The first time I tell Rachelle that I love her, she answers “Five reasons.”

“What?”

“Five reasons. Give me five reasons why.”

“Five?” I say.

“Five.”

I look to the ceiling, mouth open, still as a corpse, and remain this way for a minute, maybe more. At some point, I let out a low, unpromising “um.” I’m not waiting for inspiration. I’m eliminating options—trying to get down to 20, then 10, then five, the five best.

I’ve always struggled with revision that reduces. I’m a natural maximalist, partial to parentheticals, always tilting into tangents. More is more is more. I don’t care about a blackbird that I can look at only once.

For the speaker this can feel like flying, defying the gravity of the period. But for the listener it feels like fishing with hand grenades: a long, uncomfortable process that renders whatever it yields not worth keeping. You have to pay for your tangents, either in the currency of trust or patience. I can’t, for example, tell you about my great uncle Pat, who fished with hand grenades in German lakes during the Second World War, who died last spring, leaving me this and other images. I haven’t earned it. In my experience—in love and writing—you can earn patience with your voice, the way you say something, but you only earn trust by keeping your promises.

“Five … reasons …” I repeat.

My voice isn’t earning much.

In this moment, I wish I could say everything. But to say everything would be to stress nothing, to give the profound and the trivial equal weight. It would be boring. “I love you” is an inherited sequence. In this moment, she’s asking only to be known. For that I need the right words in the right order.

I don’t remember what I said all those years ago, and I don’t mind that now. I’ve never had much interest in the finished utterance, the one you can’t take back. The mind tends to return to the nebula of things left to be said. Whatever the words and whatever the order, it’s good enough to buy me a measure of trust (or perhaps a measure of patience).

Time continues at its plastic pace. Experience, like language, accumulates. And love, like writing, tends to want another word.

The second time I tell Rachelle that I love her, she says “Five more… New ones.”

*

My weakness is excess—not merely a matter of style, but a loose muchness, and worse, a militant revanchism that insists on retreading ground covered in old essays, stories, and poems.

In an earlier draft of this essay—which began somewhere else, far from the version you’re reading—Rachelle, a poet and my forever first reader, leaves several comments urging me to return to the path, suggesting that I haven’t earned whatever it would take to lead her off it toward uncertain reward. She finishes reading the piece at two or three in the morning, while I sleep, and I read her comments a few hours later, while she sleeps.

The sun has barely limned the treeline, but already the little nectarine rondure at the bottom of the laptop tells me the air in our office is 83 degrees. Our cats take turns licking my ankles and walking across the keyboard. As I tap open comment after comment, heat rises in my chest, curls around the backs of my ears.

this is a bit out of place—maybe we need more context. but also, if you look at this section paragraph by paragraph, there is a bit too much skipping going on.

Deeper into the draft the comments become shorter and Rachelle takes an iron to her question marks.

Not earned!

Elsewhere she points out that I’m revisiting material I just covered in another, published essay. I vow to slow down, to print a draft, drawer it for a week, two weeks, a month. But I’ve made this promise before. Her comment about revisiting material reminds me of another note she left on a draft of a different essay, one that I’d been laboring on for two years, beginning shortly after the start of the pandemic.

i think there’s a much shorter version of this essay in here. you get away from yourself a lot, and it’s hard to hold what’s amounting to your whole life’s story within this space.

I know what I need to do. I click, tug the stiff gray shroud across a line, a paragraph, a page, then another. Ctrl-X.

In a separate document titled “Miscellaneous,” which I never close, I begin a new page, a motion like opening an empty drawer at a moratorium. I put a heading at the top, one that will bud a new jumplink in a table of contents that now spans two pages. Ctrl-V.

The room is no cooler, but I feel relief like a breeze. I’m free to try again. “Kill your darlings,” something William Faulkner supposedly said, is one of those memorable maxims that teachers of writing love to tell their young students. I’ve learned to revise around this rule. I prefer to keep my darlings on ice.

*

Hogwarts looms over the blue carpet from the cliff of the window seat. Below it, the Basilisk’s plastic eyes watch unblinking from behind the bars of a Gotham jail, sharing a cell with Batman and a bank robber in a classic black beanie and stripes. The coffee table is an aircraft carrier, with Slave I, an X-Wing, and a terrestrial helicopter on the runway, ready to soar. Beside it, the ribbed cushions of the couch are upended into a kind of vast, upholstered Utah, a canyonscape where ninjas in a dune buggy hunt Indiana Jones. And across from this a Viking ship, with press-ganged soccer players at the oars, sails the linoleum, headed straight for the dragon nesting in dad’s Tevas.

