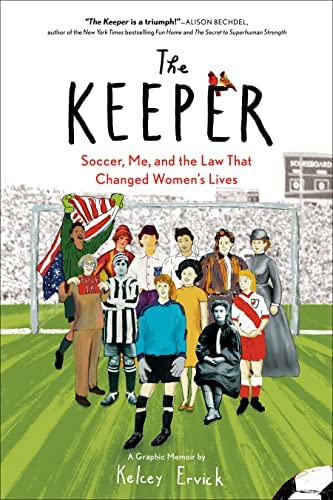

In one of my favorite pages of The Keeper, Kelcey Ervick‘s graphic memoir about her time as a goalie in the early days of Title IX, Ervick is, at this point, no longer a teenage soccer player. Time has passed, and she’s now a wife and a mother trying to take herself seriously as a writer and artist. On this page, Ervick has drawn herself as a loopy contour of lines, writing at her computer—you can see right through her body to the furious scribble of her hands working her keyboard. Her figure is transparent, but effervescent; we’re witnessing her in a moment of transcendence. “I was getting angry,” she writes at the top of her page. “I was finding my voice.”

I love this illustration for how it captures that moment of being so deeply inside yourself that you begin to disappear; what a relief for the identity that dictates so many of one’s experiences to recede just a little. Title IX, the civil rights law that prohibited sex-based discrimination in education programs receiving federal assistance, and which just celebrated its fiftieth anniversary, led to a sharp rise of women in sports. Ervick, who played on a top soccer team in the 1980s, was one of those athletes whose participation in high school and collegiate soccer was made newly possible. “My teammates and I didn’t know of any of this,” Ervick writes. “But [Title IX] shaped our entire lives.”

My favorite page also perfectly exemplifies what cartoonist Alison Bechdel has called Ervick’s “loose and exuberant” style. Ervick’s hand moves flawlessly between different visual mediums and styles—gouache, watercolor, collage, newspaper print, photographs. Sometimes she paints people in great detail and other times she depicts them as stick figures rushing down the field, as if, in their athleticism, they’ve shed all the particulars of their bodies. She also flits between different modes of nonfiction, weaving memoir with a history of women’s soccer, literary analysis, and culture writing. It is an exhilarating book to read and to look at. Ervick refuses to stay within the lines of any category, any image, any self. By the time one finishes The Keeper, one realizes that the title refers to so much more than just a goalkeeper—Ervick has proven herself to be a keeper of archives, of memories, and of undertold histories.

I spoke with Ervick about the challenges and rewards of turning to graphic narrative after three other books of nonfiction and fiction, the relationship between athleticism and art, and balancing research and the personal.

Lena Moses-Schmitt: You’ve written three previous books—a book of short stories, a novella, and a genre-bending work of biographical collage)—but this is your first book of full-on graphic narrative. What was it about this story that made you want to transition into fully graphic nonfiction? What was your learning curve like, if you had one?

Kelcey Ervick: I think I’ve basically been scheming to make a book of graphic nonfiction since I first read Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home and Maira Kalman‘s Principles of Uncertainty nearly 15 years ago, but I knew I had a long way to go. For a while with this book, I thought I had an essay collection developing. I was writing individual essays about the different threads: being a soccer-player-turned-soccer-mom, being an athlete-turned-artist, experiencing sexism in sports and literature. Separately, I was making comics, primarily about women artists, athletes, and activists throughout history. At some point I realized I could bring them together—the personal narratives, the history, and the comics—and, more importantly, that I was ready to do it.

Kelcey Ervick: I think I’ve basically been scheming to make a book of graphic nonfiction since I first read Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home and Maira Kalman‘s Principles of Uncertainty nearly 15 years ago, but I knew I had a long way to go. For a while with this book, I thought I had an essay collection developing. I was writing individual essays about the different threads: being a soccer-player-turned-soccer-mom, being an athlete-turned-artist, experiencing sexism in sports and literature. Separately, I was making comics, primarily about women artists, athletes, and activists throughout history. At some point I realized I could bring them together—the personal narratives, the history, and the comics—and, more importantly, that I was ready to do it.

I describe myself as a writer who started drawing, and when I first began working with visual storytelling, I definitely had a writer’s learning curve. As I floundered with some early attempts at comics, I worried that I was over-pruning my sentences and merely decorating them with an image. I also felt like I couldn’t get any narrative momentum because I was laboring over a drawing of lettuce leaf on my character’s salad fork.

