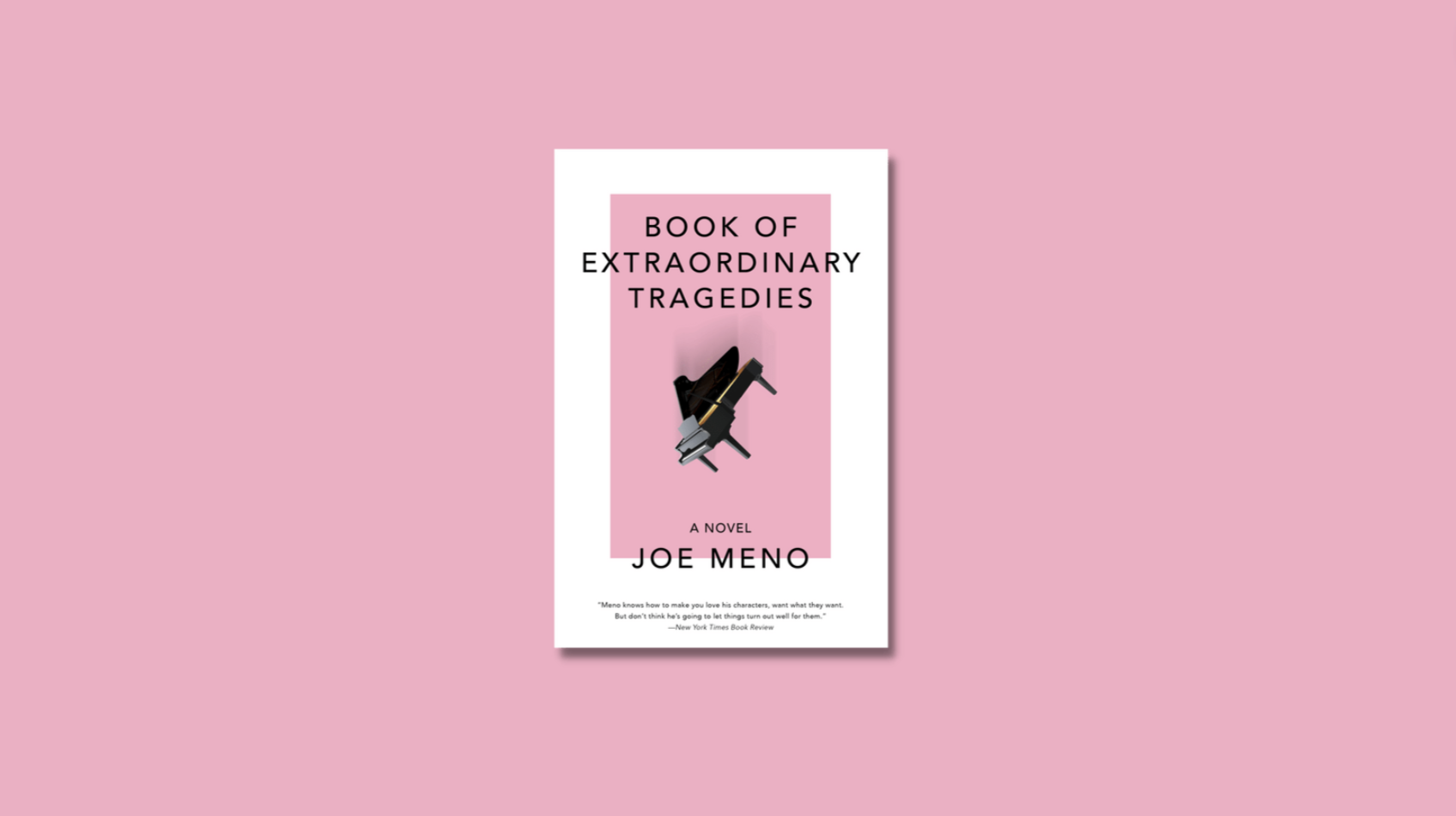

Joe Meno’s new novel, Book of Extraordinary Tragedies, is told through the eyes of twentysomething musician Aleks, who is the product of a gifted, exceedingly odd family and—in an especially cruel twist of fate—has lost much of his hearing. Set against the backdrop of the 2008 economic meltdown, Book of Extraordinary Tragedies is an incisive exploration of ethnic identity, uneasy family legacies, thwarted ambitions, and the city of Chicago itself.

Richard Klin: Let’s start at the beginning, with how this book came to be.

Joe Meno: The book originally started with this story about these two brothers I’d written almost 15, 16 years ago—the narrator and his little brother Daniel. And it was a short story that I’d actually submitted for the Nelson Algren Award that the Chicago Tribune gives out. I won the award, and it was this major turning point in my career.

