How do you discuss something so intimate and uncomfortable as finding a spouse, without laughing or crying or cringing in embarrassment or fear? How do you talk about it without using the L-word? As in Luck. As in, you can plan and strategize as much as you want to, you can prepare as if you’re preparing for battle, you can organize and plan for all contingencies. There is still a certain amount of luck involved.

More on that later.

Frequently it is a different L-word. As in Laugh. It’s a laughing matter — as in when you see it on TV or the silver screen, you end up laughing at either the future groom or the bride, or perhaps both, for all of the misunderstandings and all of the foibles. Sometimes you’re laughing out of relief: As in “Thank god that isn’t happening to me.” Sometimes you’re laughing in recognition: “Been there, done that!”

Perhaps it’s not just two people getting married but two families and two communities coming together.

There is a romantic presumption of happily ever after, of marital bliss. There are the underlying assumptions that maybe your family does know what’s best for you, that perhaps it’s not just two people getting married but two families and two communities coming together. Perhaps it shouldn’t be left to the young and inexperienced to figure out for themselves. Think We Are Lady Parts. Think Indian Matchmaking.

Then there’s the comedy of errors when the groom or bride deviates from the chosen path that is meant to make us laugh, to ease the cringing and the uncomfortable moments. Think of Kumail Nanjiani in The Big Sick or Nia Vardalos in My Big Fat Greek Wedding.

But in real life, arranged marriage is no joke.

(I will not directly discuss child marriage because this essay is supposed to be funny and there is nothing funny about the practice that in 2022 is alive and well in 44 states in the U.S. and all around the world regardless of border or boundary.)

(Because patriarchy.)

(Because misogyny.)

It is an accepted practice around the world. Most of the time, in my experience with my family and friends and acquaintances, marriages are arranged with good intentions.

Still, India and the subcontinent remain in the news — so much violence and oppression against women.

In India, where my ancestral family originates, it is complicated. Here is a nation famous for worshiping female deities such as Durga and Kali, tongues out, weapons in hand. And India had its first female prime minister, Indira Gandhi, decades before the purported democratic ideal, The United States, fielded Kamala D. Harris to the nation’s second highest position. Still, India and the subcontinent remain in the news — so much violence and oppression against women. Child marriage, yes, but also dowry deaths and female infanticide and sexual assault.

But I digress, again.

Arranged marriage ultimately becomes something borne out of a visual medium: think picture brides. Someone posing, unsmiling, that is supposed to symbolize a potential bride or groom’s merits and seriousness. There are many stories and books about that concept — famously, Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni’s short story collection, Arranged Marriage, and The Buddha In The Attic by Julie Otsuka which vividly depicts the lives of Japanese picture brides emigrating to the United States and making their way in the years before World War II. Kiran Desai’s debut novel, Hullabaloo In The Guava Orchard, has one of the best descriptions of the expectations of and for a daughter-in-law that I’ve ever read, and I chuckle every time I have a moment to revisit it.

For as long as I can remember the dominant American culture has looked upon arranged marriage in eastern cultures or non-English speaking parts of the world as something backward or something that was to be treated as abusive or suspicious. Of course everything in the world is a circle/cycle and there are now healthy numbers of Americans on eHarmony or Matchdotcom or something similar trying out a more modern version of arrangement and the institution of marriage.

My family and my husband’s family hail from similar backgrounds. We are both academic brats, children of college professors. In fact we were both raised in the U.S., Bengali in origin — and our parents are friends. Yes, we were introduced but as we are fond of saying, “We got married despite our parents and not because of them.”

You can’t look to the future unless you know where you come from.

That was the nutshell of our arranged marriage story, our “sommondo” from thirty-plus years ago — More later.

Now, I offer origin stories. You can’t look to the future unless you know where you come from —

On my Baba’s side, there are three important moments:

- My dad’s paternal aunt was the first female police inspector in Kolkata, and she chose not to marry (how I longed to be a fly on that wall and learn how that came about).

- My dad’s maternal aunt Khuku Roychowdhury, died following a violent dispute at the hands of her mother-in-law, as depicted in my recently published novel, Circa.

- And my paternal grandmother, Kalyani (whom we lovingly called Rani-Ma), was married at 13, and had her first baby at 15. When my grandfather died at age 42 of leukemia, my Rani-Ma was a widow at the age of 31 with seven kids to feed.

On my Ma’s side, I have the visual aids to accompany these stories:

- My great grandmother was married off at 9, in India, and went to live with her in-laws a couple of years later. Her husband was a widower at 22 with a toddler. My great-grandmother had my grandmother at 12. I have my grandmother’s, my didima’s, summondo photo. She is 13, thin in her sari and embroidered blouse, somber.

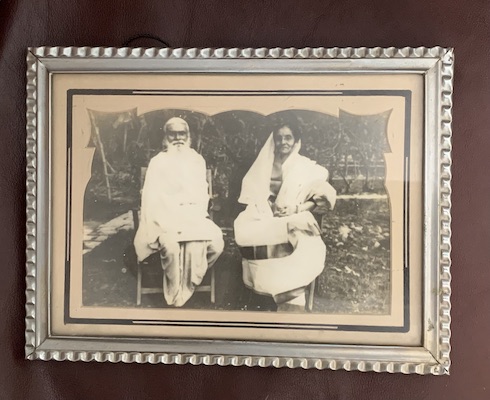

- I have a photo of my mom’s grandparents from 1970 when I was four years old — my great grandfather is a very old man with a white beard and my great grandmother is still young, her hair a long rope of jet black. By the time this photo is taken my mother is around 30 and has been married for seven years — and has little ‘ole me in tow.

