How should a society decide who gets to be a writer?

In the present-day U.S., the answer is simple: Submittable.com. While the specific target of the submission may differ—literary journals, MFA programs, agents, or writing contests—the experience of trying to make it as a brand-new writer has broadly unified around the singular method of submitting semi-anonymously online, tossing one’s work into the ocean like a letter-in-a-bottle and praying that someone reads all the way to the bottom on the other side.

In many ways, this is just an extension of earlier procedures that existed throughout the twentieth century, when authors would submit manuscripts to editors or publishing houses directly, either in person or by mail. But like most things touched by the Internet’s infinite monkey’s paw, there is a point at which a difference in degree becomes a difference in kind. There’s a phase change that occurs in your reading when you are tasked to read not two manuscripts in a day, but 200; when every manuscript that you don’t read that day becomes piled on top of the next day’s 200; when that 200 accumulates finally into 2,000, 4,000, 14,000.

At a certain point, when there are so many people crowded in the same room to see the Mona Lisa, no one really gets to see the art at all.

At the Iowa Writers’ Workshop in the 1980s, director Frank Conroy used a shorthand to classify genres of writing based on the percentage of imaginative involvement required from the reader versus the percentage made explicit on the page. Pulp fiction, he estimated, requires only 20% from the reader to construct the experience of the book, while the ideal literary fiction requires around 50% from the reader to bring the story to life in their mind, and “difficult fiction” requires up to 80% of generous imagining on the reader’s part. Stories that require a certain quality of attentive engagement to come alive in the reader’s mind aren’t just misunderstood when a reader skims through them—they are not the same story at all. The living story exists between, and without enough attention, it cannot become.

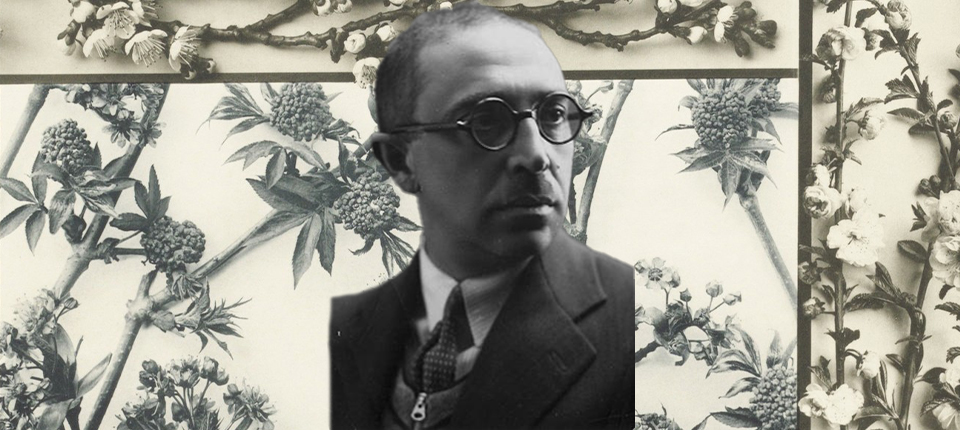

Perhaps it’s no surprise, then, that certain styles of fiction have long had to rely on nepotism (or “connections”) to make their way into the world. You can’t throw a stone through literary history without bouncing off of a journal of friends publishing their friends’ writing. Proust was rejected from every publisher he contacted until his well-resourced friend Rene Blum personally presented the novel to Bernard Grasset, who still only accepted the book for publication on famously harsh “I’m doing you a big fucking favor here, buddy” terms. Virginia and Leonard Woolf’s Hogarth Press more or less exclusively published their friends—and rejected Ulysses by James Joyce in keeping with that tradition. (That particular manuscript would only later be published by Joyce’s personal friend Sylvia Beach.)

This literary nepotism, while just as noxious here as everywhere, historically served a crucial function. I thank God every morning that I exist in the timeline where Proust’s friend Rene was able to muscle In Search of Lost Time into being and not the parallel universe where I was never able to exist in the quiet of Marcel’s mind. Then as now, there are large categories of complex art that simply can’t make it out of the infinite slush pile, and in the past, nepotism was the dirty trick that some artists used to escape it anyhow.

