The Columbia River Bar is the violent meeting of the twelve-hundred-mile-long Columbia River and the Pacific Ocean, the site of over 2,000 shipwrecks. Thirty-three tributaries feed the Big River with rainwater in the ninety miles between the Willamette and the Pacific Ocean, and by late May and early June the flow of the lower Columbia becomes truly stupendous, carrying up to 1.2 million cubic feet of water per second at its mouth.

*

Friday, July 16, 2021

As we lifted our boats off the trailer, the sky was low and gray all the way to the horizon, with only a faint spot of lightening in the south to suggest that the sun was there at all. The air was filled with drizzle and mist, precipitation and evaporation, falling and rising. Lowering my end of the main hull onto a damp patch of mossy grass, I felt a slightly claustrophobic sensation of not just the weather closing in around me but the whole world with it. The scene was so far from what I’d imagined, from the picture in my mind of luminous blue overhead and vivid white caps marking our distant goal, that for the first time I felt doubt slipping in through the cracks in my resolve, and wondered about continuing forward.

For months now, my friend Ray Thomas and I had been talking about the RIGHT DAY to cross the Columbia River Bar. The words had been in quotation marks the first few times we’d used them, but grew into all caps as the concept loomed larger and larger in our thoughts. The venture we had in mind would only make sense, we kept reminding each other, if we found the Right Day.

When I’d first spoken to Ray about “the right day” back in April, I’d been quoting Bruce Jones, who, along with occupying the office of mayor of Astoria, Oregon, served as deputy director of the Columbia River Maritime Museum. In the email in which he introduced himself and suggested we meet at the museum, Mayor Jones had attached a photograph of the astounding turbulence a person might encounter at the place where one of the world’s largest, most powerful, and fastest-moving watercourses spills into the Pacific Ocean. Actually, this intersection of river and sea is more of a slam than a spill—“like two giant hammers pounding into each other,” as the head of the Columbia River Bar Pilots Association described it to the New York Times back in 1988.

*

We knew already that the wind that day was steady at about twenty-two miles per hour, too intense for a bar crossing in a kayak, but neither of us was prepared for what that felt like on a span of the river where the Columbia’s mouth was only a little more than a mile to the west. The wind waves were three and four feet, not coming in sets at intervals of seven to nine seconds like on the ocean, but in an incessant and erratic chop that struck our boat from changing directions as current and tide thrashed against one another. I was in the front position again, and up there I felt more like a buckaroo than a sailor, being tossed not only from side to side but also fore and aft as we passed abruptly over peak and into trough and then onto peak again, and so forth, our heads soaked, gasping in awe. Our sail was full, and we were both pedaling, going at what was probably the trimaran’s max velocity, about seven miles per hour.

I was still too happy to be alive to feel embarrassed, so I smiled back.

After a few moments of being shaken, I felt exhilaration rise in me, and I was grinning crazily, marveling at how well the Hobie absorbed the pounding it was taking, continuously oscillating back to equilibrium, no matter how tilted it was by the waves. We had headed out of the boat basin straight for the buoy that floated in the middle of the river, intent on crossing to the Washington side, a distance of nearly four miles. We got only as far as about a hundred yards from the buoy, though, when Ray, who had the rudder, turned us back to shore.

The wind and our front-to-back positions made explanation difficult, but when I turned to look at Ray, I was pretty certain I saw fear in his eyes. This was perfectly understandable under the circumstances, I knew, but I was disappointed that we hadn’t continued across the river. And I was surprised. I knew Ray as a risk-taker. He had long been unpopular among the wives of various friends and associates, mainly because they believed he was determined to put not only himself but also their husbands into life-threatening situations. It was a reputation that discomfited him even as he cultivated it.

