There was much to do after my father died last year, following a prolonged bout with blood cancer. Not just the funeral arrangements but the other logistical matters: ridding my parents’ house of medical supplies, sorting through financial documents. My older sisters immediately set to work, diligently organizing and discarding things at the house in New Jersey where my parents had retired. But I was in no rush to clean out anything. I particularly didn’t want to dismantle my father’s book collection.

Some girls learn from their dads how to play softball or the art of fly-fishing. I absorbed from mine the power of words. He and I were quite alike, which made at times for a tempestuous rapport, but I mainlined his love of reading and the intensity with which he approached language. After he died, I began to gather some of his books as if to compile a syllabus of my own personal course of grief. Already among my prized possessions were his four-novel F. Scott Fitzgerald set, a 1945 anthology of British and American poetry that I filched from him a few decades ago and his Richard Ellmann biography of James Joyce. Growing up, I used to spend hours in the basement of our Long Island home gazing at the spines of his hardbacks: Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar, For Whom the Bell Tolls by Hemingway, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s Gulag Archipelago.

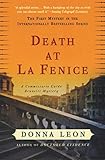

An engineer by training and vocation, my father had a deep interest in science. But he was also a perennial student, a music lover and world traveler. Hence the books I’ve been reading span the gamut from Oliver Sacks’s The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat to Andrew Hodges’s 1983 biography of Alan Turing and Donna Leon’s Guido Brunetti novels. I’ve also revisited books he had insisted I read when I was younger—including such questionable fatherly suggestions as Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer. I was in high school when he suggested I read the book, which had been controversial for its provocative descriptions of sex and was banned until 1961, the year my father turned 25. The recommendation was characteristic of a man who dared me to wear two different shoes to school for a week.

An engineer by training and vocation, my father had a deep interest in science. But he was also a perennial student, a music lover and world traveler. Hence the books I’ve been reading span the gamut from Oliver Sacks’s The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat to Andrew Hodges’s 1983 biography of Alan Turing and Donna Leon’s Guido Brunetti novels. I’ve also revisited books he had insisted I read when I was younger—including such questionable fatherly suggestions as Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer. I was in high school when he suggested I read the book, which had been controversial for its provocative descriptions of sex and was banned until 1961, the year my father turned 25. The recommendation was characteristic of a man who dared me to wear two different shoes to school for a week.

When my father died a year ago, at age 85, he had been seriously ill for nearly two years. But before he got sick, what he said about books—and what he modeled by faithfully returning each week from the public library in our town with a stack of books—furnished me with a modus vivendi, no matter the job I hold. In the wake of his death, I wanted to reflect on who he had been, and what he had imparted to me. And I’ve spent much of the past year doing that by reading his books.

During the final year of his life, however, he didn’t read almost at all, and all his forceful enunciations and bold proclamations about literature came to a halt. As is common with those who suffer from multiple myeloma, he simply faded away, after a life of traveling overseas and an engineering career that began with work on the Apollo space missions’ lunar excursion module (he also supervised, often sternly, four daughters). Hence our days of debating ideas were over—before I was ready. Before I’d properly telegraphed the immensity of his influence or, quite candidly, before I gave him the satisfaction of admitting as much. I concluded too late that he might have been the most interesting man I had ever known up close.

If while my father was alive I was obsessed with what he said, I am now obsessed with his belongings. Whenever I’ve visited my parents’ home in the past year, I’ve always spent some time suspended before his bookcases. His books attest to a vigorous curiosity. He had dozens of hefty coffee table art books on the Italian Renaissance, Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, and Abstract Expressionism, plus monographs of Rembrandt, Leonardo Da Vinci, Canaletto, Degas, Giacometti, and Marino Marini; biographies of Jazz greats like Duke Ellington and histories of this American musical genre, one that inspired in him a fanatical devotion; scientific treatises and engineering books, with titles like Selected Papers on Quantum Electrodynamics. Everywhere I looked I saw the story of his life.

If while my father was alive I was obsessed with what he said, I am now obsessed with his belongings. Whenever I’ve visited my parents’ home in the past year, I’ve always spent some time suspended before his bookcases. His books attest to a vigorous curiosity. He had dozens of hefty coffee table art books on the Italian Renaissance, Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, and Abstract Expressionism, plus monographs of Rembrandt, Leonardo Da Vinci, Canaletto, Degas, Giacometti, and Marino Marini; biographies of Jazz greats like Duke Ellington and histories of this American musical genre, one that inspired in him a fanatical devotion; scientific treatises and engineering books, with titles like Selected Papers on Quantum Electrodynamics. Everywhere I looked I saw the story of his life.

