I once admitted a fondness for The Catcher in the Rye, and somebody challenged me: “Read it again.” I was kind of offended. It was true I hadn’t read it in twenty-five years, but I read it twice in high school, at fifteen or sixteen, each time in the span of a day, and I remembered the feeling it gave me. This person was so confident I wouldn’t like the book anymore, as an adult. I was confident I would—yet, I was reluctant to do it. I often reread dog-eared and underlined passages from books, and I reread whole poems, because I never seem to remember poems, even my favorite poems, when I’m not reading them. But I rarely reread whole books, nonfiction or fiction. It doesn’t suit my constitution.

I once admitted a fondness for The Catcher in the Rye, and somebody challenged me: “Read it again.” I was kind of offended. It was true I hadn’t read it in twenty-five years, but I read it twice in high school, at fifteen or sixteen, each time in the span of a day, and I remembered the feeling it gave me. This person was so confident I wouldn’t like the book anymore, as an adult. I was confident I would—yet, I was reluctant to do it. I often reread dog-eared and underlined passages from books, and I reread whole poems, because I never seem to remember poems, even my favorite poems, when I’m not reading them. But I rarely reread whole books, nonfiction or fiction. It doesn’t suit my constitution.

In his essay “First Steps Toward a History of Reading,” Robert Darnton describes a theory of “intensive” versus “extensive” reading attributed to historian Rolf Engelsing, who argued that people read “intensively” between the middle Ages and the eighteenth century: “They had only a few books—the Bible, an almanac, a devotional work or two—and they read them over and over again, usually aloud and in groups, so that a narrow range of traditional literature became deeply impressed on their consciousness,” Darnton writes. After that, supposedly, people started reading “extensively”: “They read all kinds of material, especially periodicals and newspapers, and read it only once.”

In his essay “First Steps Toward a History of Reading,” Robert Darnton describes a theory of “intensive” versus “extensive” reading attributed to historian Rolf Engelsing, who argued that people read “intensively” between the middle Ages and the eighteenth century: “They had only a few books—the Bible, an almanac, a devotional work or two—and they read them over and over again, usually aloud and in groups, so that a narrow range of traditional literature became deeply impressed on their consciousness,” Darnton writes. After that, supposedly, people started reading “extensively”: “They read all kinds of material, especially periodicals and newspapers, and read it only once.”

Engelsing, Darnton writes, “does not produce much evidence for this hypothesis.” But the model maps nicely to my own reading life. As a child I read intensively, the same few books over and over. They weren’t world-historical or holy texts, but standard-issue YA, Louis Sachar and Judy Blume; books I came upon randomly, at bookfairs and in the strip-mall second-hand bookstore my mother took me to, or in the back of Waldenbooks or B. Dalton. A few were hand-me-downs from my mother’s own childhood (like The Boxcar Children). It was partly an issue of access—I couldn’t drive to the library myself or just buy more books whenever I wanted. I also found it comforting. Those books, like a song on a jukebox, produced a reliable feeling. Abruptly, in college, I stopped rereading, maybe because I was surrounded by people who had read more than me.

Engelsing, Darnton writes, “does not produce much evidence for this hypothesis.” But the model maps nicely to my own reading life. As a child I read intensively, the same few books over and over. They weren’t world-historical or holy texts, but standard-issue YA, Louis Sachar and Judy Blume; books I came upon randomly, at bookfairs and in the strip-mall second-hand bookstore my mother took me to, or in the back of Waldenbooks or B. Dalton. A few were hand-me-downs from my mother’s own childhood (like The Boxcar Children). It was partly an issue of access—I couldn’t drive to the library myself or just buy more books whenever I wanted. I also found it comforting. Those books, like a song on a jukebox, produced a reliable feeling. Abruptly, in college, I stopped rereading, maybe because I was surrounded by people who had read more than me.

Some people say rereading is the only reading, but sometimes I think first readings are the only rereading. This isn’t total nonsense. First readings are when I pay the most attention, do the most doubling back. They’re when I have the most capacity for shock and joy. When I reread I am always comparing my experience to my first impression, a constant distraction; I am tempted to skip and skim, to get along with it and verify my memories already, my belief that I already know what I think. You can reread ad infinitum, but you can only read something for the first time once.

