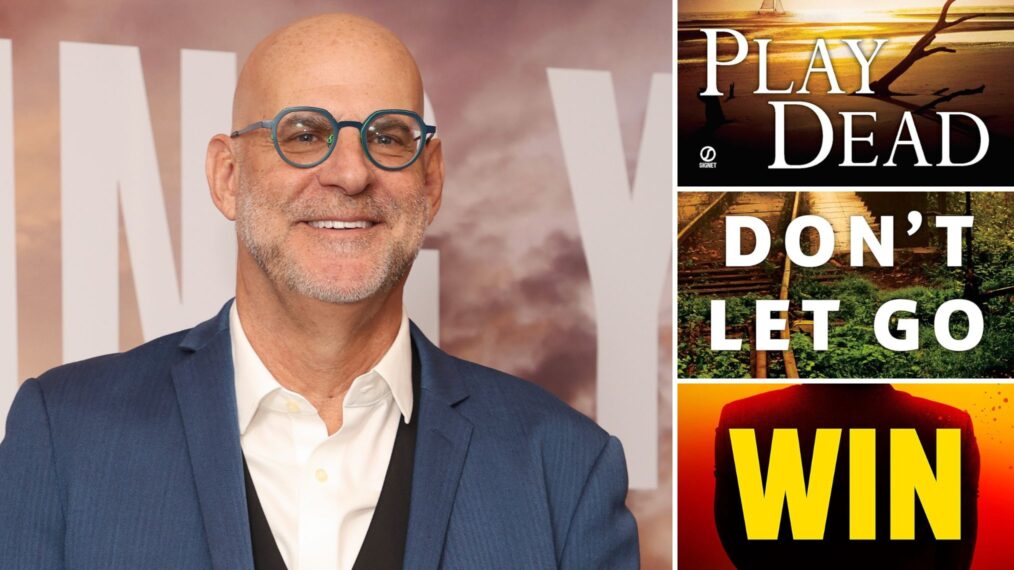

The first graphic novelist to be nominated for the Booker Prize, Nick Drnaso possesses an uncanny ability to tap into the bleak, nihilistic undercurrents of American culture, and to depict these undercurrents just before they swirl to the surface. Zadie Smith called Sabrina, Drnaso’s Booker Prize-nominated novel, about the distressed, grieving boyfriend of a murdered woman, “the best book—in any medium—I have read about our current moment.” In the wake of his girlfriend, Sabrina’s, killing, Teddy falls prey to the lies of an Infowars-style radio personality. Drnaso has long lurked in the darker corners of the internet, listening to, and discerning the appeal, of figures like Alex Jones before most knew who he was. Since its publication in 2019, Sabrina has only become more relevant.

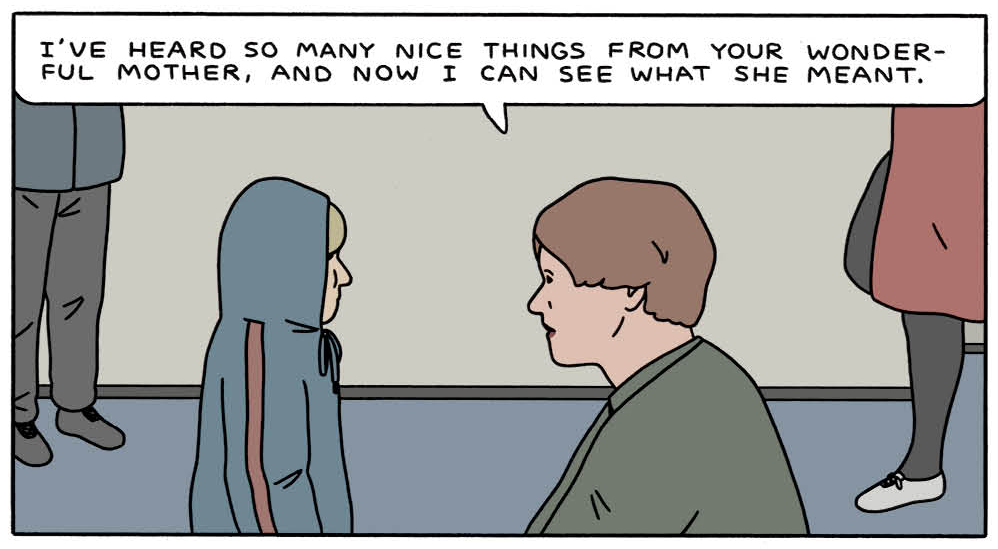

Acting Class is Drnaso’s third book. Less overtly political than Sabrina, Acting Class nonetheless resumes Sabrina’s preoccupation with the unnerving appeal of charlatanism in a nihilistic, alienated age. The ten characters, who enroll in the same evening acting class, are loners adrift in a bleak, colorless world: Drnaso’s drawings exhibit a dull, flat sameness that bespeaks internal landscapes of emotional numbness.

