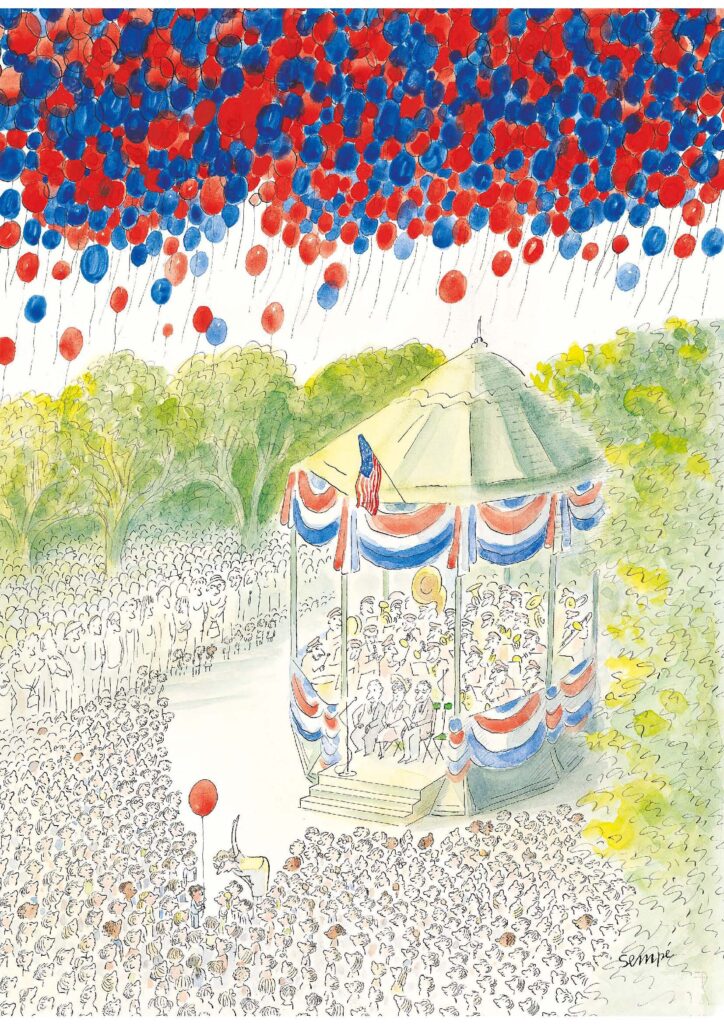

JS: The colors, I believe. New York is very colorful; there are many colors everywhere. Ah, yes! There are red, green, and yellow houses. While Paris is gray-blue, New York is very, very colorful.

ML: The city’s huge size did not astonish you or make you uneasy?

JS: Not at all! When I came from Bordeaux to Paris, I was shocked. I was astonished by the height of the Parisian buildings. But in New York, it seemed normal to me. I thought it was stunning.

ML: Not at all overwhelming?

JS: Oh, not at all! For me, it was precisely the opposite. In New York, there is plenty of room. And the air is better than in Paris! New York is a port city, don’t forget that! No, it isn’t overwhelming at all. That’s not the impression I got. Feeling tiny in the middle of the skyscrapers didn’t mean that I felt overwhelmed. I only felt tiny next to huge skyscrapers. This is life. It’s like being in a meadow in France on a sunny day with only a few clouds, and you can see into the distance. You don’t feel very big either, do you, at that moment? It’s always amazed me that human beings do not realize that they are—including me, of course—minuscule. We are truly tiny. So yes, in New York, it’s like that. When you go out, when you have an appointment, you know you’re going to this tall building or that tall building; there’s a kind of longing. There is such strength in these buildings, they’re so big, that you feel a kind of false energy because you have the feeling you are doing something! The feeling you are almost important, though you are not at all. That’s what I find so funny about New York. Everything becomes very important! A meeting is important. A meeting with someone is important. The word important is used all the time. As if every event counts. Without it, what would become of us…. But these are impressions. Obviously, I didn’t live there! I would have had to live there for several years.

ML: But did you still dream of working for The New Yorker?

JS: Oh, yes! I’ve always been a dreamer, so I didn’t think, “one day I’ll be able to,” but “one day, I will have the chance.” Which is not the same.

ML: What struck you most when you said, “I’m amazed by their talent”? What was original about The New Yorker compared to what you already knew about cartoons?

JS: The elegance of the line, and especially the sense of ellipsis.

ML: Saying without saying?

JS: That’s it, yes, the art of understatement. That’s what dazzled me, and also the wordless jokes. And then I discovered a lot of artists I didn’t know.

ML: So you tried to contact the magazine?

