Shadows of Reality, the extraordinary new catalogue of W.G. Sebald’s photographic materials—the first-ever volume of the writer’s images—is an improbable book. In 2004, while working as the curator of photographic collections at the University of East Anglia’s Sainsbury Center of Photography and Art History, Nick Warr, one of the editors of the catalogue, stumbled upon a small Ilford photographic box faintly labeled “Sebald” in pencil, which contained a few handwritten notes and various black-and-white photographs. A few years later, Warr was introduced by chance to one of Sebald’s old friends, Clive Scott, a professor of European literature. Warr invited Scott to take a look at the Sebald box, and as they studied the material, they realized the photographs were in fact the original prints made for Sebald’s books. The accompanying notes were written by Michael Brandon-Jones, the photographer based in the university’s art history department. Decoding them, writes Warr, was difficult and time-consuming, but doing so led to his most significant discovery: the 35mm film negatives Brandon-Jones made in collaboration with Sebald for all of his published work. Shadows of Reality is a testament to this critical but little-known creative partnership.

Readers of Sebald’s major prose works—Vertigo (1990), The Emigrants (1991), The Rings of Saturn (1995), and Austerlitz (2001), in which a melancholy narrator wanders empty cities and ruined coastlines, listening to the people he meets along the way—are familiar with the black-and-white photographs intertwined with his fictional text, an aspect of the writer’s form that he was often asked to discuss in interviews. He would talk of the strong psychic pull of photographs, especially pictures that the viewer has no connection with, which draw him out, so to speak, said Sebald, from the real world into an unreal world; that is, a world of which one doesn’t exactly know how it is constituted but of which one senses that it is there. “These photographs asked to be looked at, challenge us to take them into account,” writes Scott in “Writing With Photographs,” an essay in the catalogue. To Sebald, they were signs that pointed to a world he felt but couldn’t see—where the dead have not really died—a metaphysical feeling he wanted his books to be imbued with. Sebald suggested as well that pictures, unlike narratives, lift one out of time, offering the reader a brief reprieve from the end toward which a text always moves. But these cryptic responses, many of which are included in the catalogue, provide no definitive statement on the purpose of his images. Understanding how the images were made, however, “is not such a speculative task,” writes Warr in “A Small History of Rephotography,” his conversation with Michael Brandon-Jones.

Readers of Sebald’s major prose works—Vertigo (1990), The Emigrants (1991), The Rings of Saturn (1995), and Austerlitz (2001), in which a melancholy narrator wanders empty cities and ruined coastlines, listening to the people he meets along the way—are familiar with the black-and-white photographs intertwined with his fictional text, an aspect of the writer’s form that he was often asked to discuss in interviews. He would talk of the strong psychic pull of photographs, especially pictures that the viewer has no connection with, which draw him out, so to speak, said Sebald, from the real world into an unreal world; that is, a world of which one doesn’t exactly know how it is constituted but of which one senses that it is there. “These photographs asked to be looked at, challenge us to take them into account,” writes Scott in “Writing With Photographs,” an essay in the catalogue. To Sebald, they were signs that pointed to a world he felt but couldn’t see—where the dead have not really died—a metaphysical feeling he wanted his books to be imbued with. Sebald suggested as well that pictures, unlike narratives, lift one out of time, offering the reader a brief reprieve from the end toward which a text always moves. But these cryptic responses, many of which are included in the catalogue, provide no definitive statement on the purpose of his images. Understanding how the images were made, however, “is not such a speculative task,” writes Warr in “A Small History of Rephotography,” his conversation with Michael Brandon-Jones.

