A night at the Freud Museum! The idea appeals. I always think twelve hours the perfect length for any holiday. Philip Larkin at his most likable said, “I wouldn’t mind seeing China if I could come back the same day,” and I agree. Packing my case, though, my intent feels heavy. There isn’t the sense of a spree. I think of the bags I took with me when I went to the hospital to have my daughters: bags of hope, bags of fear. I am braced after a month when, deliberately, there hasn’t been a second to think about a thing. I sense the facts vying for position, sour and exacting, after stretches of neglect. Scrutiny beckons, mercilessly. Such a stagey approach to feeling can’t be good, but my mood is odd. I’ve been asking others how I seem, looking in the mirror to try to gauge my state of mind. My dreams have been especially sarcastic.

The museum is situated in the house where Sigmund Freud lived for the last year of his life, with his wife, Martha, and daughter Anna, and their maid Paula Fichtl, after the Nazis drove them out of Vienna on June 4, 1938. The house at 20 Maresfield Gardens is a wide, three-story, red-brick villa. It sits in a prosperous and leafy broad North London thoroughfare, its size and bearing in 2023 rendering it, and the neighboring dwellings, a mini-embassy, a mansionette. It’s the kind of address at which fifteen years ago a drawing room owned by internationally acclaimed musicians might boast two grand pianos, primed for duets. It would be too expensive for them now. The road still throbs with high IQs, but it isn’t glamorous, or if it is, it possesses a drab sort of glamour, tweedy and sedate, like Celia Johnson’s character in Brief Encounter, possibly, with an injection of new tech cash.

I am to spend a few hours alone in Freud’s study when the museum is closed and then sleep in Anna Freud’s bedroom. I’ve brought sheets and blankets and a pillow. I have use of Anna Freud’s bathroom and the kitchen next door. Some supplies have been laid in for me. Leaving my house, I add a box of tissues and a bottle of water to my overnight bag. If I could only get hold of a trailing spider plant, my luggage could pass for a therapist’s basic prop kit.

*

At the end of Maresfield Gardens a florist is selling my favorite pale-pink roses—Sweet Avalanche. There’s something about a pleasant disaster . . . the idea of good trouble . . . I hope my thoughts strike me like a sweet avalanche tonight. I begin to audition various cares to see which might best suit my august location. I don’t want anything routine or banal. There’s a recent loss that has gone undermourned, and it’s beginning to nip at my ankles. There are slights that I’ve batted away, trying for elegance, like a lady in a restaurant sending back a half-cooked piece of fish. I’ve a young friend, brilliant and soaring, but stricken of late, whom I’ve attempted to help a bit as he explodes his life. He assumes our relationship, from my side at least, is one of unconditional love. It’s true I’ve defended him and made his well-being a priority. But it is an error on his part, I think. We planned to speak recently, at his request, and he sent a message through to ask if we might not speak, after all. It didn’t suit that day. He said he was hoping for “a reprieve.” That word appears to have broken something. At a literary festival recently, in front of a banner saying Families; the joy and the misery, or was it Motherhood: the pain and the pleasure, I said I was uncertain about unconditional love, that I thought people spoke of it as though it came as standard and in great supply—but in fact it was rare in the extreme. I cannot always run to it for my own household. (Sigmund Freud said it existed only between mothers and infant sons.) I understand that adolescents need to feel home is a safe place to be your worst self, but to how many can I offer this service? Personally, I showed the best of myself to my parents. It is a theme in my life, currently, that too much of it in- volves gestures that feel like human sacrifice.

And what if my dreams at the museum let me down? They may be low in content; I don’t mean low as in base, for that would in its way be excellent, but humdrum or even slight—I remembered to buy toothpaste! I posted a letter!—and how could I admit to that, even to myself? The night that Sigmund Freud sailed from Calais to Dover to come to London in June 1938 he dreamed, with honor and a burst of courage, that it was not Dover where the ferry docked but Pevensey, where William the Conqueror landed in 1066.

I take the linen to Anna’s bedroom, making the bed up carefully as though for an esteemed guest. The sheets and pillowcases are pink and white and frilled, things my daughters have outgrown, comforting in their way. (The state of convalescence is my true homeland, I sometimes think.) I notice there are five tripods in the corner of the room, one with a large black hood like the abdo- men of an ant in a diagram we learned at school. Long spiky legs protrude. Oh no! Oh well. My insect phobia is reasonably mild. On the other side of the room there is a large black-and-white poster of Sigmund Freud against a red ground, eight or nine times life size, with the accompanying phrase: “It is said that the twenti- eth century person was born on Freud’s couch.” I imagine this scene, and it is a baby in a tiny bowler hat with a furled umbrella and a furled personality that I see.

