On the Origin of An Ending

An End by Claire Kohda

The sun doesn’t reach the lowest part of our valley for six months each year. It is the position of the mountains. They are very tall on all sides, and with their height they manage to keep daylight from us, until summer comes. I have my favorite. He is a gray mountain—not the tallest but the baldest. For the sake of this story, we’ll call him Bald. He is hunched and it is easy to imagine, inside, a huge curving spine. Bald was the one who told me, in the midst of the long night: An end is coming.

For who? I asked, and I waited, but there was no answer. Do you know?

No. Mountains are not talkative. When they do speak, it sometimes takes days. Vowels are drawn out as long rumbles, but it is hard-stop consonants that delay their speech most significantly. They have to be timed with other bangs and crashes in the world so that humans don’t look at their seismographs and worry an eruption or earthquake is underfoot. This time, though, Bald spoke quickly; and as far as Tokyo on the other side of the world, the ‘d’ of ‘end’ was picked up by humans who hurriedly made phone-calls and listened for seismic activity with new intensity. None came though; that was the end of Bald’s prophecy.

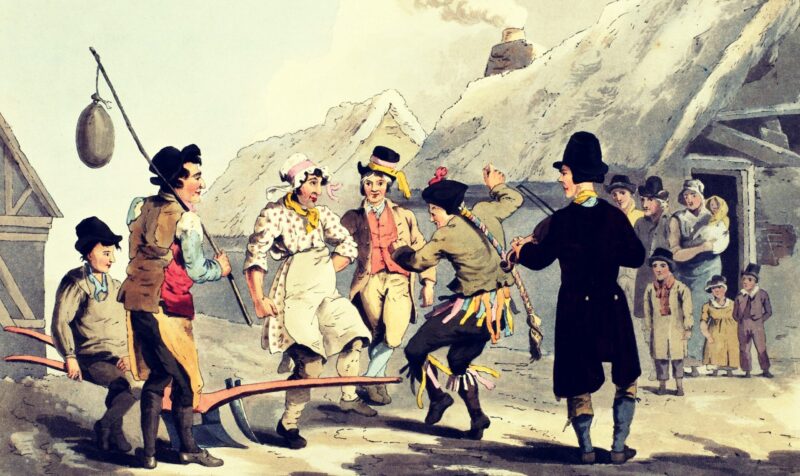

Well, a year passed, and another, then a decade, and a half century. Many other things that had heard Bald’s warning died. Only a few of us remembered. And then, at the end of 1999, finally, an end did come. It arrived in the valley via a route travelled by hunters for centuries. It is an old path, and it wriggles around a mountain next to Bald, who himself is too steep to allow a way for humans. Every day that the sun doesn’t reach the valley floor, it does reach the path up there, and so there is a spot on it where humans for centuries have stopped during winter to skin their kills, or behead, or to have lunch and quench their thirst, before their descent into the town on the other side. Snow melts there quickly, while down here we keep winter for a long time. At the deepest part of our valley, very near to where I live, is winter’s last refuge, and so we call it that: Winters’ Refuge. The cold is welcome here long after it is not welcome anywhere else.

The end came down the hunters’ path, and made across the feet of Bald and Bald’s neighbors, through the woods, right into Winters’ Refuge, where it set up camp right beside one of my banks. Hello, I said. I heard the others around me hold their breath. To most folk down here, ends aren’t to be spoken to. It is better to ignore ends, in case they go off their course and decide to follow after you instead. But I’ve never heard of that actually happening. An end’s course is decided years, if not decades, sometimes centuries before it arrives. Hello, I said again. The end lifted up its head and seemed to hear me, but then returned to what it was doing, which was digging.

What do you think it’s doing? I asked Bald. Sometimes, I spoke to him, even though I knew I wouldn’t get a reply. His wrinkled, grey face was sometimes enough. As if a mirror, I’d pose a question to it, and then in the echo of my voice that came back to me, I occasionally heard an answer. Not this time, however.

There are hoots and chirrups, squeaks, scurries, scufflings and occasional howls in the valley at night. Things that are awake at night are good at hiding in the shadows, so you hear them before you see them if you ever do. The end, though, didn’t hide. The end did not sleep either. Stooped at the base of a tree in Winter’s Refuge, the end had dug through a thick layer of snow and now dug the earth underneath. The rhythm of the end’s digging was regular and unrelenting. Otherwise, it was a quieter night than usual in the valley; owls held their hoots, and wolves their howls, while all around could be heard the scuff-scuff-scuff of the end’s hands pulling up the earth. Mothers and fathers—bats, birds, goats, frogs, snails—they all said to their little ones: Be as quiet as you can, an end is here tonight.

