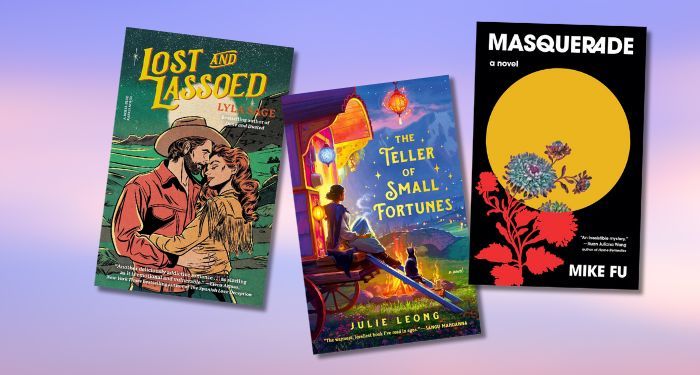

Lauren Elkin’s debut novel Scaffolding traces the parallel lives of two psychoanalysts living in the same Belleville apartment 50 years apart. In 1972, Florence and her new husband, Henry, settle into their new home. But as Florence delves deeper into her intellectual pursuits, she begins to question whether this life truly aligns with her desires. In 2019, Anna inhabits the same space and senses Florence’s lingering presence. While recovering from a breakdown, Anna reckons with her relationship as new and old lovers enter her life. Cerebral and sexy, Elkin’s novel explores the meanings of monogamy, desire, and motherhood.

I spoke with Elkin about the challenges of balancing writing and translating, feminist movements throughout time, and how living in a city informs her writing.

Rose Bialer: How has your experience as a literary translator informed your writing of fiction?

Lauren Elkin: If you’ll forgive the outlandish metaphor, sometimes I feel like being a translator is like being a dressmaker recreating someone else’s garment in new materials. You’re looking at what they made from an incredibly close perspective, working stitch by stitch. I think that’s an incredibly useful habit to be in as a writer—because we’re all readers, first and foremost, we’re all more or less adept at reading as writers and paying attention to how a piece of writing is put together. But as a translator you have no choice but to get right up close.

That’s not always a good thing. Here’s another metaphor: translating is like singing a song someone else wrote, but writing while translating puts you at risk of introducing their phrasing, their dynamics, their musicality into your own work. For instance: I was translating Constance Debré’s Nom at the same time as I was revising Scaffolding, and my god is her stuff catchy, it was SO hard not to get her rhythm stuck in my head. I would find all these comma splices making their way into my work, which is a very French sentence structure but has to be deployed carefully in English, and then I’d have to go back through and tweeze them all out.

That’s not always a good thing. Here’s another metaphor: translating is like singing a song someone else wrote, but writing while translating puts you at risk of introducing their phrasing, their dynamics, their musicality into your own work. For instance: I was translating Constance Debré’s Nom at the same time as I was revising Scaffolding, and my god is her stuff catchy, it was SO hard not to get her rhythm stuck in my head. I would find all these comma splices making their way into my work, which is a very French sentence structure but has to be deployed carefully in English, and then I’d have to go back through and tweeze them all out.

RB: Psychoanalysis figures prominently in Scaffolding. I am curious to know what your relationship is to the subject.

LE: I was ambivalent about psychoanalysis until I read Jacques Lacan in grad school, and then I had one of those lightbulb moments, where I realized what I was reading was speaking right to some of my deepest preoccupations and anxieties—notably his thinking on lack and desire. It was really basic stuff from the Ecrits, the essay about the mirror stage, but it’s where he sets out his notion that we enter subjectivity and language at the moment in our babyhood when we look in the mirror and recognize that we are separate entities to our mothers or primary carers. We lose that feeling of infinite oceanic wholeness at the moment when we gain ourselves—and we spend the rest of our lives trying to fill the void.

LE: I was ambivalent about psychoanalysis until I read Jacques Lacan in grad school, and then I had one of those lightbulb moments, where I realized what I was reading was speaking right to some of my deepest preoccupations and anxieties—notably his thinking on lack and desire. It was really basic stuff from the Ecrits, the essay about the mirror stage, but it’s where he sets out his notion that we enter subjectivity and language at the moment in our babyhood when we look in the mirror and recognize that we are separate entities to our mothers or primary carers. We lose that feeling of infinite oceanic wholeness at the moment when we gain ourselves—and we spend the rest of our lives trying to fill the void.

I wanted to explore these ideas of lack and desire in my writing, and a novel felt like the right place to deploy them! I went on to read as much as I could of Lacan, and found a lot of it pretty hard going, but was encouraged by a friend who is a Lacanian psychoanalyst to just go with it, not to try to read it all or understand it all, but to work with whatever spoke to me.