There are other anxieties. I’m running out of time to read all the books I want to, of course; of course my one life is getting on half over, if I’m lucky. But more so—it feels like people who urge you to reread books so you can form a new opinion, to update or overwrite the old one, want you to betray your younger self, as if the new opinion is better—as if my new self is better. Maybe I’m not any better? I think some books are better encountered when you’ve read less, lived less, and know less. You can’t wait to read everything until you’re wiser, nor can you already have read everything once. At some point, you just have to read things. I want to defend my fifteen-year-old self from that friend who said, “Read it again.” That self only knew what she knew. That self wasn’t wrong.

The summer I moved back to New England, after living in Denver for ten years, after living in Boston for ten before that, I decided to reread some books. Specifically, I wanted to revisit books from my youth, my deep youth—books that I dimly remembered, so they would feel almost like first readings. John and I went to the Book Barn, and I found one of those mass-market paperback copies of The Catcher in the Rye with the brick-red cover for a dollar. The copyright page says, “69 printings through 1989.” The one I read in the nineties was black type on white, with a rainbow of diagonal lines in the upper-left corner. I read it in my childhood bedroom in my parents’ house in El Paso, Texas, where I spent the first two decades of my life, where in high school I made a collage on one wall using magazine cut-ups and scotch tape. When I moved out, my parents took it down and repainted. This time, I read it in my mother-in-law’s house in Norwich, Connecticut, the house John grew up in. His old room still looks like the nineties. The wallpaper matches the bedspread.

“If you really want to hear about it,” The Catcher in the Rye begins,

the first thing you’ll probably want to know is where I was born, and what my lousy childhood was like, and how my parents were occupied and all before they had me, and all that David Copperfield kind of crap, but I don’t feel like going into it, if you want to know the truth. In the first place, that stuff bores me, and in the second place, my parents would have about two hemorrhages apiece if I told anything pretty personal about them.

I started the novel with some trepidation (what if I was wrong?) but quickly relaxed into it. Like Huck Finn, it’s mostly a voicey monologue, even voicier than I remembered, full of emphatic italics (“They’re nice and all—I’m not saying that”) and direct address, breaking the fourth wall. When Holden tells us about his little sister Phoebe he says, “You’d like her.” It’s a little bit dated and heavy-handed—if I read it for the first time in my forties, I probably wouldn’t like it as much as I did at fifteen. But how can I know? As Holden says, “How do you know what you’re going to do till you do it?” I can’t know, but I can see why I liked it—it’s not about some big subject that I couldn’t understand or didn’t care about, like so many “good” books I encountered at the time. It’s just about the experience of being young, or young but on the edge-end of youth, when you don’t fit in with kids anymore or adults quite yet. The stuff that happens in the novel, over several days, is mostly random and low-stakes. Like Huck Finn, it’s picaresque, and very funny.

I started the novel with some trepidation (what if I was wrong?) but quickly relaxed into it. Like Huck Finn, it’s mostly a voicey monologue, even voicier than I remembered, full of emphatic italics (“They’re nice and all—I’m not saying that”) and direct address, breaking the fourth wall. When Holden tells us about his little sister Phoebe he says, “You’d like her.” It’s a little bit dated and heavy-handed—if I read it for the first time in my forties, I probably wouldn’t like it as much as I did at fifteen. But how can I know? As Holden says, “How do you know what you’re going to do till you do it?” I can’t know, but I can see why I liked it—it’s not about some big subject that I couldn’t understand or didn’t care about, like so many “good” books I encountered at the time. It’s just about the experience of being young, or young but on the edge-end of youth, when you don’t fit in with kids anymore or adults quite yet. The stuff that happens in the novel, over several days, is mostly random and low-stakes. Like Huck Finn, it’s picaresque, and very funny.

I have a sense that I found Holden purely likeable on the first read, a sense that I was fully charmed. On this read he seems more unreliable to me, and a bad judge of his own character. It’s not necessarily a permanent character flaw. He’s grieving—we learn on page 38 that his younger brother Allie has died of leukemia (“You’d have liked him”)—and he’s depressed; he can’t see what bad shape he’s in. He’s a liar, which he knows, but he’s lying even when he doesn’t think he’s lying. The dialogue comes from inside the monologue, so how much of it can we trust? We get both halves of conversations through him. This book is often about the difference between what we say and what we think—Holden hates phonies, but when he talks to his old teacher, on his way to drop out of school, he says one thing and thinks another:

“Life is a game, boy. Life is a game that one plays according to the rules.”

