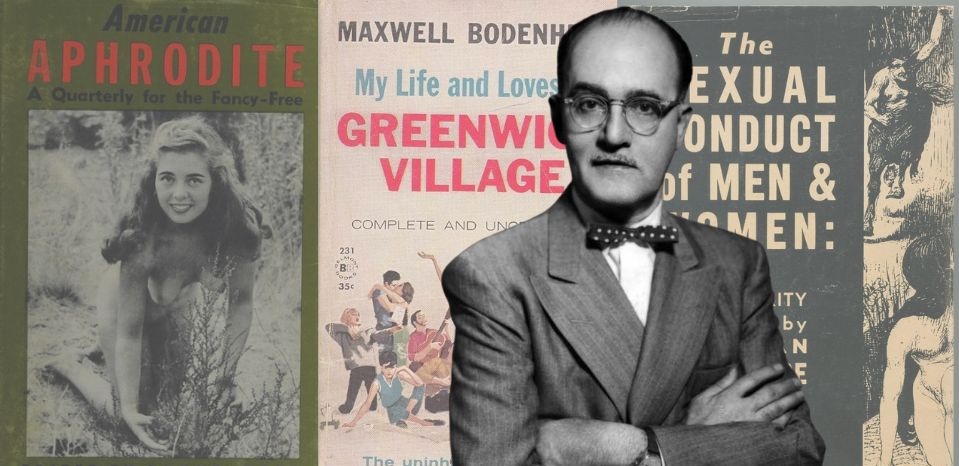

Samuel Roth was the sort of bookseller whose wares came wrapped in brown paper. Titles like Gershon Legman’s The Sexual Conduct of Men and Women, Maxwell Bodenheim’s My Life and Loves in Greenwich Village, and most notoriously his anthologized periodical of high-brow smut, American Aphrodite: A Quarterly for the Fancy Free. Roth—poet, publisher, pornographer—was a creature of mid-century Times Square, a red-hued midnight kingdom of peep shows and “Live Nude Girls,” of Tijuana bibles and X-rated theaters. The glorious and filthy, dingy and beautiful metropolis of brownouts and graffitied subway cars was very much part of the publisher’s legacy.

Article continues below

Galician-born and raised in the Lower East Side world of Yiddish newspapers and theater, this son of Ukrainian Jewish immigrants’ initial forays into the literary world was as an ancillary to the Modernist aesthetic holding sway on either side of the Atlantic. Before he was a notorious bookseller, Roth was author of a pair of experimental epic poems, Europe: A Book for America and Now and Forever, as well as the promising lyric debut First Offering: A Book of Sonnets and Lyrics. “What will you have taken from me/You have not taken yet?” Roth wrote in a 1922 issue of Poetry Magazine, published before his career took a rather different turn.

The line between filth and edification, smut and transcendence, porn and literature, isn’t to be evaluated by judges and censors…but by readers.

Regardless of his own (not insubstantial) writing, his greatest poem was one on which he was at best a cowriter—Roth v. United States, the 1957 Supreme Court case that would begin to redefine “obscenity.” Any great poem—which is to say a true poem—must ultimately be a failure, and in that regard Roth v. the United States was triumphant, for with some irony, the defendant lost the case. The 6-3 decision of the Warren court ruled that obscenity was not protected by the First Amendment and that American Aphrodite (which included the avant-garde memoirist Anais Nin) was most definitely obscene.

Still, the opinion by Justice William J. Brennan Jr. greatly circumscribed obscenity’s definition, so that now material could only be banned if entirely scatological or pornographic. The case was instrumental in the history of American free speech, where even if it hardly abolished censorship, it was first in a line of decisions that would. Conservative pundits blamed those later cases, particularly Miller v. California sixteen years later, for Deep Throat, The Devil in Ms. Jones, and Debbie Does Dallas, but these were also the rulings that made it possible to read unexpurgated editions of D.H. Lawrence’s Sons and Lovers, Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita, and Tropic of Cancer by Henry Miller. The cost of James Joyce’s Ulysses, a book where Molly Bloom’s beautiful soliloquy (“yes I said yes I will Yes”) earned Roth six months in detention in 1929, is Hustler and Penthouse, YouPorn and OnlyFans—not that this can be reduced in such a way, nor need we denigrate the later things in service of the former.

That was much the position of Brennan in his majority opinion for Miller v. California, rethinking his previous perspective and concluding that “no formulation…can adequately distinguish obscene material unprotected by the First Amendment from protected expression.” One person’s canonical literature in the form of Fanny Hill: Or, Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure (John Cleland, 1749) is another’s pornography in the form of Deep Inside Annie Sprinkle (Annie Sprinkle, 1981). Which is to say that the line between filth and edification, smut and transcendence, porn and literature, isn’t to be evaluated by judges and censors, or even critics and scholars, but by readers.

