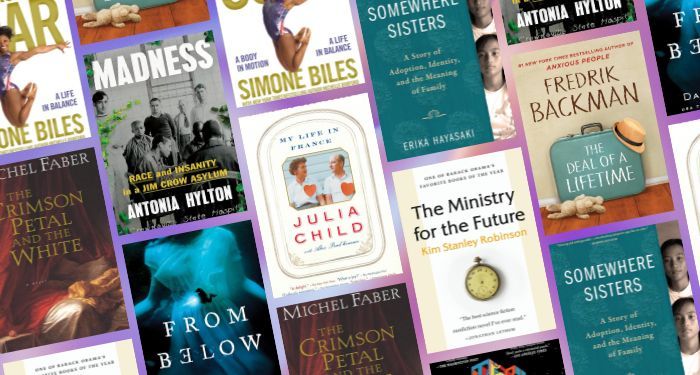

In my twenties my mother foisted on me a slim book titled Gift From the Sea by Anne Morrow Lindbergh and told me it was essential to a woman’s life. Not this woman, I’d thought—a business school graduate soon to start my own enterprise, a young woman certain she knew everything there was to know of the world. I gave the book a patronizing glance—many of the chapters were named after seashells—stuck it on a bookshelf and forgot about it.

Forty years later I’m enrolled in a program of spiritual direction, learning how to counsel people to connect to their deepest longings—and in the process, my own. I’m sitting at my desk, devouring an article by Reverend Walter Burghardt titled “Contemplation: A Long Loving Look at the Real.” He writes of mystics, social workers, philosophers who know how to engage this “long loving look.” Touch these people, he says, “and you will touch the stars.” One name he mentions in the article astonishes me: Anne Morrow Lindbergh. He references what he calls her “counterculture conviction” as expressed in Gift From the Sea—she writes that she must have her “hour to be alone.”

Gift From the Sea! The book my mother loved and that I’d scorned. I scour my shelves to no avail. I determine to find it. Finally, I spot it on a shelf at my mother’s house. I leaf through pages hoping to find some trace of what my mother thought or felt as she read, but not one sentence is underlined or starred, there are no notes in the margins—only a small, faded piece of paper torn from a notebook tucked inside. I wedge the paper deeper, close the book, and stow it in my bag to bring home to read.

*

Lindbergh had the type of pedigree my mother appreciated—daughter of the U.S. ambassador to Mexico and a Smith College graduate with wealth, literary aspirations and accomplishments, and a dashing husband, Charles Lindbergh, the aviator famous for flying solo across the Atlantic. She began Gift From the Sea in 1950 and published it in 1955, at the age of 49—just a few years younger than my mother when she read it. The book is not linked to actual events or memories. Lindbergh writes for women, though she adds in her introduction that she writes for men too. She writes, she says, to explore the “balance of life, work and human relationships.” I think—yes! I want to know what she knows.

Kurt Wolff, her publisher at Pantheon, called the book “contemplative prose” and discussed with Lindbergh the difficulty of finding a balance between abstract ideas and concrete experiences. Gift From the Sea is a meditation on life, solitude, marriage, family, and womanhood, with a modest, quiet tone that appeals to me, and may have also appealed to my mother, and is certainly in keeping with Lindbergh’s character, raised, as she notes in her diary, “to be a good girl, and to want to please everyone.” Lindbergh recognizes this goal as not only impossible, but also undesirable, while also feeling that “all publishing is indecent exposure.”

She wrote the book on Captiva Island in Florida, staying in a small cottage near the beach, finding freedom there from inhibitions, personal concerns, worldly affairs. Gift From the Sea is mostly ordered by the shells that Lindbergh finds or is given. Each shell’s particular contour, shapes, colors, and purpose suggest to Lindbergh truths upon which to live one’s life. The first chapter begins at the beach, the nexus of my mother’s—and my—longings and memories. Lindbergh stuffs totes with notes to write, mail to answer, books to read, but “the books remain unread, the pencils break their points, and the pads rest smooth and unblemished as the cloudless sky.” Instead, she’s lulled by the ocean’s steady beat; emptying body and mind, she writes, she is open to a “a gift from the sea.” I’m similarly lulled, though I usually manage to finish my books and write in my journal, but my mother must have sensed a kindred soul. How many times did she—really my father, and later me—lug to a beach vacation several totes stuffed with the contents of her desk, most of which she never addressed. On my mother’s last trip before dementia made it impossible to travel, she laid on her bed or on a couch on the porch, happy to be with family, content, she said, “to listen to the waves.”