I feel like I’ve put myself through a second PhD program trying to learn how to make graphic narratives: I’ve spent years taking comics workshops (at Tin House, Sequential Artists Workshop, the Center for Cartoon Studies, etcetera), I teach graphic narratives in my own classes, I practice through daily drawing, and I am even co-editing a book with Tom Hart on making graphic literature! (The Rose Metal Press Field Guide to Graphic Literature is coming in 2023.)

LMS: Yes! I can totally relate to the worry that I’ll slip into drawing images that might simply decorate or even just illustrate what I’m already saying with words—for me I think that’s a risk that comes along with losing energy, or when I rely primarily on text, rather than also letting myself daydream visually. How did you keep your stamina up for both words and images throughout such a long project? Did you tend to “think” in text first or in images?

KE: I love that phrase, “letting myself daydream visually”! In terms of stamina, one thing that was both a blessing and a curse was my fairly tight deadline. I quite literally didn’t have time to separate the tasks of writing and drawing as I imagined and drafted. I put in what felt like a zillion hours making the book, but instead of spreading it out over several years, as would have been my preference, I compressed most of the work into one year. This allowed me to keep better track of the overall arc and story than if I’d stopped and started with long gaps in between.

At this point, I’m not even sure I think so much in text or image as through text and image. Many writers quote the familiar line (I’ve seen it attributed to Didion, Faulkner, and O’Connor) that says something like, “I write to find out what I think.” This has always been true for me: I do my thinking through the act of writing. And now, after a lot of practice and retraining my brain, I can say that I think through both text and image: I figure out what I want to say through the act of doing it. To paraphrase Lynda Barry: “The pen knows what to do.” When in doubt, I start moving my pen and wait to see what words and images emerge.

LMS: What was your outlining process like with this book?

KE: I love thinking structurally about my books and stories. What will be the overall shape? How will I juggle the narrative threads, the movement in time? Will there be chapters? Will they have titles? I make a bunch of notes and then I test and change them as I go. For example, in my book proposal, I said there would be three sections to the book: “Girlhood,” “Womanhood,” and “Sisterhood.” I didn’t think it would have individual chapters. But as I drafted the book, chapters emerged—separated by individual teams I’d played on and life events—and the three larger sections fell away, though the book still follows their implied arc.

Sometimes finding the right title of a chapter helped me find its focus. For a long time in the drafting stages, the only title I had for my chapter about my high school years was, well, “High School.” As I added more lines from my high school diaries along with the notebooks I exchanged with my friend, I landed on its current title, taken from the title of a Joan Didion essay “On Keeping a Notebook.” The new title gave more weight to the themes of writing and friendship—and echoed the idea of keeping/goalkeeping.

LMS: You use a number of different graphic mediums—some pages are digitally illustrated, others feature watercolor drawings, some pages are collaged, and there are also full spreads of gouache paintings. The way you balanced all of them felt very expansive and exciting to me. How did you decide which style to use for which images, and what was it like to merge these different mediums together?

KE: I came to visual storytelling not so much through traditional comics as through other forms of image-text art like calligraphy, collage, and mixed-media art, all of which shaped my loose, expressive style. I’m always exploring new mediums, and I usually let the content inform the style. In The Keeper, for example, when I wrote about the “lady footballers” of the Victorian era, I found myself using a deeper palette (maroons and darker greens) than when I was writing about my 1980s soccer team (with our red uniforms and brighter green fields). Or I included a gouache painting to add a bit of texture or contrast to a sequence.

It felt somewhat risky to combine a variety of mediums in one book, but all I had to do was look to some of my favorite books as an example that it could be done: Maira Kalman’s books are dominated by her gouache paintings but also include her photography and embroidery; Nora Krug’s Belonging alternates sequential art scenes with found images, collage, and illustration; and Roz Chast’s Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant? has a thoughtful array of cartoon sequences, snapshots of her parents’ apartment, and tenderly drawn portraits of her dying mother.

It felt somewhat risky to combine a variety of mediums in one book, but all I had to do was look to some of my favorite books as an example that it could be done: Maira Kalman’s books are dominated by her gouache paintings but also include her photography and embroidery; Nora Krug’s Belonging alternates sequential art scenes with found images, collage, and illustration; and Roz Chast’s Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant? has a thoughtful array of cartoon sequences, snapshots of her parents’ apartment, and tenderly drawn portraits of her dying mother.

