I was a single parent when I got married on my lunch break. Taking a day off from my unruly job in foster care wasn’t feasible, plus I was pregnant and my health insurance was crap—it didn’t cover office visits or emergencies (or, ahem, birth control). So, after a quick exchange of vows at the courthouse, my new spouse went home alone and did laundry, and I went back to the office. Soon after, I scored my dream job as a school counselor—a small miracle given that I didn’t possess any of the required professional qualifications—but it didn’t last long. Before I even fully returned to work after my maternity leave, I quit because my employer said I wouldn’t be allowed to pump or nurse the day of kindergarten screenings. I went from being a single, working parent to a married stay-at-home parent in less than a year.

All of this was ages ago now, and my life is so different, it’s easy to forget the mounting frustrations that once consumed me. But reading Yamada Murasaki’s Talk to My Back forced me to remember.

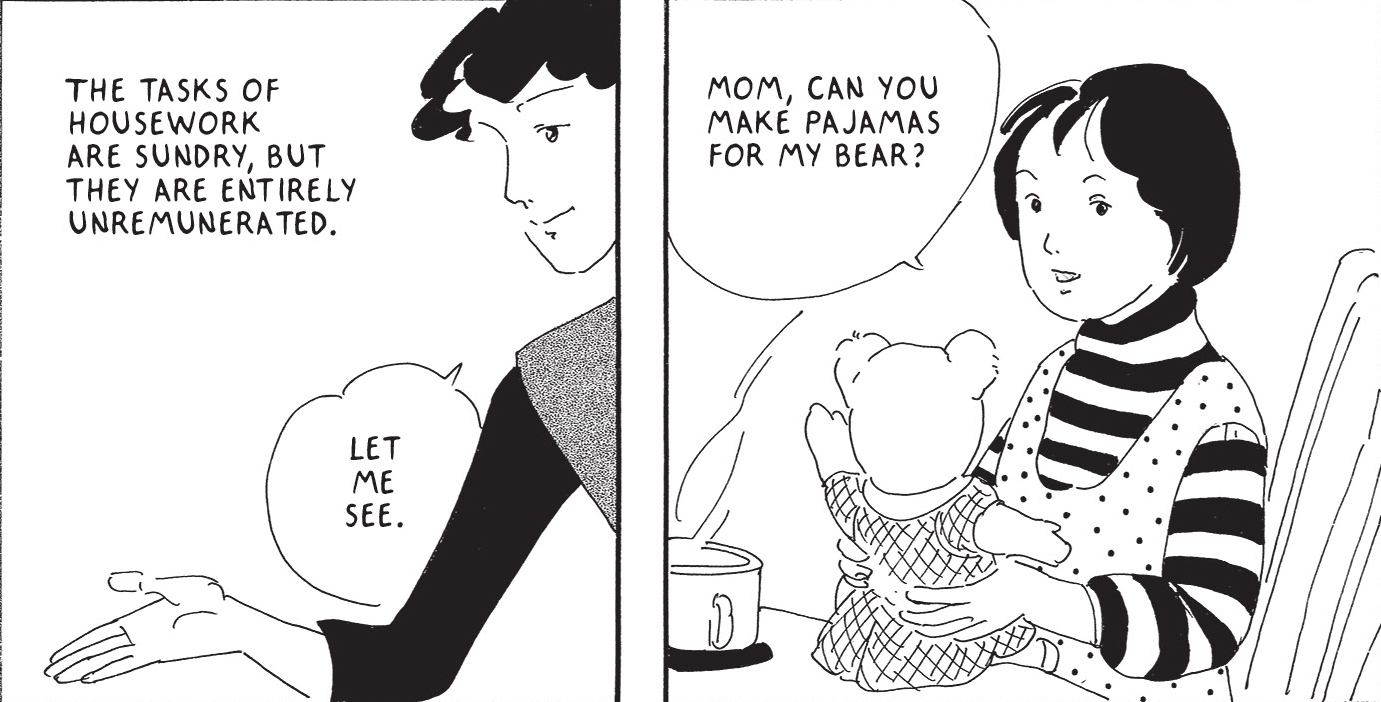

The comics in Talk to My Back, serialized from 1981 to 1984 in the Japanese magazine Garo, feature a mother caring for her children and thankless husband, highlighting the aggravations of domestic life. Thirty years later, the first English edition is available from Drawn & Quarterly, translated by Eisner recipient Ryan Holmberg. To fully appreciate Murasaki’s work, you also need an understanding of its historical framework, but lucky for readers, the book includes an in-depth essay by Holmberg, which offers some cultural context, basic history of alt-manga, and an overview of Murasaki’s life (1948-2009).

