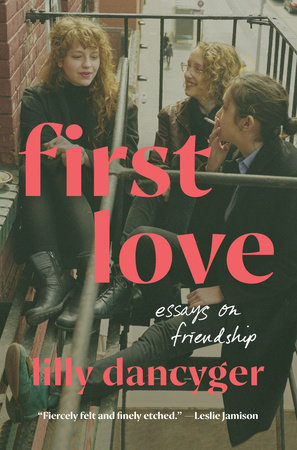

Pop culture feeds on romantic couplings, but we all know the truth about who keeps us alive. Our friends, what would ever we do without them? It is passionate platonic friendship that concerns Lilly Dancyger in her second book, First Love: Essays on Friendship.

A collection of personal and critical essays, First Love began when she was writing her first book, Negative Space, a memoir about grieving her father, later selected by Carmen Maria Machado for the Santa Fe Writers Project Literary Award. “I was writing a chapter about my teenage life, when I was getting into drugs,” Dancyger tells me. “And there just wasn’t room to go into the relationships that were so important in my life at that time.” She promised herself she would return and write about them later.

Today that project is here: it tastes of whiskey and smells like cigarette smoke, and inside, reveals a tender heart roaring with loyalty. Each new essay on friendship reads like its own little universe, “with its own history and customs and themes and flavor,” she says.

I spoke with Dancyger via phone about why love is softness, the problem with murder memoirs, and that gush of pleasure we get when a book all comes together at the end.

Amy Reardon: I love this sentence: “We snarled and bristled, puffed ourselves up and bared our teeth, but only to protect the softness we’d made for each other where no one else had.” Can you talk about the tenderness and softness at work in this project?

Lilly Dancyger: In that piece, I’m talking about the group of friends that I had as a teenager. We were the bad kids, we were degenerate getting into trouble, drinking a lot, shoplifting fighting. We were like dirty, grungy street kids that I don’t think people generally associate with softness, and softness was not what we showed to the world. I wanted to remind people or tell them, for the first time if they had never thought about it, that kids who act out like that are doing it for a reason. They need that softness. Those friends and I made that for each other. That was lifesaving.

AR: In the essay, “Partners in Crime,” you write about two young girls who create themselves around each other. So much so that they start to look alike. Why do you think?

We figure out who we are in the world in the context of our friends.

LD: It’s an experience that a lot of people have. We figure out who we are in the world in the context of our friends. First you have your family of origin, and that’s the beginning of learning who you are and how you fit in the world. But then a big part of growing up and developing is differentiating yourself from your family. Striking out on your own, you find your peers. It’s also a dangerous time for a lot of kids. That’s what peer pressure is all about. Kids get into all kinds of trouble and sometimes go down destructive paths because teenagers really want to fit in with their friends. That’s often talked about as like a kind of a psychological weakness in young people, but I think it’s inevitable and natural because how we establish our identities in the world. Ideally, or hopefully, there’s another phase of differentiation later when you realize you don’t have to go along with a crowd, and you figure out who you really, truly are as an individual.

AR: In “Portraiture,” a photographer friend sends the narrator a mini-essay about why she shoots photos of her so often. Here she is describing years before, when the narrator was a bartender:

“You kicked out grown men, and they complied. One night, some guy I’d been talking to eyed you from across the bar, cocked his head and commented on how hot you were, as if he was the first person to ever notice, like he’d discovered you. I wanted to laugh in his face.”

Her words sort of took my breath away. How did it feel when you read that and why did you choose in include it in the collection?

LD: That took my breath away too. I thought it was so lovely, and also unexpected. That’s not what I asked her for. We were talking about collaborating on a photo project, and I thought she was going to send me some ideas for some images. And she sent me this really loving and seeing description of a past version of myself. It also got to the heart of a lot of what I was trying to talk about in the whole book, which just how clearly we’re able to see each other, even when nobody else can or nobody else wants to. She sent me that and I was like, well, shit, I’m falling short in all these other essays. Nothing I wrote in the rest of the essays is as perfect as this. That’s a good feeling.

AR: I love how this book is about mostly straight women, with all kinds of loving and hurting and hooking up going on, and the men are never the point. I’m guessing that was intentional?

LD: The book is not about them. I do have some really close friendships with men too, and there was a point where I was like, should I write about them? Or maybe even put one essay in here about my closest guy friend who was my best man at my wedding. But it took away from what I was really trying to talk about, which is the love between women and all of the different shades of it.

