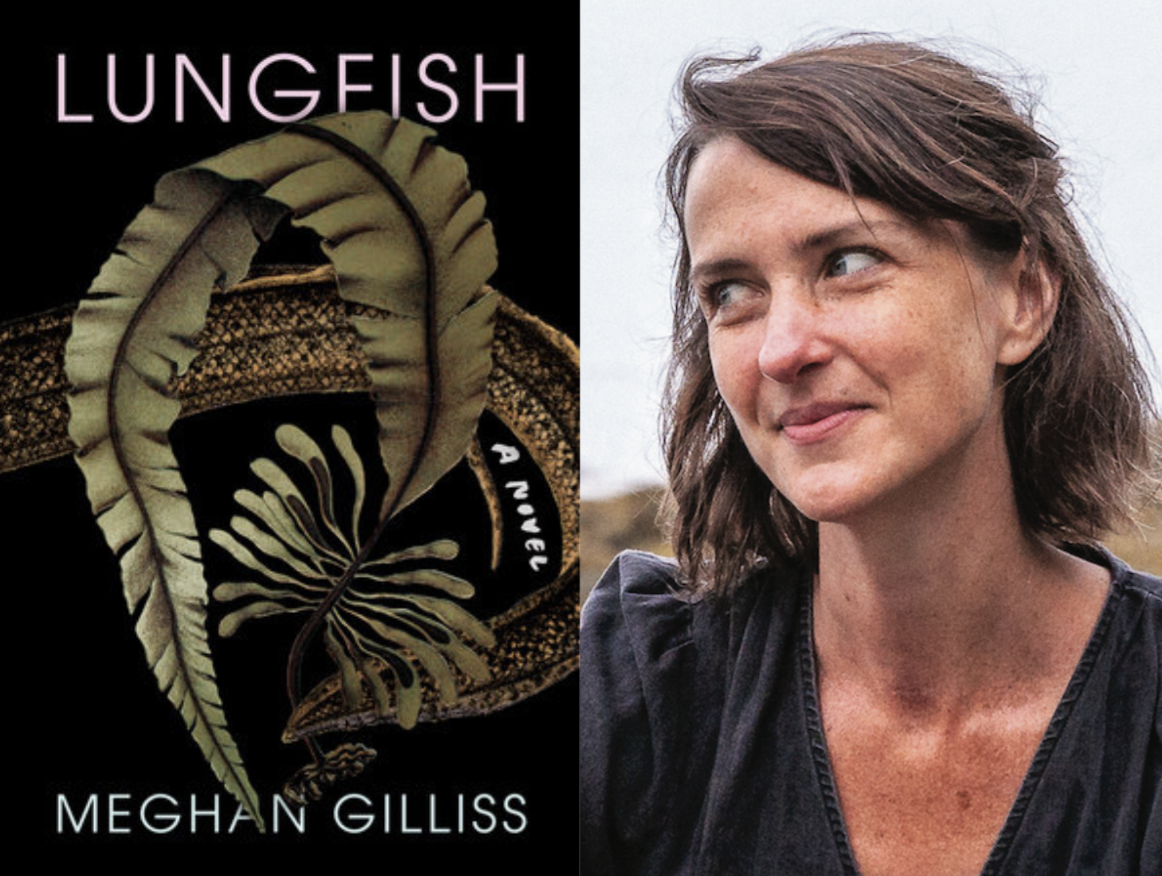

Meghan Gilliss’s debut novel Lungfish tells the story of Tuck, a new mother residing on an uninhabited island off the coast of Maine, with only her child and her detoxing husband for company. As Tuck watches her husband Paul painfully ween himself off the opioid-like drug kratom, she grapples with questions about marriage, motherhood, and addiction. Experimental in form, Lungfish is segmented into page-length chapters resembling prose poems, mirroring Tuck’s own dissociative response to the isolation and scarcity that constrict her life. I spoke with Gilliss via email about catharsis, nature writing, and her personal connection to her protagonist.

Liv Albright: As Tuck finds with her research, kratom is used to help alleviate symptoms of withdrawal from supposedly more harmful opioids, yet her husband, Paul, is addicted to kratom. How did you hear about kratom and why did you choose it for Paul’s drug of choice?

Meghan Gilliss: My relationship to kratom in real life is very similar to Tuck’s relationship to it, and unraveled similarly, in emotional terms. I began this book in 2016, when no one was really talking about the drug. It was a struggle, writing the novel from Tuck’s perspective—giving the reader enough information about what was going on to feel grounded, while maintaining the sense of her own disorientation and lack of solid information. There were points during the revision process when I thought that it might make more sense to substitute kratom with a substance more readers could easily latch onto, but in the end that extra layer of Tuck’s isolation and confusion felt worth keeping; our problems are never as simple as other people’s problems, and they are always entangled with other unique problems, which means that solutions have to be completely custom-built and don’t come easily. I chose to designate kratom as the drug in the novel because I believed it might keep readers more alert than they’d be if the characters were under the sway of a substance people are more familiar with. It was also cathartic—a kind of revenge against a part of the industry that in my own experience had knowingly cultivated and profited from the addiction of others.