My father-in-law was psychoanalyzed by Anna Freud for more than two decades in this house. My mother-in-law once told me—in even tones—that when she was first married he used to break- fast every morning with his first wife and their child, then go to see Miss Freud and then on to the Observer newspaper building, where he was editor.

Downstairs in Sigmund Freud’s study the alarms have been deactivated. I’ve permission to wander inside the roped-off areas as long as I don’t sit on the desk chair, which is weak. The chair, made of reddish-brown cracked leather, was designed by the architect Felix Augenfeld. A present from Freud’s daughter Mathilde, it looks Henry Moore-ish, its curves and rounded headrest reminiscent of a slender woman. Augenfeld wrote: “S.F. had the habit of reading in a very peculiar and uncomfortable body position. He was leaning in this chair, in some sort of diagonal position, one of his legs slung over the arm of the chair, the book held high and his head unsupported. The rather bizarre form of the chair I designed is to be explained as an attempt to maintain this habitual posture and to make it more comfortable.”

At home in my top-floor office I write in my father’s desk chair, a small modern wooden chair on rockers, half-upholstered in beige calico, from some sort of be-kind-to-your-back shop, the fabric bearing quite a bit of flesh-colored oil paint.

In Freud’s study I sit and watch the scene before me as though it were a sitcom or stage set, awaiting actors. The couch with its five cushions and carpet-style cover and thin gray blanket with S.F.’s coral-colored appliqued monogram has a great deal of presence. I sit on it for a moment and then lie down and feel foolish. I am aware the museum’s security guard is glued to the CCTV. Might he have some sensible advice for me? Anna Freud said to my father-in-law, “I believe in sense as opposed to nonsense,” but I’m not so sure. I get up from the couch and take instead a seat in the green velvet chair where Freud sat to listen to his patients. I feel more comfortable there. I am reading La Peau de Chagrin, the novel that made Balzac’s name, the last book Sigmund Freud read. A young man, in a state of suicidal desperation, has entered a casino and is “standing there like an angel stripped of his halo, one who has strayed from his path.” The casino itself is unpromising. In my experience they are places where people go to feel numb. This one is an icy-hearted arena. “The walls covered with greasy wallpaper up to head height, show nothing that might refresh the spirit. There is not even a nail there to make it easier to hang one- self.” It is a place where “grief has to be muted” and “despair must behave in a seemly fashion.”

Business as usual, then.

In the study, because there is for the first time in the museum’s history a small exhibition of paintings by Lucian Freud, my father, a picture of my grandmother hangs over Freud’s couch, to thicken the plot. My father nursed a sort of abstract respect for the seriousness of psychoanalysis but considered it “unsuited to the lifespan.” Still, we sometimes discussed it. He once asked me, when I was sitting for him, whether it had any ideas or helpful suggestions when it came to the handling of obsession, whether this was something that had been addressed in my own therapy. He was talking, I knew, about matters of the heart. I was twenty-one at this point, and he was sixty-eight. I was touched by this opening seam of humility. “The thing about obsessions, if you ask me,” I began, “is that they tend to occur when there is something else pressing that you’re trying really hard not to think about.”

“Oh?”

“The trouble is, of course, that the obsession quite quickly can cause more pain and difficulties than the original thing you’re trying to avoid.” I could tell instantly it wasn’t the answer he wanted. I knew he had visited my elder brother at a rehab center recently, where he was trying and trying not to beat a heroin addiction. There my father had attended a small meeting with some gathered support staff where he was told, “Alex’s problem, apart from drugs, is that he is addicted to obsessive love.”

“But surely obsessive love returned is the finest thing a man can feel,” my father hotly defended his son.

*

In the painting above Freud’s couch, my grandmother is lying fully clothed—beautifully dressed—on a bed, her arms splayed at her sides in the “Don’t shoot” position. It’s the attitude in which both my daughters slept when they were newborn. The fabric of her paisley dress looks luxurious, stately; and the material of the bedspread—intersecting white arcs and little textural curved lines of holes as in a hemstitch pillowcase or huck towel—is tender and modest. The bed has iron bars like the beds in a hospital or con- vent. Sigmund Freud was impressed with my grandmother. They got on well, and she was clever. It meant a great deal to Lucie that her father-in-law admired her and enjoyed her company. It was Lucie who insisted her family leave Berlin in 1933. I met her just once, when I was visiting my father at 36 Holland Park. You rang the bell that discreetly read top flat, and then there were about seventy steps. I paused and said good morning as I passed her on the stairs. I think I would have been about fourteen. She smiled. Did she know who I was? She looks at home lying here. I get back on the couch again and look up at her in her frame and feel for a moment as though we’re about to meet on Zoom.