Twenty years before the megamergers of Warner and Discovery and HBO, Disney and Marvel and Fox, Amazon and MGM, my own Cinematic Universe is breaking physics, logic, and intellectual property rights to accommodate madcap crossovers, mostly in the form of Lego sets that, in the space of an afternoon, might sprawl across the whole first floor of the house. I cover the carpets, occupy the kitchen counters, fills the caves between the legs of the dining room table. If I could have reached the ceiling fan I would have used the blades to port flying pirate ships.

The universe expands until 4:30pm. Outside an engine crests, ceases. A car door closes. Then the unmistakable sound—draft-stopper squeaking on the foyer’s tile floor. I keep playing as mom sets down her work bag in the hall, begins sorting the mail on the kitchen table.

“Aidan,” she says, opening the fridge, glancing at a recipe neatly ripped from a magazine. “Start cleaning up.”

“Mom,” I say, summoning all the emphasis my eight-year-old voice can carry, “I’m in the mid-dle of the stor-ry!”

Sometimes I can bargain for more time, insisting with real urgency that I must keep playing after dinner, that to put the Legos back in their bins now only to bring them out again in an hour would be a stupendous waste. Now, as a childless adult, I can’t imagine returning from work each day to find that a whinging imp has covered every surface of my home in arrangements of plastic that cannot be disturbed. Mom didn’t always indulge me, but I think she understood what motivated me. It wasn’t laziness, a refusal to pick up. I was telling a story with the toys, a story that I wanted to live inside, physically. And I was only interested in the story of everything. If I focused for a while on the Viking ship or Indiana Jones, I hadn’t forgotten about Boba Fett or the Basilisk in jail. I had to keep everything out, in suspension, so that everything remained possible.

*

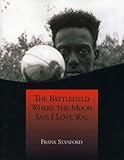

I remember the Legos when I read my friend Ata Moharreri’s interview with James McWilliams, the writer undertaking the first biography of the poet Frank Stanford. They read a little-known poem called “Tapsticks” and Ata notes that it feels like an “outtake” from The Battlefield Where the Moon Says I Love You, Stanford’s 15,283-line epic. McWilliams agrees.

I remember the Legos when I read my friend Ata Moharreri’s interview with James McWilliams, the writer undertaking the first biography of the poet Frank Stanford. They read a little-known poem called “Tapsticks” and Ata notes that it feels like an “outtake” from The Battlefield Where the Moon Says I Love You, Stanford’s 15,283-line epic. McWilliams agrees.

I look at it sort of like this—very serious bread bakers have a big vat of starter that they feed with fresh flour and yeast. When bakers want to bake bread, they take a small scoop of that starter to bake their bread in an oven.

I think that is what Frank is doing. I think he’s sort of maintaining The Battlefield like it is a huge vat of constantly fermenting starter that he dips into from time to time to put out his lyric poetry.

I think about a folder in the cloud, the one called “Writing.” And the folders within it, branching universes: “Poems” and “Essays,” and within that “Outtakes,” and within that the file called “Miscellaneous,” now over a hundred pages. And I think of the stories that as a child I told and retold in bright plastic—before I found a world of words that I never had to pack away.

Most Stanford readers understand Battlefield to be an excerpt of a longer work that Stanford began as a teenager, St. Francis and the Wolf. Yale’s Beinecke Library has preserved 60 pages of that adolescent manuscript, clearly a fraction. McWilliams wonders if the total page count may have exceeded 1,000. He notes that he ran his theory by another, unnamed poet who confirmed it and further suggested that other poets have used the same technique. On a hunch I text the poet Forrest Gander, one of the keepers and complicators of Stanford’s legacy, who borrowed elements of the late poet’s life for his novel As a Friend. “I’m hoping the mystery poet is you,” I say, pasting the excerpt.

Most Stanford readers understand Battlefield to be an excerpt of a longer work that Stanford began as a teenager, St. Francis and the Wolf. Yale’s Beinecke Library has preserved 60 pages of that adolescent manuscript, clearly a fraction. McWilliams wonders if the total page count may have exceeded 1,000. He notes that he ran his theory by another, unnamed poet who confirmed it and further suggested that other poets have used the same technique. On a hunch I text the poet Forrest Gander, one of the keepers and complicators of Stanford’s legacy, who borrowed elements of the late poet’s life for his novel As a Friend. “I’m hoping the mystery poet is you,” I say, pasting the excerpt.