LA: Themes of addiction are balanced with nature in Lungfish. Nature is given as much importance, if not more importance, than humans in the novel. Tuck sometimes senses her family members in the earth, and at times plants and trees are characterized as living, breathing beings. What is your relationship with nature and why does it manifest so strongly in your work?

MG: I think that there are people writers and there are nature writers. And I think which one you are might come down to which community—of people or of nature—gives you that sense of being at ease, of being in your own skin. I think I’m just the second kind—writers who have always known we don’t think or talk fast enough to live in a place like New York, as good as it might be for a writing career. The ability to reflect on the natural world in writing is a huge opportunity, too, in terms of developing selfhood. But also, in this novel, Tuck is grasping at things—whatever is actually there in front of her—to help her make sense of her situation. She happens to be isolated within a very natural setting, so it makes sense that she tries to draw some meaning from it, or even just understand it.

LA: In your short story “Old Money,” published in Salamander, the narrator’s ancestors have built a house on an island, which is central to the story. This is very similar to Lungfish, where the narrator is squatting in her deceased grandmother’s island home. Did “Old Money” at all inspire Lungfish?

MG: Lungfish probably did borrow some themes from “Old Money,” but “Old Money” first borrowed those themes from my life. We have a piece of property like this in my family—a steadily shrinking piece of the land that generations of my ancestors have spent time on, though I do worry about how they came to have it. It’s a complicated place—my deepest home, but at the same time a place that can’t be experienced without the awareness of the huge unearned privilege of having access to it, coupled with the deep and real fear of losing it. Peace is experienced alongside unrest.

LA: In “Old Money” and several other of your short stories, including “A Bush in Harbor View,” poverty is a central theme. This is also the case in Lungfish, where the family gets evicted after Paul, the husband, loses his job. What draws you to writing about the experience of poverty?

MG: I grew up in a family that had been declining economically for generations. Culturally, I was taught to have the concerns of a wealthier class. But practically, I had the concerns of someone living paycheck to paycheck for my entire adult life. I remember being a kid and asking my dad how much money he earned, and he wouldn’t tell me, basically saying it was impolite to talk about these things. I was just trying to understand how much you needed to earn to be okay—we were getting by, but I grew up attending private schools and so ran with a much wealthier crowd, never inviting anyone over to my house. At a certain point in life, it just started feeling better to be open about money, and the lack of it, and the interesting situations the lack of it causes. While I hate the fact that so much of America lives in poverty now, I’m at least grateful for the fact that people talk about their poverty and don’t take such great pains to hide it.

LA: The novel also plays with this idea of women’s bodies being inadequate. Tuck feels like she’s not supposed to feel hunger, and her trouble starting the boat leaves her feeling that “female bodies were just missing something. Some muscle in the shoulder that made the necessary motion possible.” Yet Tuck is an active force, collecting food and caring for her daughter, while Paul is incapacitated in a detox state. What do you make of this gender dynamic? Can you talk more about Paul and his motivations?

MG: I think Tuck is a person for whom passivity had no noticeable consequences until she became a parent. I think that like other heroines—like the narrators in Joan Didion’s Play It as It Lays, Ann Beattie’s Walks with Men, and Mary Robison’s Why Did I Ever—she is wired as a receiver, a sort of collector and compiler, but less so for action or even necessarily synthesis. But sometimes, even for these people, action is eventually demanded. I think people across the gender spectrum are wired this way, though of course it’s most cultivated and appreciated in women. Certainly, when it comes to Tuck’s internalization of the idea that she should not feel her own hunger, you realize she’s been damaged by societal messaging. And as for Paul, I think he loves his family and is driven away from them by shame as much as by a protective need for secrecy. I think his own deep need for something in order to feel okay—in his case, drugs—overrules all the choices he’d rather make. His brain was hijacked, as addicts’ brains are. Unfortunately, it’s pretty simple and really not the least bit moral.

LA: Tuck spends much of the novel questioning her faith. Meanwhile, you thread religious imagery throughout the narrative. Can you explain your approach to writing about faith and religion?

MG: Addiction forces you to face your own ideas about God and all that. Parenthood also makes you feel inclined to revisit your beliefs; you begin to understand, if you didn’t already, why human beings rely on belief systems. For Tuck, who is surrounded by the evidence of her grandmother’s faith in the Christian God, religion and faith exist as alternatives and experiences, potentialities—and even, I think, they represent feelings of being left out, of some understanding that access will be granted only in exchange for self-obliteration. Is it worth it? Mostly, Tuck has to choose, day in and day out, what to believe about her situation, and then has to move forward with that. It takes her a while to learn she has to do that even if it means potentially being wrong.