One of the first books of his that I sought out was the biography of Turing, the British mathematician who during World War II devised a machine that helped crack the so-called “Enigma” cyphering code the Germans used to encrypt their communications. I can remember the year my father asked my mother to get it for him for Christmas, and the trouble it caused her. There was no way to look it up online—no large central book emporium—and even telling the title to my mother didn’t guarantee anything. (My parents had constructed personas whereby he was the smart one and she was his ditzy foil. The reality was quite different; she not even a little ditzy.) Nevertheless, having searched bookstore after bookstore, she found it, and I recall many conversations that December where she half-joked that finding this book about Turing was itself an enigma.

Underlying the story of the British genius who helped break German code, is the notion that Turing the man was an enigma. And as a contrarian and someone who relished disagreement, my father was interested in enigmas. The book doesn’t stint on mathematical theory or the marathon technical fine-tuning required to crack the code, which my father must have loved. Turing, a forefather of modern computing, comes across as a singular figure—brilliant, determined, unswayed by popular opinion—and his story singularly tragic. Despite his wartime service, he died with a criminal record, having been convicted by British authorities of the crime of homosexuality. As noted by author Andrew Hodges, he was hounded to death.

The book was originally kept in that Long Island basement of long ago, where I’d also spied Gulag Archipelago countless times. At 650 pages, it took up a lot of shelf space, and in years past, Solzhenitsyn’s exposé on the Russian penal state long before the fall of the Iron Curtain had proved too formidable for me. What struck me this year as I began reading my father’s 1973 hardback edition in earnest was the paragraph from the author right on the front cover, as if the urgency of his message forces him to begin relaying it before you even open the book. The dissident, who dedicated his book to “all those who did not live to tell it,” gives the first chapter a simple, ominous title: “Arrest.”

The book reminds me of the history witnessed by those born, like my father, in the 1930s. It’s a bitter irony I’ve only tackled this book now that I cannot ask him about it: Traveling for his work at a government laboratory, he visited Russia a dozen times during the final years of his career. As I read, I thought about how much I wish I had borrowed this book while he was alive—a sentiment I felt as I read many of the other books on his shelf. Like the claw in a carnival game, my mind grasps at shards of his comments about the book, without being able to fully retrieve what he said.

Those myriad visits to Russia that began when he was in his sixties would have perhaps wearied another man. But my father, who was born in Bayonne, New Jersey, a short distance from the port where his grandfather had worked and across the Hudson River from glittering Manhattan, loved to travel. When I lived in Florence after college as an expat, my father visited me twice, the first time as a stopover on his way home from Russia. Brunelleschi’s churches there delighted him. But the Italian city he loved the most was Venice. He fanned this obsession by having marble tiles with scenes of Venice installed in their kitchen, and by reading Donna Leon mysteries featuring Commissario Guido Brunetti.

As with many things my father recommended, I had ignored his advice to check out the Brunetti series, dismissing the books as simple mysteries by an American that didn’t interest me and which were, besides, written in English. Then, stumbling on a nonfiction book by Leon called My Venice and Other Essays on his shelf, I discovered a striking understanding of how men and women relate in Italy, plus observations about the presence of water and corresponding absence of cars that Leon argues defines the city of Venice. I am now reading one work from the Brunetti series whose title alone delights me: Acqua Alta (literally high water, the phrase used in Venice for the days when the canals flood).

As with many things my father recommended, I had ignored his advice to check out the Brunetti series, dismissing the books as simple mysteries by an American that didn’t interest me and which were, besides, written in English. Then, stumbling on a nonfiction book by Leon called My Venice and Other Essays on his shelf, I discovered a striking understanding of how men and women relate in Italy, plus observations about the presence of water and corresponding absence of cars that Leon argues defines the city of Venice. I am now reading one work from the Brunetti series whose title alone delights me: Acqua Alta (literally high water, the phrase used in Venice for the days when the canals flood).

Not all the works I’ve been reading belonged to my father; my year of reading him also includes books of my own that his death has inspired me to re-read. One such book: Suspended Sentences by Patrick Modiano. My father had died one cold December night only hours after I’d left his side to return to my home in Connecticut. When I drove back, I headed straight to the bookcase behind my mother’s chair in the living room. I knew I’d left the Modiano novel there, and I needed it back. I needed to immerse myself in the world of a protagonist who’s desperately rummaging through the past to understand how he has arrived at the present moment. As the book’s translator, Mark Polizzotti, noted in an essay for Yale University Press, which published the novel, Modiano’s work harbors “the underlying sense that, no matter what we do, it is never quite good enough to compensate for the disappointments we fear we have inflicted, or that have been visited on us.”

Not all the works I’ve been reading belonged to my father; my year of reading him also includes books of my own that his death has inspired me to re-read. One such book: Suspended Sentences by Patrick Modiano. My father had died one cold December night only hours after I’d left his side to return to my home in Connecticut. When I drove back, I headed straight to the bookcase behind my mother’s chair in the living room. I knew I’d left the Modiano novel there, and I needed it back. I needed to immerse myself in the world of a protagonist who’s desperately rummaging through the past to understand how he has arrived at the present moment. As the book’s translator, Mark Polizzotti, noted in an essay for Yale University Press, which published the novel, Modiano’s work harbors “the underlying sense that, no matter what we do, it is never quite good enough to compensate for the disappointments we fear we have inflicted, or that have been visited on us.”