Murasaki was, quite simply, a badass. In addition to her accomplishments within manga, she was the vocalist in a folk band, wrote poetry, and ran for political office. While “she’s rarely named among the leaders of ‘women’s manga’,” Holmberg describes her pioneering role as one of the first cartoonists in Japan who dealt with “the difficulties of womanhood in a realistic, critical, and sustained way, and outside the thematic and pictorial conventions of shōjo manga and its preference for fantasy.” And yet, he notes, she’s not often mentioned in literature about gender and women’s issues within Japanese pop culture, “even in Japan, where every serious scholar and fan knows her work.”

Like many artists, Murasaki’s work was shaped by her personal life. When she was twenty-four, she married one of the members of the folk band she’d sung in as a teenager. In a 1985 interview she said, “I really had big dreams about marriage. I was raised in a household without a father, so I was super jealous of normal families. Cleaning the house, doing the laundry, washing the dishes, and so on while living in a proper house—I couldn’t think of a better life. But once you get to doing it, then you realize how unnatural it is.”

As a single parent, I had harbored my own unrealistic ideas about marriage and domestic life. I shuffled to government offices and free clinics with staff who’d mumble about “freeloaders.” Some thought I was married, others assumed I was straight, everyone writing their own narratives about me as I juggled solo parenting, waitressing, and, eventually, graduate school. Before getting pregnant I’d been pursuing a degree in art therapy but dropped out of the program to attend a school closer to my support system, where I instead studied English and reading instruction. And yet somehow, I’d landed a counseling job—more than that, by incorporating art into sessions, I was essentially working as a (woefully uncredentialed and untrained) art therapist. My decision to quit was as impulsive as marrying on my lunch break. I didn’t discuss it with my spouse or talk to HR, didn’t look into my legal rights. Why? Because I knew how to live on very little money and, like Murasaki, romanticized the normalness of days spent cleaning and caring for babies.

The unnaturalness of domestic life is explored in Talk to My Back, which Murasaki created as a single mother after her first marriage ended. We see the inherent loneliness Chiharu Yamakawa, the protagonist, feels as she cares for her husband and two daughters, irritated by the unequal division of domestic labor and responsibility in parenting. But at its core, the work centers Chiharu’s self-worth and her relationship with herself. She wrestles with questions of who she is, independent of her roles within the home. Murasaki resists easy answers, playing with visual effects to complicate how Chiharu appears—in panels we often see her without a face, or with her features only half-drawn: a shadow of herself. It’s apparent in these small details what a master of the form Murasaki was. She understood how space and omission—of both details and words—could be leveraged in art and writing. She wielded these tools with sharp accuracy, and the result is a biting commentary on domesticity.

Holmberg explains that it was rare in Murasaki’s time for manga to dive into this domestic sphere. Talk to My Back was often described as “shufu manga,” a term that translates as “female head of household,” but that evokes images of “professional housewives.” He further clarifies that while Murasaki proudly self-identified as shufu, she “squirmed” when others labeled her as such. Holmberg also notes that at the time Talk to My Back was published, the labor demographics in Japan were quickly changing, with almost half of married women employed by the mid 1980s, and professional housewifery was “undergoing a new round of interrogation, under the pressure of radical feminist movements.” American readers—especially now, thirty years after the series debuted—may find the work anachronistic. And yet, the protagonist’s frustrations are relatable. Or, at least, I found them relatable, though it’s been nearly two decades since my life shared any similarities to Chiharu’s.

American readers—especially now, thirty years after the series debuted—may find the work anachronistic.

The collection opens with “Lonely Cinderella,” which takes place after Chiharu’s kids go to sleep. After briefly reveling in the night being hers, the mood shifts to a despondency many will find recognizable: “The TV is on, but I don’t watch it . . . I have a book open, but I don’t read it . . . Eventually I come to, and realize that I’m hardly here.” She doesn’t know what to do, then the clock chimes and the spell is broken. Time to wash dishes. The cartoon slips into the fantastical: a shadowy figure lurks behind her. The scare is interrupted by a call from her husband—he won’t be coming home after all. She hangs up the phone and makes peace with the ghostly figure, acknowledging that some days are “intolerably” lonely. The end panel is of Chiharu standing alone, embraced by a phantom partner. The image somehow manages to be both depressing and almost hopeful.

