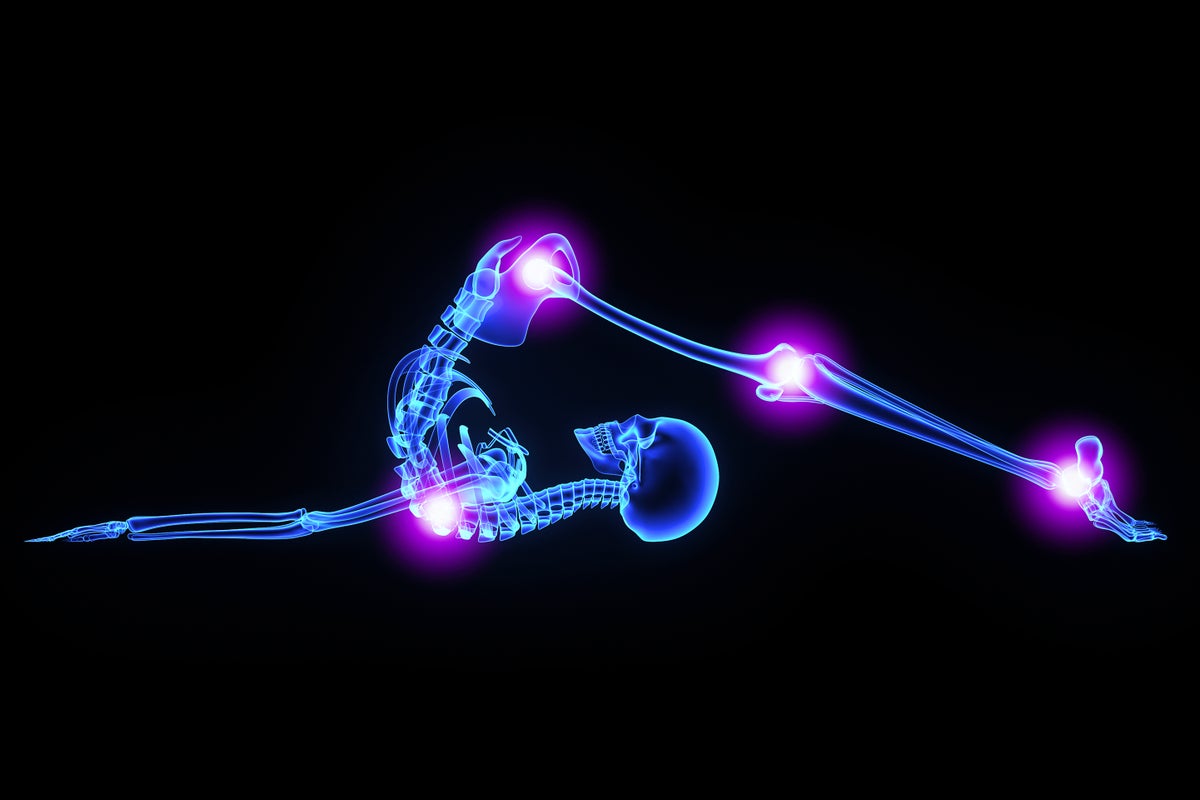

I’m a migraine sufferer. Have been since I was little. Talk about extremes, a physiological trip with precipitous highs and lows. It’s not just the pain, which is considerable, and its dulling aftermath, but the emotions that go with it. There’s the dread you’d expect when you know it’s coming, and then the unfortunate fact that migraine sufferers’ happy-making, pain-fighting neurotransmitter serotonin is taken up too quickly and then runs dry. With the cruel sharp epicenter in the temple or over the eye, and soon the neck and jaw feeling, to me anyway, as if they’re turning to a stone hardened by ache, comes every babbling demon, every judgment of yourself you’ve been negotiating with, every cold-sweat fear for yourself or others. You blame yourself for bringing it on, too—what did I do, eat, or drink, or fail to do, eat, or drink? Did I sleep too long or too little? Did I not take my meds soon enough? Not exercise enough? Is it the weather—that fickle barometric pressure—or perhaps internal weather: Did I let my feelings run too roughshod? And when you emerge, there’s more than relief: a wowing liberation. You can’t believe you’re not hurting like that anymore, no longer distorted physically and emotionally, and the simplest interactions with life, a breeze on your skin, feels a fucking miracle. You swear you won’t let it happen again. Not like that. Generally, you’re wrong.

