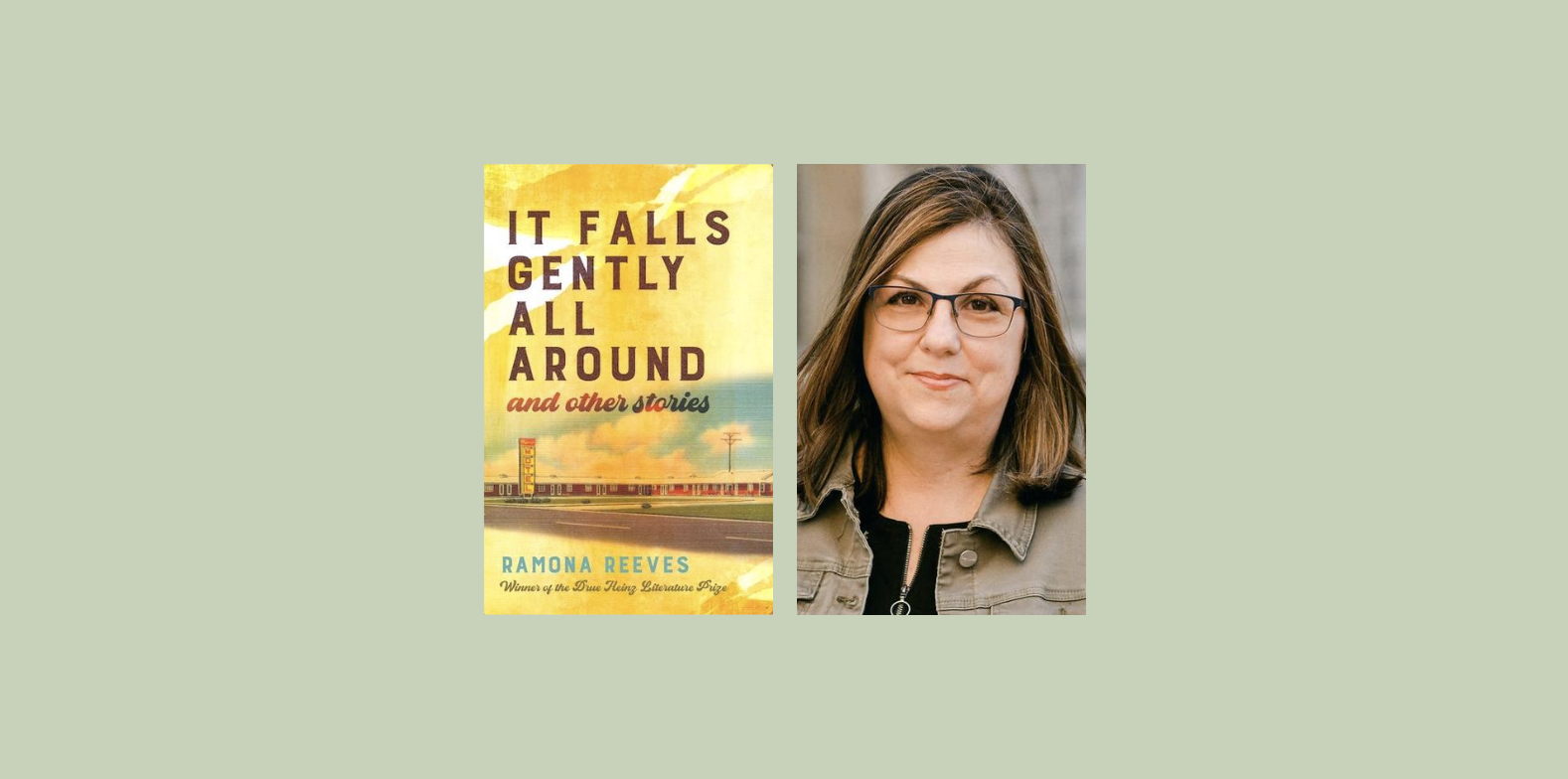

I first met Ramona Reeves in a nine-month-long fiction workshop, where I soon formed a sincere respect for the depth and verisimilitude of her work. Reeves is the debut author of It Falls Gently All Around and Other Stories, which won the 2022 Drue Heinz Literature Prize and will be published this month by the University of Pittsburgh Press. A collection of linked short stories set in her hometown of Mobile, Alabama, the book explores themes of class, sexuality, gender, race, and reinvention. Throughout, an unforgettable cast of characters faces daunting hardships—heartbreak, violence, miscarriage, alcoholism, grief—yet somehow, they press on toward the light.

Over an afternoon Zoom meeting, I spoke with Ramona about her experience as a lesbian writer from the South, perseverance, second acts, and the value of authenticity.

Shannon Perri: I want to start by asking about your relationship to Mobile, Alabama. Did you grow up there?

Ramona Reeves: I did grow up there, but as I became an adult and realized that I was gay—I also grew up Southern Baptist—suddenly I felt very cut off from the city. I started to realize that belonging there also meant fitting in, and I didn’t fit in anymore. In that way, I’ve had a difficult relationship with it. In the last five or six years, I’ve come back around to embracing Mobile, even though I know more now about its tangled and troubled history. There’s a huge opportunity there for change.

For me, writing forces me to really look at people, even people who I don’t have anything in common with or who might not like me because of my sexual orientation. It makes me more compassionate toward the ways in which they might be damaged because we all are in some way. Writing helps me see people at that human level. But of course, not everyone deserves my compassion.

SP: This collection definitely paints people at their most human level, and in doing so it explores their capacity to evolve. What attracted you to this topic of self-evolution?