With the first shell Lindbergh describes, it’s clear she writes from the perspective of the married-with-children and money-in-the-bank set—a world of privilege that she acknowledges in her diary. The channeled whelk she finds is tiny as her thumb with perfect spirals of dull gold climbing to a peak, once home, she imagines, to a hermit crab now fled the nest, as she has. “Had [the shell] become an encumbrance?” She thinks about the shape of her life: five children, husband, messy home in the suburbs, responsibilities for “meal planning, marketing, bills,” school conferences and after-school pick-ups, ferrying children to sports practice, camp in the summer, social arrangements, friendships to maintain, organizations to support. These are concerns for those overwhelmed by abundance, whose closets and home overflows—a world that matched my mother’s, and partly, mine.

Despite her privilege, Lindbergh juggles competing demands that women from many economic strata will recognize. She wants relief from the “circus act we women perform every day of our lives.” She wants to learn “how to remain whole in the midst of the distractions of life.” She wants to find an inner and outer peace, a balance between being alone and being with others. I hear my mother in those wants. Cleaning out her home for a recent move I found a journal she had begun the year after my father died, written in a quiet, interior voice not unlike Lindbergh’s. “Serenity has been important in my life,” my mother wrote, believing that equanimity enabled her to center herself and accept life’s challenges and changes. Perhaps the desire for equanimity was a way for my mother to find balance in a marriage of sharing, love, and friendship that was nonetheless dominated by my father’s extroversion, his “doing” to her “being,” his constant need for her attention and presence.

Likening it to the full and powerful moon, a self-sufficient island, a cat’s eye, Lindbergh discovers a moonshell. The shell’s etched spirals curl to a central, dark point, staring at Lindbergh as she stares back. Everyone, and especially women, “should be alone sometime during the year… each week, each day.” Lindbergh was much alone with the children, her husband rarely sharing his frequent and extended travel plans. Her daughter Reeve, remembering the 1950s, writes “the quality I associate with my father in that era is iron.” She likens iron to his hair color, his sometimes spankings of her and her siblings, his unyielding, stern lectures. In her memoir she says that “some of the time,” when her father was away, her mother, though often lonely, was “just as relieved as we [the children] were.” She notes that at one point in that period her mother told her that if things didn’t improve, she would get a divorce. A. Scott Berg writes in his biography of Charles Lindbergh that some 10 years after Gift From the Sea’s publication, after an illness, Anne finally gave herself permission to establish her own pace and rhythm of life—she never could match that of her husband, she wrote in her diary, though she tried.

Likening it to the full and powerful moon, a self-sufficient island, a cat’s eye, Lindbergh discovers a moonshell. The shell’s etched spirals curl to a central, dark point, staring at Lindbergh as she stares back. Everyone, and especially women, “should be alone sometime during the year… each week, each day.” Lindbergh was much alone with the children, her husband rarely sharing his frequent and extended travel plans. Her daughter Reeve, remembering the 1950s, writes “the quality I associate with my father in that era is iron.” She likens iron to his hair color, his sometimes spankings of her and her siblings, his unyielding, stern lectures. In her memoir she says that “some of the time,” when her father was away, her mother, though often lonely, was “just as relieved as we [the children] were.” She notes that at one point in that period her mother told her that if things didn’t improve, she would get a divorce. A. Scott Berg writes in his biography of Charles Lindbergh that some 10 years after Gift From the Sea’s publication, after an illness, Anne finally gave herself permission to establish her own pace and rhythm of life—she never could match that of her husband, she wrote in her diary, though she tried.

Several key events occurred in Lindbergh’s life in the course of writing Gift From the Sea. In the early fifties she underwent psychoanalysis with John N. Rosen, after which, she told Reeve, “Things got better.” She also deepened her friendship and confidences with Dana Atchley. It’s impossible to know, but not impossible to surmise, that in writing the book she came to an acceptance of time without her husband, realizing its importance to her life as a woman, and as a writer. She coined the phrase “that is my hour to be alone,” to demarcate to others, and to oneself, time specifically for oneself. I heard my mother say many times throughout her life—“this is my quiet time”—words that expressed what may have been hard for her, or perhaps any woman at the time, to claim: personal time, space, privacy. I used to smile at these curious words, but years later adopted versions when asserting quiet time with my children, riding in a taxi, getting a haircut.