- I also have a photo of my grandmother and her mother standing side by side when my grandmother is a new bride at 14 and her mother is a grand old mother-in-law at 27. They could be sisters (not pictured).

I know I’m lucky I have these photographs – not everyone does.

Like one set of parents in Circa, my mom’s dad and my dad’s mom grew up in the same village.

My parents and my in-laws were born and brought up in India. Just like one set of parents in Circa, my mom’s dad and my dad’s mom grew up in the same village and each family moved away. After a prolonged absence, they ran into each other in Kolkata on a Monday in August 1963 and by that Friday, my future mother and father met each other as they married. (My mom likes to recount how much she threw up from the moment she was told she was marrying, on Tuesday, until she actually got married on Friday).

I have a photo of my parents shortly after they married. My future dad looks affable. My future mom looks like she’s about to shoot lava out of her eyes ☺. (Next year, they will celebrate 60 years of marriage, so I guess their parents chose….wisely.)

My mom became part of my dad’s family, in a joint family living situation for the first year ( i.e. she moved into a house that accommodated mom, sisters and brothers, uncles and aunts, cousins – all under one roof). My parents left for the United States in 1964, ostensibly so my dad could work as a visiting professor, first at UC Berkeley and the UNC, and then go home. But then the economic opportunities and the children came along. They remained, became American citizens.

Meanwhile, my in-laws cheated a little in the arranged marriage department: They each happened to be graduate students at the University of Illinois where they met during a social function. 1958. My late father-in-law earned his PhD in physics before my mother-in-law finished her PhD in mathematics (one of the first Indian women to earn a PhD in the U.S.) and went back to India. He played coy for two years, rejecting many a summondo, until my husband’s mother returned home with PhD in hand, and then both families were told that they had met and wished to marry.

They married in 1962, my future husband was born a year later and then they returned to the United States permanently in late 1964 or early 1965. They were both at UNC for a short time before taking permanent faculty positions at Clemson University. But no one on this side of the Indian Ocean really knew their marriage story until recently (thirty years after we lost my father-in-law to lung cancer). From the outside it was a huge coincidence that they both earned graduate degrees and happened to have an arranged marriage.

What I really want to impart is the frozen nature of time.

Nudge nudge. Wink wink.

What I really want to impart is the frozen nature of time. As in, the minute our parents left India, India froze in time for them. India and its cultural norms and its expectations remained firmly stagnant. 1960s. Of course, they heard stories of, (shock, horror) infidelity, separation and divorce. But they were few and practically non-existent next to the stories that our families watched weekdays on “As The World Turns” and “Guiding Light.” And that soap opera loving culture has permeated into the group consciousness of immigrants, especially in my extended family. Things that were deemed “American” were deemed worthy of suspicion, that Americans allowed another L-word to guide them: Love.

But I digress.

I suppose everyone’s stories are similar in a way but also vastly different. Arranged marriage is similar for everyone in the hopes that you don’t end up with someone truly awful, and that you end up building a life together based on trust and affection. But all paths are vastly different because of the intersections of different life experiences. Still I must say at least the children of the 60s that I grew up with truly did try to buy into their parents expectations and keep the peace and keep the cultural continuity going. We may have tweaked a bit here and there but genuinely we tried to balance our family’s hopes with our own. Most of my peers had some modified form of arrangement, most of them had negotiated hard for the ability to say no. I don’t know what it’s like nowadays, and I don’t have any interest in finding out. I have children but I wouldn’t be caught dead trying to arrange so much as a coffee date much less a spouse ☺.

There is a gender gap here. Women still have it much worse than men. Ultimately we still live in the patriarchy no matter what. So if a man doesn’t like the proposed arrangement for whatever reason, his ability to say no has a higher success rate than a woman’s ability to decline. I had horror stories in my summondo experience — one of them is in Circa, fictionalized version to be certain but its origins are in real life. I remember fighting back and pointing out obvious flaws in the potential grooms. I remember negotiating with my parents, and garnering veto power. My husband’s stories are very funny and I think encapsulates all of the hopes, expectations, regrets and misunderstandings that come with this seemingly interminable process (after all, when you’re in your 20s, everything seems interminable).

I remember negotiating with my parents, and garnering veto power.

In this way my husband and I are truly lucky. We had parents who cared deeply, and we both had some sort of veto power and when we finally were introduced (well re-introduced, apparently we played together as kids the same way my mom’s dad and my dad’s mom were friends long ago), we were veterans of the summondo process.

My summondo story has a postscript. A few years after we were married I was in graduate school and I had to write a short story on short notice. Flummoxed by the deadline I called my husband. It was in the pre-cell-phone, pre-internet days and I held the receiver between my shoulder and ear and typed his answers as I recalled some of the details of some of the stories he told me. I typed and asked questions, prompted details about some of the moments where the introduction went south (there was the time he and his father fell asleep on the couch after a big lunch and his father was caught snoring…there was the time the potential bride wouldn’t speak to him except to say she thought Sylvester Stallone and Rambo were the best…).

My teacher loved the story.

It, well, made him laugh.

![[Spoiler] Evicted, Final 4 of Season 25 Revealed – TVLine [Spoiler] Evicted, Final 4 of Season 25 Revealed – TVLine](https://washingtonweeklytimes.com/wp-content/themes/jnews/assets/img/jeg-empty.png)