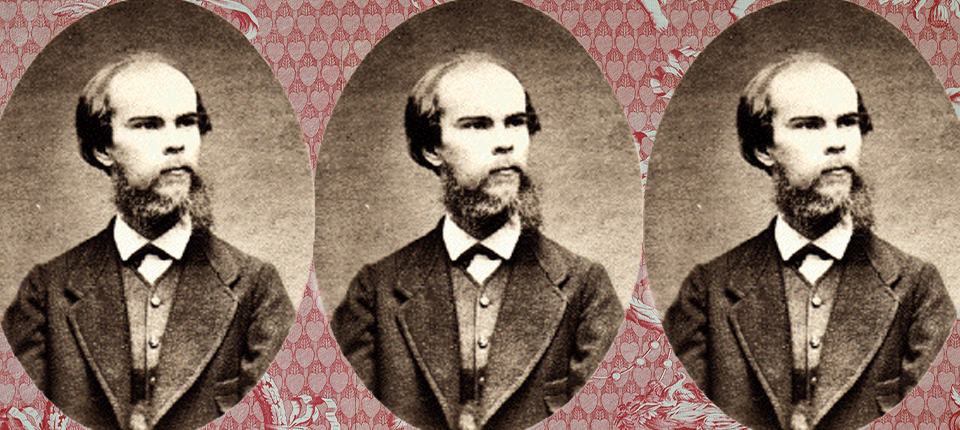

In 1846, still basking in the success of “The Raven,” Edgar Allan Poe published an essay titled “The Philosophy of Composition,” in which he claimed to give readers a behind-the-scenes look at how it’s done, specifically how “The Raven” was done. He describes a painstaking, almost mathematical process; declares the death of a beautiful woman as “the most poetical topic in the world”; reveals that the sonorous refrain of “Nevermore” was chosen purely for its sonic properties; determines that 100 lines is long enough for a poem to engross the reader while short enough to be read in a single sitting; and so on. Writing a great poem is a series of calculated decisions, Poe tells us.

When Bob Dylan titles his new book The Philosophy of Modern Song, you have to wonder if it’s another nod to Poe, whom he references in Chapter 24 (as Stephen Foster’s counterpart), as well as in his 2004 memoir, Chronicles, Volume One, and his recent song “I Contain Multitudes” (“I got a tell-tale heart, like Mr. Poe”). Yet Dylan’s Philosophy is nothing like Poe’s. He doesn’t describe his own process. He doesn’t write about the mechanics of songwriting much at all—meter, rhyme, chord progressions, verses, choruses, and bridges are not what this book is about. He doesn’t write about the history or evolution of pop songwriting (the chapters aren’t chronologically sequenced) much less about how he changed it forever. He doesn’t write about any of his own songs. He doesn’t write about the songs of contemporaries with whom he’s most often compared—Leonard Cohen, Joni Mitchell, Paul Simon, the Beatles.

When Bob Dylan titles his new book The Philosophy of Modern Song, you have to wonder if it’s another nod to Poe, whom he references in Chapter 24 (as Stephen Foster’s counterpart), as well as in his 2004 memoir, Chronicles, Volume One, and his recent song “I Contain Multitudes” (“I got a tell-tale heart, like Mr. Poe”). Yet Dylan’s Philosophy is nothing like Poe’s. He doesn’t describe his own process. He doesn’t write about the mechanics of songwriting much at all—meter, rhyme, chord progressions, verses, choruses, and bridges are not what this book is about. He doesn’t write about the history or evolution of pop songwriting (the chapters aren’t chronologically sequenced) much less about how he changed it forever. He doesn’t write about any of his own songs. He doesn’t write about the songs of contemporaries with whom he’s most often compared—Leonard Cohen, Joni Mitchell, Paul Simon, the Beatles.

