As a shy junior high student, I had a love-hate relationship with my art teacher, Mr. Krezanosky. Love, because he paid attention to me. Hate, for the same reason.

“That drawing would be half good if we could actually see it,” he’d say. “Make it darker.”

I tried, but my version of dark was featherlight. Exasperated, he gave me a Sharpie.

“You’re only allowed to draw with this,” he said. “Use some force. Tentativeness kills talent.”

I was horrified. I didn’t know how to draw with something so blunt and bold. Somehow, I managed to be just as timid with the marker as I’d been with the pencil. Mr. Krezanosky sighed. “You’ll get there someday, kiddo.”

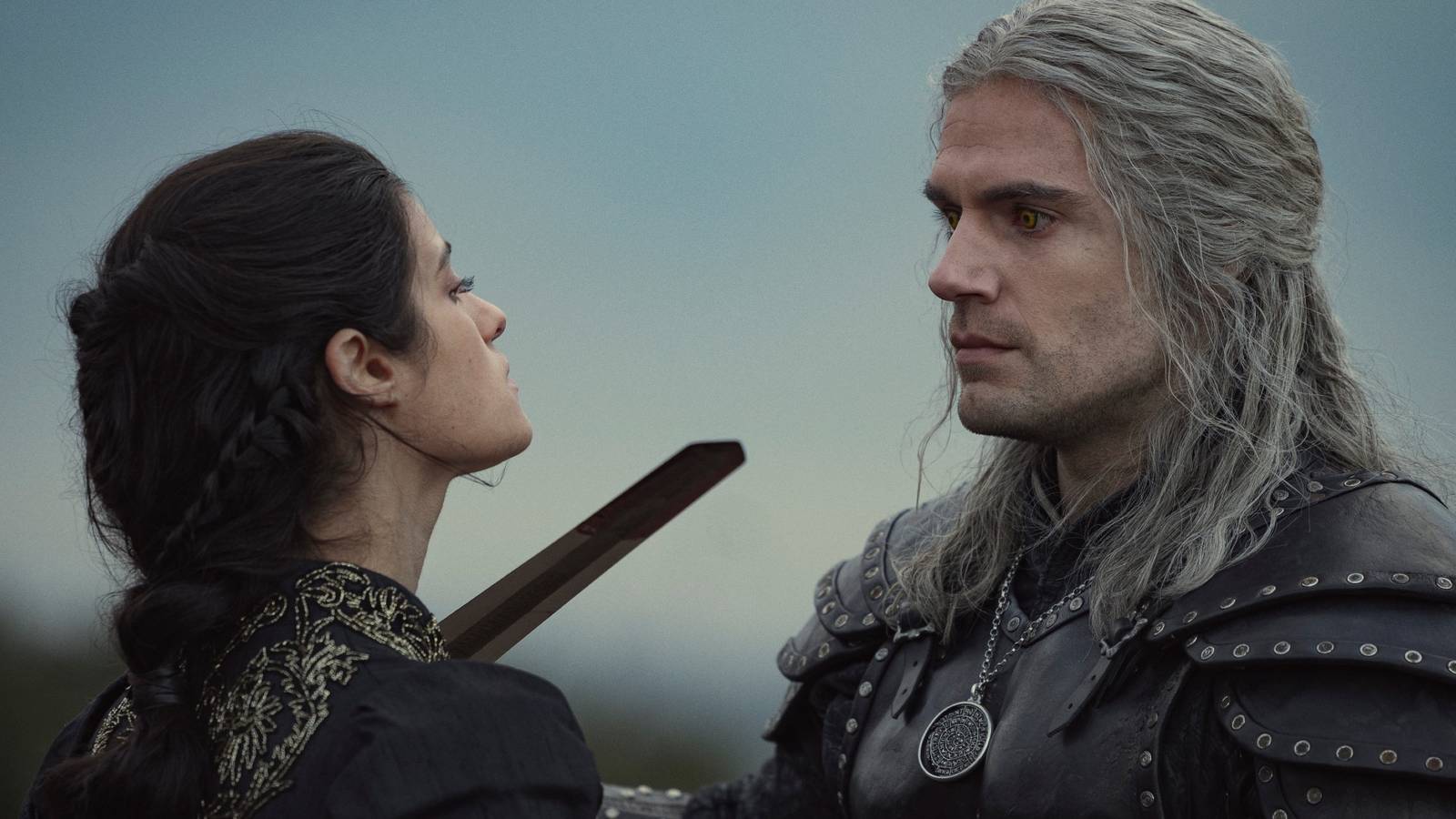

But have I? George Saunders’s new novel, Vigil, made me question how far I’ve come. Saunders’s protagonist, Jill Blaine, is a distinctly unforceful person intent on rankling no one. In other words, she’s me. A people-pleasing, Buddhist-leaning, born-and-bred conflict-avoider, I immediately recognized myself in Jill’s delicate approach. If she’s got a writing instrument in her little tan purse, I’d wager it’s a Number 2 pencil.

