How do you follow a masterpiece? Ideally with another. Such has been achieved by George Saunders. After his Booker Prize-winning novel, Lincoln in the Bardo—which feels, so far, like the early frontrunner for this century’s Ulysses—Saunders returns to literary fiction with another remarkable collection of short stories, Liberation Day. Those familiar with Saunders’s aesthetic will find the distinct features of his work have further evolved into delightful extremes. There’s the energetic language, the disciplined plot. He continues to introduce his high-concept premises without exposition, keeping the material strange. His characters—though tragic and hapless—are still treated with compassion. But there’s a clear change in the comedic sensibilities, an altered shade of the absurd, which allows Saunders to make this improbable advancement in his work.

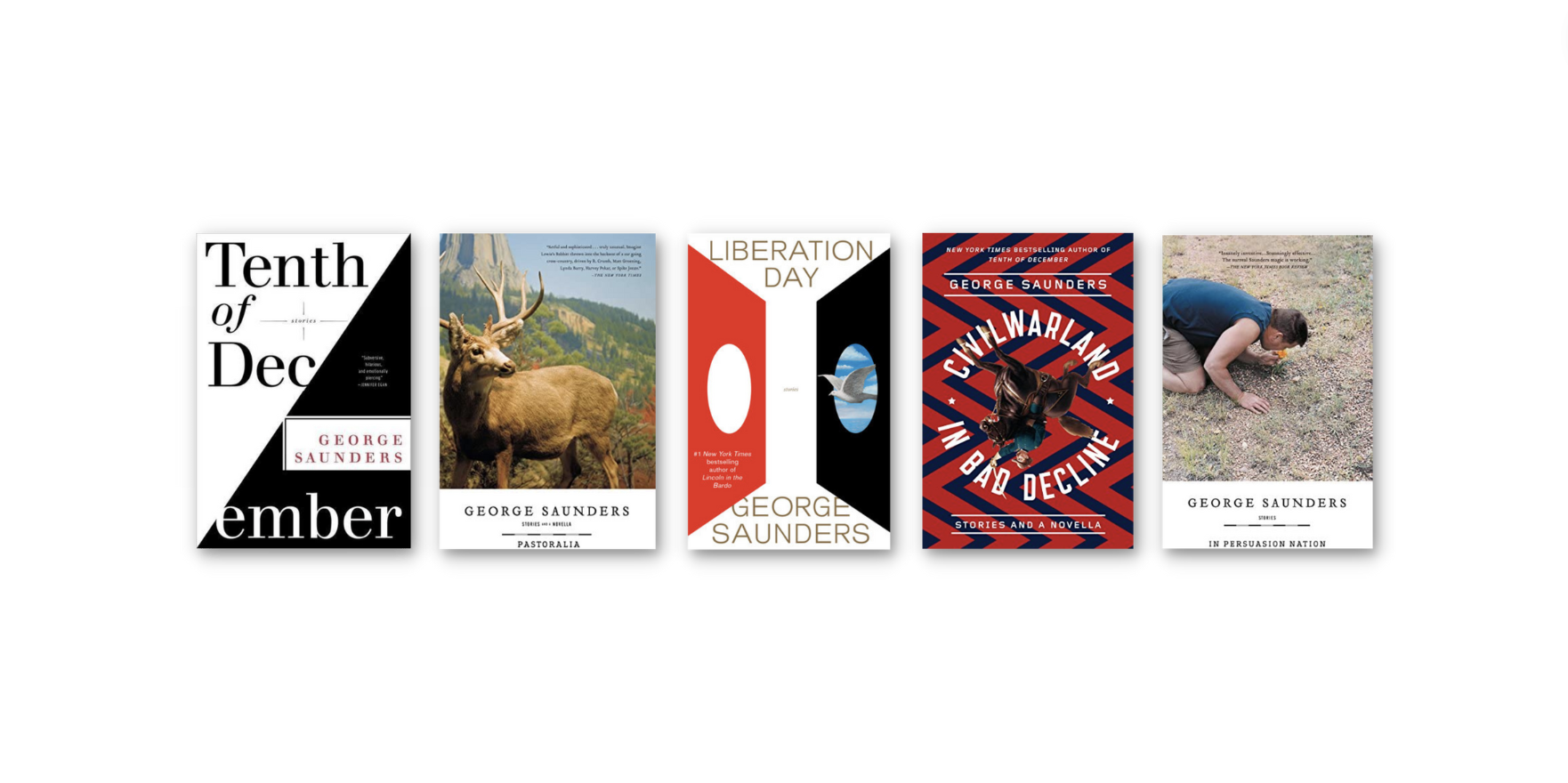

As a former student of Saunders’s, I understand I am not America’s first choice to objectively review Liberation Day. But as someone who recently reread all of his prior story collections, I want to examine a passage from each book—CivilWarLand in Bad Decline, Pastoralia, In Persuasion Nation, Tenth of December, and, now, Liberation Day—to consider how Saunders’s use and sense of humor have evolved over his short-story career.

My wife, hearing me laugh into a state of mild convulsion while rereading “The Four-Hundred Pound CEO” for the dozenth time a few months ago, said to me: “You look so happy.” It was true. I felt happy. Comedy in literature, I think, is more rewarding than in any other form. The laughter comes about from a kind of close attention rarely required of us in our days filled with sedating labor and visual ads. It’s something Saunders is very much aware of: throughout his career, language itself is the source and the object of his humor. And while his short stories are rightfully known for far more than their laughs, the comic is neither frill nor misdirection in his work. Rather, the language and the comedy are inseparable, much in the same way a map is necessarily connected to its represented geography: comedy occasions his voice, the combination of language systems that bring about that quality of Saundersness. So while it is notoriously tough to parse funny, and while there is also nothing less funny than trying to explain a joke, I hope to overcome both challenges in what follows by staying close to the language of his stories.