Yet Ray had been circumspect from the first about the idea—my idea—of us crossing the bar in his trimaran, warning me more than once that it would have to be approached in stages that started with building trust that we could work as a team on the water, and then together studying the Columbia Bar in depth and at length before venturing onto it. That was fine. I was already committed to doing the research in order to write this book, and it seemed like an excellent idea for Ray and me to practice in the trimaran for some number of times before taking on the bar. To my growing concern, and even annoyance in a couple of cases, though, Ray had begun to remark that he wasn’t sure about this whole project, that he doubted I understood how dangerous it was, and that it didn’t mean nearly as much to him as it did to me.

*

The park’s launch ramp was used mainly by large recreational fishing boats, though I had been told that some leaving from there were commercial fishermen. The men who ran or worked the big boats were gawking at us from the moment of our arrival. As we assembled and rigged our trimarans on the strip of grass next to where Ray had parked the van, one guy after another found a reason to walk past and ask if we were going to cross the bar “in those things.” I heard derision in at least several voices, while others seemed skeptical but curious. All of them shook their heads. Ray and Kenny scowled silently at the derisive and were stoically polite to the doubtful, giving terse replies to questions about our boats, which had been seasoned by years of familiarity with the process of putting in trimarans amid myriad motorboats.

Donning our drysuits only increased the circus-like atmosphere we seemed to be creating. Mine was a red-gray-black combination that made me look, according to my wife, like a space traveler in party clothes. Much as I despised the strangulating throat gusset, I agreed with Ray that the security of knowing we could survive in the water for several hours, if it came to that, was worth the discomfort. Padding around in our drysuits, though, made us appear even more like alien life forms to the fishermen.

By the time we put our trimarans into the water, a couple of the fishermen were grumbling about the time we were taking and let us know they wanted us to clear the way. We climbed into the Hobies out of knee-deep water, paddled a few feet away from the launch ramp, then began pedaling. The rest of the fishermen were clustered along the dock next to the ramp, watching us with expressions at once incredulous and comical. “Oh, my God,” I heard one of the men say. “Pedals?”

I was only vaguely aware of all the people standing and staring at us, but then I heard some of them begin to applaud.

Guffaws followed as we moved past, then a voice called out from behind us, “No guts, no glory!” followed by even louder laughter. I glanced over at Kenny in the solo Hobie, and he looked anything but amused.

As we entered the channel I heard one last voice shouting “Good luck” and wondered which one of the fishermen that was. The rain had stopped about ten minutes earlier, and the sky already began to show signs of clearing. This produced a phenomenon I’ve seen only on the Pacific coast between Northern California and southern Washington and have always found immensely pleasurable.

It’s a filmy, silvery light that lays like a substance on one’s surroundings, magically weighting everything that it touches and somehow compressing reality in a way that creates a simultaneous sense of expansion, making what’s near seem far and what’s far all but unbearably close. I’d had trouble falling asleep the night before, bothered by the thought that this could be my last night on earth, until I concluded it was that way all the time, and finally nodded off. Now, in the uncanny light of this day, as Ray opened our sail and we slid out of the channel into Baker Bay, making for the Columbia River, I felt no fear, only anticipation.

Seated in the rear position, I could see just Ray’s back, until he swiveled to look at me over his right shoulder. “You and me, brother,” he called. “Let’s live through this.”

We’ve both lived through a lot already, Ray, I thought to myself. It’s what we’re good at.

*

A pair of passersby marked the latter stage of our approach to the Columbia Bar.

Just before the first of these appeared, I had begun to wonder at what point Ray and I (and Kenny, wherever he might be; behind us was all I knew) would be officially within the Jaws. We had been moving along next to the North Jetty for at least half an hour, and the inside of the South Jetty, where it protruded from Point Adams, was increasingly visible. So we were between the two jetties, but still sailing in relatively smooth waters. The inside of the entrance to the Columbia Bar, I knew, the point where the jetties were most widely spaced apart, was almost exactly a distance of two miles across. The outside of the entrance, where ships came into the river off the ocean, and where the collision of tide and current was truly felt, was only a little more than half a mile wide.