When I interviewed Saunders for my podcast, he confessed that he likewise relates to Jill’s kindly outlook on the world, experiencing a “generalized fondness” for strangers that makes it hard to fathom our transgressions as a species. Yet in Saunders’s case, a soft heart does not translate to a light line. Tentative he is not.

Jill is a ghost—literally. Her mission in the afterlife is to comfort the dying, a job at which she is highly successful until she meets oil company CEO K.J. Boone, a man who spurns solace. He has spent his life funding and spreading false narratives to discredit scientific findings on climate change. The book takes place at his deathbed during his final moments. Unrepentant, he believes he has contributed to human progress and is leaving the world a safer, more efficient place. He has lived a big, bold life free of pesky reflection. Force is the blood in his veins.

Jill uses her secret weapon—gentleness—to try to penetrate Boone’s haughty veneer to reach the lost little boy within, a kid teased for his shortness and backwater origins. Her outlook on the human condition is reflected in this passage about Bowman, a character from her past:

“He had left his mother’s womb with a particular predisposed mind and started living, and immediately that predisposed mind had run up against various events, and had been altered in exactly the way such a mind, buffeted by those exact events, would be altered, and all the while he, Bowman, trapped inside Bowman, had believed he was making choices, but what looked to him like choices had been so severely delimited in advance by the mind, body, and disposition thrust upon him that the whole game amounted to a sort of lavish jailing.”

I nearly tore the page underlining this passage, exhilarated to find a character who so blatantly embodied my worldview. According to neuroscientists, over 95% of our thoughts and actions stem from subconscious conditioning. We operate out of familial, cultural, and epigenetic downloads that cause us to live on autopilot. Some scientists argue that any degree of free will is an illusion. The view that this whole human game amounts to a “lavish jailing” makes room for infinite compassion, even for behavior like Boone’s, who is merely a product of his upbringing. Jill perceives that anyone born into Boone’s particular body and circumstances would have made the same choices. And so, she brings to his bedside only comfort.

I believe I generally succeed in humanizing my characters,

but do I sufficiently take them to task?