“Yes, sir. I know it is. I know it.”

Game, my ass. Some game. If you get on the side where all the hot-shots are, then it’s a game, all right—I’ll admit that. But if you get on the other side, where there aren’t any hot-shots, then what’s a game about it? Nothing. No game.

He’s playing the game here, telling his teacher what he wants to hear. When Holden meets a classmate’s mother on a train, he starts “shooting the old crap around a little bit.” He tells the woman that her son is very popular, yet shy and modest—her son Ernest, “doubtless the biggest bastard that ever went to Pencey … He was always going down the corridor, after he’d had a shower, snapping his soggy old wet towel at people’s asses. That’s exactly the kind of guy he was.” Ernest’s mother agrees that he’s sensitive. Holden thinks, “about as sensitive as a goddamn toilet seat.” Holden pretends to be grown up—standing to his full height and showing off his premature gray so he can order drinks at a bar—but he likes kids more than adults. Kids are genuine, grown-ups are fake, and at the edge-end of youth, he hates what he’s becoming. Can you like Holden, as an adult? I can, but it’s different. I don’t admire him. He’s pathetic, in both senses—tragically pitiable and also kind of disgusting. He’s a “sad, screwed-up type guy,” like he says of Hamlet.  (Recently, watching a production of Hamlet, always surprised by how much the play contains, always more than I remember or seems possible, I thought: Memory is impoverished compared to experience—a good argument for rereading. But experience is richer than assumption or projection—a good argument for reading something new. I was surprised by the very first line I read of Proust.)

(Recently, watching a production of Hamlet, always surprised by how much the play contains, always more than I remember or seems possible, I thought: Memory is impoverished compared to experience—a good argument for rereading. But experience is richer than assumption or projection—a good argument for reading something new. I was surprised by the very first line I read of Proust.)

A little more than halfway through the book, Holden walks around Central Park in the cold, looking for his sister. (How did I picture the park as a teenager, before I’d been to New York City? I suppose I knew how it looked from movies. Manhattan, Whit Stillman’s Metropolitan, which made me feel—and this is how I put it to myself at the time, in these exact words—like I don’t exist, like Manhattan was the center of the universe and I was off in a distant arm of the spiral galaxy.) He remembers going to the Museum of Natural History almost weekly as a grade-school student. “I get very happy when I think about it. Even now.” He remembers the nice smell inside the auditorium—“It always smelled like it was raining outside, even if it wasn’t, and you were in the only nice, dry, cosy place in the world”—and the sticky hand of the little girl he was partnered with. “The best thing, though,” Holden says, “in that museum was that everything always stayed right where it was.” As many times as you went,

that Eskimo would still be just finished catching those two fish, the birds would still be on their way south, the deers would still be drinking out of that water hole, with their pretty antlers and their pretty, skinny legs, and weaving that same blanket. Nobody’d be different. The only thing that would be different would be you. Not that you’d be so much older or anything. It wouldn’t be that exactly. You’d just be different, that’s all. You’d have an overcoat on this time. Or the kid that was your partner in line the last time had got scarlet fever and you’d have a new partner … Or you’d just passed by one of those puddles in the street with gasoline rainbows in them. I mean you’d be different in some way—I can’t explain what I mean.

It’s too perfect to say, that’s like me, with this book. If I still like the book, I’m not fundamentally different, but I’m different enough to make a difference. Part of the difference is that I can articulate now what I understood then more instinctively—which doesn’t make the later reading experience better. In fact I feel like Salinger was writing for the inarticulate kid—he was writing more for me then than me now. I’m glad I read it first then, and whenever a friend says they’ve never read it, I tend to tell them it’s too late now. I don’t know if that’s true, because I don’t have the experience of reading it late, not for the first time, but I believe it to be true. I think I was right, at fifteen, to like it for the reasons I did. I wasn’t wrong.