RR: I thought about the characters searching for authenticity, trying to figure out a way to be authentically themselves in this world. I feel like there’s a point that a person reaches in their life—I don’t know that it’s a particular age for everyone, but it seems like it happens a lot in our forties—where there’s a moment of reflection where people think, Oh crap, I’ve lived half my life. Am I living it the way that I want? How’s it going? Am I stuck? Do I want to be somewhere else? Someone else? Just thinking about how one’s life might play out and what the meaning of it is—those are big questions. I’ve probably had that moment in my life several times.

SP: Linked short story collections are fairly unique. What drew you to the genre?

RR: I started this book in my MFA program back in 2009 as part of a class where we read linked short story collections, and we had to write the first few stories for one. I wrote the first four or five stories, and those sat for a long time before I went back and said, I want to try and do this, in part because I read Olive Kitteridge during my MFA. Then I read it again, and I still love that book for so many reasons. I wondered if I could do something similar with Mobile like Elizabeth Strout did with Maine, and with characters who are not young, maybe not Olive’s age either, but in that middle age area.

RR: I started this book in my MFA program back in 2009 as part of a class where we read linked short story collections, and we had to write the first few stories for one. I wrote the first four or five stories, and those sat for a long time before I went back and said, I want to try and do this, in part because I read Olive Kitteridge during my MFA. Then I read it again, and I still love that book for so many reasons. I wondered if I could do something similar with Mobile like Elizabeth Strout did with Maine, and with characters who are not young, maybe not Olive’s age either, but in that middle age area.

SP: I don’t know if you’ve read Corpus Christi by Bret Anthony Johnston, but I thought of his collection while reading yours. Only some of the stories are linked, but they all center on a specific place. I also thought of There There by Tommy Orange, though that’s actually considered a novel. How do you see the distinction between a novel and a linked story collection?

RR: I see my book as a linked short story collection and not a novel-told-in-stories. I originally thought it was a novel-told-in-stories, and I tried to sell it as such, until I realized it wasn’t. With There There, all of the stories move toward an explosive climax. A lot of the novel-told-in-story structures I’ve seen do that. I do feel like there is something of an arc in my book, but I don’t think it’s a propulsive, everything-comes-together narrative. That’s what’s nice about linked short stories; there is a novelesque quality to them, but they don’t always have that clean arc and climax. They meander a bit more than a novel might.

SP: One could argue that’s truer to life. Did you face any particular challenges while writing in this genre?

RR: Yes, for sure. As I said, I initially thought, I’m going to write a novel-told-in-stories, so I’ll have each story stand independently, but I’m also going to create something close to an arc. Then after trying to sell it that way and being told, “Well, you could create more of an arc,” I resisted that idea because I felt like the way that it is, is the way that it needed to be. In revision, I started to think more about the spaces between the stories, the years that go by that aren’t mentioned. I began looking at the whole landscape and how the stories were interacting with each other and thinking about characters that might be in the background in one story, in the foreground in the next. Working with all those moving parts was harder than I thought it would be. I asked myself, Which of those stories do I want to tell? Which make sense to tell? It’s cool that with this form you can do that. Usually, with a traditional short story you write it, and that’s it. You don’t see the characters again or the many stories of their lives.

SP: You’ve spoken some about the book’s drafting and publication journey. Could you walk us through the process of completing the manuscript and finding it a publisher?

RR: I started working on the book again probably three years after my MFA and just decided, Okay, I’m going to do this. I spent two years or so finishing the first draft, just getting all the stories written, tossed out one or two and wrote different ones. Then I went through and revised each. Some were in better shape than others. I mean, some stories I revised eight times—one I revised more than 30 times, and that took a few years. I finished the book, or at least the version I was ready to send out, at the end of 2018. I sent it to agents. Agents responded. Some of them responded very positively. But basically, from the feedback I was getting, I realized I had written a linked short story collection, and that it wasn’t reading like a novel. During that time, I started work on another book, a novel, and I let It Falls Gently All Around sit. That was hard because when one book doesn’t go the way you think it’s going to go, there’s a bit of licking your wounds.

Eventually I read the manuscript again and worked on it here and there. Then I sent it to the Drue Heinz Literature Prize, maybe the day before the deadline. I wasn’t sure if I was going to send it out, but there was no fee, so I thought, Okay, I may as well put it in the pile. When I won, I couldn’t believe it. You just never know. That’s what this whole experience has taught me. You never know how things are going to go or what’s going to happen, which is why it’s always good to keep writing.

SP: You recently tweeted something about how we as a writing community focus plenty on craft, language, et cetera, but not enough on knowing oneself. As we wrap up, I was wondering if you could expand on that thought.

RR: Coming out in the 1980s was certainly easier than coming out in, say, the 1950s, but it still wasn’t like, wow, everybody’s really happy about this. I think a lot of people flocked, as I did, to Chicago or New York or San Francisco, wherever you could go and feel safe. Figuring out who I was meant coming to terms with my identity as a woman who loved women.

Figuring out who I am has also meant giving myself permission to write the way I write, and to write the book I wanted to write. I went through my MFA and took various classes, and they were all great, but there was a point afterward where I remembered that the reason I wanted to write in the first place is because I fell in love with reading sentences and with language. I realized that maybe it’s not that the craft needs to be perfect and structure needs to be perfect in my stories—maybe it’s that I need to tell my stories and learn how to make use of those elements in a way that feels organic to me and my work.

SP: It goes back to authenticity.

RR: Yes, giving myself permission to express my voice plays into that. If a person doesn’t know who they are, I don’t know how they’re going to be able to convey who anybody else is on the page and have it come across as honest.