“It was said of Dylan Thomas that his early notebooks contained all the raw material for the books of poems that he wrote later,” Forrest tells me, noting Alan Dugan may have done something similar.

With this shove, I can think of a few other writers who seem to have tried versions of this technique. Yoknapatawpha County, the apocryphal setting of almost all of William Faulkner’s fiction, may have existed in the writer’s mind as something akin to St. Francis and the Wolf, an unstable, semi-narrative cauldron of tone, image, characters, history, and geographic touchpoints. From another angle, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “Gatsby Cluster,” five or more short stories that he wrote as warmups for his masterpiece, also appear to be incarnations pulled down from a larger common substance.

I remember a line from an essay by Elisa Gabbert, which appears in her 2018 book The Word Pretty; she keeps “lyric notebooks,” she says, storehouses of narration and reaction that she harvests for poetry, full of “good lines [that] just arrive, as if from another mind.” Each line is a thread that passes through the page from some otherwise unreachable origin, and the writer can take any number of these and spin them into poems, essays, stories. Rachelle keeps lyric notebooks, too. But these seem less like burping vats of starter than herbariums of intellect and music.

I remember a line from an essay by Elisa Gabbert, which appears in her 2018 book The Word Pretty; she keeps “lyric notebooks,” she says, storehouses of narration and reaction that she harvests for poetry, full of “good lines [that] just arrive, as if from another mind.” Each line is a thread that passes through the page from some otherwise unreachable origin, and the writer can take any number of these and spin them into poems, essays, stories. Rachelle keeps lyric notebooks, too. But these seem less like burping vats of starter than herbariums of intellect and music.

Perhaps closer is Heather Christle, who describes her 2019 lyric memoir and cultural study The Crying Book as a five-year project “to make a map of every place I’d ever cried” and then “a map of every place that everyone had ever cried.” In interviews, Christle relates the book’s beginnings, first as what might have been a prose poem, and then an essay, before she realized—“oh shit”—that she was writing a book. In Lit Hub, Christle recounts the “dread” she felt when it came time to shape that book from turn “the great mass of prose” she had compiled over five years.

Perhaps closer is Heather Christle, who describes her 2019 lyric memoir and cultural study The Crying Book as a five-year project “to make a map of every place I’d ever cried” and then “a map of every place that everyone had ever cried.” In interviews, Christle relates the book’s beginnings, first as what might have been a prose poem, and then an essay, before she realized—“oh shit”—that she was writing a book. In Lit Hub, Christle recounts the “dread” she felt when it came time to shape that book from turn “the great mass of prose” she had compiled over five years.

I have never attempted to turn “a great mass” of poetry or prose into anything like The Crying Book, or to transmute something like St. Francis and the Wolf into a Battlefield. But I believe in the process of thematic accretion behind both these epic projects. In early attempts at both fiction and poetry I was content to save infinite, timestamped drafts, but I never suspected I would need to consult them. The more time I spent with a set of characters, the quicker I could feel my way through a scene, only ever sharpening my sense of what they were up to. Paradoxically, the infinite possibilities of fiction were easier to navigate than the tangled guts of the real. Every time I tried to write about myself, working toward a style of lyric memoir, I felt an undertow toward the unmapped totality of my experience. It became much harder to cut material—I wanted, once again, to keep everything available, everything possible. Only by accident, working on a hybrid, book-length project, did I begin to save chunks of life, unfit for the present purpose, in a new unruly, fungal document that has expanded steadily. Unlike early drafts of finished poems or fiction—all forgotten—I have returned to this swarming resource many times. I may continue to return as long as I live and write.

Shortly after reading the McWilliams interview, I write to Heather Christle to ask about her work in progress, a nonfiction book about London’s Kew Gardens. I noticed, I say, that Kew Gardens appears as a new leitmotif in the late pages of The Crying Book. “I did cut a whole lot from The Crying Book, but none of it ended up in the new project, I’m afraid,” she tells me. “It did in some ways originate from The Crying Book in that my publishers asked me to write some essays to drum up publicity when that book was coming out, and one of those essays (which I never published) led me to realize what the next book would be.”

I’ve yet to find evidence of any writer besides Stanford who “maintained” a larger, unpublished but complete-in-itself epic work of some kind—either on the page or in the mind—like The Battlefield Where the Moon Says I Love You or St. Francis and the Wolf. But it seems a common phenomenon for many writers that chunks removed in the editing process, preserved in neurons, bytes, or scrap paper, are often the yeast that starts the next work.

