Davis School District in Utah–a 70,000+ district north of Salt Lake City–has officially removed the Bible from elementary and middle schools. This may be the first official removal of the religious text from schools in the country following a district’s review process. The decision comes after a parent complained about its vulgarity and violence. That parent was angry about the district’s previous decisions to remove books like Looking for Alaska and The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian in accordance to Utah’s new sensitive materials law.

In their complaint, they noted the right-wing “parental rights” group Utah Parents United as prompting the creation of the law and the moral panic around books across the state, stating that the group’s pressure was undermining student education and their First Amendment Rights. The parent noted that the Bible was conveniently left off Utah Parents United’s naughty books likes, despite being “one of the most sex-ridden books around.”

The Bible will remain on shelves at district high schools, and an appeal has already been filed over the decision.

Although Utah’s 2022 sensitive materials law (House Bill 372) applied to the novels removed from the district, that was not cited as the reason for the Bible’s removal. Instead, the review committee found passages too vulgar and violent for those younger than high school age. The law allows committees to apply the standards as they see fit, and Davis District has exercised this flexibility several times. This is one of the reasons why such laws remain a concern: the latitude they offer districts means that a committee can make any decision they would like to, however they would like to, without consideration for the value of a text–nor how such decisions infringe on First Amendment Rights of students.

Whether or not the formal complaint filed against the Bible in December was satirical does not matter to the district. They followed the procedure set forth in their policy and treated it as real; the outcome was perhaps not expected.

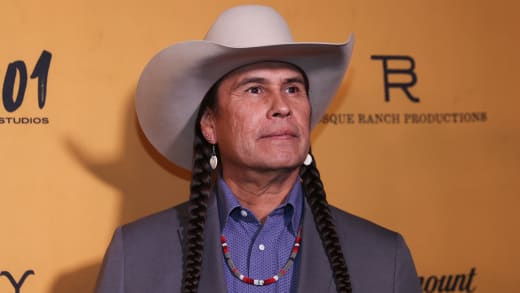

According to KUTV, State Representative Ken Ivory, who supported Utah’s House Bill 372, did not see the removal of religious texts as a problem under the law. Moreover, he does not believe the removal of the book from Davis’s elementary or middle schools constitutes a book ban.

“No, not at all. What we’re looking at is ‘What’s age-appropriate?’ Many people have talked about book bans and this has nothing to do with a book ban. It’s about what’s age-appropriate for children in schools,” Ivory said.

The Bible is not the only religious text under fire in the district, either. Following the decision to remove the book, another complaint came in against the Book of Mormon on Friday. Although the district claims that privacy dictates they cannot disclose who the complaint came from nor what it contains, chances are that information will emerge in the coming weeks, thanks to the legal precedent of the Freedom of Information Act. The information about who creates a challenge and what they object to is not subject to nondisclosure, despite the district’s claim.

In the last year, several districts have faced challenges of the Bible, most done as a response from parents and activists who find the book review process and vague language around “inappropriate materials” applies to the religious text. Among the districts which have pulled the Bible include Keller Independent School District (TX), where it was returned to shelves and Escambia Schools (FL), where the state law has included language that specifically addresses the educational value of the Bible and thus, will not allow it to be banned. Escambia is currently being sued by PEN America, Penguin Random House, and several authors and creators over their book banning decisions.

Individuals have proposed challenges to the Bible across schools, too, in hopes of making a point about these laws. Those challenges, however clever they may seem, run counter to the pillars of the anti-censorship movement and instead create an opportunity for individuals to get a few minutes of fame about their behavior, rather than point directly to how book bans–”cleaning up books” or “curating collections,” in the parlance of censors–are antithetical to the First Amendment.

The banning of the Bible is not a win for anti-censorship, nor is it worth celebrating in any capacity. You don’t end book bans by banning books, even in jest. In fact, as Davis Schools show, you only end up banning more books.