In the morning, the end was still digging. Only, now, it worked slowly. It had reached the roots of the tree it was digging beneath and picked at the earth between each one. Like a seamstress unpicking embroidery, the end seemed to be unpicking the tree from the earth. Who are you here for? I asked, trying my luck again. Shhh, said the wind, and D-d-don’t, stammered a stone. But the end remained silent. Are you digging a grave? I asked. Which one of us is it for? It was no use. The shadowy body of an end contains muteness, not words; silence, not sounds; a stop, not a start.

We all got used to the end’s presence after a while. Day after day, the end quietly sat unpicking the tree, occasionally digging further down to get to the deeper roots, but most of the time sitting on the heap of earth and snow it had made, quietly getting on with its work. Gradually, hoots, howls, scurryings and squeaks returned to the nights, and in the days, the bleats of goats and bird song bounced off the mountains again. On Bald’s face, several goats balanced on craggy platforms that to any other animal were mere notches in the rock, tempting death—a sure sign the end’s presence was forgotten since, the story goes, Death and ends are good friends and if an end is near, then so is Death. I got used to the end’s presence too; I continued with my day-to-day existence, quenching and washing and running, as I had for hundreds of thousands of years and would do for hundreds of thousands more. But, sometimes, I looked at Bald’s face, around the time when the sky started to darken and, in the shadows cast on it, I thought I saw an expression of foreboding.

Soon, it was Christmas time, and Winters’ Refuge was deep with snow. Each day, the end had to dig through new snow to reach the tree roots it had been picking through the day before. The pace of its work changed. Often it checked roots and found they’d already been unpicked, the work already done; I sensed that the end’s job was almost over. Many things in the valley were at the deepest and stillest parts of their hibernation. I was feeling the chill but was still awake, as was Bald, and I decided to travel through the valley on my current and leave the end to its unpicking, and see if there was anything in the valley that was amiss. I didn’t travel long before I reached a small, plump goat, grazing under a tree on a frosty patch of grass.

She was different from the other goats in the valley and in the mountains, on account of her round barrel-shaped belly, and her little stout legs. I knew her type; this sort of goat’s long C-shaped horns had been carried out of the valley for centuries by hunters. The silhouettes of humans using the hunters’ path often were pronged with those horns, sometimes just a pair sticking up like a fork, other times two pairs, three pairs, making the hunting party look very prickly from a distance. However, even among her kind, this goat was different. Her horns were tiny and rose just slightly out of her head. Her hooves that were supposed to be well-adapted to climbing on mountain faces like Bald’s were pinched into little pouting shapes that she tottered on unsteadily. Hello, I said.

The goat, like the end, didn’t answer me.

Hello, I said again. And she turned to face me, chewing absentmindedly, and then turned back to her tree. Her eyes were just like the eyes of other goats—pupils slitted rather than round—but slightly bossed: inward looking, like she was gazing not at what was in front of her but at her nose instead.

Can you hear me? I asked. Do you understand me? I asked even though I knew that everything in the valley could understand me. When they were thirsty, I called them; when they were hungry for fish, I told them where along my body to go. But I felt like this goat was different, like she flew against what I knew. She seemed to not understand my words.

Are you alone? I asked, thinking she might be a lost kid. Where are your parents? And the barrel-bellied goat turned to me again and gave me a blank look. That look, it scared me. Never had I had an animal look through me as she did, with no purpose, or meaning. I gave up on questioning her then. And the goat turned back around to her patch of grass. But the grass was now gone and instead of eating she lowered her head and seemed to suck on the snow. As she did, I spotted a collar around her neck. A dark collar with a box affixed, made from one of the materials of humans. Plastic, it was called. Inside, electricity. I wondered if it was this box that was making her mute and strange.

Never had I had an animal look through me as she did, with no purpose, or meaning.

I stayed with the odd goat for that day; then travelled back to my favourite spot, where Bald was in full view. I said to him, Something’s not right. I found a young goat, but she didn’t seem like a goat anymore. The shadows were on Bald’s face again, and he frowned in my direction. She seemed lost in her own body, I said.