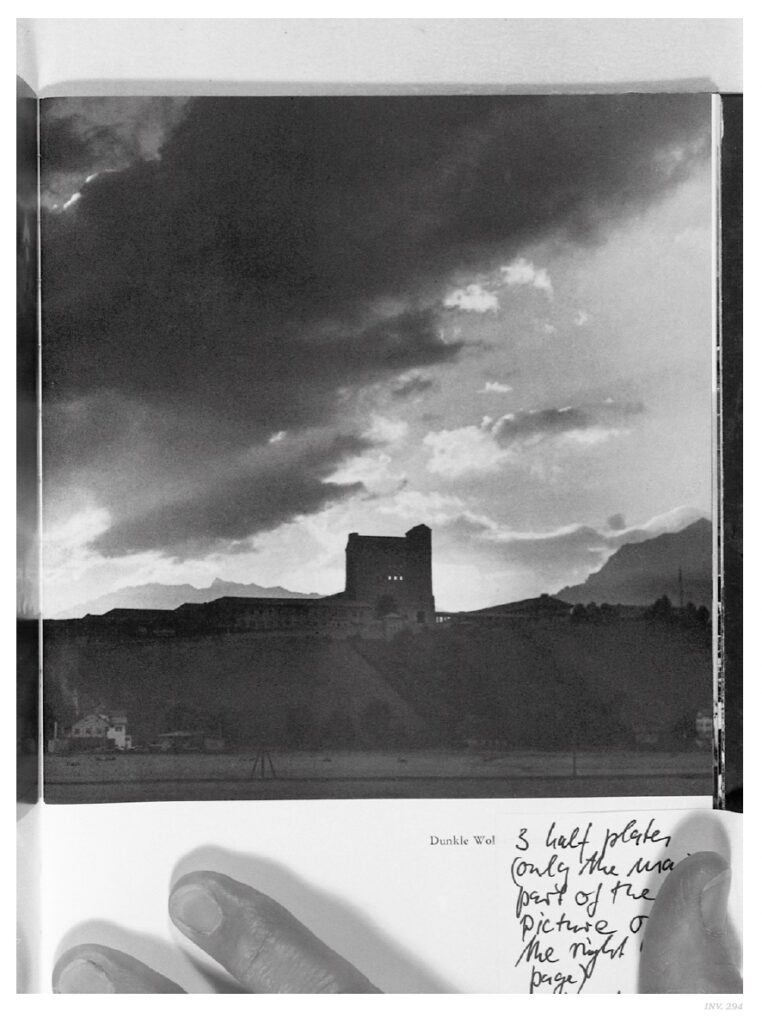

It would begin with a brief meeting in Brandon-Jones’s office (the same office that Nick Warr now occupies). On his visits to the Sainsbury Centre, Sebald would bring Brandon-Jones a pile of material—some snapshots he made, but mostly images from library books, microfilm, postcards, photocopies, 16mm movie film, receipts, and found photographs from family albums and junk shops—and together the writer and photographer would look at each image in turn. “The image of W.G. Sebald surveying the liminal locales of a desolate East Anglia through the viewfinder is an appealing one,” writes Warr, “and one that persists in the imagination of many of his readers,” but this image belies “the multifarious nature of Sebald’s images.” The catalogue goes on to correct misunderstandings of Sebald’s creative process. For instance, while the term “Sebaldian” has come to reductively refer to black-and-white, unpeopled landscapes, his photographic archive reveals a great diversity of visual material. Sebald’s often-cited method of using a photocopier to intentionally degrade photographs, far from a dominant practice, only occurs in a few of his images, and while he did doctor some images—most famously the picture of a book burning that appears in the Max Ferber section of The Emigrants—this, too, is a rarity in Sebald’s archive. Much more important to Sebald, the catalogue shows, was rephotography—the photographing of photographs—which was performed by Brandon-Jones in the darkroom, producing copy negatives and, finally, the black-and-white prints that appear in Sebald’s books.

By rephotographing the diversity of material Sebald brought to him, Brandon-Jones played a critical role in helping the writer, who was never involved in the printing process, achieve a tonal consistency (which Sebald described as a “leaden” quality) between text and image. This was crucial to creating the feeling, in the books, of entering an in-between world where there exists no separation between the living and the dead, time and space, past and present. “The dead are always coming back to us,” says Henry Selwyn in The Emigrants. Later in the same book, Max Ferber, who believes there is neither a past nor a future, feels an odd sense of brotherhood with Wittgenstein after living by chance at a house where the philosopher once lodged. In The Rings of Saturn, during a visit at the home of his friend, the writer Michael Hamburger, Sebald’s narrator has the eerie and inexplicable sense that Hamburger’s desk had once been his own—that Hamburger’s glasses, his piles of papers, all of it had belonged to him. And Austerlitz, in Sebald’s last book, expresses the wish that runs through all of Sebald’s works: “the hope that time will not pass away, has not passed away, that I can turn back and go behind it,” says Austerlitz, “and there I shall find everything as it once was.” Brandon-Jones’s darkroom task, then—even if Sebald’s instructions remained focused on practical concerns to crop this image, darken that one—was to somehow make the photographs appear to have come from the same mysterious source. Rephotographing distanced the images from the moments of their making and remade them as pictures from a single camera-consciousness. Even the snapshots that first came from Sebald’s camera, once they were transformed by Brandon-Jones, looked like the photographs Sebald found in junk shops and family albums. His authorship had been erased, along with the time it was made, unsettling chronology and reinforcing the uncanniness that is a hallmark of Sebald’s books.