We were at a point where the distance between the jetties was maybe a little more than a mile, I was guessing, not quite “in” the Jaws, I had just decided, when Ray pointed sharply off to his right in the direction of the North Jetty. For a moment I saw nothing, then spotted the fin moving through the water about sixty or seventy feet off our starboard side. It took another second before I recognized the large silver-gray shape moving under the water, beneath the fin, and realized I was looking at a great white shark.

It was the first one of these I had ever seen live. I knew great whites were all along the West Coast of the United States.

Ray told me later it was the first great white he had ever seen also, and that made the sighting seem especially significant, though precisely how, I wasn’t prepared to say. The main thing I was thinking at the time was that, if our trimaran capsized, we’d have more to worry about than simply managing to stay afloat until a rescue boat came for us.

Earlier, I had worried briefly that some water beast could tip the trimaran over. My concern then had been mainly about what was likely the great white’s main prey in these waters, sea lions. We’d seen several of them surface for air already, one not ten feet from our boat. Ray called over his shoulder that I should smack it in the face with a paddle if it swam any closer.

It wasn’t long after we spotted the shark that I saw the big freighter headed toward us, incoming off the ocean across the bar. I blame Ray for the way my breath caught in my throat. Before and during our first two training sessions in the trimaran, Ray had backed up his warnings that I couldn’t “cramp up or crap out” on the bar, and not be able to pedal full speed, by employing the image of some large freighter coming full speed straight at us as it entered the river’s mouth, and he and I needing to be able to pedal out of the way to avoid being crushed.

If the boat flipped, he would go over backward, headfirst into the sand, with the boat right on top of him. A broken neck seemed all but certain.

For a minute or two, when the freighter, coming from the north, began to swing in to port off the ocean, the ship looked as if it were headed our way for sure. The freighter’s left turn wasn’t nearly as sharp as it had seemed for that first minute, however, and when it actually came through the Jaws into the center of the South Channel, the ship was nearly a thousand feet from us.

*

Beyond the rampart of rocks and the view of Cape Disappointment, it was all sandy beach stretching miles up the Long Beach Peninsula to Willapa Bay. Washington’s ocean beaches are in general nowhere near as beautiful as Oregon’s, not only lacking the drama of the oceanfront down south, but with shorelines that tend toward gravelly gray rather than sandy light brown. The Long Beach Peninsula’s beaches are the best Washington has, and we were enjoying our cruise north with their relative safety in sight off the starboard side. We had stopped pedaling and were using only sail.

The swells were growing steadily larger, though, and all three of us were eying them with mounting concern. This is the first I recall of Kenny’s saying that he’d seen the wave train arriving hours earlier than expected. “I could feel it coming out of the south just as we went past Clatsop Spit,” he told me when I asked him about it later. “I was sort of trying to pretend it wasn’t happening, but I knew it was. That’s why it got so bumpy right as we crossed the bar.”

Ray was goading him a little, especially when some six-footers rolled up on us: “This is what you call a flat ocean, eh, Kenny?”

Wave predictions were usually quite reliable, Kenny insisted, in his own defense. “It was forecast to drop to as low as a half meter, then come back up tomorrow,” he said.

“Well, it’s come back up today,” Ray replied, with a derisive snicker. It was a friendly game of mockery and one-upmanship that he and Kenny played constantly.

I still wasn’t worried. The beach was right there. I could have slipped off the trimaran and swum to the sand pretty easily, I reckoned. Kenny, though, told me later that he had been worried, and was getting more worried with every passing minute. “I was watching up the coast, and I saw the waves were coming in sets of seven to nine,” he said. “There was usually only one big wave in each set, though, so I figured we were probably okay.” Bear in mind, Kenny said, “when you’re out on the ocean looking at waves, they’re harder to judge. Surfers like to study the waves for half an hour on shore before they go out, because it’s way more difficult when you’re on the ocean.”

In fact, the surfers already were out in force on the beach at Seaview, drawn by word that some very rideable waves were coming. As we approached, we saw them pointing at us, several shaking their heads. I assumed it was because we were in their way. The families and couples on the beach were watching us too, using their palms like visors against the afternoon sun that was now over our right shoulders.

