All too often, we find ourselves wishing we had said or done more when we lose someone, no matter the circumstance. That is the very nature of grief: It leaves us feeling robbed, of time, of memories that will remain unmade. But while all of us have known or will come to know grief at one point or another, calling it—or death—the great equalizer is imprecise. Because even though we all reel from loss, the catalyst of that loss is, more often than not, a primary texture of the grief we feel as a result.

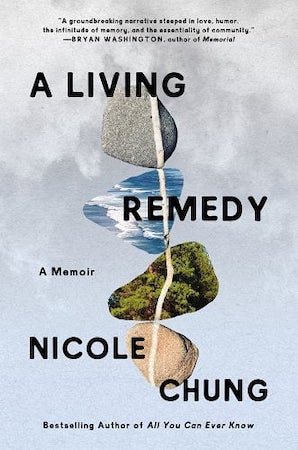

In A Living Remedy, Nicole Chung parses her grief in an effort to identify what remains out of her control, and what she can reconcile in her own world, all in an effort to find a way to co-exist with it. Her father was only 67 when he passed away from diabetes and kidney disease. She barely begins to contend with the grief and rage she feels as a result of his death, knowing that inaccessibility to healthcare largely contributed to it, when her mother is diagnosed with cancer less than a year later, right before the COVID-19 pandemic. Grappling with distance has always occupied Chung’s mind ever since leaving her primarily white Oregon hometown for life and study at a private university on the East Coast, but as the pandemic descends upon the world, forcing much of it into isolation, she must also face being unable to be at her mother’s side as she dies.

In this tenderly crafted, powerfully deployed memoir overflowing with heart and humor, Chung tries to navigate grief without punishing herself for the things she has no control over. These are the same things millions of Americans have had to confront when caring for sick loved ones, and will continue to do so for as long as healthcare is seen as a privilege, and not a basic human right. As she learns, and teaches us, grief—in all its forms—is not something to push away. While it’s not something we welcome, it’s not an enemy either.

Greg Mania: I can’t help but think of this memoir as not one of grief, but one of memory, of living with grief and filling the seemingly endless chasm it leaves in us with echoes of life lived, even beyond death. You even write, “It’s not a presence, exactly. But not an absence, either.”

Nicole Chung: I remember being so afraid that losing my mother would feel like losing my father again, too. That they would both feel far away, forever unreachable. As deep as my grief was, and is, that hasn’t happened.

It still surprises me how close they feel. I don’t mean that I picture them drifting above or behind me, my personal ghosts, always tuned into the Nicole Channel—but I can say that I feel their love like a living thing, still with me, in the present tense. I love what you say about the book being one of memory, not grief. I might add that, for me, memory is the part of grief that feels most alive, and has proved to have the most staying power. It’s always with me, and so, in that sense, they are, too.

GM: I don’t think one is ever truly “ready” to write about grief, loss. If not the “right” time, what would you describe the time leading up to writing this book? What did you feel called by?

NC: I shouldn’t say “my book contract,” should I? LOL!

First, I should say that I didn’t know whether I could write this book. I sold it a year before my mother died and several months before she received a terminal cancer diagnosis. I’d imagined that the story would focus on my grief for my father and the injustice of when and how he died, and that my mother would be here to talk with me about it and read it when it was done. I never thought I would be writing about losing both my adoptive parents in a two-year span.

After she died, I put the manuscript down for a while. I knew the entire project would have to be reimagined, I would have to start over from the beginning, and I just did not have the energy for that kind of endeavor in the days or weeks following her death. There were days when I didn’t know if I’d ever feel right going back to it. I wrote in my journal, I started taking on freelance assignments again, sometimes I took notes or did some research for the book, but I didn’t touch the manuscript.

We are living with so much unacknowledged grief, personal and collective. I don’t think we can, or should, look away from that pain so many have experienced.

