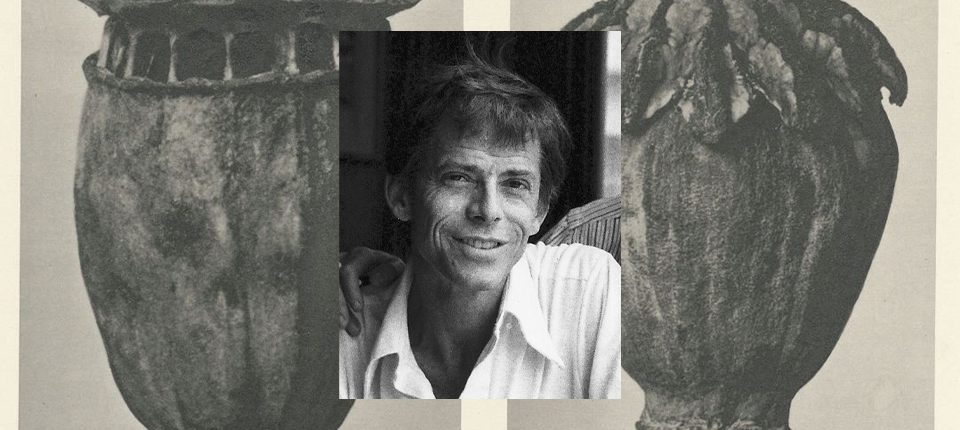

In Kiley Reid’s novels, there are no real heroes or villains, just people navigating the considerable pitfalls of life and slipping up along the way. Bad judgment, yes. Bad people? That’s a little simplistic for Reid.

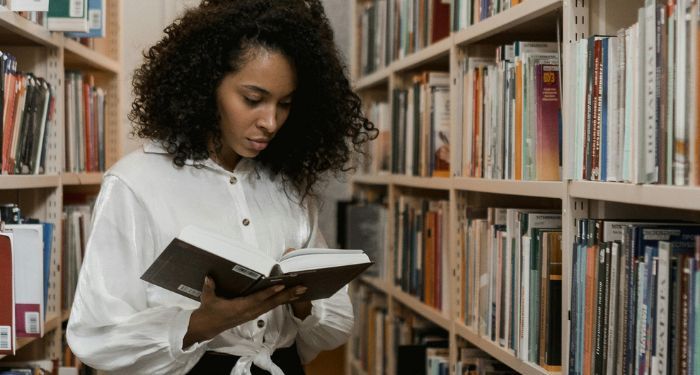

“For the most part, I think people are trying,” Reid says via Zoom from Ann Arbor, Mich., where she’s lived since she began teaching writing at the University of Michigan in 2022. “Sometimes their attempts make them falter a lot, and I like to replicate that with my characters.”

Reid says the research she did for her new novel, Come and Get It, showed people in all of their fullness. “One moment they would say something completely charming, and the next moment they would say something extremely classist,” she explains. “And for me to only put one side of that in every character feels a bit irresponsible.”