A book by Bob Dylan about all those things might have been

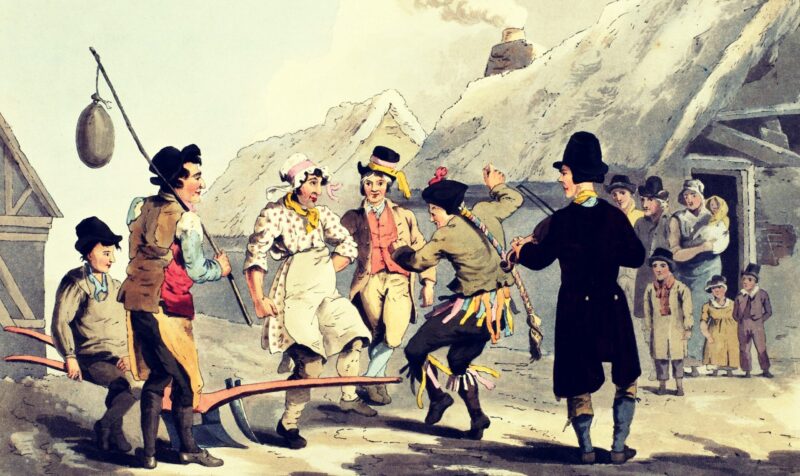

great, but this book is great largely because it avoids all those things. Fans of Theme Time Radio Hour, the show Dylan hosted from 2006 to 2009 (revived for single episodes in 2015 and 2020) will feel at home with The Philosophy of Modern Song. TV producer Eddie Gorodetsky, who lent his legendary record collection and producing skills to Theme Time, is the first person Dylan acknowledges on the dedication page, “for all the input and excellent source material,” which I suspect is well-earned gratitude. Theme Time episodes romp across popular music history and genres, with Dylan riffing on any given episode’s theme (weather, cats, baseball, mothers, whisky) as well as the mix of obscure and famous recordings. Here, Dylan riffs on 66 songs; most chapters consist of an impressionistic section followed by a more sober reflection that often includes information about the songwriter(s) or performer but just as often veers off into amusing tangents concerning keys, technology, or songs about fools. Wonderful archival photos abound—of performers, record stores, and imagery evoked by the songs. (There are a few nice visual puns, like the photo of Julie London holding a telephone receiver in the “London Calling” chapter.)

These are a fan’s notes rather than a songwriter’s secrets, and even though we already knew that Dylan’s musical taste is more eclectic than the average 81 year old’s, his appreciation of everything from vaudeville to blues and honky-tonk to soul and punk is pretty inspiring. Writing frequently in the second person, Dylan rarely analyzes lyrics but instead describes how these recordings make him feel, elaborating on the scenarios they present. In a chapter on Harold Melvin and the Blue Notes’ “If You Don’t Know Me by Now,” he imagines the singer getting into bed with his “steady mate” after arriving home late:

On goes the light, and she wants precise details of where you’ve been, and she’s giving you the business, giving you bad vibes. You try to be cool, but she’s cagey and skeptical. You’re here body and soul, why can’t she get the hang of that. You’ve given her everything you can lay your hands on, and she still can’t tune in to you. If she doesn’t know you by now, she must be mindless.

He skirts the issue of whether her suspicions are justified. Writing about a song of seduction, “Come On-A My House” sung by Rosemary Clooney, Dylan seems more interested in what literal food might be on offer, particularly various kinds of cake. When he turns back to the metaphorical, he sees Clooney’s invitation as more than a sexual come-on: “This song is gesturing at you to discover yourself. It’s coaxing you, enticing you to come out of retirement and jump in. Are you tempted? You bet.”

Dylan makes no pretense of a ranked list, thank goodness, nor does he argue that these are the “greatest” songs of the modern era. They’re just 66 songs that he loves and wants to write about. Twenty-eight of his picks are from the 1950s, which makes sense when you recall that Dylan went from ages nine to 19 over the course of that decade. In the 1959 Hibbing High yearbook, he listed his ambition as “To Join Little Richard,” so it’s not surprising that “Tutti Frutti” and “Long Tall Sally” are here. Elvis’s version of “Money Honey” and Carl Perkins’s “Blue Suede Shoes” are featured as well, but Dylan is equally interested in the country and pop music of the fifties: “There Stands the Glass,” “Your Cheatin’ Heart,” “El Paso,” “You Don’t Know Me,” “My Prayer,” “Without a Song,” “It’s All in the Game,” even “Volare.” No other decade gets half as many chapters, which reinforces the sense that Dylan’s own records, which seemed so unprecedented in the sixties, were forged in both the marginal and mainstream sounds of the fifties.

