Revenge of the Mall Escalators

Escalator Mechanic

For Pablo Katchadjian

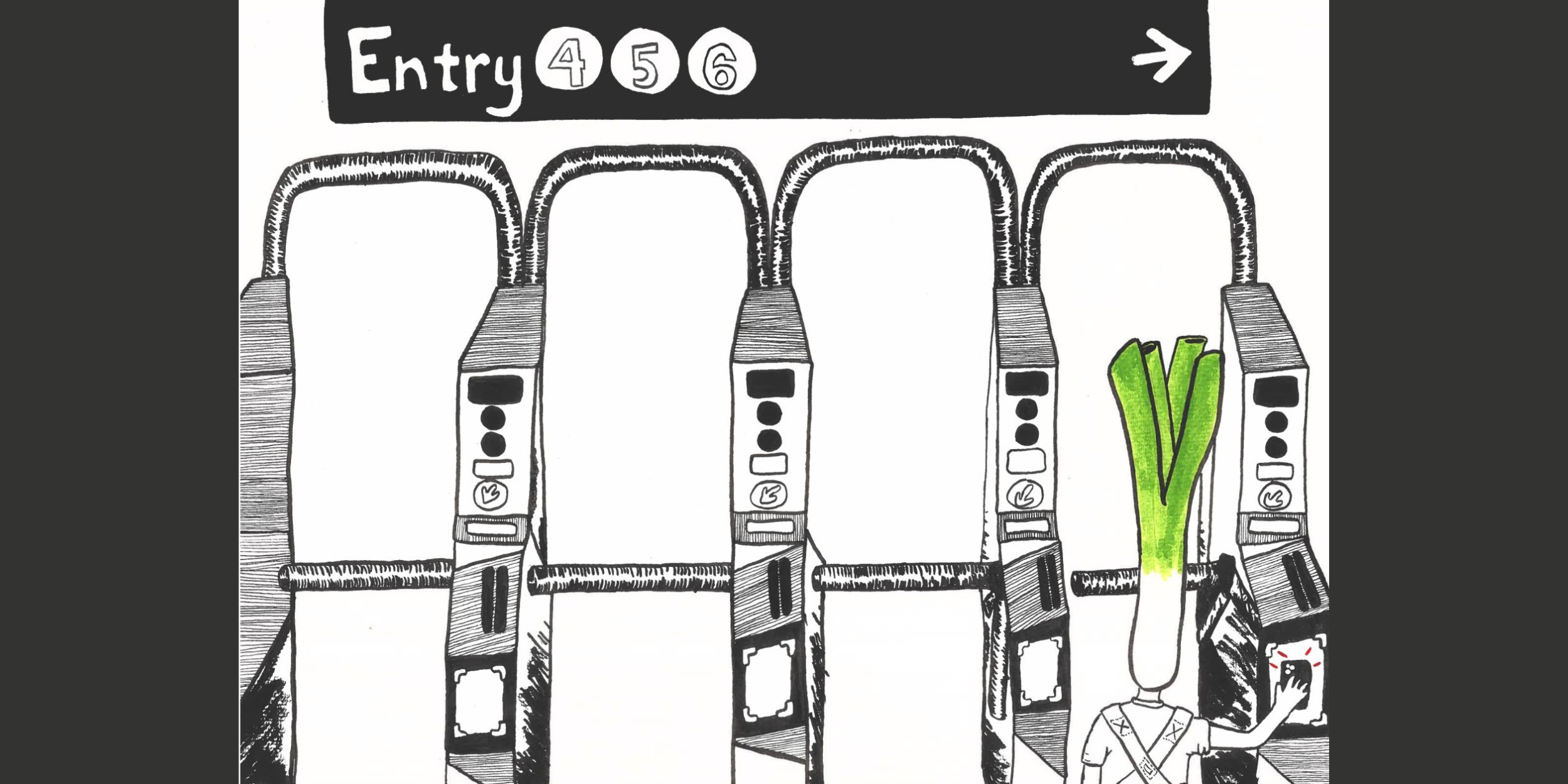

“For weeks I haven’t been able to focus on even the most trivial thing, because all I can think about is the shape of my right foot,” the escalator technician confessed to me. He was clocking out of work. “Look at those escalators I was supposed to be servicing. They’ve all gone haywire, completely insane. Some of them slice the soles off their passengers’ feet when they arrive at the landing. Some of them throw people straight off, like catapults. And others . . . others . . . don’t even move at all . . . .”

I didn’t know what to tell my friend, except that perhaps, for the sake of everyone’s safety, he should take some time off, go to the beach a week or two, relax, and let someone a little more competent—no, more composed—take his job for a while.

