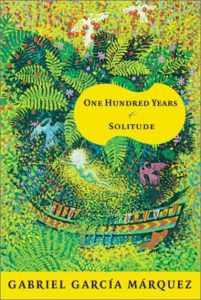

Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice…

Pablo Neruda called it “the greatest revelation in the Spanish language since Don Quixote of Cervantes.” William Kennedy deemed it “the first piece of literature since the Book of Genesis that should be required reading for the entire human race.” Harold Bloom, on the other hand, felt the novel to be “rammed full of life beyond the capacity of any single reader to absorb.”

To celebrate the 56th publication anniversary of Gabriel García Márquez’s multi-generational magical realist opus—the epic tale of seven generations of the Buendía Family in the fictional Columbian town of Macondo—here’s a look back at some of the first English language reviews of One Hundred Years of Solitude.

*

“One has only to read a few pages of Márquez’s novel to understand the response it has occasioned. Immediately, the reader senses in its style a simple audaciousness which alerts him to the premise that he is attending to something more than an ordinary chronicle of fiction, that he is being presented, rather, with a work that presumes nothing, that starts from a beginning both in literary and historical time, as if existence itself had no previous records or memories.

…

“Cien años de soledad may indeed be a depiction of a time and a culture, but Márquez also makes it clear that his tale is more a dream of art than a collection of social and historical truths, and, at the work’s end, when this dream takes on the force of a metaphor for all the cycles of human life that have vanished, one realizes that the excellence of this book lies in its victory over the quaint and anecdotal, in its sustained vision of the vanities and futile passions with which humanity tries to forestall its fate of being, in art and actuality, comically impermanent.

…

“Márquez forces upon us at every page the wonder and extravagance of life, while compassionately mocking its effusions; and when the book ends with its sudden self-knowledge and its intimations of holocaust, we are left with that pleasant exhaustion which only very great novels seem to provide; for they allow us, in a moment of exquisite balance, to hold a vision—to be sure, in some fear, but also with humor—of the beginnings and ends to all the enterprises of living. Márquez, with his tale of Macondo and the Buendías, strikes such a balance and makes us feel as if we had survived his century of articulate dreams only to awaken and discover that they must finally all come true.”

–Jack Richardson, The New York Review of Books, March 26, 1970

“Macondo oozes, reeks and burns even when it is most tantalizing and entertaining. It is a place flooded with lies and liars and yet it spills over with reality. Lovers in this novel can idealize each other into bodiless spirits, howl with pleasure in their hammocks or, as in one case, smear themselves with peach jam and roll naked on the front porch. The hero can lead a Quixotic expedition across the jungle, but although his goal is never reached, the language describing his quest is pungent with life.

…

“It is not easy to describe the techniques and themes of the book without making it sound absurdly complicated, labored and almost impossible to read. In fact, it is none of these things. Though concocted of quirks, ancient mysteries, family secrets and peculiar contradictions, it makes sense and gives pleasure in dozens of immediate ways.

…

“…to isolate details, even good ones, from this novel is to do it particular injustice. Márquez creates a continuum, a web of connections and relationships. However bizarre or grotesque some particulars may be, the larger effect is one of great gusto and good humor and, even more, of sanity and compassion. The author seems to be letting his people half-dream and half-remember their own story and what is best, he is wise enough not to offer excuses for the way they do it. No excuse is really necessary. For Macondo is no never-never land. Its inhabitants do suffer, grow old and die, but in their own way.”

–Robert Kiely, The New York Times, March 8, 1970

“England is now certainly the last remaining civilised country in which the extraordinary zest and originality of contemporary Latin American fiction has not been recognised.

…

“One Hundred Years of Solitude has been written with the recent Latin American literature of fantasy so firmly in mind that on one level it operates as parody of and reflection on what has gone before. Writers like Borges, Fuentes, Rulfo, Cortázar and particularly Carpentier are all obliquely alluded to and self-consciously parodied in the novel.

Far from indulging in portentous literary games, however, García Márquez’s novel aims helpfully to interpret and illuminate what has gone before, offering an explanation and a context to what often seemed purely gratuitous fantasy.

…

“Many of the ingredients of contemporary Latin American fiction are packed into this novel. As in other novels, particularly in Carpentier, a savage nature voraciously devours civilisation if it is riot hectically kept at bay; the cult of male virility is fervently, if periodically and humorously, sustained; and as in many Latin American novels, human events are seen ultimately to unfold not progressively but cyclically.

…

“May it, finally, be hoped that this enthralling, exceedingly comic novel will not encounter the lazy indifference that other Latin American novels have met with in this country.”

–David Gallagher, The Observer, June 28, 1970

“This extraordinary novel obliterates the family tree in a prose jungle of overwhelming magnificence … Above all, García Márquez (via his translator) feeds the mind’s eye non-stop, so much so that you soon begin to feel that never has what we superficially call the surface of life had so many corrugations and configurations, so much bewilderingly impacted detail, or men so many grandiose movements and tics, so many bizarre stances and airs.

…

“Let it be said that, although the man’s sentences are immaculately built, the vision they contain is violent and lurid enough to make the works of two better-known Latin Americans, J. L. Borges and Julio Cortázar, look (respectively) mincing and pretty.

…

“It’s a prose that’s always controlled, but it expresses a vision full of lunges, spurts, mild or maniacal hallucinations, preternatural heavings and bulging gargoyles. Tracing the growth of Macondo, García Márquez is rather like an infatuated god watching a planet seethe and bubble, settle and cool, and then develop forms of life that finally annihilate themselves. The town, of course, is made of prose, as is the ever-encroaching jungle; and, such is the prose’s dense physical immediacy, you have the sense of living along with the Buendías (and the rest), in them, through them, and in spite of them, in all their loves, madnesses and wars, their allegiances, compromises, dreams and deaths.

…

“The verbal Mardi Gras which is his mode of narrating invokes a before and an after (birth and death), which no hyperboles, his or ours, can alter. Like the jungle itself, this novel comes back again and again, fecund, savage and irresistible.”

![Ted Lasso Recap: Season 3, Episode 12 — Series Finale Explained [PHOTOS] Ted Lasso Recap: Season 3, Episode 12 — Series Finale Explained [PHOTOS]](https://tvline.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/ted-lasso-finale.jpg?w=620)

![‘The Orville’ Recap: Season 3 Episode 2 — Claire’s [Spoiler] Visits ‘The Orville’ Recap: Season 3 Episode 2 — Claire’s [Spoiler] Visits](https://tvline.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/orville-3x02-recap.jpg?w=620)