Let’s start with “The 400 Pound CEO,” a story from CivilWarLand In Bad Decline, in which a ridiculed overweight man who works for a falsely-ethical racoon-removal business becomes the CEO through an unwitting act of violence. Below is how Jeffrey, our narrator, describes himself:

These days commissions are my main joy. I’m too large to attract female company. I weigh four hundred. I don’t like it but it’s beyond my control. I’ve tried running and rowing the stationary canoe and hatha-yoga and belly staples and even a muzzle back in the dark days when I had it bad for Freeda, our document placement and retrieval specialist. When I was merely portly it was easy to see myself as a kind of exuberant sportsman who overate out of lust for life. Now no one could possibly mistake me for a sportsman.

Notice the unassuming start to the paragraph, specifically the “I’m too large…” But by the next sentence we learn an unexpected detail. Four hundred? It’s a surprising excess. The relationship between these sentences is key. We’ve moved quickly from the familiar to the exaggerated, and it’s this surprise that pushes the paragraph into the realm of comedy.

I weigh four hundred,” is an all-time favorite sentence of mine. I love the unqualified number. Four hundred what? Pounds? Stones? Tons? Unbound, the number becomes too grand to comprehend. It’s a recurring move in Saunders’s work, to defamiliarize a word or phrase by removing its usual context. The deadpan quality to the announcement is both funny and sad: Jeffrey seems to be telling us how much he weighs with his eyes closed, dismayed that it needs to be repeated. Syntactically, the sentence could not be simpler. Four words, five syllables, a single declarative statement. But the simplicity also allows for speed. Funny is fast and fast is funny. In this sentence, we have little friction, and this lets the delivery land. The simple structure also creates a useful symmetry: similar to the relationship between two sentences, the first half makes what follows surprising and compelling. Can we anticipate the end of the sentence from how it begins? Generally, yes—except in comedic writing, which Saunders knows. Lastly, we need to look at that verb, “weigh.” The most obvious alternative to “I weigh” is “I am,” but there’s a meekness in that construction, an insubstantiality. Here the word “weigh” feels like the idea it signifies. There is heft, density. It is a burden to weigh.