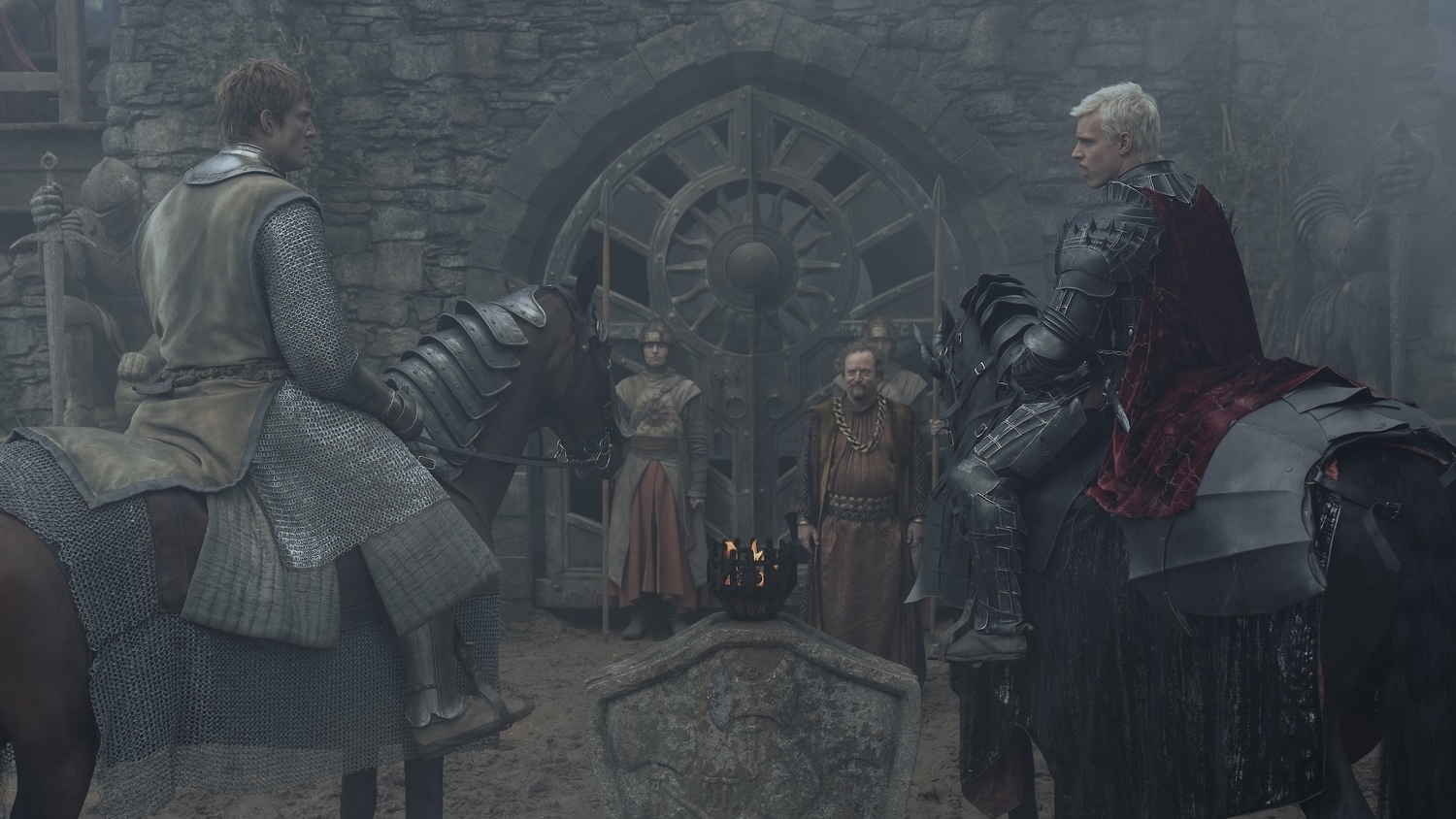

I adored her. Felt validated by her. Somehow my pale drawings of childhood felt vindicated. Yes, I thought, there’s a time and place—a deathbed, for example—when judgment must be relinquished and soft lines are called for. Yet, as in so much of Saunders’s work, as soon as my mind fixed on this conclusion, the novel stealthily toppled it over. A second psychopomp pops into the story, a furious Frenchman with a loaded backstory who comes to confront Boone with a mile-high list of his crimes against humanity and the planet. The Frenchman rebukes Jill’s soft approach, equating her sympathy to complicity. If she’s a Number 2 pencil, Frenchie is black spray paint. The two death doulas square off for Boone’s last breath, and the novel is off to the races.

The initial comfort I felt in my alliance with Jill turned to creeping unease—the kind of holy cognitive dissonance that lets me know I’m in the deep waters of living, breathing art. As a meditation teacher, I, like Jill, have come to see everyone as an “inevitable occurrence” shaped by forces beyond our control. Participating in Saunders’s Substack, “Story Club,” and reading his book on craft, A Swim in a Pond in the Rain, have bolstered my inclination to “revise toward kindness,” to ask, “who in this scene needs more love?” His novel Lincoln in the Bardo lends compassion to victims and perpetrators, each tangled in an unbidden destiny. Saunders is a Buddhist; dependent origination is a fundamental Buddhist belief that phenomena arise in dependence upon other phenomena, leaving us all interconnected.

In my own novels, I’ve savored writing unsavory characters—an abusive boyfriend in April and Oliver and a hard drinking philanderer in Dawnland. I worked to understand the roots of their particular “jailings”—not to satisfy some Buddhist precept, but because the substrate layers are what make a villain, or any character for that matter, compelling. When a narrative signals from the get-go who I’m supposed to love or hate, my engagement tanks and the fun stops. A villain who maps too closely onto a stereotype does nothing to expand the consciousness of the reader or the writer. I believe I generally succeed in humanizing my characters, but do I sufficiently take them to task? Are the two mutually exclusive?