Roth’s own road from the bohemian utopia of the Village to the antinomian excess of Times Square was itself seamless, having arrived in the libertine empire that was 42nd Street through high culture itself. Though his personal motto at the William Marro Imprint was “publish and be damned,” Roth’s reputation was developed through the promotion of erotica excerpted from passages of some of the twentieth century’s most celebrated masterpieces, including Lady Chatterley’s Lover and Ulysses, having been the first in the United States to do so. Ironically, Joyce himself initiated the first real campaign against Roth, as those passages reprinted in the magazine Two Worlds Monthly were pirated, the Irish novelist responsible for a 1927 international protest against the publisher because of his plagiarism. All of which is to say that Roth was an imperfect advocate for free speech, a man paradoxically hard to admire but easy to respect.

A Columbia dropout, Roth’s actual university was Moyamensing Prison where he served two months; his salons conducted at Lewisburg Federal Penitentiary where he served (across two separate sentences in two different cases) a cumulative seven years. Though it is the right-wing who today hypocritically carry the banner of free speech, crowing about “cancel culture” and the “woke mob,” the actual legal threat to free expression comes from where it always has—those same conservatives complaining in the first place (and their fellow travelers, the useful idiots among centrists and moderates who refuse to identify the real danger).

The shrieks of those who claim that we can’t hear them are ironically deafening. Boise State University professor Scott Yenor, upset that many people were also upset at his free speech and responded with their own free speech, casts himself as a martyr at First Things, describing his treatment as “inhumane and corrupting.” Michael Lind at Tablet conspiratorially proffers that there is a cadre of woke infiltrators, “acting with the specific goal of seizing control of institutions,” while at Unherd Jonathan Sumption makes the risible claim that the single greatest threat to free speech are LGBTQ activists, writing that “cancellation of speaking engagements and publication contracts” is de facto authoritarianism.

According to Sumption, and Lind, and Yenor, a zealous (and somehow powerful?) coterie of leftists is singlehandedly abolishing free speech. What all of these public intellectuals, to which could be added figures as varied as John McWhorter, Bill Maher, Paul Berman, and Bari Weiss, conveniently ignore is that free speech’s most powerful and effective enemy remains who it’s always been in this county—the political right. Because public shaming—itself free speech—isn’t prison. Nor is getting cold shouldered in the faculty lounge, receiving negative student evaluations, or being ratioed on social media. Just ask Roth.

Humans are holy and so then must be their speech, where though all of us are free to not listen to it, we’re not privy to silencing it either.

As the defendant in the penultimate Supreme Court case before a right to obscenity would be affirmed, Roth is representative of how the legal system has been used to censor and punish speech which is objectionable to the status quo. The Comstock Act of 1873 banned the mailing of certain works through the U.S. Mail, notably Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass, though it also targeted writings on women’s health, and last year ultra-conservative federal judge Matthew Kacsmaryk invoked that legislation in his argument banning the shipping of medication to terminate pregnancies.

Meanwhile, the capital of Massachusetts, now notoriously liberal, was such a haven for censorship, promulgated by a strange union of Puritanical Brahmans and the Catholic Church, that the phrase “Banned in Boston” remains infamous. Among other works that were not available for sale within Boston were The Sun Also Rises by Ernest Hemingway (banned in 1927), Lady Chatterley’s Lover (banned in 1929), and even Giovanni Boccaccio’s The Decameron (censored way back in 1894)—as well as Whitman, of course (1881). All of this was justified through the Comstock Act, named for Andrew Comstock, postal inspector and president of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice. A fervent Christian fundamentalist who called books “feeders for brothels,” Comstock was responsible for the destruction of an astounding fifteen tons of printed material.

Those crowing about cancel culture may argue that the direction of political censorship has shifted left, but overzealous Twitter warriors aside, the threat remains on the right. The organization PEN America reported that in 2023 there were book bans targeting a total of 1,300 titles at school districts across 33 states, with the American Library Association listing among the most targeted including All Boys Aren’t Blue by George M. Johnson, This Book is Gay by Juno Dawson, and The Bluest Eye by Nobel Prize winner Toni Morrison.

Ultra-reactionary groups like the ironically named Moms for Liberty have targeted books that disagree with any aspect of conservative orthodoxy, especially works that deal with race or gender. Even more shocking—with shades of Roth’s ordeal a half-century after his death—Gender Queer, a Memoir by Maia Kobabe and A Court of Mist and Fury by Sarah J. Maas were put on trial for obscenity in Virginia. We need not fear Stalinism since right now we’re facing Comstockery.

Speech, as Roth understood, is the body’s shout, cry, shriek, whimper, pout, moan, and laugh that can always be answered in kind by another. The only justification for freedom of expression, for free speech, is something intangible and ineffable, a reasoning that’s mysterious if not metaphysical, and that’s that speech—the very breath of the body—is the inviolate expression of the individual human soul. Humans are holy and so then must be their speech, where though all of us are free to not listen to it, we’re not privy to silencing it either.