In “Writing With Photographs,” Clive Scott suggests the images act as an under-layer of the text, floating to the surface at irregular intervals, such as the otherworldly picture in The Emigrants of abandoned buildings along a canal in Manchester, which interrupts the text as if the image flickered for an instant in the narrator’s mind—a message from inner life—before fading to make room for more words. The catalogue shows the snapshots Sebald made on this walk, but he didn’t use them in the text, and one can see why: they show surfaces. Only the otherworldly photo of the canal, fine-tuned by Brandon-Jones in the darkroom, reveals the narrator’s sense of a deeper world. If we go with this reading of Sebald’s images as messages from below, it is as if Brandon-Jones and Sebald, through the alchemy of their collaboration, co-created glimpses of the narrator’s unconscious, an idea supported by Scott’s claim that the photographs (camera-consciousness) and text (human-consciousness) show intertwined but independent modes of attention. Scott quotes from John Berger’s preface to Steve Pyke and Timothy O’Gray’s I Could Read the Sky: “And so they work together, the written lines and the pictures, and they never say the same thing. They don’t know the same things, and this is the secret of living together.” Similarly, in Sebald, the collisions of text and image produce a mysteriousness that neither could have achieved on their own.

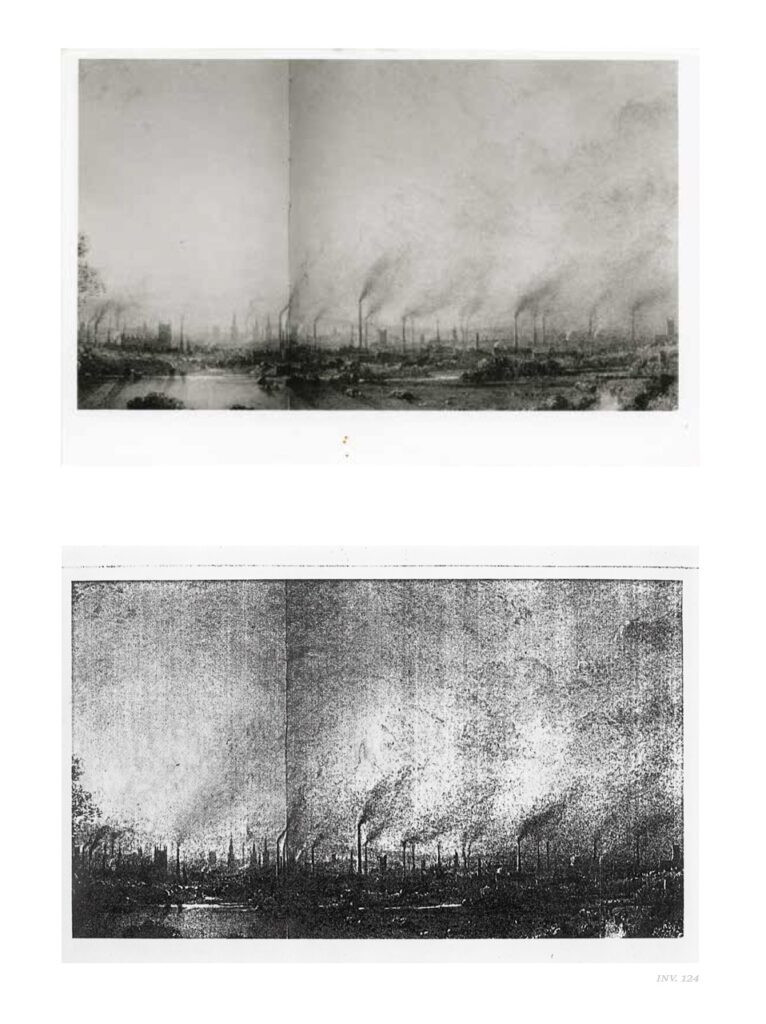

The same is true of Sebald’s practice with Brandon-Jones, which made the writer’s images possible. And there are multiple examples of Brandon-Jones’s role going beyond the technical, such as the degraded, monochrome reproduction of William Wyld’s painting of Manchester in The Emigrants. Taken from Mark Girouard’s 1985 book, Cities & People: A Social and Architectural History, Brandon-Jones experimented with several exposures in an attempt to hide the gutter between the pages, until Sebald gave him a photocopy of the painting for Brandon-Jones to photograph. “I do not think I told Max [Sebald],” said Brandon-Jones, “but in order to soften the appearance of the dark vertical line, which is actually the centre-fold of the book, I remember using a pencil to darken parts of the sky and the smoke.” This freedom to manipulate the image toward what Brandon-Jones understood Sebald wanted to achieve—along with Sebald’s request, during their last project together, that Brandon-Jones photograph an office at the Sainsbury Centre that would appear in the fictional text as the office of Austerlitz—is a testament to the trust and comfort that marked their working relationship. Brandon-Jones’s approach to photographing the office reveals his sensitivity to Sebald’s vision. “The furniture and everything you can see in the picture was exactly as I found it,” he said. “Nothing was rearranged specially for the photograph.” This reads like an echo of The Emigrants’ Max Ferber, who, writes Sebald, “once remarked casually, that nothing should change at his place of work, that everything should remain as it was, as he had arranged it, and that nothing further should be added but the debris generated by painting and the dust that continuously fell and which, as he was coming to realize, he loved more than anything in the world.”