If this sounds cruel, Saunders lets us laugh by having Jeffrey state this is “beyond my control.” We are mostly laughing at the absurdity of his situation: the hopelessness, and the futile attempts to overcome this hopelessness. This is clear through the list that Saunders constructs, a list that begins with: “I’ve tried…” It’s another simple composition, the list, that delivers its comedy partly through its speed—there are no commas, no dashes, no chance to pause—and partly through its increasing specificity. Again Saunders begins with the mundane to jump to the hyper-specific. We move from “running” to “rowing the stationary canoe.” Using “rowing machine” would be a flatline, but “stationary canoe” provides an image of cramped and painful labor for Jeffrey. Then we’re into “hatha-yoga,” which, again unfamiliar, tells of the extreme measures Jeffrey has taken to try losing weight. There’s the “muzzle” he wore, an image sadly funny for how Jeffrey has been forced to humiliate and hurt himself. The more effort put into a hopeless situation, the more laugher that’s generated, because we, as readers, empathize with feeling ineffective in a painfully futile situation. And last in the list is what Saunders is perhaps most known for: his ability to call attention to the absurd dissembling in corporate speak; Freeda is the “document placement and retrieval specialist,” or someone who files things. But in the corporate parlance she is also inflated, she achieves a status too big for Jeffrey.

In a final comedic move that establishes Jeffrey’s wit, he describes his transition from possibly resembling a “sportsman” to his current state. He ends the paragraph with, “Now no one could possibly mistake me for a sportsman.” We’re given a disjunctive syllogism—by stating only what he is not, Jeffrey invites us to fill in the absence with what he is. It reinforces that Jeffrey is not the joke, but instead someone fully aware of the joke in which he exists.

In six sentences, the passage gathers registers from weight-loss programs, the workplace, the colloquial, and the ironically poetic. This is important: often what changes from story to story, from book to book, are the types of registers that Saunders arranges.

*

Much of the language in CivilWarLand In Bad Decline resembles an assured and lyrical spoken word. But there’s a shift in Pastoralia, the second book of Saunders’ stories, and below is an example from that collection, a passage from “The Barber’s Unhappiness.” The story involves a bitter barber who, in addition to his misanthropy, is plagued by a strange condition that leaves him with no toes:

Much of the language in CivilWarLand In Bad Decline resembles an assured and lyrical spoken word. But there’s a shift in Pastoralia, the second book of Saunders’ stories, and below is an example from that collection, a passage from “The Barber’s Unhappiness.” The story involves a bitter barber who, in addition to his misanthropy, is plagued by a strange condition that leaves him with no toes:

Later that month the barber sat stiffly at a wedding reception at the edge of a kind of mock Japanese tearoom at the Hilton while some goofball inside a full-body PuppetPlayers groom costume, complete with top hat and tails and a huge yellow felt head and three-fingered yellow felt hands, made vulgar thrusting motions with his hips in the barber’s direction, as if to say: Do you like to do this? Have you done this?

The overlap between this passage and Jeffrey’s monologue can be found in the speed with which the information is delivered. There’s little punctuation; the only pause is to further qualify the “groom costume.” But notice the difference overall in syntax. While the passage from “The 400 Pound CEO” builds toward a multi-clause sentence after a few declaratives, in this passage we begin with a brisk multi-clause sentence that leads to questions that, though considered by the barber, are also directed toward the reader through the use of second person. We’re arriving at what’s funny through an inversion of the technique from “The 400 Pound CEO,” where we conclude with a direct address, a comic narrowing. The question is not: “Does he like this?” Or: “Do you all like this?” It is “you,” the reader and the barber, who have, for the purpose of the joke, collapsed into the same person. The barber is in a situation we understand to be absurd because we are brought there, to the exact same place, in the unfortunate aim of the yellow thrusts.

Try reading this paragraph aloud. From the start you’ll feel a different lingual texture than Jeffrey’s monologue. It feels rounded and breathless, no staccato. This is partly attributable to the change in perspective, where a greater range of cadence is available to the slightly removed third-person narrator, a notable shift for Saunders between his first two books. The six stories and the novella that compose CivilWarLand in Bad Decline are all in the first person, but only two of the six stories in Pastoralia use first-person narration. While closely tied to the barber’s consciousness, the narrator of “The Barber’s Unhappiness” is a third-person perspective; it is not the barber composing the entirety of the sentence above, describing how he himself sat “stiffly” at the wedding. The perspective shift in Pastoralia allows Saunders to do what he does best comedically: to be both outside and of. He makes fun of his characters while empathizing with their suffering.