*

Besides my “Miscellaneous” file, there is one other collection of fragments critical to my writing. This one exists only in my mind, but it feels as real as any hardback. It comprises the absolutions of other writers—admissions that to write anything is to accept at the beginning some measure of failure in the pursuit of perfect communion.

Lines from T.S. Eliot’s “East Coker,” second of the Four Quartets, come most often to mind:

Trying to use words, and every attempt

Is a wholly new start, and a different kind of failure …

Because one has only learnt to get the better of words

For the thing one no longer has to say, or the way in which

One is no longer disposed to say it. And so each venture

Is a new beginning, a raid on the inarticulate

With shabby equipment always deteriorating

In the general mess of imprecision of feeling,

Undisciplined squads of emotion.

The irony: I have never read a better description of writing. This, this, is the failure Eliot felt fit to share.

Or there is a passage in Feodor Dostoevsky’s The Idiot that has haunted and comforted me since I first encountered it, reading the book on the porch swing at home in one of the long, still, interchangeable weeks of a teenage summer:

Or there is a passage in Feodor Dostoevsky’s The Idiot that has haunted and comforted me since I first encountered it, reading the book on the porch swing at home in one of the long, still, interchangeable weeks of a teenage summer:

There is something at the bottom of every new human thought, every thought of genius, or even every earnest thought that springs up in any brain, which can never be communicated to others, even if one were to write volumes about it and were explaining one’s idea for thirty-five years; there’s something left which cannot be induced to emerge from your brain, and remains with you forever; and with it you will die, without communicating to anyone perhaps the most important of your ideas.

Somewhere in the intervening years my mind would link these lines from The Idiot with those above from Eliot’s Four Quartets. To me, they give permission to fail without at all lowering the stakes. And they give permission to fail again.

Somewhere in the intervening years my mind would link these lines from The Idiot with those above from Eliot’s Four Quartets. To me, they give permission to fail without at all lowering the stakes. And they give permission to fail again.

I think of this “something at the bottom” listening to Hanif Abdurraqib read new work to an audience in Buffalo in April 2022. “The jenga block of all my writing,” he says, “is a visceral faith that I might see someone I loved again in the afterlife.” I write it down in a pocket notebook. (I keep these, too.) It’s a perfect utterance—the jenga block of all my writing. But I suspect that, like Dostoevsky, Abdurraqib will spend another 35 years or longer, the rest of his life, explaining this idea, trying again and again, and feeling at the end there remains something left over, something he wasn’t able to make us understand.

I don’t know the jenga block at the bottom of my writing. But I believe that I begin from the hope that in writing and revising I will learn to say something that I will never have to say again. I have scant evidence to support this hope, and much more evidence to support the opposite view, Dostoevsky’s. I keep returning to some of the same themes, the same scenes. When Rachelle reads a draft of a new essay and notes that I’m revisiting something, or spiraling out into my “whole life story,” she’s right. So I cut it, the excess, the loose muchness, and preserve it—whether the whole botched attempt in a timestamped draft or merely the excerpt in my “Miscellaneous” file. I’m at peace with repeated failure.

“I feel the most seen getting constructive feedback,” Rachelle tells me, perhaps a consolation for the lack of praise she leaves in my margins.

She’s right. This is another kind of communion, the intimate dialogues that happen in felt pen and digital sticky notes. Cut this. More. Do you mean ___? At its best, the editing relationship transcends language, that incommensurate medium, and speaks from an understanding beyond. Unlike lower-stakes exercises—knowing glances, nods, I know what you means—editing another’s work acknowledges inevitable failure, is premised in the inadequacy of language. But it is also an urge against destiny: a call to pick up the tools again, to fail closer to that “something at the bottom.”

When I preserve my botched attempts, Rachelle’s comments come with them. Into the yeast, that mass of dead letters that ferments, breathes with new life, new language.

In the hot stillness of the apartment, in my hour or two alone, I appreciate that all air waits for language to move it. Soon we’ll meet over lunch or dinner, or take a walk to the mailbox or the raspberry patch around the corner. We’ll start to tell each other everything: how we ventured all; how nothing, really, is ever lost.

“I love you—I love this life,” I’ll say—ready for the rejoinder and the challenge, smiling toward a new, worthy miss—beginning again from a place of hope, the eternal starter, that great bacterial store of things still left to say.

The post Stet: On Cutting—but Keeping—Everything appeared first on The Millions.