In the park, Holden thinks about Phoebe getting older, being different—it upsets him. He wants to keep her innocent. Holden has learned early that life gets harder and worse. “Certain things they should stay the way they are. You ought to be able to stick them in one of those big glass cases and just leave them alone.” In this blue mood he meets his old girlfriend Sally, a phony, for a play, and then they go ice skating at her insistence. She wants to rent one of those “darling little skating skirts.” “That’s why she was so hot to go,” Holden says. “They gave Sally this little blue butt-twitcher of a dress to wear. She really did look damn good in it, though. I have to admit it.” For some reason this is one of the scenes I most vividly remembered through the years, Sally showing off her cute ass, and Holden barely tolerating Sally, finally insulting her and making her cry. A few chapters later, he sneaks into his parents’ apartment—they don’t know he dropped out of school yet—to see Phoebe. I remembered this part too. Out of all the scenes in the book, the ones that stuck with me were the ice-skating scene, and sexy Stradlater telling Holden about his date with Jane, a girl Holden had loved, agitating him unto violence, and then visiting Phoebe in her pajamas, and then the scene in the stairwell at Phoebe’s school, where Holden had also gone, with the “Fuck you” scrawled on the wall, which he tries to rub off. It’s the encroachment of the dirty, dark world of adults, inside this world of children, that disgusts him. “It wouldn’t come off. It’s hopeless anyway. If you had a million years to do it in, you couldn’t rub out even half the ‘Fuck you’ signs in the world. It’s impossible.”

All these scenes felt good to reread too, either funny or moving—intense moments of escape or transgression. I remembered these, and I forgot all the bad parts, the parts I guess that were supposed to jump out when I was told to “read it again.” I’d forgotten the really homophobic and misogynist stuff. There’s not a ton of it, but it’s there and I’d forgotten. It’s a gift when you can do that, when you can forget. I want to protect these good parts I remember, the parts I loved at fifteen and forty-two, to preserve them in their glass case. I think it’s beautiful, still, that Holden wants to keep the school children innocent, that he wants to protect them, because he can’t be protected anymore, he thinks. Like one of Rilke’s angels, he wants to protect kids from pain, from learning what life is like with its “Fuck you” graffiti everywhere. He thinks it’s too late for him, that he can’t go home and can’t go back to school. But he can still catch these kids—“if a body catch a body coming through the rye”—before they run off the cliff edge of youth.

*

John has a theory that everyone is either a squid or an eel. Baby squids are born as perfectly formed but teeny versions of their later selves. Eels go through radical changes over the course of one lifetime, to the degree that scientists used to think eels at different life stages were totally different types of eel. John claims he is an eel, and I am a squid. When we met, I’d sometimes ask him what he thought of one book or another, and he would say he didn’t know—he had read it, but ten or fifteen years earlier, and no longer trusted his opinion. Every five to ten years, he feels like a different self. Over the many years he’s known me, he says, I’ve been strikingly consistent. I think about this theory whenever I revisit a book or a movie, half-expecting my opinion to change, and find that I feel much the same: it’s the same river and I am the same man. I appreciate Hamlet much more than I used to, but it’s too long and some of it is boring. When I was bored during Hamlet as a kid, I wasn’t wrong.

I’ve been rereading books in part to test my squidness. Reading Catcher in the Rye reinforced my squidness, but made me overconfident. Next I started Breakfast of Champions by Vonnegut, which I adored at sixteen. I only made it through one chapter. “Trout and Hoover were citizens of the United States of America, a country which was called America for short. This was their national anthem, which was pure balderdash, like so much they were expected to take seriously.” It was too straightforward. I thought to myself, This book was written for children. Why didn’t I think that of the Salinger? Or why did I think the same, but not in a negative way? In The Child that Books Built, Francis Spufford remarks that reading Catcher as an adolescent, “usually you feel that he’s doing being a lost boy more completely than you.” You see the irony more as an adult—this is the artful double exposure of the book—but it works either way. Holden works as a character whether you envy or pity him. I sometimes think what makes a book a classic is that it’s appealing to young people, yet belongs to a grown-up moral world. I think great books engender a feeling of longing, something just out of reach. When you’re young, it’s the grown-up world out of reach; when you’re older, it’s the freedom of youth. Each looks like freedom to the other.