Jill and the Frenchman remind me of benevolent and wrathful Buddhist deities. As Jill tries to console Boone, the Frenchman reads from his towering stack of accusations: “The cardinal, he shouted, feeds on bits of plastic piping. In a ballroom filling with mud, chairs squeak in objection. A groggy hippo (What hippo, I wondered, why speak of hippos in this fearful place, this somber moment?) rolls yellow eyes up at a hunter seeking its ivory canines. A juvenile jaguar creeps forward, dismembers a poodle in a bright pink jacket.”

Jill concludes the Frenchman is unhinged, yet I hear sanity in his madness. He asserts that Boone had power, knowledge, and choice. He was not a victim of conditioning, but an architect of climate catastrophe.

The Frenchman has his facts straight. In the 1970s, ExxonMobil executives had access to detailed climate data proving that burning fossil fuels would lead to global warming, yet the company publicly denied the link for decades. Just as tobacco companies refuted the health risks of smoking, oil companies deliberately sowed doubts about climate science to boost their bottom lines. Billionaires such as the Koch brothers and Robert Mercer heavily funded climate change denial. The misinformation they promoted impacted governmental policy decisions around the globe, and a disaster that could have been averted was instead accelerated. Like Boone, many of these men and women knew the truth. For the Frenchman, these decisions were not “inevitable occurrences,” but greed-driven choices made by people with extraordinary power.

“Rather than comforting him,” the Frenchman tells Jill, “I advise you to lead him as quickly as possible to contrition, shame, and self-loathing.”

Jill doesn’t buy it. But if what Boone needs most is redemption before death, isn’t leading him to contrition as forcefully as possible the most compassionate response? After all, in Dickens’s A Christmas Carol—a text which Vigil is deeply in conversation with—Marley doesn’t pat Scrooge’s hand.

In his Substack, Saunders often quotes Chekhov: “A work of art doesn’t have to solve a problem; it just has to formulate it correctly.” In Vigil, he sharpens his long held personal inquiries into free will, identity, and corporate greed, and as always, trusts us to draw our own conclusions. Tragicomic and morally lucid, the book is at once signature Saunders—you can pluck out any paragraph and know that it’s his—and wholly groundbreaking. On the Richter scale, he’s made an exponential leap.

Much of this ferocity comes from Boone himself. No sooner do I begin shifting my allegiance from Jill to the Frenchman than the story presents a third argument—classic Saunders—through Boone, who responds to the Frenchman with a scorching counter:

“You know one thing you rarely heard about in the good old U.S.A. anymore? Monsieur Frog? A young fellow dying of appendicitis. At twenty-eight. Like Grandpa’s brother had. Because a road got washed out. And the horse-drawn cart couldn’t make it through. Imagine you go back in time and drop that young guy into the backseat of a big old SUV, fly him over a perfect four-lane to some gleaming modern hospital, save his life.”

Boone asks if the Frenchman would prefer to die in the horse cart or go “zinging toward help, air-con blasting? / Anyone with a lick of sense would choose the latter. / We had. / The world had.”

Boone isn’t wrong about the benefits of modern technology. But he’s also not addressing the Frenchman’s accusation: that he knew the cost and chose profit anyway. Novels about our current Dark Age that don’t challenge or deepen our understanding lack punch. Vigil is a boxing match.

The act of writing (and reading) invites us to abide more closely within another’s consciousness than is possible even with our loved ones. It’s the ultimate intimacy. How then to embody a character as reviled as Boone, whose very smile is a grimace “shot through with a measure of forced goodwill”? Saunders told me that in order to render Boone fully, he had to give himself over to his perspective, feel the certitude of his convictions, and express them as passionately as Boone himself would. Yet, Saunders conceded, Boone is not a real-life oil executive but Saunders’s image of one. Did he get it right? There’s no way to know, but the effort is a noble one that lies at the heart of all fiction writing.

Novels about our current Dark Age that don’t challenge

or deepen our understanding lack punch.

As Boone’s life wanes, Jill nudges him toward a softer outlook on himself and those he harmed, trying her best to “revise” him toward kindness. In our interview, Saunders confessed to getting impatient with her in his early drafts. Her comforting style, successful with her previous charges, had no effect on this man. And so, it seems to me, Saunders revised not toward kindness, but fierceness—that is, fierce attention to what the story was telling him. Jill’s old bag of tricks didn’t cut it anymore. She had to come up with a bolder approach. In doing so, she becomes less wispy and tentative, more distinctly herself.