Joan Didion, in her essay “In Bed,” writes that she often “spent one or two days a week almost unconscious with pain seemed a shameful secret, evidence not merely of some chemical inferiority, but of all my bad attitudes, unpleasant tempers, wrongthink.” She describes pushing through, only to have the body push back with vomiting, tears running from the eye on the right side of her face (a feature of migraine, meaning half-head, in that it tends to strike on one side). Siri Huvstedt has written about her hallucinations before an episode, all too familiar to me: “fogs and gray spots that make it hard to see what’s in front of me, weird holes in my vision, and a sensation that there’s a heavy cloud in my head,” as well as a hallucination unique to her of a “small pink man and his pink ox, perhaps six or seven inches high.” She, like George Eliot, talks about feeling too good before a migraine, having a sudden “amazed connection to the world”—what Eliot described as feeling “dangerously well.”

Joan Didion, in her essay “In Bed,” writes that she often “spent one or two days a week almost unconscious with pain seemed a shameful secret, evidence not merely of some chemical inferiority, but of all my bad attitudes, unpleasant tempers, wrongthink.” She describes pushing through, only to have the body push back with vomiting, tears running from the eye on the right side of her face (a feature of migraine, meaning half-head, in that it tends to strike on one side). Siri Huvstedt has written about her hallucinations before an episode, all too familiar to me: “fogs and gray spots that make it hard to see what’s in front of me, weird holes in my vision, and a sensation that there’s a heavy cloud in my head,” as well as a hallucination unique to her of a “small pink man and his pink ox, perhaps six or seven inches high.” She, like George Eliot, talks about feeling too good before a migraine, having a sudden “amazed connection to the world”—what Eliot described as feeling “dangerously well.”

I collect famous migraine sufferers: In addition to the above writers, there’s Virginia Woolf, Freud, Janet Jackson, Darwin, Hildegard Von Bingen, Lewis Carroll, Serena Williams, Nietzsche. I can trust them; they are a consolation, their lives proof that they coped, overcame, and are a sort of compensation, too, a counter to the wrongthink—I may not have a life like theirs, but I could have a life; the migraines don’t have to stop me, not for long, and indeed some on my list, like Didion and Hustvedt, have credited their migraines with rebooting them or giving them visions from which great work emerges. Take a patient of neurologist, writer, and migraine-sufferer Oliver Sacks: a mathematician who did his most creative thinking after a weekly two-day fall into and out of a bad episode. Sacks is able to stop the severity of the migraines with blood-pressure meds, one of the common go-to prophylactics, but with it went the man’s best work. He opted against the remedy because for him the price of not having pain was simply too high.

I collect famous migraine sufferers: In addition to the above writers, there’s Virginia Woolf, Freud, Janet Jackson, Darwin, Hildegard Von Bingen, Lewis Carroll, Serena Williams, Nietzsche. I can trust them; they are a consolation, their lives proof that they coped, overcame, and are a sort of compensation, too, a counter to the wrongthink—I may not have a life like theirs, but I could have a life; the migraines don’t have to stop me, not for long, and indeed some on my list, like Didion and Hustvedt, have credited their migraines with rebooting them or giving them visions from which great work emerges. Take a patient of neurologist, writer, and migraine-sufferer Oliver Sacks: a mathematician who did his most creative thinking after a weekly two-day fall into and out of a bad episode. Sacks is able to stop the severity of the migraines with blood-pressure meds, one of the common go-to prophylactics, but with it went the man’s best work. He opted against the remedy because for him the price of not having pain was simply too high.

This asks an important question about how we all navigate human life: Asks what will you endure to be you, to best express who you are? What injuries and ailments? What risks and setbacks? What sorrows?

These questions are temptingly well suited to literary fiction and how could I resist writing about terrain, physical and metaphysical, that I know so well? I tried. But this was made impossible by the very mystery of migraine—that we still don’t understand their true mechanism or cause beyond a genetic predisposition and certain triggers—and a walk I took from my apartment to a church that had no congregation anymore, only a preschool in its basement. Recovering from a headache one day years ago, still lobotomized from it and in my case from the triptans taken to move it out quicker than it wanted to go, I longed for company in that basement, comfort in the form of a dixie cup of juice, a graham cracker, and maybe a nap.