I’ll end my analysis by returning to the passage’s exuberantly unusual combination of nouns. This is a pattern in all of Saunders’s comedy, the hyper-specific linked unexpectedly. The process is similar in spirit to how a writer creates a beautiful image through a surprising juxtaposition, but the effect depends on the type of objects juxtaposed. Consider the following words and phrases out of context, as if in a word bank for a child’s game: barber, wedding, Japanese, tea, Hilton, goofball, PuppetPlayers, vulgar, motions—what, exactly, do these words and phrases have in common? Saunders sees a connection.

*

There’s the well-documented satire in all of Saunders’s work, but the satire found in his third collection, In Persuasion Nation, feels different, partly because the subject being satirized is more often separate from the characters. Below is a passage from “Brad Corrigan, American,” a story set in a metaphysical sitcom world in which Brad is in danger of being written out of the show for his empathy toward a group of speaking corpses, who were killed in an act of genocide and have now appeared inexplicably in the backyard of the Corrigan home:

There’s the well-documented satire in all of Saunders’s work, but the satire found in his third collection, In Persuasion Nation, feels different, partly because the subject being satirized is more often separate from the characters. Below is a passage from “Brad Corrigan, American,” a story set in a metaphysical sitcom world in which Brad is in danger of being written out of the show for his empathy toward a group of speaking corpses, who were killed in an act of genocide and have now appeared inexplicably in the backyard of the Corrigan home:

Animal-rights activists have expressed concern over the recent trend of spraying live Canadian geese with a styrene coating which instantaneously kills them while leaving them extremely malleable, so it then becomes easy to shape them into comical positions and write funny sayings on DryErase cartoon balloons emanating from their beaks, which, apparently, is the new trend for outdoor summer parties. The inventor of FunGeese! has agreed to begin medicating the geese with a knockout drug prior to the styrene-spray step. Also, the pentagon has confirmed the inadvertent bombing of a tribal wedding in Taluchistan.

Similar to the passage from Jeffrey, this begins with an innocuous and familiar register, the language of our ceaseless newsroom. The phrase “expressing concern” is mild, hardly an act of revolutionary protest, which makes the cruel act that the geese suffer so unexpected. Saunders builds on the image, introducing a technical phrase “styrene coating,” and then a strange adjective: “malleable.” Have we ever heard of a goose being covered in styrene coating? Or that a desirable feature of a goose is malleability? Rather than merely linking these unusual set of

words through a list—and they are unusual: “DryErase,” “cartoon,” “emanating,” “parties”—Saunders develops the image in the manner of a narrative, a sequential unraveling. It’s the narrative progression that maintains the newsroom tone, letting Saunders compound the satirical details with the ability to make a sharp cutaway at any moment, a convention of televised reporting.

But it’s the “also” that makes this passage—the abruptness, the surprise. The adverb plays down what is to follow, establishes the future noun as forgettable. The same type of glibness in the documentation of the event recurs in how the pentagon frames it: “an inadvertent bombing.” This is not only a satire of the institutions themselves but of their obfuscatory language—satire by way of mimicry.

Structurally, In Persuasion Nation is unlike any other Saunders collection. It features four sections grouped thematically, each opening with a fictional epigraph from a fictional textbook promoting American imperialist maxims. The colloquial registers that are a fixture in earlier stories here appear fractured, spoken by those who are confused, mumbling, unable to find the words for what they feel.

*

Moving to the collection that Saunders might be best known for, Tenth of December, we find a comedy focused again on the plight of a single character. See the below from a passage in “Al Roosten”:

Moving to the collection that Saunders might be best known for, Tenth of December, we find a comedy focused again on the plight of a single character. See the below from a passage in “Al Roosten”:

There had been that period in junior high, yes, when he had been somewhat worried that he might perhaps like guys, and had constantly lost in wrestling because, instead of concentrating on his holds he was always mentally assessing whether his thing was hurting inside his cup because he was popping a mild pre-bone or because the tip was sticking out an airhole, and once he was almost sure he’d popped a mild pre-bone when he found his face pressed against Tom Reed’s hard abs, which smelled of coconut, but, after practice, obsessing about this in the woods, he realized that he sometimes popped a similar mild pre-bone when the cat sat on his groin in a beam of sun, which proved he didn’t have sexual feelings for Tom Reed, since he knew for sure he didn’t have sexual feelings for the cat, since he’d never even heard that described as being possible. And from that day on, whenever he found himself wondering whether he liked guys, he always remembered walking exultantly in the woods after the liberating realization that he was no more attracted to guys than to cats, just happily kicking the tops off mushrooms in a spirit of tremendous relief.