After that, I spent a little while each day travelling this way and that along my course, searching the valley for other goats of her kind. If I found her herd, I’d be able to lead them to the barrel-bellied goat, and they’d remove her strange collar and, I imagined, she’d gain back her comprehension, and lose her blank expression. Usually, they are easy to spot. Their long horns break up the straight lines of trees, and carve curves into snowy scenes. But, I went all the way through the valley where I flowed, through all of the forests, and their clearings, and couldn’t find a single one. I only found the other type of goat that lived in these areas, a larger species, with less impressive horns, and they just shrugged and sipped at me, and then moved away, like they didn’t want to be involved.

When I returned to my spot after searching each day, the barrel-bellied goat was often there, grazing on the tufts of grass the end had dug up with the snow and earth. They didn’t pay much attention to each other. Only, sometimes, late at night, I’d notice the goat settle down to sleep close to the edge of the hole the end had dug, and the end would pause its digging, and reach out with a hand, and seem to almost stroke the goat’s body. But at the last minute, it would pull back and turn away from the goat, and keep on its task.

It was the beginning of the new year, and the goat was grazing, and the end was digging, and I decided I would go up into the mountains, right up to my spring. I don’t go to my beginning often. A river gets used to its power; but when we return to our beginnings, our voices get quieter, and our influence on the earth weaker. However, this was the only place I hadn’t looked. I whispered to the goat, hold on, even though I knew she wouldn’t understand, and left her in the care of the end, happily munching beside it. I made my way up-stream, against my current, while Bald watched. As I went, the stones in my water became bigger with sharper edges, and I became thinner and softer. Plants towered over me, and either side, my banks squeezed me in, until I had no banks, but just rocks that I hurriedly passed over. At the top, my voice reduced to a bubbling babbling, I whispered to all the things that lived their lives there who all had strong and jagged voices, and to the wind that made harsh, knife-cutting sounds over the bare mountain-top, asking if any had seen the goat’s kin. I think an end is here for it, I said weakly. A huge, jagged rock of granite with a face with many sharp angles said, Yes. A while ago. We saw one born.

Since then? I asked.

None.

I left quickly. I descended back into the valley, feeling with relief my power return to me, and the stones respond again to my will, their edges dulled. My voice restored to its usual volume, I returned to my spot opposite Bald, where the end carefully unpicked a tiny feather-like tip of a root, and the goat licked the snow. I recognised the goat, now, as alone. The last of her kind. An “endling”—a fitting name, for with no herd, no parents, no one like her left in the world, she could answer only to an end, like a gosling to a goose, a nurseling to its mother, a foundling to its finder.

Night came, and the end continued with its work, and the goat settled down to sleep next to it, and I decided to sing to it. I chose the song I sung to living things when they were thirsty. It was a river song that saves lives; the words draw those that still have life in them to me, so they can take water and save themselves. The goat fell asleep.

Some humans have been known to feed ends. They leave offerings out for them, in the form of skins and antlers, or plants brought from far off lands, and fish from far off oceans. In the valley, we have heard of ends travelling to remote islands on the wind with mosquitoes brought by humans – five, six, even ten, twenty ends, all at once, and half the birds of those islands, gone in an instant. In other places, ends have been left kindling and dry land by humans, with which to start fires with, and so they’ve burned species out of existence that way. Here, we didn’t notice that humans had been leaving bullet casings all over the valley floor and along the hunters’ path for centuries, as offerings to the end that came for this goat. We couldn’t have done anything even if we had known, though. Perhaps I could have lured a couple of the hunters to my edge. Perhaps I could have drowned them so fewer offerings were made, but more hunters would have come, and the end would have followed.

In the morning, we all gathered around it. It was fine work. The tree had been completely unpicked from the earth so that when it fell, it was as if it had never grown there. It left no roots in the ground, not even a tiny fibrous root-end. The tree had been wholly uprooted, and the earth behind it sealed with no memory, even, of the tree’s existence. And, beneath the now-dead, now-removed tree was the goat and the end, now knotted, tied, pinned down together, under the tree’s thick trunk.

A smooth, round stone in my current said, There’s a boulder who remembers the little goat’s birth. Stones talk to stones. They knock into each other and pass stories between them; though sometimes the stories change along the way.

There is? I said.

Yes, near your spring, it said, and I remembered the jagged granite boulder I’d met at my beginning. The mother, though, was mute and stunted. She couldn’t name the child, except with a purring noise deep in her throat. No one can say the name now because none of their kind exists.