Murasaki holds space for conflicting emotions. Some comics deal with Chiharu coming to terms with her children growing older. She’s saddened by the realization that they are separate beings from her, but also bewildered; at one point, her internal monologue reads: “Sometimes, I find myself looking at my children and thinking . . . Who the hell are these kids and where the hell did they come from?!” When Chiharu talks to her husband about their kids leaving the nest, he expects her to be sad, but she notes that their daughters are growing up brave and strong—what’s sad about that? And yet, as readers, we’ve seen her anguish on exactly this topic in earlier pages, so we know she’s both sorrowful and proud. Showing only one of the emotions would come across as sentimental, even trite, but instead we see the depth and range of the complexity of parenting.

Later in the book, Chiharu gets a part-time job—a move that doesn’t shift her responsibilities within the home. Now, she works even more, but her work outside the home is remunerated. In many ways, her part-time job doesn’t dramatically alter her life; and yet, it does signal an internal change—she has something that’s hers alone. While panels continue to show her without all her facial features, the phenomenon lessens. She gets a haircut. She makes dolls and, after losing her part-time job, takes her saved earnings and rents space inside a boutique to sell the dolls. While Talk to My Back doesn’t confront the mindset that artistic endeavors don’t have value unless they generate income, it’s nice to see Chiharu get paid for her creative work, given that she’s not compensated for the other work she does.

Chiharu’s burgeoning financial independence through her creative endeavors echoes Murasaki’s own life. Murasaki stopped drawing comics after getting married, but eventually began creating them again in secret. She feared her husband would kill her and knew she couldn’t raise her children with him, but in order to leave, she needed money, which she knew comics could provide. She’d call editors from public phones, “smuggle” her artwork out of the home, and meet with editors in cafés. In 1981, she was finally able to separate from her husband. She stated in an interview, “Had my marriage gone well, I probably wouldn’t be drawing manga now, so I guess I have my husband to thank for that. Thanks for putting me through hell!”

One might expect Murasaki to have infused her work with bitterness, considering her history with her husband, but Talk to My Back doesn’t read that way. While it wrestles with the isolation of marriage and motherhood, Chiharu’s husband is arguably portrayed with complexity. He’s clueless and flawed, expecting Chiharu to make his coffee, even when she’s ill, but he also tries to surprise her for their anniversary (never mind that he messes up the date) and he cancels a “business trip” when he sees Chiharu is hurt. The work’s refusal to take a binary approach is one of its greatest strengths—one that nonetheless leaves room for criticism of the institution of marriage and the way it’s touted as a gateway to emotional satisfaction. All hail the nuclear family! Only the wife will be expected to stay monogamous, and she’ll iron her husband’s clothes and cook his meals! No gratitude required! No thank you, these pages retort. Damn the patriarchy.

The work’s refusal to take a binary approach is one of its greatest strengths.

Reading Murasaki stirred up old feelings I’d forgotten—how confining my life had been, how I’d resented and envied my spouse’s freedom, how achingly lonely I’d felt. But, thanks to Holmberg’s essay exploring Murasaki’s life and the historical relevance of Talk to My Back, I found healing in the centering of Chiharu’s quest to assert her own self-worth.

When I returned to the workforce, my resume was flagging. Degrees in English and education, but my only professional work experience was a year in foster care, followed by a few months as a school counselor, and then a big five-year employment gap. Oh, how I kicked myself for my hotheaded decision to quit, replaying my old coworker’s warning that I’d never find another job like this again. Not with my background.

She was, of course, right. Luckily, I no longer considered being a school counselor my dream job. Dreams change. We grow, sometimes outgrowing relationships. Reading Talk to My Back helped me move past my ill-considered choice to quit. Yes, I could’ve—should’ve—handled it differently, but I don’t regret standing up for myself. Yamada Murasaki’s life and work is unapologetic in its declaration of the importance of championing our worth, whether we do that by leaving a confining relationship, or quitting a dehumanizing job. Not all contemporary American readers will relate to Talk to My Back’s portrayal of the frustrations of domestic life, but probably most will recognize the inherent loneliness of not truly being seen. Perhaps the book will inspire some readers to finally draw the line and walk toward personal fulfillment. From what I’ve read about Murasaki, I imagine she’d like that.