The same is true of Sebald’s practice with Brandon-Jones, which made the writer’s images possible. And there are multiple examples of Brandon-Jones’s role going beyond the technical, such as the degraded, monochrome reproduction of William Wyld’s painting of Manchester in The Emigrants. Taken from Mark Girouard’s 1985 book, Cities & People: A Social and Architectural History, Brandon-Jones experimented with several exposures in an attempt to hide the gutter between the pages, until Sebald gave him a photocopy of the painting for Brandon-Jones to photograph. “I do not think I told Max [Sebald],” said Brandon-Jones, “but in order to soften the appearance of the dark vertical line, which is actually the centre-fold of the book, I remember using a pencil to darken parts of the sky and the smoke.” This freedom to manipulate the image toward what Brandon-Jones understood Sebald wanted to achieve—along with Sebald’s request, during their last project together, that Brandon-Jones photograph an office at the Sainsbury Centre that would appear in the fictional text as the office of Austerlitz—is a testament to the trust and comfort that marked their working relationship. Brandon-Jones’s approach to photographing the office reveals his sensitivity to Sebald’s vision. “The furniture and everything you can see in the picture was exactly as I found it,” he said. “Nothing was rearranged specially for the photograph.” This reads like an echo of The Emigrants’ Max Ferber, who, writes Sebald, “once remarked casually, that nothing should change at his place of work, that everything should remain as it was, as he had arranged it, and that nothing further should be added but the debris generated by painting and the dust that continuously fell and which, as he was coming to realize, he loved more than anything in the world.”

If the catalogue is a testament to Sebald’s collaboration with Brandon-Jones, it is also an example of what Sebald’s biographer, Carole Angier, identified as one of the writer’s major themes: ”the consolations of fellowship through the years.” While reading Shadows of Reality and looking through Sebald’s pictures and Brandon-Jones’s contact sheets, trying to imagine what their day-to-day relationship was like, I kept thinking of images of companionship in Sebald’s books. Above all, I thought of the narrator’s visit, near the end of The Rings of Saturn, to the studio of Thomas Abrams, who had been working for decades on a scale model of the Temple of the Jerusalem. As the narrator takes his leave, Abrams offers to drive him to Harleston, his next destination. “We spent the quarter of an hour to Harleston,” writes Sebald, “sitting side by side in the cab of his truck, and I wished that short drive through the country would never come to an end, that we could go on and on, all the way to Jerusalem.” It is, at root, the same thing Sebald did for 11 years with Brandon-Jones. Side by side, they co-constructed a view.