JS: Not at all! I was working for French newspapers and publishing comic books. I was terrified at the idea of confronting the demands of The New Yorker‘s editors, which I foresaw. So, for years, American and French friends asked me why I didn’t send drawings to The New Yorker, and I was only afraid they would refuse them. I used to reply: “I’m waiting for them to write to me,” knowing full well that they never wrote to anyone. So I was not risking anything! And when I went to New York for the first time, I only walked past the building a few times, not even daring to enter the lobby where so many people I admired went in. I was too much in awe. And then, one day, Ed Koren, who was drawing for The New Yorker, who spoke French and whom I had met before, came to my house with Jane Kramer, a reporter for The New Yorker. After interviewing me about general political issues, she left with one of my books and offered to show it to her editor.

ML: When the book left for New York, you waited with anxiety and hope.

JS: No, with anxiety. With great anxiety, with a tiny glimmer of hope. I didn’t know what to think. It was all too strange for me. Very strange. I didn’t really believe it. A few weeks later, disaster! I received a letter from the editor of The New Yorker, Mr. [William] Shawn, saying, “Look, we’d like you to send us drawings, covers, or whatever you want.” I didn’t sleep for a week; I was distraught. I didn’t know anything about American life when every aspect is different: an American window is unlike a French window, for example. And then I had to come up with ideas! What to do?

I tried to work anyway. That was all I could think about. And the art director of The New Yorker, Lee Lorenz, was in Paris and looked at my drawings and spotted two things he particularly liked and said would work for The New Yorker. Koren took the rolled-up paper with a cover and a series of drawings. He went to Orly, had lunch at a restaurant, and forgot my roll of paper when he left! He caused a flight delay so that he could go and retrieve it! To think of the trouble I caused him that day!

ML: And The New Yorker called you after receiving your drawings?

JS: Not at all! It was a New York friend who called me and said: “Your cover has been published! Your cover has been published!” I received the issue the next day. And I immediately went to buy another copy!

ML: And when you bought The New Yorker with your cover, you felt a certain happiness, I imagine?

JS: Oh, yes. I couldn’t believe it. I couldn’t believe it, even though it was a very simple drawing (Aug. 14, 1978). There couldn’t be many mistakes. And if there were mistakes, they didn’t exist anymore! So it was fine. And I got forty-seven letters from readers who wished to buy the drawing or to congratulate the editor of The New Yorker. It was a fantastic thing: forty-seven letters that people wrote! I was very touched.

ML: Did people in France realize how important it was to have a French cartoonist on the cover of The New Yorker?

JS: Yes, Roger Thérond, the editor of Paris-Match, knew it was important. Before discovering Bosc or Chaval, he had often published on the last page American cartoonists that I adored and still adore. But the other newspaper editors didn’t even know it. And what others were there?

ML: With the cover of The New Yorker, was the dream of a young courier from Bordeaux coming true?

JS: Of course. I staggered around for several weeks. But my stress never left me. Right away, I said to myself, “Now I have to keep going, I have to keep going, I have to find something, what to do, what’s happening in New York, what? A guy on a bicycle, well, no, they’re here but not over there.” And then one day, when I went to New York, the editor said, “Look, send us what you want and don’t think about The New Yorker, do what you want, that’s what I want, go ahead. Propose things to me.”

ML: The moment the editor of The New Yorker said to you, “Do what you want,” was that a relief?

JS: Not really. Because “Do what you want,” what does that mean?

ML: No constraints…total freedom!

JS: I wish I had known that feeling. But I also knew their standards and their strictness. Once, The New Yorker‘s art director had gone to London for an exhibition. The English journalists asked him: “What does it take for a drawing to be on the cover of The New Yorker?” He thought about it and answered: “What does it take for a drawing to be on the cover of The New Yorker? The New Yorker has to reproduce it and make the drawing its cover. Now it becomes a New Yorker cover.” That’s not stupid at all, what he said. It was strange, but that was the truth. We don’t know what it is, but it has to be that.

ML: One could say a New Yorker cover must make the reader dream?

JS: One could say that, but one might not….

ML: Because you have to create an atmosphere rather than a joke?

JS: Most importantly, it has to be original for them. It has to be peculiar. There has to be something surprising. We do our best, and that’s it. There are no fixed rules or pre-established parameters. The covers are, first and foremost, a mood. That’s what I like the most.

ML: Little by little, with the publication of covers and drawings, did you feel like you belonged to The New Yorker community? That you were part of the club?

JS: Part of a family. A family, yes. I had that feeling. And that was wonderful.

ML: Was it just a feeling?

JS: As with all families, it’s not the ultimate dream. But yes, when you join The New Yorker, you have the impression of being part of a family.

ML: And this idea of “family,” what does that mean?

JS: It’s simple: you exist!

ML: And before, you didn’t exist?

JS: No. The cartoonist’s profession never makes you feel like you exist except when you do a book, perhaps. But it’s a fleeting feeling! In France, we always have the feeling of being superfluous in the newspapers. A cartoon, when space is at a premium, is a luxury. A cartoon is a luxury product.

Excerpted from Sempé in New York. Reprinted by permission of 26letters.