In the hours after my father’s death, the disappointments plaguing me most were those I inflicted upon him. So one Modiano work wasn’t enough; I also found my way back to his novel So You Don’t Get Lost in the Neighborhood (translated in 2015 by Euan Cameron), about a writer whose address book goes missing. It is found by a mysterious man who alerts him to the discovery only after perusing its entries. At one point, Modiano references “a fragment of reality” he had inserted in an otherwise fictional book, writing that it was like “those private messages that people put in small ads in newspapers and that can only be deciphered by one person.” Clues, in other words. I’ve pored over my father’s belongings as if they were clues, trying to suss out what had eluded me in life. Reading Modiano, one concludes it’s as if we live our childhoods in a dream-like state, and we spend the rest of our lives trying to reconfigure what happened and what it meant. Modiano’s work convinces me that nothing captures our attention—and nothing contains the same degree of intimate, beguiling mystery—as childhood. Hence, perfect reading for the year after my father’s death.

In the hours after my father’s death, the disappointments plaguing me most were those I inflicted upon him. So one Modiano work wasn’t enough; I also found my way back to his novel So You Don’t Get Lost in the Neighborhood (translated in 2015 by Euan Cameron), about a writer whose address book goes missing. It is found by a mysterious man who alerts him to the discovery only after perusing its entries. At one point, Modiano references “a fragment of reality” he had inserted in an otherwise fictional book, writing that it was like “those private messages that people put in small ads in newspapers and that can only be deciphered by one person.” Clues, in other words. I’ve pored over my father’s belongings as if they were clues, trying to suss out what had eluded me in life. Reading Modiano, one concludes it’s as if we live our childhoods in a dream-like state, and we spend the rest of our lives trying to reconfigure what happened and what it meant. Modiano’s work convinces me that nothing captures our attention—and nothing contains the same degree of intimate, beguiling mystery—as childhood. Hence, perfect reading for the year after my father’s death.

Another book I read this year that my father hadn’t recommended but which he would have appreciated: If This Is a Man by Primo Levi. As a part-time translator of Italian literature, I’ve read Levi’s account of his concentration camp internment in both English and Italian. But I first heard about Levi from my father, most likely in 1987 when the master Italian author and chemist died by suicide, four decades after his liberation from Auschwitz. Levi possessed two qualities my father revered: exquisite scientific acumen with an abiding interest in literature.

Another book I read this year that my father hadn’t recommended but which he would have appreciated: If This Is a Man by Primo Levi. As a part-time translator of Italian literature, I’ve read Levi’s account of his concentration camp internment in both English and Italian. But I first heard about Levi from my father, most likely in 1987 when the master Italian author and chemist died by suicide, four decades after his liberation from Auschwitz. Levi possessed two qualities my father revered: exquisite scientific acumen with an abiding interest in literature.

More reading remains for the coming year—several novels by Iris Murdoch and Richard Wright’s Native Son, all of which I plucked from my father’s shelf; my own copy of Brendan Behan’s play The Quare Fellow (whose opening lines magically include the words “that old triangle went jingle jangle,” and also appear on a poster of seminal Irish writers that my father gave to me); as well as some books he successfully pressed upon me with messianic zeal (or overbearing smugness), including the Ellmann biography of Joyce, which so effectively probed the Irish novelist’s tortured relationship with his father—a detail of course impressed upon me by my own father.

More reading remains for the coming year—several novels by Iris Murdoch and Richard Wright’s Native Son, all of which I plucked from my father’s shelf; my own copy of Brendan Behan’s play The Quare Fellow (whose opening lines magically include the words “that old triangle went jingle jangle,” and also appear on a poster of seminal Irish writers that my father gave to me); as well as some books he successfully pressed upon me with messianic zeal (or overbearing smugness), including the Ellmann biography of Joyce, which so effectively probed the Irish novelist’s tortured relationship with his father—a detail of course impressed upon me by my own father.

I have yet to find among his things the cassette tapes I’d often borrowed containing august recitations of classic poems by British narrators. I can still hear the somber voice of the narrator, intoning like a bell tolling the hours this line from Dylan Thomas, one of Dad’s favorite poets: “And death shall have no dominion.”

There are many days when death most certainly has dominion over me, seeing as it has robbed me of my father before I could fully savor his singular, vigorous, sometimes maddening way of approaching life. But as I surround myself with my father’s belongings, and most especially his books, I fight its grip. I’d like to think what will have dominion over me, instead, is this communion with words, which has the force to change our lives. The force to make our lives. And that’s what he imparted to me, what remains with me—along with his books—now that he is gone.