I’ve been rereading books in part to test my squidness. Reading Catcher in the Rye reinforced my squidness, but made me overconfident. Next I started Breakfast of Champions by Vonnegut, which I adored at sixteen. I only made it through one chapter. “Trout and Hoover were citizens of the United States of America, a country which was called America for short. This was their national anthem, which was pure balderdash, like so much they were expected to take seriously.” It was too straightforward. I thought to myself, This book was written for children. Why didn’t I think that of the Salinger? Or why did I think the same, but not in a negative way? In The Child that Books Built, Francis Spufford remarks that reading Catcher as an adolescent, “usually you feel that he’s doing being a lost boy more completely than you.” You see the irony more as an adult—this is the artful double exposure of the book—but it works either way. Holden works as a character whether you envy or pity him. I sometimes think what makes a book a classic is that it’s appealing to young people, yet belongs to a grown-up moral world. I think great books engender a feeling of longing, something just out of reach. When you’re young, it’s the grown-up world out of reach; when you’re older, it’s the freedom of youth. Each looks like freedom to the other.

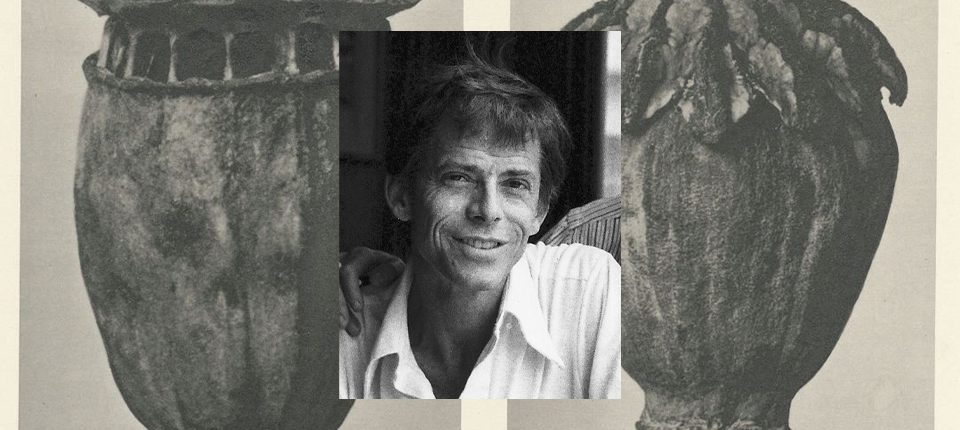

I decided to try Rabbit, Run. As far as I recall, I read it during my senior year of high school, and immediately felt it was my favorite book. I read the other Rabbit books in college, and a few more Updike novels in my twenties, but none of them struck me as much. Still, I have remained defensive of Updike—it seems like nobody likes him anymore, he’s become a laughable figure, and I’m protective of his old corpse. We went back to the Book Barn and I found a used copy, the trade paperback with a photo of a basketball on the cover—so lazy. (I told a friend how much I hated the cover, and he protested that it works because it’s about an aging athlete. “It’s not about a basketball, David,” I shouted, “it’s about lost youth!”) It was slow to get into, with meandering slow moody sentences, not written for children: “This farmhouse, which once commanded half of the acreage the town is now built on, still retains, behind a shattered and vandalized fence, its yard, a junkheap of brown stalks and eroded timber that will in the summer bloom with an unwanted wealth of weeds, waxy green wands and milky pods of silk seeds and airy yellow heads almost liquid with pollen.” There’s a smothering humidity to the prose. “Then, safe on the firm blacktop, you can decide whether to walk back down home or to hike up to the Pinnacle Hotel for a candy bar and a view of Brewer spread out like a carpet, a red city, where they paint wood, tin, even red bricks red, an orange rose flowerpot red that is unlike the color of any other city in the world yet to the children of the county is the only color of cities, the color all cities are.” And then here and there, amidst this thick damp description, a short clean sentence that’s like coming up for air: “There was no sunshine in it.”