RB: Both of the time periods in the novel concur with feminist movements in France. Your plot line in 1972 features the “Bobigny Trial,” an event which ultimately helped decriminalize abortion in France. In 2019, two characters are involved in “les colleuses,” a collective that posted messages around Paris protesting violence against women and femicide. I’m curious about any insights you had while exploring these two different, powerful moments in feminist resistance.

LE: It’s funny, I think those two moments crept into the book because I wrote Art Monsters in the last few years before I finished Scaffolding, and that book was so much about collective feminist movements—but I wanted to understand the complicated ways in which feminist movements sometimes leave other feminists behind. The collective is the predominant form for political agitation and progress, no doubt, but collectives are made of individuals, and inevitably leave out some who can’t, for whatever reason, participate as publicly or clear-mindedly as others. What kinds of feminist commitments are possible in the interstices? I think writing these two books has helped me feel a lot more strongly that we all contribute our labor to the cause, we don’t have to do it the same way. One person alone in a room can still be an activist. Looking after your child can be a form of activism.

LE: It’s funny, I think those two moments crept into the book because I wrote Art Monsters in the last few years before I finished Scaffolding, and that book was so much about collective feminist movements—but I wanted to understand the complicated ways in which feminist movements sometimes leave other feminists behind. The collective is the predominant form for political agitation and progress, no doubt, but collectives are made of individuals, and inevitably leave out some who can’t, for whatever reason, participate as publicly or clear-mindedly as others. What kinds of feminist commitments are possible in the interstices? I think writing these two books has helped me feel a lot more strongly that we all contribute our labor to the cause, we don’t have to do it the same way. One person alone in a room can still be an activist. Looking after your child can be a form of activism.

RB: You write that you worked on Scaffolding between 2007 and 2023. The novel includes certain details that occurred during this time such as the emergence of “les colleuses” and the pandemic. Besides these larger elements in the plot, is there anything else that happened in the world—or maybe your own life—that redirected the course of the book?

LE: Oh sure—over the course of those years I went from ages 29 to 45! I got married and divorced and repartnered, I had miscarriages, an abortion, and then a child—all of these things fed the book and helped me imagine myself into the world I had created, in a way I simply couldn’t have done when I was in my twenties. And yes, in terms of what was happening on the world stage, there were the terrorist attacks in Paris in 2015, which really fundamentally shifted the way I thought of the city and my relationship to other people in it. I think Scaffolding after 2015 was a book that was much more interested in Anna being in the context of the city, as opposed to just shutting herself away from it, so that enabled me to write the second half of the third section. The fire at Notre Dame as well, the gilets jaunes protests, the strikes—these were such important moments in Paris, and they just rooted the story in its particular time and place, and shaped the way Anna moves through the city, what she thinks about, how she feels about it and her place within it.

RB: Your novel has wonderful moments of observing the city. As your previous works like Flâneuse and No. 91/92 are in different ways about urban life, how does the fictional world of Scaffolding writing connect to your earlier nonfiction work?

RB: Your novel has wonderful moments of observing the city. As your previous works like Flâneuse and No. 91/92 are in different ways about urban life, how does the fictional world of Scaffolding writing connect to your earlier nonfiction work?

LE: When I began writing this book, I hadn’t yet written Flâneuse, but that book set me on this path of relating to the city through writing, literature, and art, and I could not have predicted how that would seep into this novel, but it did! For such a long time I tried to understand how my “creative” and “critical” work could come together, and the answer turned out to be by allowing my writing to be guided by the city. If No 91/92 was a kind of Flâneuse without the research, Scaffolding is that book transformed into fiction.

RB: At the end of the novel, you include the five addresses (six if you include your residency at Shakespeare & Company) where you worked on writing Scaffolding. In your case, and in the case of Anna, what does the place where you inhabit mean for thinking and work that you create there?

LE: Just as the novel moved forward in time from 2007 to 2019, where I finally set it in order to coincide with the colleuses, the setting moved with me from the 5th to Belleville, which I finally decided on as the setting for the book in the mid 2010s or so, when I first moved there. It’s such a rich neighborhood, in people, textures, history—reading about Belleville, its geological structure, the springs running beneath its streets, its precariousness due to having been hollowed out in so many places, quarried for gypsum, its revolutionary past, its vibrant but edgy present-day—it had just the energy I needed for these people who were struggling with memory and desire and habitation.

In my own case, all I can say is that I find Paris, and Belleville in particular, to be indispensable for my writing, even when that writing doesn’t really have anything to do with Paris. Paris made me a writer—I trained myself by sitting in cafes and writing every day, starting around the age of 20. Now I live in London and we don’t have cafés the same way, but my daily practice is still with me.