We watched, quietly. Nothing happened for us to see. The nameless goat was dead, the end with it; the tree was down; the earth forgot.

“Fuck,” said the human. “It’s Celia.”

“No,” said the other one. She crouched down and momentarily hid her face in her hands.

“She’s dead,” said the first human, a man wearing glasses. The second one, still crouched down, shook her head. She rubbed her eyebrows. Closed her eyes. When she opened them, I sensed she was seeing the world differently, newly. A third human arrived; this one was older with a beard. He covered his mouth and stopped in his tracks. “Oh, Celia,” he said, like the goat was a friend. Then he lowered his hand from his face and stepped forwards.

A few of us, we whispered some words of parting into the moment of silence that followed, during which the humans took photos, and solemnly lifted the tree and removed the end-goat’s body from under the trunk. With bloodied hands, the woman fiddled with the goat’s collar, found the box of electricity attached to it, and pressed a button to turn it off. They turned off the tracker that was connected to it, and that had led them here, too. They had hoped that the collar was broken, not that the goat was dead; this much we learned from the little conversation they had. The humans all shook from the cold, or from being in the presence of an end, and they carried the end-goat away. And there was nothing after that. Just the tree was left. Snow fell and soon covered it.

The first month of the new millennium passed. We held onto winter for as long as the sun stayed behind Bald and the other mountains, as usual. Gradually, though, winter left too. My coldest parts defrosted, and hibernating animals woke up, thin, pale and disorientated, and worms and bugs started to move under the earth again. The snow on the end-goat’s tree melted away, too. But, by now, most had forgotten what had happened there, and the barrel-bellied goat the end had come for. It wasn’t surprising, how quickly she was forgotten. Alive, she had been strange and didn’t seem to have a place here anymore; she’d forgotten the way of her own kind, had no herd to herd with, had no mate to mate with; her hooves had grown inward, her horns had remained hidden inside her head, her legs had stayed short and stumpy. She had made no sense here, and it is better to forget things that make no sense. But I remembered her, and Bald remembered her too. Every once in a while, we paid our respects at the tree that the end had unpicked. In my watery voice and Bald’s gentle, low rumbling of a voice, we said out loud not her name, because we did not know it—we knew only the name humans had given her—but that simply a goat had once lived here and that her and her kind were now gone, unpicked from the valley with no trace left.

When there were tiny changes in the tree that had fallen, Bald and I were first to notice. First, there was just a hint of green along one of the branches; then the green spread, and small leaves started to grow, then a flower bud. Despite being completely unrooted from the ground, life was returning to the tree. Bald said, Something’s changed.

And Bald was right. Mountains, so old, large, connected to so much, are rarely wrong. Something had changed. The flower on the disconnected tree’s branch opened. And, at the same time, elsewhere in the valley, very tiny things reordered themselves. This isn’t my egg, said the black woodpecker who lived in the hollow of an old tree near my first bend. She was looking at her nest of eight eggs; one was smaller than the rest. It’s not mine, she said, when the others asked, Whose is it then?

Mountains, so old, large, connected to so much, are rarely wrong.

How many eggs did you lay?

Eight.

How many are there?

Eight. But this one isn’t mine, she said. Eventually it seemed like she was convinced, or mostly convinced, at least. No one had swapped her egg out for another; no one else had visited her nest. But, that night, she kicked the smaller egg out, and it cracked on the floor at the foot of the tree. Along my course, I heard of other, similar changes: an owl egg was changed, too, becoming more speckled than its parents remembered; a frog’s eggs all failed to hatch and rotted amongst the vegetation in my waters, while another frog’s eggs hatched into not tadpoles but mosquitoes. It was as if something in the valley was playing with the beginnings of things. Seeds transformed in the earth: a beech seed grew into a fir tree, and a maple seed into an oak. Then, under the end-goat’s fallen tree, where now a few small flowers grew, a darkness appeared on the earth, like a shadow but without a body to cast it. From that darkness, a hunched bundle emerged; it rose and straightened, becoming a figure. It was an end. Another end, in the same spot the end-goat had died.

What’s happening? I asked Bald. The end now had crouched down, and had started unpicking its feet from the forest floor, in exactly the spot where the end-goat had been pinned down by the tree. Is it the same end as before? Why has it come back? I said.