This literary nepotism, while just as noxious here as everywhere, historically served a crucial function. I thank God every morning that I exist in the timeline where Proust’s friend Rene was able to muscle In Search of Lost Time into being and not the parallel universe where I was never able to exist in the quiet of Marcel’s mind. Then as now, there are large categories of complex art that simply can’t make it out of the infinite slush pile, and in the past, nepotism was the dirty trick that some artists used to escape it anyhow.

Now fast forward back to the present, when friendship is dead and there are only five large publishers that dominate every bookstore, agents mediate access to editors and MFA programs mediate access to agents, and everyone, everywhere, is getting hundreds of submissions every hour that their online submission portal is open. Every step of the process is now a slush, far more flooded than ever before, and the only ways to escape are through more slush—while the new MFA credentialism pretends to help you at some of the later steps, that’s only if you’re in the top 1% of applications for that MFA. Put in reverse, your work has to seem remarkable to at least one bleary-eyed reader tasked with sorting through dozens, if not hundreds, of other packets. There is no Rene anymore. If the escape hatch that Proust squeezed through still exists in today’s publishing ecosystem, it’s almost certainly too small for a thousand-page meditation on the mnemonic properties of madeleines. The critic Parul Sehgal has lamented that oversimplified tropes and forms have come to dominate contemporary prose and poetry, and while it’s easy to agree, it’s also easy to see why: How are authors supposed to get out of the slush pile, otherwise?

Not that nepotism is at all defensible. It privileges the well-connected at the expense of everyone else. But our increasingly-inescapable alternative—the slush pile—privileges the simple at the expense of the complex. Meanwhile, the power of individual editors has declined while the volume of submissions only grows ever higher, the concentration of the publishing industry continues to gather more applications into fewer portals, and the culture marches on.

So—how should a society decide who gets to be a writer?

At root, the difficulty is that art, and especially complex art, fundamentally resists large-scale comparative evaluation. The ideal connection to a piece of art or writing requires a generosity of focus and a personal availability to the work that one cannot reproduce, over and over, for all the fourteen thousand applicants to a single slot. You can only patiently try to figure out how so many poems want to be read before you have to stand up and get a glass of water. In the end, it’s often just easier to prefer the poems that you already knew how to read beforehand.

The dynamic is analogous to the effect of Tinder on dating. While it’s evident that the old system of “We fell in love at Harvard because we were both at Harvard—and also because we’re soulmates” was frequently execrable and exclusive, it’s equally evident that the inundation and onslaught of everyone-gets-a-shot dating apps don’t actually give everyone a shot, either. The biases are just different. And, more to the point, it often doesn’t help at all with falling in love.

Ironically or not, it’s the acting world that offers the blueprint of a better solution. For those who aren’t already born to famous entertainers, one of the tried-and-true pathways to break into acting is through the system of locally-based evaluators of talent known as regional theaters. These theaters are generally wonderful and, along with being phenomenal venues in their own right, effectively serve as “farm teams” for unagented actors looking to get representation before migrating to bigger markets. In part because auditions do still require physical presence, such theaters sidestep the issue of large-scale evaluation by shrinking the scale, but in a much more arbitrary manner than nepotistic methods: they only consider artists who live nearby. Without nearly as much bias, they slim down the pool.

“The importance of connections” persists in all areas of art because it serves—poorly, and unequally—a function. Some of the best categories of art just won’t make it without a system of favors to compel gatekeepers to look closely, and not with the skimming-gaze of a slush reader. We’ll never be entirely rid of the deadweight curse of nepotism until we replace it with something that serves that same function at least as well.

But at root, this shouldn’t really be that hard. We just need more equitable ways of keeping the denominator small. Imagine a world of county-specific MFA programs where only residents of that county can apply. A world of powerful regional writing journals, each nurturing their own local scene, and from which prestigious national outlets exclusively accepted submissions. Slush-style approaches to evaluation have long existed, as have ways of getting attention to your work through networking and connections. But the balance has tipped hard toward unprecedentedly high slush piles in recent decades, without any real reckoning with the drawbacks of this approach. The criticisms of modern stylistic trends go by many names—“MFA fiction,” “trauma plots,” etc—but they often stop short of offering a real template for alternatives to succeed. To find and elevate brilliant new art that breaks the mold, we first need to create paths for such work to reach the surface and be seen.