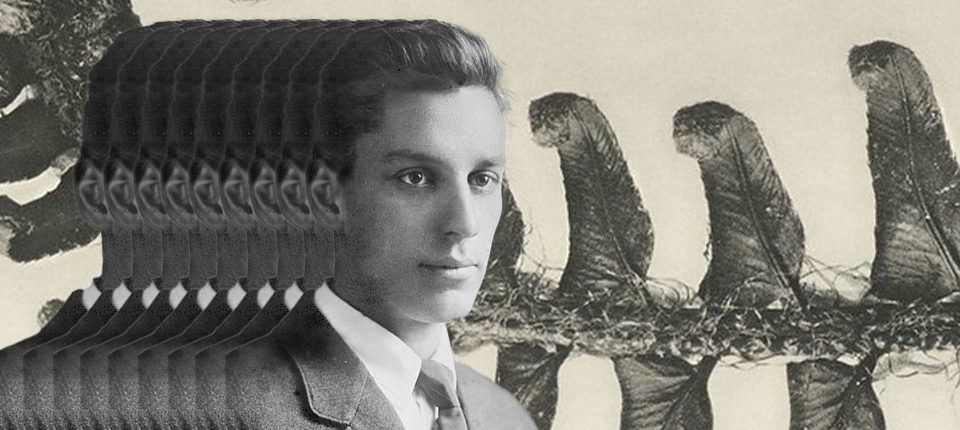

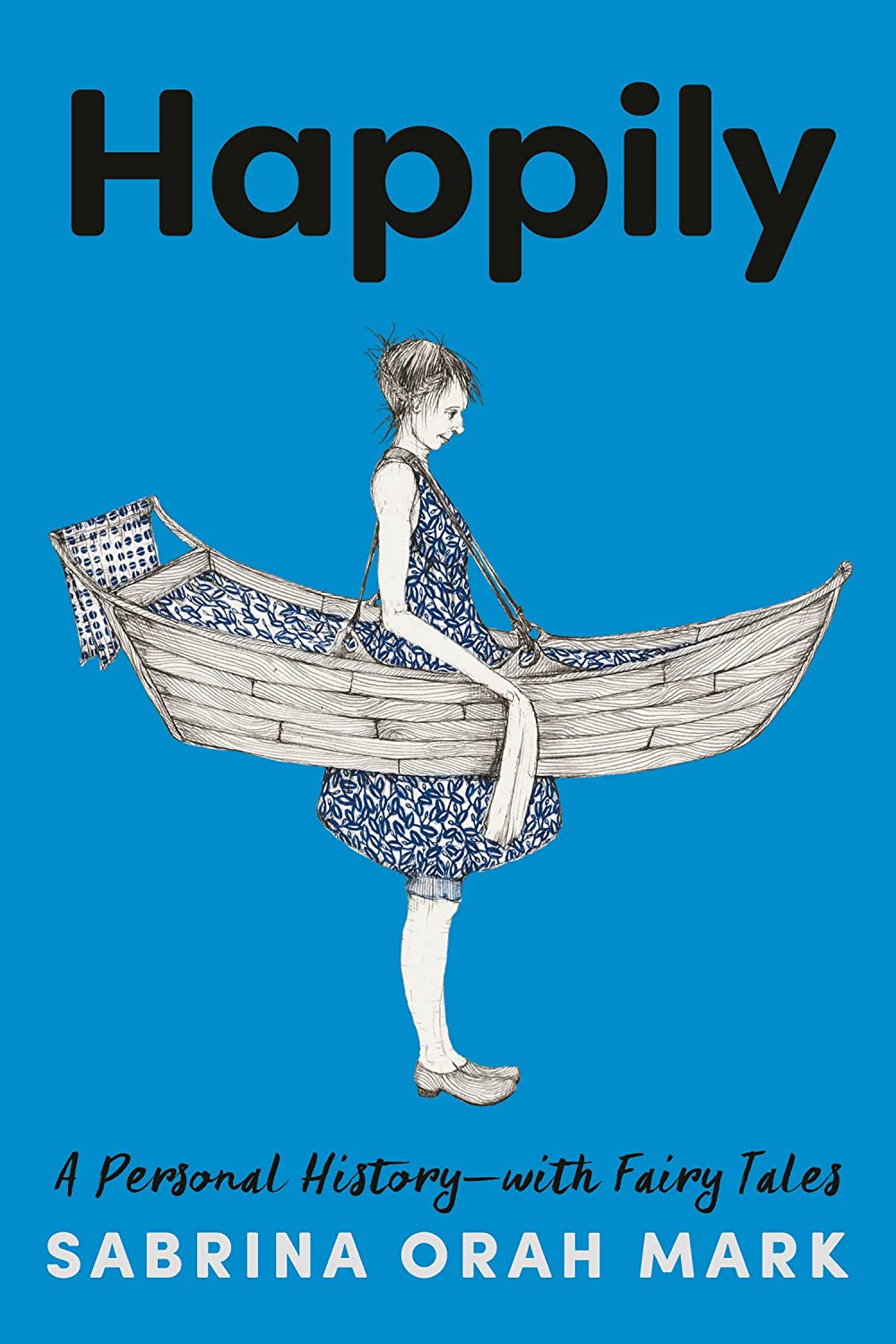

On the surface, the subtitle of Sabrina Orah Mark’s new memoir-in-essays Happily—”A Personal History, With Fairy Tales”—seems contradictory. How can a narrative be simultaneously true and imaginary, historical and fantastical?