Lindbergh’s common oyster shell—unlovely with its irregular shape, smaller shells attached, the uneven, lumpy surface—represents the middle years of marriage, when a couple struggles to “achieve a place in the world,” when families, homes, and livelihoods are built, a stage that represented many years of Lindbergh’s life, with five children, several homes, her, and her husband’s work. My mother never fully relinquished this stage, striving full tilt until dementia to achieve social prominence through accomplishments and her home—an unconflicted ambition for her that I rejected, though felt, at times, as a tension between my inner and outer worlds. The oyster shell eventually gives way with age to the argonauta—lovely, delicate, rare, a base from which to launch one’s final adventure, when a woman and man must meet as “two whole, fully developed people,” an understanding that may have reflected Lindbergh’s desire to define herself outside her marriage and home. Did my mother, in reading Gift from the Sea, discover a way to carve out necessary space from the husband she adored—a larger-than-life entrepreneur who commanded her attention, and that of others, with his presence, his moods, his successes, his advice? Lindbergh concludes that perhaps her most important takeaway from the beach was that every stage of a relationship is in constant flux, like the ebb and flow of the ocean.

*

After Charles’s death in 1974, widowhood may have brought Lindbergh to a further understanding of the ideas expressed in Gift From the Sea. “Woman must come of age by herself—she must find her center alone,” she writes. My mother achieved a fully formed, separate self in widowhood, when she surprised everyone she knew—though probably not herself, and certainly not my sister and me—by going wholeheartedly into life: giving dinner parties, inviting friends to concerts and luncheons, traveling with a museum group. Widowhood strengthened my mother’s voice and presence in the world—no longer an adjunct, but the star.

Lindburgh writes that she composed Gift from the Sea “to work out my own problems.” Indeed her marriage had long been troubled. In 1956, a year after publishing Gift From the Sea, Lindbergh began a years long affair with Manhattan internist Dr. Dana W. Atchley. The following year, Charles started a romance with a German hatmaker, with whom he fathered three children.

And one can only wonder how that most public trauma—the highly-publicized 1932 kidnapping and murder of her infant son—shaped her relationships and her worldview. In the introduction to one of her published volumes of diaries and letters, Lindbergh writes that her life can’t be understood without the kidnapping. The all-encompassing media coverage enveloped them during the search for and discovery of their child’s body, found 10 weeks after his disappearance. Writing in her diary about the instant she learned that her baby was dead, she says, “Everything is now telescoped into one moment—the moment when I realized the baby had been taken and I saw the baby dead, killed violently, in the first flash of horror.” Several years later, the kidnapper was tried, convicted, and executed. Berg writes that Lindbergh never saw her husband cry.

At the start of their relationship Lindbergh writes that her soon-to-be husband admonished her to “never write anything you would mind seeing on the front page of a newspaper.” This had the effect of muzzling her, she writes, and inhibiting her interior life. One result of the tragedy, she concludes, is that “sorrow also played its part in setting me free,” that honesty was preferred to discretion or privacy.

Gift From the Sea makes no mention of the tragedy, in keeping with the style and tenor of the book. However, Lindbergh’s daughter Reeve writes in the introduction to the anniversary edition that every time she reads the book what surprises her is her mother’s “enormous, sustaining strength.” She lost her first child, she was the first woman to achieve a first-class glider pilot’s license, the first woman to be awarded the National Geographic Society’s Hubbard award medal for aviation and exploration adventures, Reeve notes. “To grow, to be reborn, one must remain vulnerable,” Lindbergh writes.

*

In the introduction to the fiftieth-anniversary edition of Gift From the Sea, Lindbergh’s daughter Reeve writes that she reads the book annually, sometimes two or more times a year. After her mother’s death—and in the wake of several public and private revelations about her family—she took the book to Captiva Island in Florida. She was in search of her mother, she wrote, for “her wisdom and her encouragement.”

I read Gift From the Sea for the first time—more than 40 years after my mother recommended it—to find her. I keep returning to “that is my hour to be alone.” My mother lived by those words, she created space and time to dream and imagine, free from her children, from her husband, from her day-to-day. This is the book’s wisdom—this is my mother’s gift to me. I can’t talk with her now though I want to. I don’t know if she’d agree with my reading. There are questions I wish I’d asked her. What she’s left me with is her love for this book, with words that ring true to my memories of her, words that express what she may have had a hard time articulating.

Women, by choice, by divorce, by death, frequently find themselves alone at the end of their lives more often than men. After widowhood and for 10 years before dementia, my mother modeled for me how to live without a man. Perhaps, reading Gift From the Sea, she’d gathered and absorbed the strength she needed over her lifetime to keep her self intact, living with a powerful man, and imagining she may someday live without him. Perhaps she foresaw a day when I might be alone. Perhaps that’s why she wanted to share the book with me.

Gift From the Sea sits on my shelf now, decades later, the corners of its pages turned down, passages underlined and starred, notes in the margins. I wouldn’t have understood it in my twenties anyway.