Our appearance must have been dramatic, coming in off the sea in such unusual craft. We stopped and sat just outside where the waves were breaking, considering the situation. A beach landing clearly was going to be more exciting than we’d planned.

Time did slow in what I imagined might be our last seconds of life.

I can’t remember whether it was Ray or Kenny who first brought up the possibility that we could turn around, sail back the other way up the coast, recross the bar, and land at the very same dock where we’d launched a few hours earlier. They threw it back and forth for a few minutes, Kenny clearly a little more inclined to turn around than Ray was, although “I really did want to get off the ocean,” Kenny told me later. “And the beach was right there.”

I must admit that I weighed in on the side of just going ahead with the beach landing. I knew how silly it would sound to point out that I’d already gone to the trouble of dropping my car at Seaview, so I gave my other bad reason, this being that the beach landing was what we’d planned and we’d all feel regret later if we didn’t follow through.

In the end it was Ray’s call. “Let’s do this,” he said.

Kenny told us to go ahead, he’d see what happened. The big man did offer a piece of prudent advice, though, which was to try to pick the smallest wave we could, ride it in as far as possible, then try to catch another small wave to the beach.

As Ray handed me the paddle I was supposed to steady us with, he grinned at me and said, “Seems like a big wave will carry us a lot closer to shore, doesn’t it?”

I may have grinned back. A flaw we shared was the tendency to weigh all options carefully, then decide that “On the other hand, fuck it” worked too. It’s what happens to boys for whom taking action has been the only real alternative to despair.

A six-foot-plus wave came early in the next set, and Ray and I pedaled atop it. Any notion that we could surf a breaker that size in a vessel as ungainly as the trimaran vanished almost instantly. We were swung like a tilt-a-whirl car on the crest of the wave, then plunged down sideways when it began to break. My back paddling did little or nothing to correct us, and I was looking down at Ray as we inverted to well past forty-five degrees.

What we didn’t know, and Kenny didn’t either, was that the beach at Seaview was a maze of small sandbars, creating amazingly random depths. Whether the shoal we slammed into with the back of the portside ama saved us is questionable, but this collision did happen right at what felt like the tipping point, and just at the instant I thought we were going over we bounced backward briefly, then the wave whirled us again. I was on the low side for a fraction of a second, until the wave spun us even more violently, putting Ray on the bottom again.

Time did slow in what I imagined might be our last seconds of life. I was looking straight down at Ray, observing the expression of helpless terror on his face as the trimaran was flung toward vertical again. This time it really felt like we were going over, and from my position on top of the wave it occurred to me that I probably had at least a chance to leap clear, assuming I possessed even a vestige of the agility that had been the main basis of any athletic talent I’d had when I was younger. If the flipping boat caught me before I was clear, though . . . Well, that would be bad.

But Ray’s position was truly desperate: if the boat flipped, he would go over backward, headfirst into the sand, with the boat right on top of him. A broken neck seemed all but certain.

Again the back of the portside ama struck a sandbar, but this time it dug in as if to vault us further toward the tipping point. We were turning over for sure, I knew, when it finally occurred to me to pull my feet out of the pedal straps and plant them on what had previously been the bottom of the boat. I felt the trimaran shudder as it lifted me to a point where I was directly above Ray, and then, astoundingly, the aka that braced the portside ama snapped, and the sudden give that produced created some sort of counter to our forward momentum and the main hull of the boat came back down just a little as the wave spilled us out into a cavity between two sandbars, maybe thirty feet from the waterline.

I remember seeing the ama floating loose in the water for a second, and then, I’m not sure how, I was out of the broken trimaran and pulling it up onto the beach with the rope at the bow of the boat. Ray climbed out of the boat a few seconds later and helped me drag it all the way up onto the dry sand. I was only vaguely aware of all the people standing and staring at us, but then I heard some of them begin to applaud. Ray grabbed me by both shoulders, his face inches from mine, pale eyes wide, taking short, rapid breaths. “Do you . . .” he got out, then choked up. “Do you know . . .” he managed on his second attempt, but this time hyperventilation stopped his voice. He squeezed my shoulders, looked down at the sand for an instant, then again stared directly into my eyes: “. . . how close we just came to dying.” His voice was somewhere between a gasp and a croak.