LMS: I also love how your combination of different mediums speaks to the collage of different threads here, as well as the hybrid of selves you’re exploring—goalkeeper, writer, artist, mother. What were some of your biggest challenges (or excitements) you faced writing a graphic memoir which wove your personal story with history and literature? I’d especially love for you to talk about the process of drawing parts of the book that aren’t active “scenes” per se—where one character is talking to another—but where you draw on archival and historical research, or where you have to illustrate “thinking” and “reflecting.” Those are the parts of graphic work I often find the most difficult.

KE: I love archival materials and find them aesthetically beautiful, whether it’s my own memorabilia or photos and documents from distant times and places. It’s just a joy to draw them and pair them with historical context or my own musings. Beyond that, when I interpret a black-and-white photo with bold color or with stylized lines, it’s a way, I hope, of making the image and text interaction more active and alive. One of my challenges in blending my personal story with literature (such as Vladimir Nabokov’s writing about his love of playing goalie) or with the fascinating discoveries I was making about women’s soccer history going back to the late 1800s was that I would get so interested in the research that I ran the risk of losing the story. I know there’s a lot of history and literature woven in the book, but believe me, there’s a lot I cut!

LMS: What are some things that surprised you most, as you were doing research for this book?

KE: So much surprised me—that’s the joy of research! I was surprised to learn that 100 years ago during WWI in England, there were women playing soccer and drawing crowds of thousands of people. It was so popular that in 1921, the British Football Association literally banned women from play on the grounds that the sport was “quite unsuitable for females.” That ban lasted for 50 years! I was surprised—though maybe I shouldn’t have been—that the issues women athletes face today are exactly the same ones they faced a century ago: public debates about their bodies, looks, and clothes; critiques of their play; concerns about their sexuality and gender; inequities in facilities and compensation; etcetera, etcetera, forever. I was also surprised to learn how much literature there is about soccer and especially about goalkeeping, mostly by men and mostly outside of the U.S. like Nabokov and Albert Camus and Eduardo Galeano. And I was surprised how painful it was to read my high school diaries.

LMS: In one chapter, you write about doing The Artist’s Way as an adult, trying to rediscover who you are, now that you no longer play soccer—“At the time,” you write, “I believed that a person could be an athlete or an artist, but not both.” When The Artist’s Way prompts you to identify your enemies to creative growth, you write: “Sports!” But as the book demonstrates, it’s of course not so simple—can you talk a bit about any connections you see between athleticism and writing/drawing, and how being an athlete enabled you to be a writer who draws?

LMS: In one chapter, you write about doing The Artist’s Way as an adult, trying to rediscover who you are, now that you no longer play soccer—“At the time,” you write, “I believed that a person could be an athlete or an artist, but not both.” When The Artist’s Way prompts you to identify your enemies to creative growth, you write: “Sports!” But as the book demonstrates, it’s of course not so simple—can you talk a bit about any connections you see between athleticism and writing/drawing, and how being an athlete enabled you to be a writer who draws?

KE: Yes, I was surprisingly wrong when I thought that sports were the enemy. In fact, The Artist’s Way has a section on the “Zen of Sports,” where Julia Cameron stresses the importance of physical movement in the creative process: “We need to move out of the head and into the body.” The poet and former basketball player Natalie Diaz writes elegantly about the body as the locus for both poetry and basketball: “I have a crafted and earned intimacy with my body. I know and trust it differently than a nonathlete can. It’s the way I make sense of the world, a lover, a book, the earth.” I recently got to attend a reading by Hanif Abdurraqib, and I also love how fluidly and frequently he references his experiences as an athlete when talking about his life as a writer. Often it’s in connection with a sense of competition or with the ability to push himself through a challenge.

All of these ideas resonate with me deeply: We feel art and literature in our bodies, whether reading or creating it. I know that I developed a healthy sense of competition and drive from sports, and I also learned how to deal with disappointment. When you play game after game after game, you win and you lose, and as a goalkeeper you get scored on! You have to train yourself psychologically—and are trained by coaches as well—to keep going. I definitely applied this discipline to my life as a writer.