But that was not to be, as much as I felt Lewis Carrol-like shape-shifting from the way the contours of the mind and body feel redrawn by migraine, I wouldn’t be right or welcome in that basement. And in truth the only place I have ever gotten real understanding about the headaches that aren’t really headaches but seizures, electrical storms in the brain, were from other migraine sufferers. Especially in the neurologist’s waiting rooms. We whisper to one another about what we’ve tried, what’s worked, what’s not, which doctors on staff here or elsewhere have worked for us, are kind, which have not, are not. We lean in, out, gauge the safe distance between us because we know that the afflicted are sensitive, that parts of the brain that govern the senses are coopted by the mechanism of migraine so that smells, mild to others, are not to us, lights too harsh, and even the sssing edges of whispers can hurt or even the excitement from a treatment working at last. The wild hope. Will it stay? And will insurance cover it? Maybe it’s the Botox injections to numb the nerves riled by the inflammatory peptides released during the storm? The newest CGRP-antagonist concoction that promised to be a cure and isn’t, but it helps; some it helps. The omega-3s, magnesium supplements, the B-vitamin intravenous injection; the herbs, the acupuncture, the biofeedback.

One day I ask a woman I see often in the waiting room, “Better?” She shakes her head. Her migraines are vestibular and chronic. “No,” she says, and ducks her chin to trap whatever feelings are rising in her, and I dare it, I touch her hand, and though I touch it lightly, the implications here are not light—you don’t touch other bodies during plague times, and then many chronic pain sufferers’ skin hurts too; the brain is built to be ever more efficient in its processes, even with the habit of pain, and can begin to claim more territory, more areas given over to sensitivity; the whole body can get into the refining of the act, as mine has in recent years. And hers too. No one wants that. But she doesn’t flinch, she grabs my hand back and holds on.

She is crying a little. Me too, can’t help it. It’s exhausting, avoiding our triggers like addicts trying not to fall off their wagons do, telling on ourselves when we trip up to the doctors who have only so many prescriptions to write and so much empathy. And we are lifted up for a moment, this woman and I, even when she says, “I got too hopeful, you know?” And I think of Didion’s wrongthink, how this woman can’t help but lay the blame at her own door because in this at least there’s the illusion of some control; and I think of the doctor featured in my new novel who’s almost sick with and certainly trapped by his duty to his patients, who’s guilty with this truism, still true in 2023, no matter how many celebrities shill the newest pharmaceutical bids for relief: “I can treat you but I can’t cure you.” Someday, maybe.

I doubt you’ll be surprised that in my novel I write about a headache clinic in the basement of an abandoned church where support groups for sufferers of headache meet. Those who show up swap remedies; they commiserate, quarrel, laugh, cry. These characters are as close as I’ve come to the kind of community where there’s no shame in admitting to pains written into your DNA, pains that some days make you tight with resentment and some days mean you can do nothing but surrender to the pain, as Didion admits to doing in “In Bed.” Better to focus on it than on the emotions that can come and lie and accuse. I ice the head, the neck. I breathe in, out, even though breathing can hurt. Hustvedt says she can meditate her migraines away. I want to get there with her, and I keep trying.

Until then, I tell myself that it is not just love that unites us, but pain, too, and that to deny it is to deny the fact of being human. To me there is the great and lasting solace in that, expanse and connection, even when I’m alone, fathoms deep in my bed. Take this novelist, the visionary Ursula K. Le Guin, writing in The Dispossessed in the voice of a character based on Oppenheimer, father of the atomic bomb, a man who knew regret and its isolations as well as he did his own face: “It is our suffering that brings us together…The bond that binds us is beyond choice. We are brothers in what we share. In pain, which each of us must suffer alone, in hunger, in poverty, in hope, we know our brotherhood. We know it because, we have had to learn it. We know that there is no help for us but from one another.”

Until then, I tell myself that it is not just love that unites us, but pain, too, and that to deny it is to deny the fact of being human. To me there is the great and lasting solace in that, expanse and connection, even when I’m alone, fathoms deep in my bed. Take this novelist, the visionary Ursula K. Le Guin, writing in The Dispossessed in the voice of a character based on Oppenheimer, father of the atomic bomb, a man who knew regret and its isolations as well as he did his own face: “It is our suffering that brings us together…The bond that binds us is beyond choice. We are brothers in what we share. In pain, which each of us must suffer alone, in hunger, in poverty, in hope, we know our brotherhood. We know it because, we have had to learn it. We know that there is no help for us but from one another.”

The post On Migraines, Pain, and Creativity appeared first on The Millions.