“But if I go to the beach, then I’ll have to swim, which means I’ll have to take off my shoes . . . and that will make everything worse. I don’t want anyone else to see it . . . I don’t even want to look at it myself.”

To be honest, I was confused. Looking at his shoe I found no obvious peculiarities. So I asked him what about his foot had him so captivated, so afraid. He sighed, and told me not to worry. After all, he said, it wasn’t my problem, and he didn’t want to make it so, for fear that, once involved, I would, like him, never be able to extricate myself from what he referred to as his “curse of distraction.”

A week later I was back at the mall, and everyone was in a huff because the escalators still weren’t in working order. Those with wounded feet had left their few bloody footprints and collapsed. Bodies trebucheted from the escalators were strewn in heaps across the three floors of the mall. Impromptu medical camps had begun tending to the survivors. Shop owners on the upper levels were organizing in protest because they hadn’t had any customers for weeks: the shoppers could only buy goods from the first floor, and besides, hardly anyone dared enter the mall anymore for the carnage. And people of all stripes, united in rare fashion, were blaming the escalator mechanic.

But this mechanic was no happy exception to the unhappy rule. Indeed, he may have been the most miserable of them all. And he took me aside, clearly in a desperate mood:

“I need someone else to know. I can’t handle this alone anymore.”

Out of sheer curiosity, I assented.

Upon my saying so, the man began to unlace his shoes, which, given the rawness of his grated soles, peeled off with great pain. Now, what he produced from underneath that leather Lovecraft himself would surely have described as ineffable, inarticulable, rapturously grotesque beyond language. But I’m not one to balk at a chance to dig into what others might find disgusting. In fact, I relish it. So, as much as my descriptions may inspire horrific images in your mind, please foreground, even before these images, the great pleasure I derive from relating them to you.

Out from the shoe first came the lower shin, which, transparent like a beer bottle, contained a brown, semi-boiling liquid that resembled—and smelled of—fermented apple cider. Through an opening in its side flew the hordes of fruit flies which, because of an inverted cone produced by the filth inside this cylinder, could not escape once they had entered. As a result, the ankle, which emerged next, was stuffed ever more densely with these insects, alive and dead, and I could not help but fear that its skin, which resembled a dun plastic shopping bag, would soon burst, releasing into the world some unseen and authentically dangerous illness. Out came the heel then, which at first glance seemed a miniaturized waterfall of incredible beauty, but soon revealed itself to be a poached ivory tusk of the recently extinct black rhinoceros, covered in a thick, steamy, oozing coat of Hollandaise sauce. The last thing to produce itself from that shoe was a broken web of muscles and veins, which dangled from the heel to the floor, and a head of hair wetted with spray adhesive: it swung freely, and yet remained bunched together by the congealing fluid it expelled. The flesh of his toes, he claimed, he had lost long ago in some other shoe, as well as their long bones, which once had traveled over the arch of his foot. The entire body part hung there at the end of his leg, pulsing like a heart, expanding and contracting like a lung, the rising and falling of Nature herself, and he looked between it and me through the spaces between his fingers, which covered his petrified face, anticipating the criticism he had feared so acutely those past few weeks.

I was speechless. My words prostrated in silence before my sense of awe.

“It’s . . . a work of art,” I whispered.

“I don’t . . . .” muttered the escalator mechanic. “It doesn’t disgust you?”

“No, not at all . . . not one bit!”

“But . . . .”

“Come to my house,” I pleaded. “Please, come to my house. I need to photograph you.”

“What? So everyone will know?”

“No, you fool!” I cried. “Because your foot makes me feel something. And I can’t say the same about many things anymore. How jaded I’ve become! Ever since childhood, I’ve been going along having these things we call experiences—each of which acts, at first, like a key to the next one that comes along and resembles it at all, and, later, like a blind that lies over it. That’s to say, if I haven’t already experienced something in itself, I’ve surely experienced something like it, and the similarity sits there like a lead blanket between the X-ray of my perception and whatever’s going on around me. I’m numb . . . completely numb! . . . Am I making any sense?”

“Mmm . . . I can’t tell.”

“All I mean to say is that I’ve never seen anything like your foot before . . . and it’s liberating, absolutely freeing, to see something entirely new.”

“Well, it couldn’t be entirely new. You just spent a page crafting ridiculous metaphors and similes comparing it to other things you’ve already seen. You’d have been more correct to, per Lovecraft, throw in the towel and call it indescribable, related to nothing, to no word, to . . . .”

In the meantime, the crowd had grown emotional to a point of total incoherence, dragging the escalator mechanic into its bloodthirsty ranks, and the author of this story drunk to such an extent that he is unable to continue writing, viewing his effort—for the time being, anyhow—as a tedium and a failure.

Excerpted from Cartoons, out May 21, 2024 from City Lights Books.