Here Saunders satirizes the absurd masculine impulse to not only be heterosexual but to constantly justify one’s heterosexuality, and he accomplishes this with a flashback from the story’s protagonist. There’s a casual loquacity in the language—and throughout the collection as a whole—that contributes to what’s so funny. It starts with that “yes” that shakes the progression of the sentence, then continues when we learn of the “pre-bone,” the word “thing” being used to describe his penis, the unfortunate pain of its “tip.” We laugh at the repetition of a funny word, “pre-bone,” and in how its cause changes from Tom Reed to a cat. Further, its repetition shows Al’s obsession, his worry, a comedy steeped in its character. Notice too that just like the cause of the pre-bone changes, so does the location. Saunders’s comedy is located in the physical world: we transition, for instance, from a wrestling match to a scene where a cat is not just “on his groin,” but on his groin “in a beam of sun.” The third-person narration pulls directly from Roosten’s available language system, and the “beam of sun” is funny for how it suggests something deserving of a spotlight, an absurd situation combined with the elementary poeticism belonging to Roosten, who could describe the general sunlight but instead shapes the light into a “beam.” It’s the same when we learn that Roosten is worrying about this “in the woods.” We’re in his head while he’s in a place that tells us more about how he feels—in this case, a need for solitude, for being in the truth of nature. Imagine Thoreau contemplating the ambiguous sources of his “pre-bone.” Saunders wants us to compare Roosten’s futile wrestling techniques to the pitiful strength he shows by “happily kicking the tops of mushrooms,” eliminating phallic objects likely in other beams of sun. To use a Saunders’s word, it’s a relentless “escalation” of the comedic.

There’s also an absurd logic at play in this passage. We see it in the words “because” and “since,” as well as their repetition, which suggests a continual reaching for a truthful conclusion. Similar to how the Brad Corrigan passage generates comedy through the compounding, shifting registers that form a sense of narrative, here Roosten, in the process of justifying his heterosexuality to himself, creates comedy through the evidence he cites: the impossibility of desiring a cat sexually—something he also tries to justify by citing that “he had never even heard that described as being possible.” The “never even” brings us back to that casual register, and rather than claiming on his own the impossibility of desiring a cat, he supports the claim with the fact that other people have not mentioned this to him.

We finish definitively with the language of storytelling. “And from that day on” is how we might expect a fairy tale to end, which is why it’s so funny that instead this is the story of a man justifying his heterosexuality, a story he will apparently return to again in the future.

What I think might be most important here, though subtle, are the brief digressions. In general, Saunders relies little on digression for comic effect. His stories are tight, plot-driven; all the language contributes to some forward motion. While the logic of the comedy might be what defines the humor in Tenth of December, it’s those moments when we receive the full name of the boy inducing the pre-bones, “Tom Reed,” and the subordinate clause that qualifies his abs, which “smelled like coconut,” that are funny despite slowing down the progression of the sentence. These are hardly perceptible digressive twitches, but they foreshadow part of the comedic shift in Liberation Day.

*

Similar to Pastoralia, Saunders’s new collection opens with its longest story, the titular “Liberation Day.” The premise feels like a combination of Tenth of December’s “Semplica Girl Diaries” and “Escape From Spiderhead”: through the limited perspective of a man who is “Pinioned” to a wall with others, memory erased, connected to a machine that allows his owner, Mr. U., to generate entertaining fictional stories from earlier centuries, we find Saunders cranking the dials on his unusual sound. Here is a passage that takes place when the “jamming” Mr. U., after leading several rehearsals, has the speakers perform for his guests:

Lauren goes first, Speaking of her City (arranged N/S along river, Hunger, Raining, Exaltation) in one long sentence. Mid-way through, Craig joins in, Speaking of his City in iambic pentameter: arranged E/W, no river, white, Winter, overrun by oats. Then, with Lauren and Craig still Speaking, I join, and Speak of my City (Sad, Summer, green-blue, arranged N/S along river, blue-green canoes oriented toward the celebration island like magnet needles, the lucky shopkeepers and workers dreamily trailing their hands behind in the cool, clean water, as, with fireworks bursting overhead, they are rowed past the orange-brown cafes toward the one bastion of happiness in their disappointing lives).