In late 2020, I took what I could from chapters I’d already drafted and started over. I wrote a brand-new first chapter. I realized that I knew where I wanted to end the book, but had no idea how I would write my way there. I wasn’t happy with my writing progress throughout much of 2021. The turning point was probably when I quit my full-time publishing job in October 2021. I’d finally accepted a truth I had been resisting: I couldn’t work that particular job and write this particular book. Editing and managing a team took up all my time and most of my creative and mental energy as well, and the pandemic did not help. Another opportunity came along—one that would prove to be a lot of work, too, but it left me with more space for writing, and things finally started coming together (although I did not believe this until trusted readers began telling me so). I wrote the last third of the book over two weeks of marathon writing sessions during my holiday break.

I got to a point where I felt a kind of wonder and curiosity about this story, as hard as it was to write. I was living through some of the events in this book, writing about my grief in real time. It was all new to me. With my first book, I knew everything that would be in it when I sat down to write, even if it changed a lot in the writing. With A Living Remedy, I had some pieces set, but I truly didn’t know where it was going for a long time. That was really scary, and then, finally, the fear was joined by these questions that consumed me: What was I learning, about myself and about my writing? What was most important to me in the aftermath of my parents’ deaths? Could I write a book about grief, about my family, that would matter to or help other people? It was a leap of not-quite-faith, and I had to learn to trust myself as a writer in a way I hadn’t before. In the end, I felt really free in the writing of this book—and that’s why I say that it’s my whole heart. That’s what it required.

GM: You also write about the collective grief the world has come to know in some way, shape or form in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic—when knowledge was limited, testing was scarce, and no vaccine was in sight. Has this period helped you usher your story onto the page in some way?

NC: I’m not sure I know the answer. I know that when my mother was dying in March, April 2020, no one in my life had to stretch terribly far to understand my sadness and fear. I did not want to write a pandemic book; it only comes into the story in a couple of chapters. But it felt important to try to capture those feelings, to document what it was to lose someone you love in the early days of the pandemic. We are living with so much unacknowledged grief, personal and collective. I don’t think we can, or should, look away from that pain so many have experienced—are still experiencing. I don’t think we should forget it.

GM: You masterfully illustrate the anxiety I think a vast majority of our generation is grappling with when it comes to wanting to take care of our parents when they get older, but might not be able to—at least now in the way we would like—because of financial instability. How were you able to reconcile what you could do, and what you were unable to? Asking for me and literally all of my friends who are kept up at night because of this.

NC: It’s so hard. Intellectually, you can know that you are not to blame for your family’s circumstances, but a part of you still feels responsible for them—you always want to support and protect and help the people you love. I don’t know if I’ll ever be able to fully reconcile what I could and couldn’t do for my parents. I do know that they never thought of our relationship as a ledger, and weren’t keeping track of my failures or holding anything against me. Until the end, my mother, especially, thought of taking care of me, and resisted the inverse for as long as she could. I don’t know how she did it—I guess it was just the steady love she had for me—but after she died, I understood that she didn’t blame me, and wouldn’t have wanted me to blame myself. I was able to learn how to grieve for her without punishing myself.

Telling the story of my adoptive family and the story of my grief meant naming and confronting these injustices.

With my father, who fell through the safety net, whose death was sped up by a lack of healthcare, it was harder to come to terms with all that I couldn’t do. I grew up thinking of my parents’ future needs and care as my responsibility, part of what I owed them as their child. I think a lot of people feel this way. And that might work—if you’re privileged enough, wealthy enough, live or can move near your parents or have space in your home for them, don’t need to work all the time, don’t have children with significant needs of their own, and you all have health coverage. Even then, it’s hard; it’s expensive; it takes time and energy and the kind of planning that is really hard to do without knowing the future. We leave people without the resources and support they need, making them feel that it’s all on them to provide and pay for their loved ones’ care, even when the need far outstrips their capacity. There’s this focus on personal obligation or responsibility that doesn’t acknowledge the reality. I still have to remind myself that this is a lie—that I was not responsible for structural failings, or the systems that failed my parents. That my dad’s loss was tragic, and unfair, and also one of too many like it in this country.