*

On March 15 the Gestapo raided Sigmund Freud’s home at 19 Berggasse. The Professor was recovering from recent cancer surgery, and his wife, Martha, to defuse the stress and terror of the situation, asked the men if they’d care to leave their rifles in the umbrella stand. Might they like to sit down? These friendly and hospitable gestures did help calm things a little. It’s a scene I often think of, extreme politeness being a useful resource in dreadful situations. After Freud left his home on June 4, 1938, on the 3:55 Orient Express, traveling first to Paris and then to Dover by ferry and then to London, the Nazis changed the function of his building to “collection apartments,” and approximately eighty Jews were imprisoned there to wait for deportation to concentration camps.

*

I knew Freud’s study to be grave and masculine, but I had not expected such a climate of sadness. Why hadn’t I? Time has a strange quality here. It gallops and leaps when I assumed it would drag. I

think of the clock melting in the Terry Johnson play Hysteria, which is set in this study. Fifty minutes passes in an instant, then another fifty and another. It’s as though there’s an impatient quality to the atmosphere. No room for anything inessential. My concerns are trivial here. The study is peopled by a cast of hundreds: the antiquities, heads and figurines that adorn most of the cabinets and surfaces, which arrived from Vienna along with other essentials such as Freud’s couch in the first week of August 1938. The figures can’t help but make you think of refugees.

The scent is of old leather, and there are wan notes of tobacco or something more mysteriously smoky like Lapsang souchong tea or the remnants of a bonfire, the foggy brown smell that still thickens the air for twenty-four hours after fireworks have been lit. French windows with their long red theatrical curtains almost appear to invite intruders. Freud treated a small number of patients and continued to write here until August 1939. Although his architect son, Ernst (my father’s father), installed a small lift in the house, at the end of his life Freud slept in this study and a second couch was purchased for him to lie on, an invalid couch with a vivid botanical print and better orthopedic support, from a specialist shop in Great Portland Street. He liked to look through the windows at the roses in the garden, which delighted him and were not visible from his upstairs bedroom. I try to think about what it would be like to lose your home, your state, your patients, your siblings, the city where your mother tongue is spoken, half your books, and many other aspects of your identity at eighty-two, when you were already suffering the long-term effects, in terms of both symptoms and treatment, of jaw cancer. Even Freud’s dog avoided him at the end, disliking the smell of the disease. There was much to be mourned. Arriving in London he wrote to the psychoanalyst Max Eitingon, “The feeling of triumph on being liberated is too strongly mixed with sorrow, for in spite of everything I still greatly loved the prison from which I have been released.” Freud died in this room. There are many ghosts here. Four of Freud’s five sisters perished in the camps: eighty-two-year-old Rosa, eighty-one-year-old Marie (Mitzi), and seventy-eight-year-old Pauline were murdered at Treblinka in September 1942; Adolfine (Dolfi) died at Theresienstadt, aged eighty. My father’s great-aunts.

*

I go upstairs and get into the little childish bed in Anna’s room. Sleep is out of the question. The giant insects taunt me; the enormous Professor looms, with loss suspended bleakly in the air between. It is cold, and I am in all my clothes. What do you think you’re doing? I ask. I get up, find a cupboard—and this is so unlikely it feels like a mirage—it is stuffed with packets of biscuits! I open a pack of Bourbon creams and eat five very fast. Why not? They were the medicine of my childhood. I redo my teeth and get back into bed, which now smells sugary and has dark crumbs.

My thoughts turn to the woman I used to see three times a week in the adolescent department of a nearby psychoanalytic clinic. I was twenty-one, bereaved, and reeling and felt as though the universe was trying to finish me off. She was high-spirited, rigorous, greathearted, and treated me so well I began to see myself differently. Jeannie, she was called, Jeannie Milligan. She dramatically altered my life chances.

An episode comes back to me in the narrow pink bed. For one of our sessions, the only time it ever happened, she was fractionally late, about one hundred seconds. She apologized and asked me if it would be possible and convenient for us to add the missed portion on at the end. I remember analyzing her words as though they were a poem. (I was a third of the way through an English degree at Oxford but had taken half the year off owing to “circumstances.”) Not only was she acknowledging the lateness and apologizing for it—lateness I knew another would scarcely see or feel—she was offering to make reparations. More than this, she did not assume her plan would suit me, for I might conceivably have to be somewhere immediately afterward and be unwilling to pass this infinitesimal lateness on. I could tell she was keen to iron out any possible sting of rejection. Yet there was none of the humiliation that attaches itself to “treatment,” no hint I was a trem- ulous invalid, perched on precarious cliffs. It was merely a putting right, almost automatic, as one might straighten a chair or pat dry a plate. What courtesy! It contrasted so dramatically with a long period in my life when my father used to telephone regularly and ask me if he could speak to one of my older siblings.