So I had these two brothers and I kept coming back to them every couple months, in between projects. It was set on the southside of Chicago, in the neighborhood where I grew up. I just couldn’t figure out the shape or the structure to make it feel like a novel. I had these scenes and these kind of sections. When the older sister, Isobel, finally showed up, she brought a lot of interesting challenges and drama; that relationship between Aleks and Isobel is the center of the book.

Over the last 18 years or so I’ve also been living with hearing loss and bringing that experience into the world of the book— making that part of Aleks’s story in that he loves music. He lives in this world of music, he’s constantly thinking about music, but he can’t really participate in the way that he used to, or the way he wishes he could.

RK: Looking at Aleks and his brilliant, messed-up family, I was reminded of J.D. Salinger’s Glass family—although Aleks’ family doesn’t have the Glasses’ money. So, really, they’re like the low-rent Glass family. Do you see any similarities between the two clans?

JM: I remember vividly, when I was maybe 18 or 19, down at the University of Illinois, sitting in the dorm room of this girl that I was dating, reading Franny and Zooey. I was supposed to go to class but didn’t, so she went off to class and left me in her dorm while I was reading.

RK: There’s a scene in the book where Aleks stays in his girlfriend’s dorm, reading, while she goes off to class.

JM: And I read the whole book. I don’t know if I’d ever done that—just read it straight through. I think it’s less than 200 pages, but I read it straight through. She came back and I had just finished. It was one of my most profound reading experiences. I think maybe because of my age, that story just lodged itself in my imagination. The story of Aleks, Isobel, and Daniel—in terms of the challenges they face—is a pretty different story. But there’s something about the tone and the fact that those Salinger characters care so deeply for each other, even though they’re flawed, felt really powerful. In the end it ends up echoing some of the things I originally loved in that Salinger book about these people who are really talented, but are kind of their own worst enemies. There are obstacles as they’re transitioning from childhood into adulthood.

RK: They’re very devoted to each other. It’s a paradox. I think of the quote—which I’m probably mangling—that home is the place where they have to take you in.

JM: Exactly! Speaking from my own experience, I have an older sister, a younger sister, and a younger brother, and they’re incredibly interesting, amazing people. And nobody can frustrate me more than those people. And nobody can also make me feel so complete. It’s this very, very strange paradox. No matter how old you are, how far you are in your life, those people know you better than anybody else. And they know your vulnerabilities, they know what you’re weak at. They can support you in a way that few other people can.

RK: Music has always inflected your writing, but Book of Extraordinary Tragedies takes it many steps further. The book is divided into movements. There are speculative musical compositions too, which I find fascinating—Aleks is constantly composing little classical pieces in his head. There’s also family history via music. And then there’s silence, not just with Aleks, but with his niece Jazzy, who’s also hearing impaired.

JM: I’ve always used music as a device to understand tone and thinking about the mood of a book and the feeling of a book. The one that comes to mind is How the Hula Girl Sings—I wanted it to feel like a Johnny Cash record. Hairstyles of the Damned should feel like a punk record. A lot of it has to do with mimicking tone and language. Even something like the length of a chapter. Hairstyles of the Damned had very short chapters and that was kind of emulating the way those great, less-than-two-minute punk songs operate.

JM: I’ve always used music as a device to understand tone and thinking about the mood of a book and the feeling of a book. The one that comes to mind is How the Hula Girl Sings—I wanted it to feel like a Johnny Cash record. Hairstyles of the Damned should feel like a punk record. A lot of it has to do with mimicking tone and language. Even something like the length of a chapter. Hairstyles of the Damned had very short chapters and that was kind of emulating the way those great, less-than-two-minute punk songs operate.

Once I really thought about the connection between these characters and their love of music, I figured out that Aleks’s understanding of music is as a survival tool. When things happen in his life, the way he deals with them is imagining them as pieces of music. He goes to the convenience store and these guys make fun of him and he starts imagining it as a piece of music. At least in my own life, music has this mechanism for helping us survive things that sometimes you feel you otherwise couldn’t face.

It was only at the third or fourth draft, pulling in these different sections and chapters together that I realized the shape of this book could actually just be a piece of music. I could actually structure this book like a four-part symphony. So I started figuring out how these different sections would work, each one with their own feeling and tone.

And then there’s what you said about silence. Since I started losing my hearing, I recognize there are records I love and I just don’t hear them the same way anymore. And as I really started to accept my loss, I know I could put on The Beatles’ White Album and there are things I just don’t quite hear—especially if it’s more complicated, if there are things going on in the background; if there are counter-melodies. I lose it to the point where sometimes a major melody will sound dissonant or even almost like a minor. And I lose the melody. And that’s frustrating because I know how these songs are supposed to sound! And so, over the last couple of years, what I’ve been trying to do is a couple times a day is just observe the way silence works. I’m hearing ambient sounds differently than I did 20 years ago. I can almost map out and document silence and the way silence works: Instead of saying, I’m going to focus on what I’m missing and the things I don’t hear, shifting the emphasis to, What do you hear that’s totally different?