But Bald was silent. Mountains, if they know the answer to a question, might speak. But if they don’t know, they won’t waste their energy saying that. Bald was expressionless. The sun was high; its light made his face look smooth and empty.

The end got up, and it started making its way across the forest floor, away from me. It was walking slowly, but with purpose, as ends do. But this end, if it was the goat’s end, had already done its duty; it had fulfilled its purpose. Like the eggs and seeds in the valley, something about it was amiss. So, I travelled up my current, meandering this way and that, trying my best to follow the end and… What was I trying to do? Stop it? Drown it? I wasn’t sure. But either way, soon it was on the hunters’ path, stepping slowly up the side of the mountain, and I was unable to follow.

So, I did something I’ve never done. I climbed up the mountain up towards my beginning again, all the while keeping an eye on the end that still wound steadily along the hunters’ path; and, then, when I felt I was high enough, I broke my bank. I pushed into the earth, despite being so close to my beginning, and therefore very weak – and first I didn’t make much of a dent, but I did at least make a little notch, and then that notch grew, and as more water filled it, the more power I got behind my push, and soon I’d split from myself, and I’d made a narrow stream that trickled over rocks and plants that had never come in contact with river water before. I was travelling down the other side of the mountain, into the next valley, rushing towards a town, where the hunter’s path also led.

I wasn’t confident, dribbling down the mountain; I felt nervous and insubstantial. The stones I passed over remained jagged—they’d only ever been eroded by wind and rain, not river water—and they spoke harshly to me as I passed, telling me I didn’t belong, and that I should go back to where I came from. But if a river learns anything from its early life, it is to follow its convictions; a river makes its own path, after all. Soon, rain came, and it supported me on my journey, making me stronger still. In the pitter-patter of its heavy droplets, the rain said it had been a cloud made above Bald. It would disguise me in the town, it said, so the humans would think I was a long trickling puddle in a storm, rather than a river entering into their sanctuary.

I arrived at the university hospital at the same time as the end. I stayed outside. I pooled in a depression in a path just above a basement window of a laboratory. The end, to my surprise, joined me. It sat down on the path next to me in the rain and, together, we watched a group of humans inside the laboratory who were crowded around some sort of animal that was sound asleep.

The animal was on its side on a table, and tubes came out of its mouth, and a machine was connected to it that beeped. Over its body was a thin blue cloth, with a hole cut like a window over its belly. One of the humans stepped to the side, and I recognized her as the woman who had covered her face at the end-goat’s tree. The two men were there too, and then three others who I’d not seen before who were preparing surgical instruments. All of them wore matching blue gowns, gloves and face masks. Soon, I got a view of the sleeping animal’s head and I saw that it was a goat. Was it the goat? The barrel-bellied end-goat, somehow brought back to life? I glanced up at the end as if it might give me an answer, but it remained still, its gaze fixed. I looked again at the animal and soon saw it had a longer and more elegant face than the end-goat, less stumpy legs, hooves that would make sense on the craggy outcrops of Bald’s face. It was a different type of goat, a kind I’d not seen before. I’d mistaken it as the end-goat because of its belly—it was distended, huge, round. Rounder, even, than the barrel-belly I remembered. But this was a different kind of plumpness. The goat on the table was, I realised, pregnant. A scalpel came down on its stomach.

I had never been so close to an end. As it leaned in to get a better look through the window, I heard a sound coming from deep inside it. I expected maybe a ticking, like the ticking of clocks humans use to tell time. But it was more like the roaring sound inside an empty shell, easily mistaken for the sound of tides turning, but really only the sound of hollowness. I heard at the same time, the tiny fragile heartbeat of the goat’s kid inside her belly through an ultrasound the humans were performing. Those two sounds mingled strangely.

