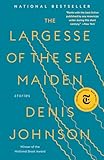

Denis Johnson familiarized himself, early and often, with life’s bleakness. Between his roving childhood in Tokyo and Manila, a heroin addiction that ended in the mid ‘70s, and fabled drinking binges with his teacher Raymond Carver, the author’s confessed depravity—“I’m not right in the head,” he said in 2002—forms the moral axis on which his stories operate.

Like moths to a flame, or more appropriately, barflies to a long countertop, Johnson’s characters can’t resist self-sabotage for more than a few pages at a time. They’re both a reflection of the author’s hard living and a conduit for his seemingly endless supply of dark humor.

“Dear Satan,” broods a detoxing narrator in Johnson’s 2018 collection The Largess of the Sea Maiden, “I did not enjoy it at your Jamboree last night.”

“This kind of shit just keeps happening until you’re dead,” says Bill Houston, ex-con at the heart of 1983’s Angels, after a lighter explodes in his hand.

“This kind of shit just keeps happening until you’re dead,” says Bill Houston, ex-con at the heart of 1983’s Angels, after a lighter explodes in his hand.

“I will not go to Jesus!” says a Death Row inmate later in the same novel. “I am an alien from another planet. I was not meant to be saved.” (To which his captive listener responds, “I admire your spunk.”)

You don’t read these books looking for heroes—you read them to inhabit, if just for a moment, the mindset of delinquents and outcasts. This is the Johnson experience: part cautionary tale, part curio, executed always with breathtaking beauty.

Johnson, who died in 2017, was a National Book Award winner, two-time Pulitzer finalist, and the recipient of the Library of Congress Prize for American Fiction. George Saunders called him “Our most poetic American short-story writer since Hemingway.” It’s therefore curious that, despite wide recognition within the world of letters, Johnson’s renown hasn’t crossed into household lexicon in the manner of some recent greats (Egan, Whitehead, Franzen).

Perhaps this has to do with Johnson’s conventional surname, or the onerous length of his 2007 award-winner Tree of Smoke. More likely it relates to subject matter.

Perhaps this has to do with Johnson’s conventional surname, or the onerous length of his 2007 award-winner Tree of Smoke. More likely it relates to subject matter.

For readers looking to familiarize themselves with Johnson’s work, I recommend starting at the end and working backward. The Largesse of the Sea Maiden, published a few months after Johnson’s death, represents a solid jumping-off for its varied backdrops and relative buoyancy. By this point in his career—long sober and much lauded—Johnson came as close as he would to a depiction of “mainstream” characters, for example an advertising whiz and an Elvis Presley afficionado. Distanced from the ruckus of his youth, the author painted these protagonists in comparatively mellow tones, even keeping some of them out of jail.

Rewinding half a decade in his career and a century on the page, Johnson’s novella Train Dreams, originally published long-form in The Paris Review, is a must-read saga of the Wild West railroading boom, a contemplation on loss, loneliness, and ambition set in bucolic Idaho and Washington. Digestible in a single sitting, the meditative work split 2012’s Pulitzer vote with David Foster Wallace and Karen Russell—not bad company.

Rewinding half a decade in his career and a century on the page, Johnson’s novella Train Dreams, originally published long-form in The Paris Review, is a must-read saga of the Wild West railroading boom, a contemplation on loss, loneliness, and ambition set in bucolic Idaho and Washington. Digestible in a single sitting, the meditative work split 2012’s Pulitzer vote with David Foster Wallace and Karen Russell—not bad company.

“The book that meant the most to me this year was Train Dreams by Denis Johnson,” wrote Zadie Smith that December. “I don’t have anything intelligent to say about it. I just thought it was very beautiful.”

For the stronger of heart, or those looking for total immersion, Johnson’s 2007 epic Tree of Smoke— praised in the New York Times as “something like a masterpiece”—finds him at his most ambitious. The mammoth work follows CIA operative Skip Sands from the Philippines into 1960s Vietnam, where his uncle “The Colonel” has been spinning webs of subterfuge and nihilism:

You’re sad about the kids, sad about the animals, you don’t do the women, you don’t kill the animals, but after that you realize this is a war zone and everybody here lives in it. You don’t care whether these people live or die tomorrow, you don’t care whether you yourself live or die tomorrow, you kick the children aside, you do the women, you shoot the animals.