“I do know, Ray. I do,” I told him. I patted his arm. “Breathe slow, brother.”

A brief expression of suspicion passed over his face. “Why are you smiling?” he asked.

“Am I?” As a matter of fact, I was. “I’m just happy that we made it,” I told him.

Ray nodded, but without conviction, as if he doubted it was that simple.

I held his gaze another moment, then turned finally to face all the people on the beach who were still gaping at us. The spectacle we’d created only really registered with me then. Stunned expressions were everywhere. Some of the surfers tried to scorn us, I think, but even they were so overwhelmed by what they’d just witnessed that they looked more dazed than disdainful. A lot of the other people were smiling, some appreciatively, like that was the best entertainment they’d enjoyed in a long time.

I was still too happy to be alive to feel embarrassed, so I smiled back. My phone burred. I pulled it out of the waterproof lanyard case I carried it in and saw that Kenny had sent me a text from out there on the sea. “Shoot a video of me coming in,” it read. I tried, but after about seven or eight minutes of keeping my phone aimed at Kenny as he paddled in place, letting waves pass under him, I got tired of it and ended the video. He later sent a long and detailed text to his brother (a waterman extraordinaire himself) explaining what was going on. Out of respect for his accomplishment, of which Kenny was justifiably proud, here’s the whole thing:

After watching their ama rise overhead twice, I hung outside

for 10 minutes timing waves, practicing backstrokes, and getting

jacked. The beat was classic 7 or 9 waves on about 8

seconds. 3 to 5 bigs and about 30 seconds of flats in between.

I chased after a fourth, backed off a steep 5 by jamming paddle

straight down on port and leveraging it off the aka to stop a

hard right broach and somehow came out of the white water

pointed straight at the beach. Max pedal on the Mirage drive

and kayak paddle to get through the impact zone. Not fast

enough and wave 6 spun me hard, so jam full vertical paddle

against starboard aka and feather to stop the oversteer.

Bounced an ama on the high tide bar and spun sideways in a

foot of water. Got out of the boat before the next wave and

pushed it ahead through 3 feet to dry sand.

I did get the last minute or so on video, and kept the camera on Kenny as he stepped up onto the beach looking thoroughly exhilarated. “Wow,” he said. “That was absolutely the scariest thing I’ve done in years.”

_____________________________

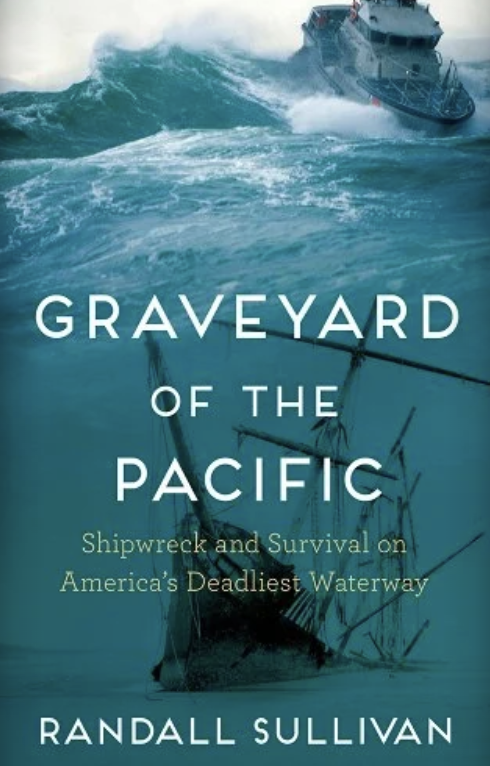

From Graveyard of the Pacific, by Randall Sullivan. Courtesy Grove Atlantic, copyright Randall Sullivan, 2023.