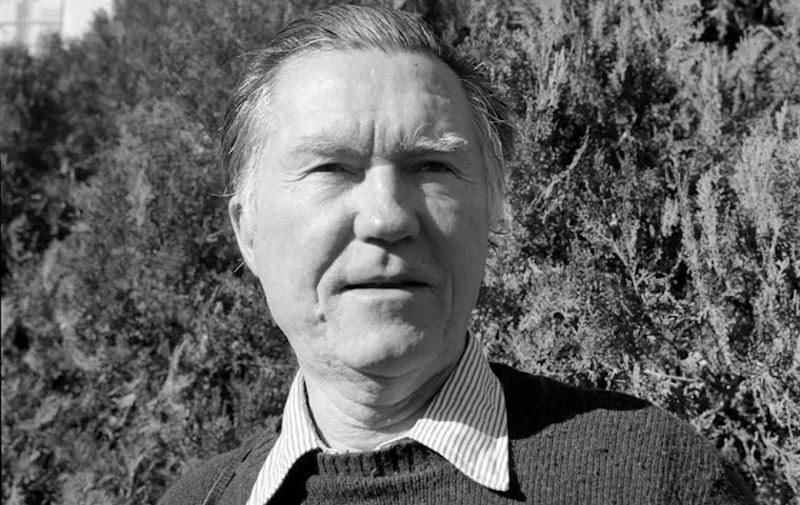

Early on the morning of August 28, 1993, the poet William Stafford scratched out the draft of a poem, as he did most mornings, while lying on the couch beneath the living room window at his home in Lake Oswego, Oregon. Later in the day, he sat at the cluttered desk in his writing room, a converted garage, where he typed out a book review and answered a few incoming letters. Then he took a break, called into the kitchen by his wife, Dorothy, to help clean up after a blender eruption. Perhaps he was also thinking of going out that evening to a party. We will never know. Stafford fell to the kitchen floor and died of a heart attack. He was 79 and still riding a wave of popularity—as much as poets in America can ever claim—that spanned three decades.

Stafford, who had served as Poetry Consultant to the Library of Congress (now known as the U.S. Poet Laureate) and as a longtime Poet Laureate of Oregon, was a transplanted Kansan. Memories, imagery, and echoes of his prairie and small-town roots permeate his poems.

He was a democratic poet, with a small “d,” suggesting that anyone could write poetry if they broke free from internal restraints.

Looking back on his life, as I’ve been doing in recent years, unearths not only a wealth of poetic charms but a sense that Stafford projected a moral force that can be useful if not essential today. His work threaded through concerns about the environment, race relations, politics, history, spirituality, and the depths and limitations of the human heart. As his friend the late Robert Bly said soon after Stafford’s death, the poet would be more widely read in the 21st century than he had up till then. (And his readership and popularity by that point was already considerable.) Bly recognized that Stafford would endure because of his life of peace-making. In life as in his poetry he rejected loud conflict and social and political aggression. Let’s be reasonable and gentle with each other. Let’s greet the world with awe and an impish sense of humor. Let’s be honest with one another, as in this line from a startlingly blunt poem, “Entering History,” first published the year Stafford died: “Minorities, they don’t have a country/ even if they vote: ‘Thanks, anyway,’/ the majority says.”

Stafford lived what he preached. He was a lifelong pacifist. When the United States entered World War II, following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, and called young men to serve, Stafford chose an alternate path. While a graduate student in literature at the University of Kansas, he registered as a conscientious objector to the war—to all wars—and accepted the consequences. Many Americans regarded COs as “slackers” and “yellowbellies,” but Stafford and about 12,000 other men took the barbs as they went about the business of forestry, soil conservation, hospital staffing, and other laboring tasks assigned to those encamped in Civilian Public Service operations around the country.

Stafford found love and marriage while in the CO camps of California. After the war, he furthered his efforts toward writing and settled into a career as a teacher at Lewis & Clark College in Portland, Oregon, where he taught for thirty years. His poetry made the pages of prominent magazines of the day, but it wasn’t until 1960, when, at the age of 46, his first book appeared in print. West of Your City, published by a small California press, was a kind of philosophical rejoinder to the likes of Robert Frost, the New England sage. Despite a press run of only four hundred and fifty copies, the book gained Stafford notice, including an admiring assessment from Sylvia Plath, who included him in a compact British anthology of contemporary American poets.

Less than three years later, in March 1963, Stafford came out of seemingly nowhere to win the National Book Award in Poetry for his next book, Traveling through the Dark. That book’s title poem—often referred to as the famous “dead-deer poem”—remains one of the most anthologized verses of the past half century. With its arresting, narrow-road presence, its round-the-campfire language, its comforting though hardly nostalgic tone, “Traveling through the Dark” shone its headlights on a swerving pathway through the wilderness and the world.

Stafford became a globe-traveling, campus-circuit-riding ambassador for poetry. His manifestos and conference planning on behalf of the National Council of Teachers of English coincided with the rise of poetry-in-the-schools programs and the expansion of college level writing workshops and MFA degrees. The wandering poet had a revered status as his practice grew and grew in the 1960s and beyond: He had the power of sprinkling aesthetic stardust on impressionable, open-minded students and aspiring talents. During the era of the Vietnam War he aligned with the anti-war poets but preferred the quiet jousting of verse to the stridency of public protest.

Some critics thought Stafford published much too much. What they miss is Stafford’s generosity and willingness to send out poems to any small or start-up journal editor who asked. He published eight books with Harper & Row in his lifetime and dozens more with an armada of fine printers and boutique presses, each of them fortunate to have his name on their lists.