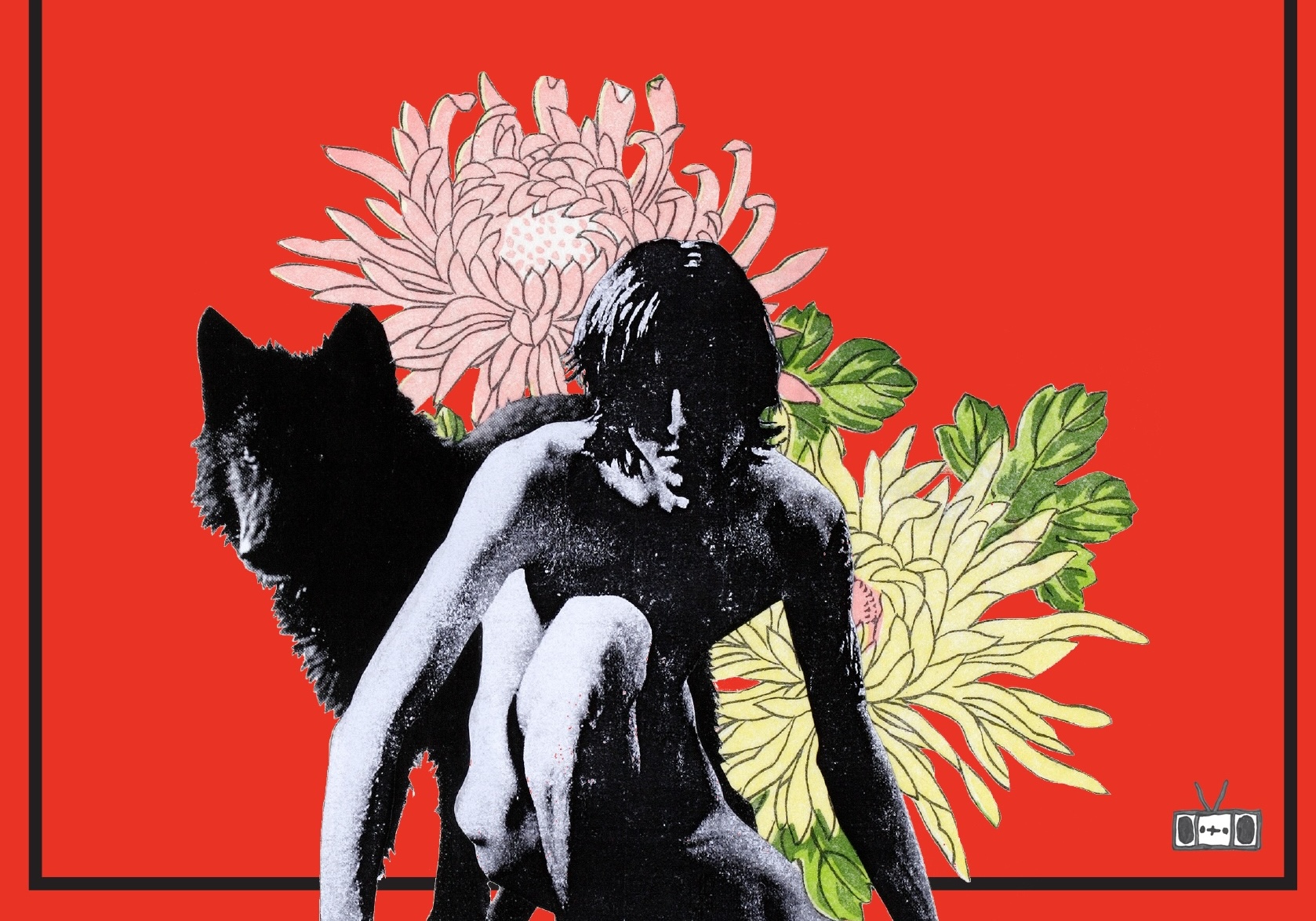

For her debut novel, Such a Fun Age, which was a bestseller and was longlisted for the 2020 Booker Prize, Reid drew on her experience as a nanny to show the drama that ensues when a young Black woman babysits the two daughters of a wealthy white mother and is harassed by security at an upscale grocery store while watching one of the girls. Come and Get It is set at the University of Arkansas and depicts a group of women whose lives intersect in a narrative about bad decisions, shaky ethics, and desire, both material and sexual.

For her debut novel, Such a Fun Age, which was a bestseller and was longlisted for the 2020 Booker Prize, Reid drew on her experience as a nanny to show the drama that ensues when a young Black woman babysits the two daughters of a wealthy white mother and is harassed by security at an upscale grocery store while watching one of the girls. Come and Get It is set at the University of Arkansas and depicts a group of women whose lives intersect in a narrative about bad decisions, shaky ethics, and desire, both material and sexual.

Agatha, a white journalist and professor, arrives in Fayetteville to teach writing and work on a book about weddings. She becomes fascinated by a group of undergraduates living in a dorm, and by their relationship to money—how they get it, how they spend it, and how easily they take it for granted. Meanwhile, Millie, the dorm’s Black RA, grows infatuated with Agatha, who finds a way to use their relationship to her professional advantage as she pivots from her initial project to a series of online student profiles, for which Millie helps her gather information in a way that bends the rules of journalism.

Reid’s strengths as a novelist include an ear for dialogue and an instinct for plotting. There’s also a focus on work via the things her richly developed but deeply flawed characters do to make ends meet and find meaning.

“In a Kiley Reid book, you always know how much rent the character pays,” says Sally Kim, senior v-p and publisher at Putnam and Reid’s editor for both novels. “You know the last time they washed their car, and how long their hair is, and how much they sold their house for. She’s very specific about these details, because for her, that’s where the emotional details come out.”

Issues of class are never far from the action in Come and Get It. Some of the young women Agatha interviews are spoiled rotten without knowing it, and are convinced they’re self-sufficient even as they rely on parents for most of their funds. Other characters live paycheck to paycheck. Millie, who works at the dorm and at a coffee shop, socks away money for a down payment on a modest home. Agatha is getting over a relationship with a dancer named Robin, who has a habit of sponging cash. These financial battles give way to emotional conflict, and in some cases propel the narrative.

For Reid, who grew up in Tucson, Ariz., studied drama at Marymount Manhattan College, and published Such a Fun Age as a student at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, there are direct connections between having cash at hand and being able to write for a living. She earned an MFA from one of the most prestigious writing programs in the world, but she knows that’s not an option for everyone who has talent.

“I think it’s a huge detriment to literature that the MFA programs are the most consistent pathways to publication,” she says. “Most people going to MFA programs are coming from backgrounds that allow them to spend sometimes $50–$100 per application, and some of them are paying to go to school, where other people couldn’t afford to do that.”

Reid is grateful for her Iowa experience; she just thinks the system could use some fixing. “On one hand, I am very happy that programs exist for people to concentrate on writing,” she says. “I know how beneficial that can be. On the other hand, I fear that the MFA system is just available to the same type of writer from the same type of background, and therefore we can get the same types of stories over and over again. And I, for one, would love to see new literature.”

Another important theme in Reid’s fiction, running parallel to that of class, is race. However, this isn’t something the author addresses in obvious ways—and she has little interest in making it her only subject.

“I like reading books about race,” she says. “But Black people are not always thinking about being Black. They’re thinking about their rent and their crushes and their insecurities and all of those human things. It comes in and it goes out in my work, and I feel like that’s pretty realistic. It reminds me of offices that I’ve worked at where most of the time it’s okay, and then it’ll come in and you’re reminded of it again. I feel like that’s pretty comparable to real life.”

And real life is where Reid’s characters tend to live, amid all their messiness and dreams. This makes it easy for readers to see themselves in the author’s work. It’s also one reason they keep reading.

“All of these characters are going to do what they’re going to do, and it’s almost like they need to justify their bad behavior,” Kim says. “I think we all can recognize ourselves in that, whether you identify with the students or the professor or the RA, you can relate to the different stages of life that all these characters are in and how they’re trying to become themselves.”

The profile was produced in partnership with Publishers Weekly.