GM: You write about the last time you saw your mother, and the exchange you two had about forgiveness. You mention how that brought you something akin to peace, if not closure. But I feel like when we lose someone, there will always be something left unsaid of some varying degree. Do you agree, and if so, how do you make space for those things we wish we could have said, or expressed, in your heart?

NC: There is much I would change about my final months with my mom, but I’m very fortunate in that I don’t have to wonder about or regret the things I didn’t say to her; I really tried to say everything I needed to at that time, and I think she did as well. But I know what you’re talking about, and I do think it’s quite common. When my dad died, there were definitely things I wished I had been able to do, or say.

I don’t know if this will be of any use to anyone else, but occasionally I will write a letter to one or both my parents. No one sees it but me. It’s just a way of telling them something I want to tell them, releasing that on the page.

GM: I think many, if not most, of us, myself included, share your rage at how appalling our healthcare system is. Anything but universal just comes with a death sentence for many, because so many of us literally cannot afford to get sick. How have you channeled your anger over a healthcare system that is basically an obstacle course that offers a fast pass to those who can afford it?

NC: Americans, even insured Americans, spend so much money on healthcare. It’s one of the most expensive systems in the world. And it’s a case of not getting what you pay for: many people don’t have enough coverage, struggle to navigate an overwhelming health bureaucracy, and then still don’t get the care they really need. We have to keep talking about this, advocating and voting for better policies and systems that won’t leave millions behind.

Grief is not something I feel a need to avoid, to push away, any longer. The closer it is, actually, the better I can live with it.

Though this book doesn’t represent any personal catharsis for me, I did channel a lot of my fury into the writing of it. Telling the story of my adoptive family and the story of my grief meant naming and confronting these injustices. I generally don’t believe in prescribing lessons to readers; I want people to take what they will, what they may need, from this book. But from my own experience as a reader, I know that stories can help us reconsider things we already know, as well as things we may not know how to confront. The personal can show us a new way into a much larger issue or problem. If this book helps some readers do that, or helps those who have gone through similar experiences feel less alone, I will be glad.

GM: I love what you said about channeling a lot of your fury into writing this book. I think anger is—and I’m sorry, but this is the first phrase that came to my mind—a great lubricant for releasing the things that sit heavy on our hearts and minds. Do you feel like now you can hold space for your anger in a way that doesn’t feel like it’s bearing down on you?

NC: For me, writing didn’t do that. It was mostly time, and seeing a therapist to talk about my grief. And I think I really had to do that before I wrote, rewrote, whatever, much of the book, because if I hadn’t my guess is that it would have been impossible to complete it.

Early on, before my mother got sick, I’d drafted some pieces about my dad’s death and showed them to an editor friend, who told me, essentially, “I think you’re being too hard on yourself.” She was right—in that case, it was my anger at myself surfacing in ways I hadn’t noticed in the text. Not that there can’t be a place for that in your writing, but at that time, for me, most of it wasn’t conscious or controlled. It made the writing suffer, and I believe was a sign that I needed to do some more work and take some more time.

I’m not sure that writing allowed me to hold space for my anger. That required other, personal, deliberate effort. I had to give myself permission to be angry in my grief for both my parents, and at the same time stop blaming myself for things I couldn’t have changed. As for my rage with the systems that failed them, I could channel some of that into my writing, but had to do so in an intentional, controlled way—you know where water in a channel is going; the destination isn’t a surprise to you. I had to know what the anger was in service of, what part it had in the narrative, in order to write about it in a way that would translate to readers and bring them along.

GM: How has your relationship to grief changed since writing this book, if at all?

NC: I’d like to be able to say that I know everything about my grief now, its weight and its dimensions, and that it won’t sneak up or surprise me again. Of course, that’s not true. It’s less because of the writing, and more because of the time I spent doing the active memory work a story like this requires, but I think I’ve grown more used to living with memory, as you put it earlier. Grief is not something I feel a need to avoid, to push away, any longer. The closer it is, actually, the better I can live with it.