As we spoke, I felt my case for my Number 2 pencil—in writing, in life—further eroding. Yet, would I rather be Boone, a man who drilled bold lines in the world and left wreckage in his wake, or Jill, who lived and died without leaving a trace? A pencil, after all, is low impact and erasable. In writing and in living, I’ve chosen—or inherited—the softer tool. I may not have managed to draw with a Sharpie, but at least I didn’t clearcut a rain forest.

“Oh no?” asks the Boone in my head. “What about all the times you’ve driven your SUV—hybrid to assuage your guilt—while sipping from a throwaway coffee cup? How many goddam trees did that cost?”

“Fine,” I say, “but passive participation is not the same as deliberate orchestration.”

“Passive?” he says. “Does the car pump its own fricking gas? Is your air travel an inevitable occurrence?”

Oof. Nailed.

Boone points out that big actors rely on small actors. If I believe I had no part in “the world” deciding on progress, I’m a fool. Not leaving a bold mark doesn’t mean I’m innocent; it means I’m afraid of owning my power—and I have been for a long time. But I can’t hide behind pencil lines anymore. There’s no such thing as a passive participant when the house is burning down. I’ve walled myself off, but smoke is seeping through the doorjamb. Faced with the Frenchman’s accusations, Boone becomes aware of “the wall that must be continually maintained between himself and certain complicating admissions.” You and me both, Boonie.

Not leaving a bold mark doesn’t mean I’m innocent;

it means I’m afraid of owning my power.

One night while writing this, I dreamed of smoldering drones attacking protesters on a college campus. Caught in the chaos, there was no way for me to fight back. I did what seemed the most radical choice available. I sat on the pavement and meditated. Not to “pray away” the evil, but to invoke a fiery sword of inquiry: What walls have I built between myself and certain inconvenient admissions? What delusions do I maintain to fuel my personal bubble? If dependent origination is as true as modern science suggests and we are all intimately connected, the best thing I can do to abate our collective unconsciousness is to nudge my percentage of autopilot down a point or two, become slightly more intentional than inevitable.

Not so easy, it turns out—for me or for Jill.

Like Boone, Jill maintains a wall between herself and particular memories that, if allowed to surface, would complicate her work. She and Boone each practice their own form of denial, neither able to “expunge some clinging last bit” of themselves because that “bit” has never been brought into the light of awareness. Nevertheless, fragments surface that our dear girl would rather not acknowledge, stirring a wrath she didn’t know she could muster. In Buddhism, wrathful deities use their swords to cut through delusion as a means of fierce compassion. When free of self-interest and guided by wisdom, rage can be a powerful tool for liberation. The Frenchman’s fury isn’t cruelty. It’s clarity.

In Vigil, the picture of compassion drawn in the opening pages transmutes into a truer version of itself. Such metamorphosis becomes possible when we abandon our preconception of our work in order to ruthlessly listen to it. Saunders calls writing “a species of meditation,” and when he quiets his mind, in walks hilarity. Boone is visited by a host of people and birds, living and spectral. We can almost feel Saunders’s surprise as each new arrival materializes. He’s a kid in a sandbox, shutting out any “shoulds” convention might impose on him. His wild imagination springs from playful curiosity. Vigil is as funny as it is dark.

I’ve come a long way since Mr. Krezanosky’s class. I’ve learned that conflicts don’t get resolved by hiding under the bed. I still don’t like arguments, yet when they happen, I’m more able to stand in the fire with calm curiosity. But how about my writing? Have I outgrown my Number 2 pencil and learned to commit to a line? I’m working on a novel set in China, where I lived for several years before and after the Tiananmen massacre. I strive to understand my characters’ lavish jailing, to humanize without exonerating, to hold the paradox of conditioning and accountability. In Buddhist iconography, the blade is two-sided for a reason. One edge severs inner delusion, the other, outer. Are both edges of my sword equally sharp? Let’s just say after readingVigil, I’m investing in a whetstone.

Good stories, like suspension bridges, are held together by the tension of opposites. I’m learning slowly, tentatively (old habit), that this is true in life too. We need empathy as well as judgment. Understanding as well as rage. Literature in the age of the Anthropocene needs writers who can do what Saunders does in Vigil: keep us on the razor’s edge of paradox without collapsing us into facile conclusions. Because sometimes rage isn’t the opposite of compassion—it’s compassion with a spine. It’s what love looks like when it isn’t afraid to draw a bold line.