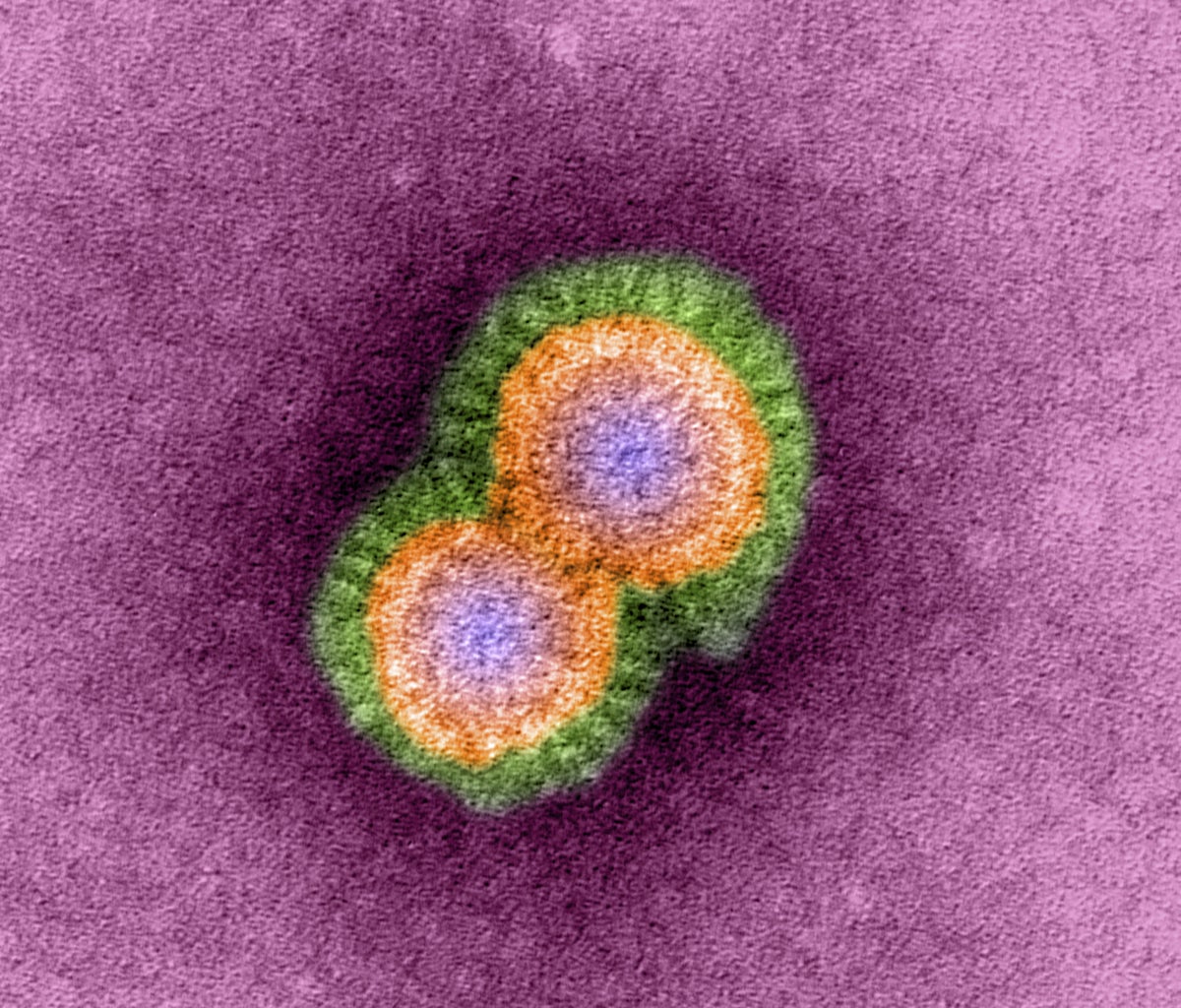

The goat remained asleep while the humans performed the operation. One of them took photos. Soon, the humans had cut through the mother goat, had separated her abdominal muscles, sliced through the wall of the uterus and were lifting a small kid out. It was immediately apparent: this birth was like the frog eggs in the valley that had hatched mosquitoes, and the seeds that grew the wrong trees. In the mother goat was a goat of a different kind. It was the sub-species with the long curling horns, the type that the end-goat had been a stunted version of, the type whose lineage had supposedly ended, whose chapter was closed. An end had already come for this goat. And an end is an end. Once one comes for you, that’s it. You do not come back; you are extinct.

The humans were hurriedly cleaning the kid now. They snipped the umbilical cord, and dipped it in iodine, then stitched up the mother, and gently moved the kid into a clear plastic box and started pressing buttons on various pieces of machinery and plugging the kid in, wiring it up, attaching tubes, taking more photos. A few of the humans in the room high-fived. There was jubilation, mixed in with fear. Fear of losing the kid, perhaps—She’s not out of the woods yet, one of them said; fear of the responsibility of making life where there was supposed to only be barrenness, of turning back extinction, defying an end.

