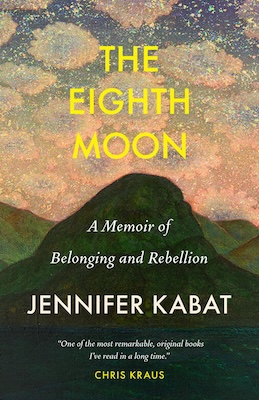

The Eighth Moon: A Memoir of Belonging and Rebellion is a deep consideration of land, ownership, and civil society tracking the histories of an author and area in upstate New York. Jennifer Kabat studies time in a continuous present, watching the past bleed onto now. That blood is from the wounds of land theft and the confusing heartbreaks of our democracy. Her reckonings find echoes between financial crises of the late 1830s and the early 2000s; between the Anti-Rent Wars of the 1840s and the anti-government rebels of 2021; and between generations of her family, sharing a deep commitment to cooperatives.

The book revolves around narrations of one of America’s first populist uprisings, the Anti-Rent Wars, where tenant farmers rose up against feudal landlords. The region still had a Dutch property system, unchanged by British control, the American revolution, nor the founding of New York State. During a drought and a long, punishing recession, gangs wore leather masks and calico dresses and fought authorities who claimed payment on behalf of the ruling families.

Late in April, I drove over small roads through thinly populated places, eager to walk the paths and forests that hold Jennifer Kabat’s imagination. The sky was full of portentous clouds, and the fields that quilt the soft, worn-down mountains were muddy, unplanted. I was thick with her book and wondering how to seed its central idea in the general population. Shouldn’t we all be digging for clues of how to be responsible toward each other in contemporary times?

Amy Halloran: You wrote that you’ve always had problems with tenses, and time slides through you, and you through it in the book. Talk to me about time and chronology, and how you use them.

Jennifer Kabat: I remember being in my MFA program and someone saying, you can write in the first person, but you can never write in the first person present, as a kind of dictum. I found that really strange even if sometimes it’s true.

If you’re writing in the past tense, the reader knows how to place themselves around the action because the teller has come out of that action and has a different point of view, so there’s a reason to tell that story. So, readers feel a sense of security with the first-person past tense because they feel like they understand what’s happening. We were told not to ever do first-person present because it’s going to make your reader feel uncomfortable. I remember wondering, why should somebody be comfortable in a text?

The idea of somebody feeling safe is part of the idea that plot leads us to a new and better place, where plot and progress are kind of interchangeable. A lot of Western literature, the novel, or the memoir or whatever, has that as a structure or a fantasy of the world. I was like, well, what if we make the reader uncomfortable? What if we present them with facts?

And then if you do deep research, you kind of feel like that person or history is alive with you all the time. The way they kind of vibrate into your presence or the present tense starts to feel permeable. We live on this land in the Western Catskills and there’s this old stone foundation up there and at some point—I mean like, I’m a Pisces so I’m pretty porous and can feel kind of translucent with the world around me. Living with this foundation I feel like I live here with the people who had been there? How can you reflect that experience in writing other than if the past could be in the present tense? If the past can be in the present tense, it’s also like saying the idea of plot getting us to a new and better place is also a fantasy.

AH: How did you come to handling time in this book?

We were told not to ever do first-person present because it’s going to make your reader feel uncomfortable. I remember wondering, why should somebody be comfortable in a text?

JK: Well, I was writing a lot in the past tense, and it felt so uncomfortable. I was trying to write this stuff where it was all joined together and there were segues between the action. “Then a week passed. And this happened,” you know what I mean? Where time was continuous versus discontinuous.

I was writing a kind of memoir about my parents and modernism and all these things that I’m really interested in, but it was way too linear, and so it was kind of stifled. I was glad this book didn’t sell, and I realized I should write a book against the expectations of what the market wanted.

AH: I’m curious about how you lace together multiple experiences, people around here from Indigenous times through the Rent War’s time through contemporary rebels. How did those come together, and how did it feel as you were trying to make them meet?

JK: Partly, I started researching this piece of land that we couldn’t afford to build this house on, where we could only have a tent. I was writing these essays that were kind of grounded in place, that started with a project in Bristol in the U.K., for this contemporary art museum, Arnolfini. I became really interested in the ghosts of a place. And for me, those ghosts could be a piece of gum on the pavement, all the things that we overlook. Bristol was one of the capitals of the slave trade in the UK. The streets were basically paved with enslavement, and so I was interested in what are the values held in a place.

Here, there are ruins on this land, and I couldn’t figure out anything about them. I wanted to understand who had lived here and what the conditions of their life had been. Research led me to realize a tenant farmer dies in absolute poverty (in these ruins) at the moment the uprising is starting to happen—well where’s that going to take me?

AH: Can you talk about the book as a way of dealing with being a white person, a person of privilege on native ground?