While Dylan’s project is ostensibly not a memoiristic one, inevitably there are oblique self-references. He notes that when Elvis Costello performs “Pump It Up,” Costello gives away that he “has obviously been listening to Springsteen too much. But he also had a heavy dose of ‘Subterranean Homesick Blues.’” Later, the songwriter who became famous for socially conscious anthems, and then famously swore off them, praises Norman Whitfield and Barrett Strong’s “Ball of Confusion” (recorded by the Temptations) as “one of the few non-embarrassing songs of social awareness.” But he seems skeptical of Whitfield and Strong’s sincerity in his chapter on “War,” the Edwin Starr hit: “‘War’ obviously filled the coffers at Hitsville USA but, then again, war was usually good for business.” Elsewhere, he makes the case for Marty Robbins as a man with a message: “People talk about message songs, starting with Woody Guthrie and right up through the sixties. But ‘El Paso’ is the ultimate message song, and reflective words would only hope to scratch the surface.”

Dylan embodied youth culture in his first decade as a performer, telling old people to get out of the way in “The Times They Are A-Changin’”; ridiculing the square, over-30 Mr. Jones in “Ballad of a Thin Man”; and offering the wish that we stay “Forever Young.” But things have changed. Appropriately, Dylan’s twenty-first-century albums reflect the wisdom of age and memory, and he wisely makes no attempt to embrace new musical styles or to make his voice sound youthful, or even middle-aged. He’s old, dammit—you got a problem with that?

A chapter on Charley Poole’s 1928 classic “Old and Only in the Way” becomes an eloquent complaint on the way old people are treated and the inability of even well-meaning young songwriters to grasp it. We get glimpses of this particular old man’s preferences in other chapters; a discussion of Willie Nelson’s “On the Road Again” leads him to this conclusion: “The thing about being on the road is that you’re not bogged down by anything. Not even bad news. You give pleasure to other people and you keep your grief to yourself.” It’s as good an explanation as you’re likely to read of why this particular octogenarian spends as much time as possible on tour.

Ultimately, The Philosophy of Modern Song is less about songwriting than about performance—or it might be more accurate to say that Dylan refuses to separate the two. Each chapter title announces the performer in the same large font as the song’s title, with songwriters’ names in smaller print underneath—no accident. He occasionally discusses different versions of these songs but focuses on specific recordings, and about half the time the songs are not performed by their writers. Regarding his own work, he made a similar point in his 2016 Nobel Prize speech, that like Shakespeare before him, he writes for performance, not for the page. In a wonderful chapter on “Black Magic Woman,” he scolds those who focus only on the printed word: “All the self-styled social critics who read lyrics in a deadpan drone to satirize their lack of profundity only show their own limitations.” The same might be said of people who insist that Dylan’s lyrics are—or aren’t—poetry.

That emphasis on performance defines Dylan’s aesthetic: the

exhilaration that he exhibits throughout the book comes from perfect marriages of song, singer, and arrangement, and most of the time, those arrangements are spare. “If Hank [Williams] was to sing [“Your Cheatin’ Heart”] and you had somebody like Joe Satriani playing answer licks to the vocal, like they do in a lot of blues bands, it just wouldn’t work and would be a waste of a great song,” he writes. “Enjoy your free-range, cumin-infused, cayenne-dusted heirloom reduction. Sometimes it’s just better to have a BLT and be done with it.” And the music of blues singer-guitarist Jimmy Reed, he writes, “is about space. About air being moved around the room. . . . You put him with Jimmie Rodgers and Thelonious Monk, two other musicians whose work never sounds crowded no matter how many players are there.” Space, simplicity, freedom: these are the principles Dylan returns to throughout the book.

In the coming weeks, we’ll probably see lists of sentences and phrases in The Philosophy of Modern Song that were, like the book’s title, lifted from other sources. This is generally how Dylan, who also crafts gates out of found objects he welds together and creates paintings based on movie stills, works these days. Indeed, there is a kind of stitched-together,

secondhand feel to his sentences, in which overwrought or arcane phrases magically come to life in this new context. Wherever the research or the phrasing comes from, what we hear throughout the book is Dylan’s exuberance, an enduring excitement for records he loves. Sonny Burgess’s “Feel So Good” represents “the sound that made America great”; “Keep My Skillet Good and Greasy” by Uncle Dave Macon “melts everything down, browns it up and deep-fries it—it’ll milk the cow till it gives blood.” Reading our greatest songwriter tell us how these recordings feel to him, paying tribute to the music that moves him, can’t help but inspire us to listen with wide-open ears to these 66 songs—and all the songs we love.

![Watch ‘911’ Season 6 Episode 9: Bobby’s Sponsor Wendell Scene [VIDEO] Watch ‘911’ Season 6 Episode 9: Bobby’s Sponsor Wendell Scene [VIDEO]](https://tvline.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/911-season-6-episode-9-bobby-video.jpg?w=620)