After his death, the New York Times obituary, unsurprisingly, remembered him as a “regional poet.” As Stafford would often say in rebuttal to such diminutive judgments, in the United States “a national poet is a regional poet who lives in New York.”

Stafford eschewed labels. He was a democratic poet, with a small “d,” suggesting that anyone could write poetry if they broke free from internal restraints and, famously, if they’d lower their standards. The elite gatekeepers of verse rarely cottoned to that affront to their elevated-language identity, though they grudgingly accepted the congenial Stafford into their circles.

Stafford built his poetry on the sound of language creeping in from wherever it wanted, often the mundane doings of dailyness, and taking him wherever it took him. He reveled in imagery from the natural world. Streams, rocks, trees, and prairie winds make recurring appearances as touchstones, inspiration, solid and fluid realities that guide our way. Contemplating the influence of those who love or hurt, Stafford offers solace in the stillness and hidden force of nature: “What the river says, that is what I say.”

To read Stafford today is to appreciate the richness and diversity of modern and contemporary poetry.

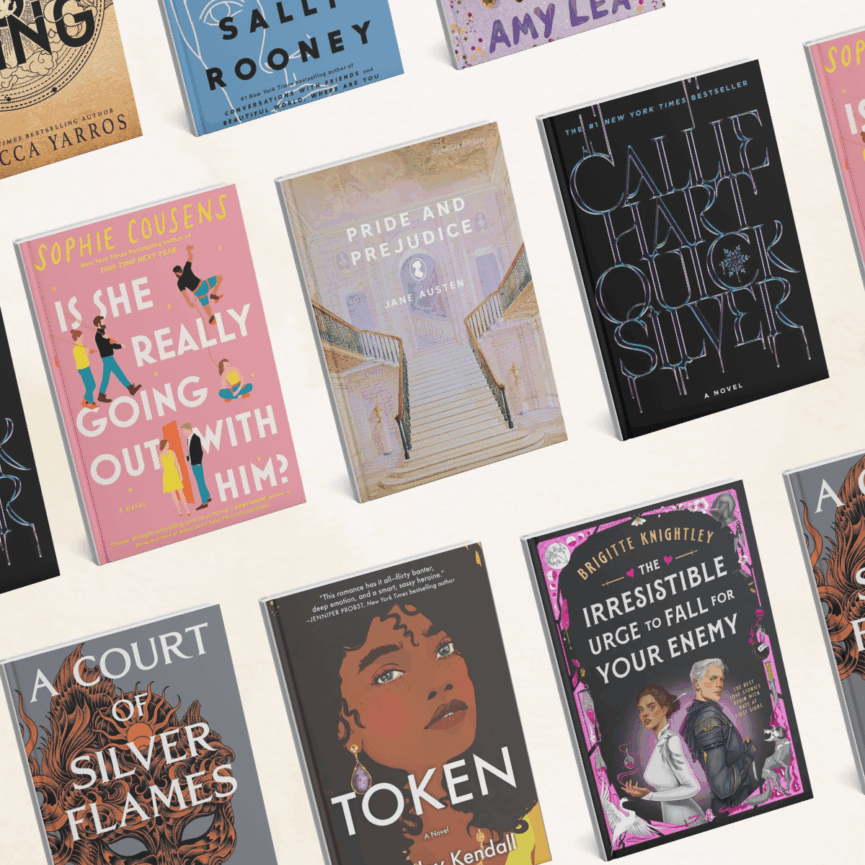

If you’ve forgotten or never knew how appealing and energizing Stafford’s poetry could be, a good collection to have by your easy chair is The Way It Is, published posthumously by Graywolf Press in 1998. Another is Ask Me, a gathering of “100 essential poems,” edited by his son, the poet Kim Stafford, and published by Graywolf in 2014.

As I returned to Stafford’s work more than three years ago, with the thought of writing his biography, two adjacent pages of The Way It Is stopped me in my tracks. I eventually wrote about how the four poems on those pages, very different from one another, seemed to operate as a primer or a workshop on Stafford’s craft and helped to crack open a door that led at least partway to enlightenment. The poems, a total of sixty-one lines, include a riff on the physical experience of Tai Chi and the outer movement of the ocean; a meditation on Thomas Mann’s novel The Magic Mountain; a boyhood memory of a carnival; and, in great contrast to the others, an elegy for his oldest child, Bret. Stafford was deeply shaken by his son’s suicide, on Nov. 7, 1988. This was one of those buffeting winds that arise in our lives and that appear like cosmic messengers in the unpredictable flow of a Stafford verse. It would be a month before he was able to begin to process on paper what he would only refer to in conversation or correspondence as the “jagged event.” The result was the first draft of “A Memorial: Son Bret”: “In the pattern of my life you stand/ where you stood always, in the center/ a hero, a puzzle, a man.”

To read Stafford today is to appreciate the richness and diversity of modern and contemporary poetry and to understand how he managed to make human connections, as if that were the absolute mission of his work. For a reliable witness, I frequently turn to Naomi Shihab Nye, a next-generation poet who remains devoted to Stafford’s work and his legacy. “Stafford,” she has written, “believed in so many potent, magnificent things in his poems, but he never gave false assurance that days or tales would work out perfectly. Rather, he offered the widest, closest, most balanced gaze of any twentieth-century poet. He scanned the horizon and told us the truth.”

Navigating the truths and mysteries of a life is the biographer’s principal task. It’s remarkable to me that thirty years after Stafford’s death we have much yet to learn both about him and from him at the same time.

.jpg)