They’ve defied you, I said to the end, and I looked up at it. I didn’t mean for it to sound like a challenge. I was, I thought, on the side of the humans. There was something very brave, though reckless, about what they’d done; it excited me to see an end defied. Yet, at the same time, I felt uncomfortable. An end is an end, I thought to myself. A beginning is a beginning and an end is an end. These are things not to be messed with. An end isn’t a malicious creature. It doesn’t go against nature. It is, in its own way, to be respected, even if humans bring forward its arrival. But perhaps everything that can be saved from an end should be saved, even if it means going back on an end, undoing its doing.

While I’d been mulling all of this over, the end beside me had, without me realizing, scooped a little of my water into its hands. It had then stood up and quietly passed through the wall of the laboratory, into the room with the humans, and stepped up to the kid’s incubator. Now I watched helplessly from outside, as it nudged open the incubator with its head and reached in. Deftly, having descended from a long-line of drowning, suffocation, burning and poisoning, the end placed its hands beside the kid’s head, and gently, almost tenderly, turned the kid’s face using its thumbs into the water it still held in its palms. Nose and mouth in my water, the kid breathed in. The humans noticed something was wrong, and rushed around the incubator, pressing buttons and checking tubes. And the woman I’d recognized from the end tree—she barged in and knocked the end sideways, without realizing, without seeing, and picked up the kid, hoping her warm touch might be able to help it. I’d never seen that: an end knocked to the side, or touched at all. It was only a brief moment. The end, perhaps shocked, stumbled, then regained its footing, and while the kid was in the woman’s arms, and the humans shouted instructions around about oxygen and surgery and this and that, the end quickly passed its hand over the kid’s nose again dropping the last of the water into its airways, and then it was done.

The window, in the commotion, had begun to steam up. The rain had picked up, too. I didn’t have a good view anymore. But I saw the kid, dead now, tucked into a bundle of blankets on the table, near its mother who – like the beech to the oak, the pine to the fir – was a different species, and slept comfortably. The kid had lived for seven minutes. Its kind had been brought back for that time; it had re-existed, and for those seven minutes the order of the world, all the beginnings and the ends had been shaken up and undone, and then, at the end, done up again. The end in the laboratory, its duty done for a second time, joined with its new, tiny endling, as is the way. But as it went, as it collapsed onto the table and into the bundle of blankets to join the little kid, I was sure I saw it tremble as if, now, it and maybe all ends had something to fear. The woman closed the kid’s eyes, and started removing her scrubs.

It was easy to leave the town and climb back up the mountain. The rain had strengthened the narrow stream I’d made into a faster and more powerful torrent. I ignored the harsh words of the rocks on my way up and, back at my beginning, I didn’t mind that my voice was weak; I didn’t feel like talking anyway. I rushed down the other side of the mountain towards the valley, passing offerings made by humans to more ends that would eventually come, scraps of rubbish and left-over camping gear, and I kept going. I passed my favorite spot where I usually lived, opposite Bald and the end-tree, and I went on, on and on, until I was out of the valley through a narrow passage between mountains, and on open, flat land, where my current was extremely powerful and my voice roaring. My banks became steep cliffs that cast me in shadow. Here, it would be impossible for me to carve a new path; here, my path only led to one place. And I kept going until the land drifted further out either side of me, and all I could see was water.

There, I met my end. And I saw that my end wasn’t simply an end but was where I became something else, where I became the sea. I spent a moment there, and then rushed back up against my current back to the valley.

On 6th January 2000, the last Pyrenean ibex (Capra pyrenaica pyrenaica), nicknamed Celia by conservationists, was killed by a falling tree. The sub-species was declared extinct. In 2003, however, 208 clones of Pyrenean ibex embryos were successfully created and transferred into the wombs of Spanish ibex x domestic goat hybrids. One pregnancy reached full term. This clone was born on Wednesday 10th July 2003, making the sub-species ‘de-extinct’. It lived for seven minutes. After that seven minutes, the Pyrenean ibex went extinct for a second time.

![Mandy Patinkin as [Spoiler], What’s Next for Oliver and Josh in Season 2 (Exclusive) Mandy Patinkin as [Spoiler], What’s Next for Oliver and Josh in Season 2 (Exclusive)](https://www.tvinsider.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/brilliant-minds-113-oliver-mandy-patinkin-1014x570.jpg)