The class, led by a dynamic, seemingly compassionate man named John Smith, jolts the participants out of their listlessness. The method-style acting exercises are spontaneous and cathartic. Thomas, a ponytailed man who works as a nude model for figure-drawing classes, reenacts a crushing experienced of being fired from a job. Rayanne, an anxious single mother, assumes the role of a woman who’s just had her young child taken away by child protective services. Rendered vulnerable by these off-the-cuff performances, the participants begin to bond.

But John and his class are not what they appear. Bit by bit, we sense something is amiss. Angel, a lonely young woman, disappears for days, then turns up disoriented. Beth, another young participant, suffers a psychotic break. Slowly, the characters descend into a world from which they will not emerge.

I spoke with Drnaso, who is soft-spoken and self-deprecating, about the ways in which Acting Class captures our present moment, the dangerous appeal of gurus like John, and whether Drnaso would ever take an acting class.

Carli Cutchin: Acting Class reminded me at first of the HBO show Barry, where a hitman takes an acting class that leads him to want to reform. Then, as I read on, it reminded me of the Hulu series Nine Perfect Strangers, where Nicole Kidman plays a retreat center guru who drugs her unwitting subjects and pushes them to the edge in the name of self-awareness and personal growth. In both shows, the characters do walk away having experienced a kind of catharsis. Even while it leads to dangerous places, I thought there was a lot in John’s class that was pretty appealing; it almost made me want to take a similar class. I’m not sure what that says about me! Let’s talk about that appeal.

Nick Drnaso: I think I was trying to keep things in that gray area. That seemed like the best route, as opposed to clocking John as clearly as a bad person, or the villain of the story. I rode that line throughout the entirety of the book. John is acting in bad faith at times, but there’s not a moment where the mask comes off and he gives away the game.

Also, I wanted there to be some air of believability to these ten random people who have no [professional] stake in this class. They’re not interested in pursuing acting professionally. They’re just directionless and bored. And if things were pushed too far into something that’s explicitly abusive, they would probably all get up and leave. As you said, I tried to put in these [elements] that suggest that John is actually good at reading these people very quickly and sizing them up and pinpointing what they need, or what they think they need. Which is probably a skill that gurus and cult leaders and charlatans and con men have.

CC: D. T. Max, who profiled you in 2019 for the New Yorker, pointed out that while most young cartoonists focus on either the intimate (memoir) or the faraway (fantasy), your work has much in common with the traditional realist novel: “imaginary people experiencing the small conflicts and successes of ordinary life.” As with the 19th-century realist novel, Acting Class portrays a plethora of characters moving through what at least looks like ordinary life. But, as we discover, in this acting class, little is as it appears. It’s as if you’re interrogating the Real—what is authenticity, what is a mask?

You’re mirroring the behavior of your peers, or what’s socially acceptable.

ND: Acting Class was rooted in different circumstances I’ve found myself in. That kind of tweaking of your true personality or leaving your true personality at the door and assuming some kind of role in the group. I’ve always been interested in how that happens. Where I grew up [in suburban Chicago], and the kinds of people I grew up, that shaped my behavior. Once I moved out on my own and found a more like-minded group of people, I was able to express things that weren’t acceptable [growing up]. Those themes started to come out in Acting Class.

CC: When you were growing up, you were acting a lot of times?

ND: You’re mirroring the behavior of your peers, or what’s socially acceptable. Being casually religious, and going to mass, going to catechism, and really not feeling the Spirit so to speak. Knowing I’m not absorbing this. But you can’t express that yet. Feeling like everyone else seems to be on board, or relatively content, and feeling like I’m the problem in this equation.

CC: So then there’s a scrutiny of your own place in the social world?

ND: Yeah.

CC: I can relate to the sense of being frustrated that interactions stay on the surface a lot. Growing up, I was an only child and homeschooled; I was a little bit more isolated than the average kid. I’ve always longed to go deeper with people. I’m not as good at small talk. Sometimes it’s necessary to remain superficial, obviously. But there is this level of superficiality and artifice that happens especially in American social interactions. In America, you’re supposed to be authentic, but things remain shallow.

ND: That was pretty much my upbringing and the cultural norms of suburban Chicago. I felt like it was performative; the topics of conversation were narrow. I can think of instances where I would relate something to somebody and just get a blank stare. That kind of crushing, lonely feeling. In Acting Class, I imagined there being a thrill in making yourself vulnerable. Maybe that’s the appeal of performing for a lot of people.

CC: You told Granta that you have not, and never will, take an acting class. But if, in an alternate universe, you were to take one, what do you think you might discover about yourself?