The 26 essays in Happily—drawn from Mark’s Paris Review column of the same name—deftly achieve this feat. Filtering her experiences as a mother and daughter, wife and sister, friend and artist through the lens of fairy tales, Mark illuminates the lasting power of folklore to illuminate truths about the human condition. Whether meditating on her feelings of kinship with the archetypal stepmother, grappling with her experience as a Jewish woman raising Black sons in Georgia, or connecting the dots between Rapunzel and her sister’s physical changes during chemotherapy, Mark plays with the boundaries between the mundane and the magical. The age-old tales of Western culture become windows through which she shows readers the world anew.

I spoke with Mark about the allure of the sonnet, the ethics of writing about one’s children, and how her Yeshiva education shaped her sensibilities as an author.

Nicole Graev Lipson: I’m curious about the origins of your interest in fairy tales. They loom so large for us as children, but there’s an assumption that, over time, we outgrow them. What is it about fairy tales that strikes such a deep chord with you?

Sabrina Orah Mark: As a kid, I don’t think I ever really read fairy tales. My interest began when I went to see the Bruno Schultz murals at the Yad Vashem Holocaust Remembrance Center in Jerusalem, where there were these fragments of fairy-tale scenes emerging from the whitewash. I remember looking at them and thinking: That’s what I want to do as a writer. I want the ancient and the new to collide into a single moment.

Writing Happily was really about two things. One part was remembering. For instance, my little one said to me one day, “I’ll teach you how to button your sweater for when you’re young again”—and I thought to myself, Okay, if I don’t write that down, I’ll never remember that. But the other part was really terror. It was like: Here I am. I live in Georgia, raising Black Jewish boys. What have I done here? As my kids began school and were out in the world more and more, I started writing these essays out of an impulse to keep them safe, as if by writing a story around them I could protect them. I think I needed some kind of mystic to go to, and it was the fairy tale that emerged and reached out its hand to accompany me on the journey.

NLG: Your Orthodox Jewish upbringing and Yeshiva education are an important backdrop to Happily. I’m curious if studying the stories of the Torah as a child shaped the way you see the world as a writer?

SOM: A hundred percent. I didn’t read fairy tales as a child, but I read the Old Testament every day, and studying Torah is like studying fairy tales. I read every story about apocalypse and miracle, and to me, the miracle was real, because the Torah was a book of things that had happened that was written by God. When we study Torah, the line between what’s a miracle and what’s real is so blurred. If that’s your first interaction with storytelling, of course all your boundaries are going to be blurred. As far as I was concerned, Lot’s wife turned into a pillar of salt. Of course she did, because that’s history.

The Torah is also a world filled with questions to which there are no answers. The not-knowing is central to how I think about writing a story or an essay. The essay is a search for knowing, while always being in a realm of unknowing.

NGL: In the essay “Ever After” you write, “In fairy tales, forms can unbutton like overcoats, drop to the ground and vanish without a trace.” It occurred to me that this could be a description of your writing style. These essays have a beautiful evanescent quality about them, with images that dissolve and morph in real time. Was this effect intentional?

SOM: As an undergraduate, I spent a lot of time writing sonnets, and I loved traditional forms. Over time, the sonnet kind of grew inside of me and turned into a prose poem. I wrote two collections of prose poems. Then, after I had my kids, I think I just became a more porous person. It was like the prose poem couldn’t hold. It had to be constantly interrupted.

The form of the fairy tale is pretty hermetically sealed. You have the “Once upon a time,” and then you have the “Ever after,” the way you would end a sonnet with a couplet. I liked the idea of an essay almost forgetting, halfway through itself, that it’s an essay and needing some kind of fiction or poetry inside of it. I love that kind of shape-shifting, which we learn how to do inside fairy tales, where the beast turns into a man or the man turns into a beast. If I was using a less sealed form to trouble the idea of form, I think there would be too much formlessness. Once you have the borders, the box, you can go completely wild inside of it. There’s a sort of clarity to the wildness that I don’t think you can get in a less bordered space.

NLG: At times in the book, you wrestle with what it means to weave real-life loved ones into your writing. Sometimes I wonder just how many mothers out there have silenced their own truths out of fear that voicing them would violate their relationship with their children. Do you think about this, too?

SOM: When my kids were younger, it felt as though the things they said were part of a shared weather. Now, as they’re getting older and separating from me in certain ways, I’m very aware that their private lives are forming. There are things I just know instinctively I shouldn’t write about, things that don’t belong to me. There’s a difference between keeping privacy and silencing myself. I know how it feels in my body when something is silencing me, when I’m not writing about something that I should be. Whereas when I’m writing about something that’s not mine to write about, it doesn’t work. I think this is because it’s not my story. It’s somebody else’s story.

NLG: Motherhood is a prominent theme in Happily. You explore mothering your two sons, your relationship with your teenage stepdaughter, and your relationship with your own mother. How have fairy tales guided your thinking about motherhood and step-motherhood?

SOM: To speak to the stepmother part of things: I love my stepdaughter very much, but being a stepmother is very challenging. It comes with all the responsibilities of being a mother without the claim to being a mother. So you’re both the mother and the un-mother, and you’re always a reminder of the mother who isn’t there and all the feelings that absence brings up. I was scared of writing about this relationship because already there’s sense of walking on eggshells and not being allowed to say the things that you are feeling on both ends. This is where the fairy tale helped, where it reached out its hand. In this case, it was the wicked stepmother reaching out her hand and saying, Anything you do or think or feel would never be as horrible as what I have done.

One of the wonderful things about the fairy tale is that it thinks your most horrible thoughts and does your most terrible things. If you feel jealousy, it brings the one you are jealous of into the woods so that the woodsmen can cut open the one you are jealous of and take her heart. Bruno Bettelheim talks about this in terms of why fairy tales are so important for children. They act as these kinds of objective correlatives, where we can say, I am so scared my mother will one day disappear or abandon me, or I will be lost in the supermarket forever. They give us a container to hold all our feelings.