AR: The scenes in this project are rendered so sensually—they actually taste like whiskey and smell like cigarette smoke.

LD: I really wanted to write something about the role of alcohol in my social life. It was only when I [was editing and] zoomed in that I really realized just how often I mention whiskey. But I left it in because that’s authentic to my experience. I was a pretty heavy drinker from the age of 14 to about 27ish.

AR: Then at the end of the collection, the narrator’s going to bed early, sober with a cup of herbal tea.

There’s always kind of a scary vulnerability to putting something so personal out.

LD: That sharply declined when I quit bartending. And now I actually haven’t had any alcohol in over a year. It definitely has changed my mode of socializing and being in the world. And yeah, I don’t know. I haven’t quite reconciled that yet. I’m still thinking about what that means. There’s definitely a lot of upside to it. But also something that is lost undeniably. I sometimes miss a late night at the bar. I just don’t think I can physically handle it anymore.

AR: My friends and I have started to say we love each other at the end of conversations. What a treasure. Why didn’t we discover this sooner?

LD: I can’t speak for anybody but myself, but I’m lucky, I guess, to have had that for a long time. These friends that I met when I was 13, 14 years old, we always told each other, we loved each other, and we always were very unabashed in our devotion to each other. And I’m really grateful to have had that for so much of my life and to still have it. And I hope to hold onto it.

AR: So for people reading this, how do you create that?

LD: I don’t know because it’s not something I went looking for, I just, I found the right people.

AR: Or, maybe it’s you?

LD: It wasn’t like something I sought out in an intentional way. I met these people, and they became my family. I loved them, and it was important for me to show them that I loved them. If you feel that closeness with somebody, I think a lot of times we get shy or embarrassed, and we don’t want to scare people away.

AR: Yes…

LD: But I think that just going out of your way to do something nice for somebody or sending them a present out of the blue or telling them that you love them or whatever. Being open makes space for them to do that too. Once that’s been established and been said out loud, then it’s easier to live that. Rather than being like I don’t want to text her too much. Maybe she’s busy, or whatever.

AR: I’m obsessed with the final essay in the collection, “On Murder Memoirs.” Why does the book end here, after beginning with Sabina, your cousin who was tragically murdered in her early 20s?

LD: Yeah, I mean, the whole book is about her in a way. I think of all the rest of the essays as overflowing out of that first essay about her: talking about loving her is also talking about loving my friends. Because it’s all this mode of being that I think you were getting at with the last question—this openness and willingness to love in that way. In the essay, “On Murder Memoirs,” my whole point is that it’s not true crime, and that I’m going to write about this person who I love who was killed. I’m going to write about her and about that experience without writing a book about murder. So it’s not a book about murder, it’s a book about love.

AR: At the end, I got that pleasurable rush in my brain, the one you get when you’re reading and suddenly everything comes together. Then I went back to the first chapter, and of course there it was, this line, “This is not a crime story, it’s a love story.” Did you have to go back and rewrite the first chapter after you finished?

LD: No. You know what? Actually, that was already in there. As I was getting to the end of the last essay, I found myself kind of arriving at that same idea that I had started with. I love a full circle moment.

AR: I love that too.

LD: Yeah, it happened organically, but then once I wrote the ending of the last piece and realized that it was intended to kind of direct you back to the beginning and recast the whole book in a way. To revisit a moment, but have it feel completely different.

AR: How does it feel to finish a project that is such an act of love, and to put it out in the world?

LD: All the things. There’s always kind of a scary vulnerability to putting something so personal out. Especially doing it twice in a row in such quick succession. I published my memoir, and I felt really just kind of flayed by the experience. Then it was like, why am I doing this again? It’s a drive, I don’t think it’s a rational or sane thing to do. To publish something so personal. But I feel compelled to explore these things on the page. Once I’ve written them, I’m proud of them, and I can’t help but want to put them out into the world, like a cat dropping a dead mouse in your shoe: there you go.

![[VIDEO] Chloe Bennet in ‘Married by Mistake’ Trailer for Rom-Com Movie [VIDEO] Chloe Bennet in ‘Married by Mistake’ Trailer for Rom-Com Movie](https://tvline.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/married-by-mistake.jpg?w=621)