I decided to try Rabbit, Run. As far as I recall, I read it during my senior year of high school, and immediately felt it was my favorite book. I read the other Rabbit books in college, and a few more Updike novels in my twenties, but none of them struck me as much. Still, I have remained defensive of Updike—it seems like nobody likes him anymore, he’s become a laughable figure, and I’m protective of his old corpse. We went back to the Book Barn and I found a used copy, the trade paperback with a photo of a basketball on the cover—so lazy. (I told a friend how much I hated the cover, and he protested that it works because it’s about an aging athlete. “It’s not about a basketball, David,” I shouted, “it’s about lost youth!”) It was slow to get into, with meandering slow moody sentences, not written for children: “This farmhouse, which once commanded half of the acreage the town is now built on, still retains, behind a shattered and vandalized fence, its yard, a junkheap of brown stalks and eroded timber that will in the summer bloom with an unwanted wealth of weeds, waxy green wands and milky pods of silk seeds and airy yellow heads almost liquid with pollen.” There’s a smothering humidity to the prose. “Then, safe on the firm blacktop, you can decide whether to walk back down home or to hike up to the Pinnacle Hotel for a candy bar and a view of Brewer spread out like a carpet, a red city, where they paint wood, tin, even red bricks red, an orange rose flowerpot red that is unlike the color of any other city in the world yet to the children of the county is the only color of cities, the color all cities are.” And then here and there, amidst this thick damp description, a short clean sentence that’s like coming up for air: “There was no sunshine in it.”

About fifty pages in I was wondering, why did I love this book about lost youth so much when I was young, before I’d lost anything? Did we know, a little bit, while still in youth, how precious it was? I was not very into the book, at that point. I couldn’t remember what I’d liked about it at seventeen; it gave me an eel-like feeling. On the page torn from a notepad I was using as a bookmark, I wrote: I am disappointed in Updike. I wish it was funny, at all. It was sometimes beautiful—I love that list of songs on the radio, the first time he runs away, that particular way of marking passed time—but never funny; somehow baggy, with too much fabric; and often so mean it’s repulsive. It’s Rabbit, Harry “Rabbit” Angstrom, that’s mean and not the novel, I think; I don’t think the novel is on Rabbit’s side exactly. We are not permitted to stay too close to Harry and side with him too much. But still, it’s hard to watch. That’s how it feels, that you’re watching him be mean to his poor wife Janice. Janice loves him, but she knows he’s vile. On page 80, he tells Ruth, the woman he’s just met that he’s about to shack up with, that he’ll run out for groceries and she can make them lunch. “You said last night you liked to cook.” “I said I used to.” “Well, if you used to you still do.” That’s a squid thing to say! The feeling of starting to like a thing I used to hate is pleasurable, I’ve noticed, but not the reverse. It’s a pleasurable kind of cheating, a bending of rules, as opposed to a betrayal of the whole system.

Around page 90, just when I thought I had seen enough and was about to stop reading, it suddenly got a little funny—as if wishes worked. Right around where Harry runs into Reverend Eccles, it suddenly got really good, the way the whole mood of a party can change when someone new walks in. I hadn’t remembered the character of Eccles, who takes an interest in Harry, who wants to save Harry’s marriage and be Harry’s friend. I think Eccles saves the novel. When Eccles’ wife asks him, “Why must you spend your life chasing after that worthless heel?” he responds, “He’s not worthless. I love him.” That’s Updike, I realize now—I don’t think I would have seen it back then. He loves Rabbit, the way God loves all his little sinners. It made me love him too—because I did love Rabbit at seventeen, as I’d loved Holden before him—this insistence that he deserves attention, that terrible people can still be tragic and worthy of love. There’s a complexity to the morals, and a sophistication to the point of view, that I have trouble believing I would have grasped on first read. Eccles does succeed in convincing Harry to return to his wife when she goes into labor with their second child. He’s so relieved to be forgiven, relieved that neither of them dies in childbirth, which would seem just punishment, that they spend a month or two in hazy bliss. The happiness here is a false bottom. He tries to seduce her one night before she’s ready. She feels used and turns him away. Angry, he gets up to leave again. “Why can’t you try to imagine how I feel? I’ve just had a baby,” she says. “I can,” he says, “I can but I don’t want to, it’s not the thing, the thing is how I feel.” When Janice wonders of Harry, after he’s gone, “What was so precious about him?” we understand it’s that he’s in a novel, because the novel’s about him. Updike, the God of this novel, can imagine how Janice feels—he understands why Janice drinks, the same reason Rabbit runs, for freedom. (She is stuck, either stuck with Harry or stuck alone, but a drink helps a little, it makes “the edges nice and rainbowy.”) He withholds that understanding, that ability or willingness, from Harry, so Harry can act as he does, selfishly, cruelly. So we can live vicariously through Harry’s escapes, and then see him punished for his mistakes.