Once or twice during the many years I saw Jeannie, she issued sentences of profound approval that still wallpaper the inside of my head. “You were very brave,” she said to me. Another time: “However bad you felt, you never stopped working.” Medals for courage and grit and grafting! I saw her on and off for three decades, sometimes with gaps of several years. In some respects she was a third parent to me.

Our very last conversation had notes of farce. She was retiring. “I have to ask you something. I am in good health now,” she said, “but if I were to die would you like to be notified?”

I nodded. “And if appropriate I’d like to come to your funeral if I may.”

“Yes,” she said, “yes, after all we’ve been to each other.”

“And . . . and if I should predecease you, would you want to be notified?”

“Yes.”

“And come to my funeral?” She nodded, in symmetry.

We peered at each other in the shadows of this extremely odd conversation.

“Well, see you there then!” I said.

I almost added, “I think psychoanalysis is an unrivaled method of human understanding, but I do occasionally wonder if its theories apply a little more to the Freud family than the population at large.” But there was no time to introduce new themes.

I Google her from Anna Freud’s bedroom on my telephone, wondering if there is any news. I would so love to see her again, but I know it isn’t possible. She knew me before I built myself. She saw the tenor of the raw materials; the things that needed to be discarded; the new hardware that had to be acquired. The swathes of unfactual landscape we swept away together!

On the little screen suddenly—there it all is again—no description of upcoming talks and publications, just the facts with their nightmarish proportions. She had perished alone in a house fire, months earlier. I don’t open them, but there are films of her burning home on the screen. Our parting agreement, that she would not die without telling me, must have gone up in flames. It was the wrong ending entirely, savage and Victorian, for someone who gave so many young people a magnificent start in life. You can feel guilty of treachery when someone you’re crazy about dies. I feel it now. You did everything for me, and I couldn’t even spare you this.

But there are also wonderful obituaries and rapturous tributes . . . a pioneer in combining the disciplines of social work with psychoanalysis . . . a loyal colleague and loving friend . . . everything she gave, her sense of humor and her sense of justice . . . tremendous vivacity and glamour . . . the star of the annual pantomime, singing and dancing and acting with sheer brilliance and utter captivation.

I think of wandering down into the study again, but the alarms are on now and all the lights are off, so I gaze up at the picture of Sigmund Freud on the wall, and then I hear myself apologize.

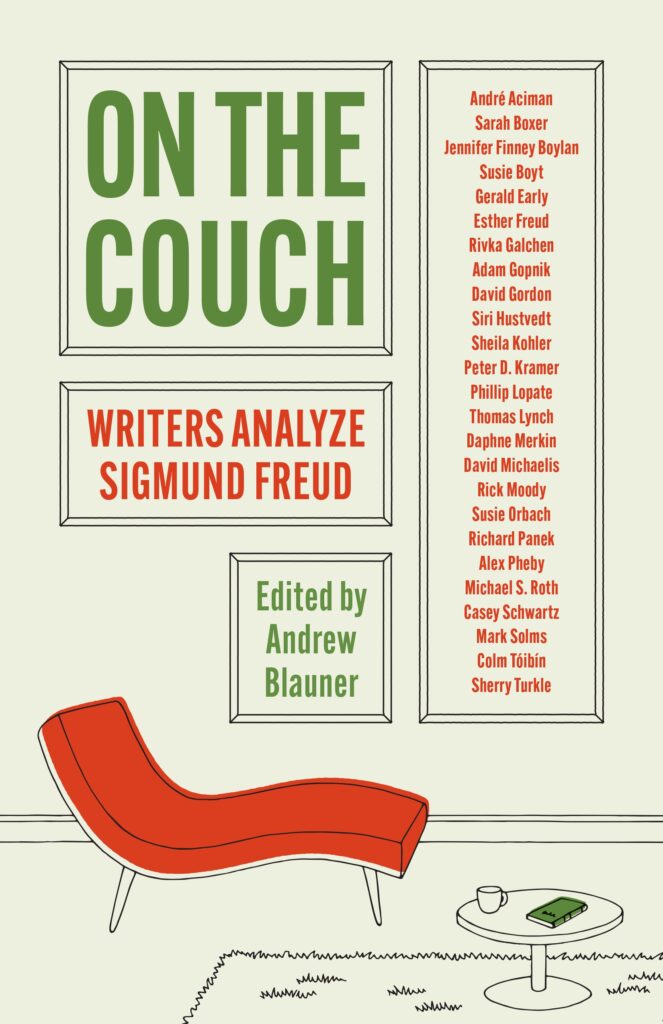

Excerpted from the anthology On the Couch: Writers Reflect on Sigmund Freud, edited by Andrew Blauner published on May 14, 2024 by Princeton University Press.