JK: Yes, I’m on Indigenous land, but also, I’m thinking about being a white person of privilege in a place in which a large portion of the population might earn at or just above the poverty level. All artwork is created in a context, and I’m socialist, and I’m kind of a Marxist in that the material conditions of our world create what is allowed to exist in that world. If I’m writing a book about living here, it seems like the material conditions under which I get to live here are part of the question. And if you believe all time to be alive, that includes what does it mean to live on Indigenous land, what are those histories and how do all those histories exist?

AH: Do you feel like you got a sense of peace by acknowledging all of these layers?

We’re on a precipice and I want people to question the current state of American capitalism.

JK: I don’t know if that’s possible. This book is part of a diptych. So, there’s a second book. This first book has my mom as a subtheme and the second book is kind of my dad. And in a way they are both reckoning with the Indigenous histories here and not seeing them as over, but continuous in this moment. Both books think about this, the first about the Munsee, and the second the Mohawks. I stumble over this. They are both reckoning with the Indigenous histories here. Like the first one really thinks about the Muncie and the second one really thinks about the Mohawks.

The people who were taking native lands, their socialist fervor did not extend to seeing who was on the land. This is a tradition I come from. I really identify in a very agrarian, socialist way. But that tradition is not without harms. I don’t know what to do with that and so and in the second book, those harms feel much more visceral to me. And I don’t actually think there is a fix. Having something to grapple with, not having answers—not having answers to me that feels necessary.

AH: Do you think a reader could take your self-scrutiny and apply it to their own life and place?

JK: Maybe. I mean, I hope so. And the second book, which is twinned with the first, is left even more unfinished. And the unfinished is really my intention. There is some closure that I have, but it is not closure that I want to extend because I think it’s actually more profound to live in a place of rupture with some of this stuff. I’m aware that I’m talking about something very abstract.

I don’t think there’s anything remarkable in this book. I think that everybody could look at their place in a way with the same kind of questions and the same intensity. But I didn’t set out with an agenda to show a way for people to be with themselves. It was more like this is how I live in this place.

AH: An itch to understand yourself and your place.

JK: Yes, and my family and its place in this place.

AH: Do you feel like you’ve wrestled with these questions of belonging and rebellion sufficiently for the moment?

JK: I don’t know. Our country is going through a huge period of uprising. And I don’t feel like it’s finished.

I feel like people need to think about the larger context of U.S. democracy. There are things that are not fully functional in U.S. democracy, like the Electoral College, but it really supports rural America. The Anti-Rent moment looks really like the January 6th moment. This is not to say I think people should be attacking the capital, but if we could look at those moments with equal generosity, the motivations behind both of those things are similar. There were tenant farmers who were living in perpetual peonage to a landlord, but many people today in America, particularly in rural places, are living in stagnating economies. And those rural economies also don’t exist without federal funding and subsidies. There’s a real disconnect happening now in any discussion of what that white rage means or looks like, and the thing that happened in the 1840s was that these poor white farmers really linked their plight to everybody else’s. They thought about abolition. They thought about the immigrant crisis, like it was a moment where there was a lot of immigration from Northern Europe. And the Irish and the Germans were castigated in the ways that we might castigate somebody with Black or Brown skin trying to come to this country now. And yet they tied their plights to them. People were working jobs in dire conditions, and they felt like what they were doing here connected to all these people to the enslaved people in the South. And that is a really radical position.

However, they did not see Indigeneity. They had huge blind spots. But the thing I find fascinating is you know, here we have this white uprising today but nobody is tying their needs to anybody else’s. The conditions under which people are being screwed over by dead end jobs in this country or wealthy people getting wealthier, or health care which is exorbitantly expensive and has some really bad outcomes, and the fact that life expectancy is now going down in this country. All that stuff is true across the urban, rural divide and few people linking that up and making a case for that.

AH: Are you excited about the book allowing you to have more conversations about the disconnects?

JK: I guess I’m also terrified. I live in this community, and I write really intimately about it. And I’m scared of how people will see it. Can I write about marriage, which I think is a tool of capitalism? What are my dear neighbors who are very full of faith going to think? Are they going to be like, what’s wrong with you?

I come from a pretty leftist, capitalist questioning background. And by laying those material conditions out there on the page, it’s also a point where people might question me.

I’m really interested in what the dream of the U.S. represents. You know, I grew up in a family that was really patriotic. And I don’t think being patriotic and questioning should be at odds. So, if we’re not going to have those conversations now, when?

AH: Right. We’re on a precipice.

JK: We’re on a precipice and I want people to question the current state of American capitalism. I think it is making the country way more undemocratic. You get uprisings in moments of massive inequality. And the tax structure is not serving everybody. I would love this book to be a way to ask those questions, to get people to be like, why aren’t we organizing?

The book is kind of an experimental book, but I want it to matter here as much as elsewhere. I want the book to exist within this community as its own complete thing.