The core of the storyline [is the theme] of moving toward something that alleviates pain, or displaces pain onto something else, or temporarily puts a band-aid over it.

ND: It would take a lot [to get me to take a class]. I would have to strip away layers and layers—a lifetime of self-criticism and pure self-loathing. I imagine [there’s a] thrill of being an entertainer, using your voice and your body and your emotions to entertain somebody and transport them. I love seeing somebody who’s transcending and giving a truly great performance. It’s inconceivable to me, [that I would] be that person. If I was forced at gunpoint to go to an acting class, I don’t know what I would bring to that.

CC: I get that. Is there, though, a character in Acting Class that you most relate to?

ND: Angel, the character who is maybe least comfortable in her own skin, and vaguely stumbles into the class, and has a lot of baggage of self-consciousness. John recognizes [her baggage] pretty quickly. She’s maybe the most willing participant in the class; I’d like to think I’d be more skeptical or more of an outsider like Rosie, who’s watching [the class] with the reader’s sense of skepticism. But I kind of wonder, if I was in a situation like that, where a guru or leader was able to alleviate some of my personal problems or mood disorders, if that would feel so great I would get completely sucked in—[would I] just go along with the person who’s making me temporarily feel better?

CC: It’s a frightening thought, right? And that reminds me of radio personality in Sabrina, this kind of Alex Jones character who appeals to grieving Teddy. Teddy is looking to have his overwhelming grief and rootlessness in the world alleviated. And he hears this radio personality and believes his conspiracy theories. In fact, this happens all the time on a socio-political scale.

Since 2019, Sabrina’s themes have become increasingly, unnervingly relevant. For example, I’d never heard of Alex Jones until the recent trial, where a jury found he must pay nearly $1 billion in damages to Sandy Hook families for falsely claiming they were actors who staged the tragedy. And here he—or someone who resembles him—is in this book you began writing many years ago. Since Sabrina’s publication we’ve also had the Covid-19 pandemic; we’ve seen increasing social unrest and a growing number of mass shootings. Have you sort of looked at everything going on and said to yourself, Yep, I was on to that?

ND: It’s a bad sign if the world is starting to seem more closely linked to my comics.

I’m preoccupied with the negative side of things, with bleak subject matter. When I started Sabrina, in 2014, Alex Jones was a pretty marginal figure; Trump hadn’t even announced his candidacy. As far as the broader theme of moving toward something that alleviates pain, or displaces pain onto something else, or temporarily puts a band-aid over it—it’s at the core of the storyline in Sabrina and a big part of the storyline in Acting Class. There’s an appeal in that kind of story—the idea of some kind of supernatural transformation that I haven’t been able to figure out in my life. [For me] it’s more of a matter of dealing with things, and maybe seeking out things to help. But it’s fun to play with a storyline where that transformation is surreal, like the way Angel has an almost spiritual awakening.

As we’re talking, it reminds me of talking to a friend years ago. He went to a Trump rally leading up to the 2016 election. He described the almost primal release in the crowd. People almost seemed high, like they were in a daze of excitement. The promise of something. There was a visceral feeling [at the rally] that he said was disturbing.

CC: I honestly found it a little difficult to distinguish the characters in Acting Class from one another, since, in your characteristic style, there’s a kind of uniformity and flatness to the figures. As a reader, there’s a certain amount of labor required to tell everyone apart. But this labor strikes me as deeply connected to the themes of Acting Class. It’s as if you’re reminding us that everyone wears a mask. Was this convergence of form and theme deliberate?

ND: When I’m writing I’m thinking creatively and narratively, but once I get to the drawing and plotting out the pages it’s just purely practical and pragmatic. My drawing style always tends toward what you described as expressionless sameness. The characters look kind of dull-like. And for this book maybe it did require a bit more than I put into it. Sometimes you can get lost when you’re not getting that immediate feedback from a reader that the characters look too similar, and that they need just a few more small markers, facial hair or a different body type.

CC: I don’t mean it as a criticism—from a formal perspective, it’s really interesting! Your drawing style raises questions of, “What is a mask?” “What is authenticity?”

We’ve talked about catharsis, about how John’s class seems cathartic at first. I’m wondering if drawing and writing play this role for you. In creating these books, are you able to work out the issues of loneliness or alienation you mentioned?

ND: I sometimes lose sight of that, because [making art] is an automatic routine that’s constant. At this point in my life, I’m constantly working on comics and art. The daily process of working is therapeutic in its own way. Working in fiction and trying to find an outlet for thoughts that are bouncing around makes [the thoughts] slightly more manageable. It doesn’t make them go away completely. Unfortunately, having the book out isn’t very cathartic. It’s nice when I hear someone say something about enjoying the book. But it’s hard to internalize those things. By the time a book comes out, I’m mostly just panicking about what the next [project] is going to be.