I once read that we remember experiences by either their peak of intensity or what happens at the end—that people may forget the pain of childbirth, in the classic example, because it ends so happily. I wonder if that happened for me with Rabbit, Run. It was the tub scene I remembered most clearly, though I had a false memory of what she’d been drinking. (I thought it was Campari, but it’s whiskey. The Campari I must have imported from a later novel, maybe Rabbit Is Rich.) She starts drinking and I saw it coming, as I couldn’t have before, because I didn’t know anything about the plot the first time I read it. This time, when Janice turns the faucet on, I physically shook my head—don’t do it. The writing in this passage, too, is beautiful, so close we are to Janice, with Janice into morning as she tries to drink her fear away. “As she sits there watching the blank radiance a feeling of some other person standing behind her makes her snap her head around several times. She is very quick about it but there is always a space she can’t see, which the other person could dodge into if he’s there.” What is the presence, the ghost of Rabbit? Is it us? She keeps drinking, “just to keep sealed shut the great hole”—“she feels like a rainbow.” And when she loses her grip on the baby in the tub, “it is only a moment, but a moment dragged out in a thicker time.” The last line of this passage can almost make me cry, even read in isolation: “Her sense of the third person with them widens enormously, and she knows, knows, while knocks sound at the door, that the worst thing that has ever happened to any woman in the world has happened to her.”

I once read that we remember experiences by either their peak of intensity or what happens at the end—that people may forget the pain of childbirth, in the classic example, because it ends so happily. I wonder if that happened for me with Rabbit, Run. It was the tub scene I remembered most clearly, though I had a false memory of what she’d been drinking. (I thought it was Campari, but it’s whiskey. The Campari I must have imported from a later novel, maybe Rabbit Is Rich.) She starts drinking and I saw it coming, as I couldn’t have before, because I didn’t know anything about the plot the first time I read it. This time, when Janice turns the faucet on, I physically shook my head—don’t do it. The writing in this passage, too, is beautiful, so close we are to Janice, with Janice into morning as she tries to drink her fear away. “As she sits there watching the blank radiance a feeling of some other person standing behind her makes her snap her head around several times. She is very quick about it but there is always a space she can’t see, which the other person could dodge into if he’s there.” What is the presence, the ghost of Rabbit? Is it us? She keeps drinking, “just to keep sealed shut the great hole”—“she feels like a rainbow.” And when she loses her grip on the baby in the tub, “it is only a moment, but a moment dragged out in a thicker time.” The last line of this passage can almost make me cry, even read in isolation: “Her sense of the third person with them widens enormously, and she knows, knows, while knocks sound at the door, that the worst thing that has ever happened to any woman in the world has happened to her.”

Eccles’ wife says, “You never should have brought them back together”—implicating him. Eccles calls Harry and tells him, “A terrible thing has happened to us.” That us is Eccles and Harry, Eccles and God and Harry—or author and character, author and reader. We’re all in this mess together, we all murdered the baby. In the aftermath Harry seems to almost know, to finally know, he’s been in the wrong—“He feels he will never resist anything again”—but he can’t quite know it, because what held him back from going home was “the feeling that somewhere there was something better for him.” Something better, that is, than settling down with the first woman he got pregnant, who is likewise forced to settle for him; something better than a job on his father-in-law’s car lot, when he used to know the glory of the court. This is the complexity I mean, this teetering refusal to side quite for or against Harry Angstrom. The choice between freedom and duty is not an easy choice, the book allows, not actually. And it’s not a question of fairness. That wanting more than life usually offers is somehow evil—this is a tragedy.

It’s not at all like I remembered, I kept telling people, when I mentioned I was reading Rabbit, Run. But really, I remembered barely anything about it. Just a couple of scenes—that first time in the bar, drinking daiquiris, with his old coach and Ruth, and the bathtub—and the general idea of lost youth. And it’s not lost innocence. Youth isn’t innocence, it’s possibility.

Excerpted from Any Person Is the Only Self: Essays by Elisa Gabbert. Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Copyright © 2024 by Elisa Gabbert. All rights reserved.