I have ongoing tinnitus in my ears, so it’s just a constant ringing, and it’s more pronounced at night. So at night I just hear these really fascinating, strange tones and sounds. And that’s something that I try to bring into the world of the story and specifically with Aleks. He’s struggling to accept this loss. And of course sound and silence are intertwined—to have awareness of one means to have awareness of the other. And it’s only because I don’t hear the same way I used to that I’ve been forced to appreciate this other thing.

RK: A lot of your work really mines the quotidian, which—as you’ve said—seems to be ignored in most books. Often, people don’t work; they don’t have a factory job, or crummy nine-to-fives.

JM: It makes sense when we look at the history of literature, certainly English literature: Who was able to publish these books and sit down and write these books? Who was the audience, originally, for those books? They weren’t people who were working nine-to-five or factory jobs. But I think of my grandfather, who listened to classical music, loved Moby-Dick. This guy had the imagination and capacity and interest, even though—if you were from the outside—if you’d see him when he came home from working at the steel factory, you’d assume otherwise.

JM: It makes sense when we look at the history of literature, certainly English literature: Who was able to publish these books and sit down and write these books? Who was the audience, originally, for those books? They weren’t people who were working nine-to-five or factory jobs. But I think of my grandfather, who listened to classical music, loved Moby-Dick. This guy had the imagination and capacity and interest, even though—if you were from the outside—if you’d see him when he came home from working at the steel factory, you’d assume otherwise.

There are so many incredible writers who have written about working class characters, from Stuart Dybek to Jesmyn Ward. It feels like it shouldn’t be surprising that in the year 2022 we have characters who are struggling, who are between jobs, who are forced to work. When I was in college I worked at this plastics factory. That was as great an education as any class I took that year! Not just in the challenges people were forced to endure as they’re doing this work day after day, but noticing that there were people my parents’ age who were working there. What did that mean in terms of social equality and opportunity? Unless you’re forced through circumstance to work in manual labor, it’s really easy for those people to become invisible and not be given a voice in a lot of fiction.

RK: Toward the end of the book, Aleks muses about “how impossible it is to ever contain, to see the beauty of the entire world—all you ever get is a glimpse before it quietly disappears.” It almost seems like this is an artistic credo to capture those little moments.

JM: That concept comes directly out of the culture of the family in which I grew up. One half of my family is Italian, the other side is Yugoslavian and Polish. Growing up, we’d go to visit my Polish or Yugoslavian aunts and uncles, and there’d be this kind of silent contest: They’d be sitting, quietly drinking, eating, and someone would suddenly march out this incredibly tragic story, and then someone else, a couple of minutes later, would try to one-up them. It would be one after the other. And that’s what inspired this game that Aleks and Isobel play, what Aleks calls “a game where we tried to come up with the worst thing that could happen, a game which later came to be known as Who Suffers More?”

But it was real. And at the time, I just accepted: This is what families do. They sit around for two hours and listen to these really horrifying stories. And it’s not like anyone clapped! They would listen to it and kind of nod. Only later, when I started dating my wife and she would come to a family dinner, she’d be like, “Oh my gosh—these stories!” But that’s how they express themselves. That’s how they express joy. They express this joy by looking at how terrible and sad something can be. They believe happiness is possible—it just doesn’t last. We don’t have any right to expect it to last; we just don’t have the right to expect every day to be like that.

Now, on the other side of my family—the Italian side—it was the complete opposite. Their culture was radically different. I didn’t recognize it at the time, but there was instruction in appreciating catastrophe and tragedy. It’s the one constant. I feel like that’s something in our culture right now, this understanding of tragedy and how reoccurring and frequent it is. It seems like that’s something we’re all struggling with. The idea that these terrible things happen. Growing up in my family, my feeling is that terrible things happen whether we choose to have them happen or not—and all you can really do is try and locate those small moments of joy that you otherwise sometimes would walk past and try to be in those moments as often as you can.

In that moment you read from, Aleks is on the beach and listening to this Mozart symphony. And it’s a symphony that his whole life his dad has been pushing on him to prove how brilliant Mozart is. And he hates Mozart, so he hasn’t been able to really listen to it. But it’s after all these challenges and his ability to change and grow, to step outside his neighborhood—that he can listen to this piece of music and hear that even though his relationship with his father is fraught, that he can actually, finally, hear this beauty.