As in other stories, Saunders finds a comedic conceit that allows him to focus on language itself. The characters are used by Mr. U. for entertainment, and those imprisoned want to deliver admirable performances. The source becomes the material, the referent the signifier. But the passage is representative of a newer move for Saunders, one he introduced in his novel Lincoln in the Bardo: a polyphonic clash that creates forward motion and comedy through its alternating speakers. Unlike Bardo, though, where characters might politely switch between their monologues in a nineteenth-century register, in “Liberation Day” Saunders has each description mimicked by one controlled voice, a character who is then able to create humor through how he chooses to represent what the others say.

As in other stories, Saunders finds a comedic conceit that allows him to focus on language itself. The characters are used by Mr. U. for entertainment, and those imprisoned want to deliver admirable performances. The source becomes the material, the referent the signifier. But the passage is representative of a newer move for Saunders, one he introduced in his novel Lincoln in the Bardo: a polyphonic clash that creates forward motion and comedy through its alternating speakers. Unlike Bardo, though, where characters might politely switch between their monologues in a nineteenth-century register, in “Liberation Day” Saunders has each description mimicked by one controlled voice, a character who is then able to create humor through how he chooses to represent what the others say.

From Jeremy, we learn of Lauren’s river through the uncommon grouping: “Hunger, Raining, Exaltation.” The summary of Craig’s story begins with an internal rhyme: “river, white, Winter”—but Saunders disrupts the pattern with the detail that Craig’s river area was “overrun by oats,” to form the referenced iambic pentameter. The oats image Saunders could summarize by using the single capitalized word, “Oats,” but instead he has Jeremy end the sentence on a phrase that defies the expectation raised by the prior objects of the list. We then finish on Jeremy’s crescendo, the longest and most extravagant river description, which is again contained in parentheses. Saunders begins with “Sad, Summer,” a stage setting that immediately creates friction. We get the compound modifier to describe the water in “green-blue,” which is then reversed to describe the canoes, a technique that signals the comic intentions of the lyricism in the manner of a Seinfeldian stare. Jeremy ends below a literal explosion of fireworks with a telling metaphor: “one bastion of happiness in their disappointing lives.” The comedy here comes from the excess, the mid-evil word, “bastion,” and the quick shift from happiness to disappointment.

Notice how essential the digressive material is to the passage. All of the comedy turns on the information in the parentheses—without this, we only have the factual, and Craig. I’m not suggesting that “Liberation Day” is different because Saunders uses a certain kind of punctuation, or even that this is the first time he has used digressive comedy, but instead that here the digressive feels more significant in its space and function.

There is another layer in how the narrator seems to be, perhaps unconsciously, referring to his own situation: “one bastion of happiness in their disappointing lives.” It’s a phrase that might easily apply to the imprisoned Jeremy who is determined to please his jailer. But now the language operates on two levels: to entertain and to reveal the interior life of the speaker—an interior life that, at present, seems unaware of its sadness. The comedic effect in the “Liberation Day” passage is notably different from others: there’s nothing slapstick in the above, nor is there a sense of social satire. It’s not laugh out loud sort of funny. Much like Kafka’s shrinking hunger artist, much like Beckett’s Krapp, the dark humor comes from despair.

Earlier Saunders characters often arrive at a state of transcendence through death—obtaining an otherworldly ability to leave behind their material conditions. For instance, the narrator of “CivilWarLand in Bad Decline,” once he is murdered, becomes a ghost with “perfect knowledge.” In “Escape from Spiderhead,” our narrator departs his body when he chooses to kill himself in order to spare other prisoners, breaking through the roof and vanishing into the sky. But in Liberation Day, there is no escape built into the plot. Instead, characters find reprieves from suffering in the same way a writer might: by retaining a private comedic language.