Meandering, philosophical, and decidedly uneven, Tree of Smoke sparked controversy in the way of any great thought experiment. “Excessive and messy,” said The Guardian. “Astonishingly bad,” wrote one critic in The Atlantic, citing the novel’s “jumble of language levels.” After it won the National Book Award, fans and detractors doubled down. If my personal surveys are any indication, legions of readers saw the ochre hardback waste away on their nightstand, where it will eternally be known as “that one with the monkey.”

Fifteen years before Tree of Smoke, Johnson broke into the cultural imagination with his 1992 short story collection Jesus’s Son, in which a narrator referred to as “Fuckhead” recounts a whirlwind of drug-addled misadventures. When Jesus’s Son was adapted for a 1999 feature starring Billy Crudup, Jack Black, and Michael Shannon—a “scruffy, likeable new film” said 34-year-old A.O. Scott—it seemed that Johnson had officially “made it.” For better or worse, his outlook on the page remained dire.

Fifteen years before Tree of Smoke, Johnson broke into the cultural imagination with his 1992 short story collection Jesus’s Son, in which a narrator referred to as “Fuckhead” recounts a whirlwind of drug-addled misadventures. When Jesus’s Son was adapted for a 1999 feature starring Billy Crudup, Jack Black, and Michael Shannon—a “scruffy, likeable new film” said 34-year-old A.O. Scott—it seemed that Johnson had officially “made it.” For better or worse, his outlook on the page remained dire.

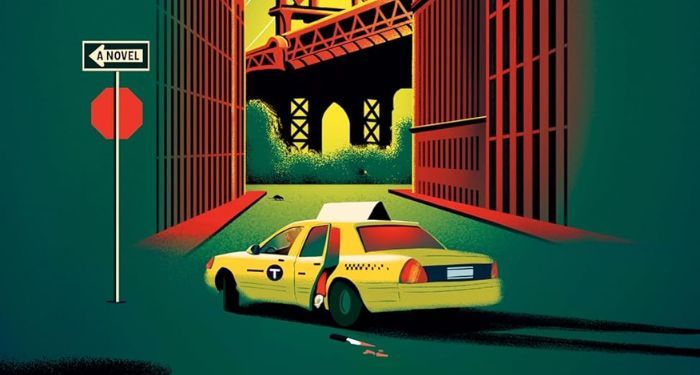

Here, a belated admission: I originally meant to write a standalone critique of Johnson’s first novel, Angels, which hit the shelves back in 1983. But reviewing Angels in a vacuum, I reasoned, would disservice all that came after it. Especially when so many are unfamiliar with Johnson’s catalog.

When I noticed a reissued Angels spine poking from the bargain section in Denver’s Tattered Cover Book Store, I wondered if Johnson’s career might have begun on a similar note where it wound up. The answer? Of course it did.

In Johnson’s full-length debut, a 200-page humdinger as peculiar as it is ambitious, we find housewife Jamie Mays fleeing her abusive marriage with two young daughters in tow. Despite, or maybe because of her guardianship, Jamie befriends a man a few seats back on the Greyhound, a Navy vet by the name of Bill. At this point, everything more or less goes to hell.

A pleasure-seeking narcissist who also stars in Tree of Smoke, Bill Houston isn’t the type of person Jamie should be following around. Unfortunately, when she loses track of him in Chicago, things get worse. Much worse. Ushered by Bill from rock bottom to something a few steps away, Jamie meets the other Houston siblings, who decide for no particular reason—gin, probably—to rob a bank.

“The smoke of gunfire lay in sheets along the air around his head, where light played off the fountain’s pond and gave it brilliance. In the center of his heart, the tension of a lifetime dissolved into honey. He heard nothing above the ringing in his ears.”

For that of a 30-year-old newcomer, Johnson’s prose was already a rare beast, veering here toward Hemingway’s pep, there toward McCarthy’s panorama. One presumes his teacher Raymond Carver had a hand in this. A simpler explanation would be a lifetime of reading, much of it spent at society’s margins.

By the sordid finale of Angels, cameras pan to “the deep emptiness of the pre-dawn heavens, the imperious stupor of the Arizona State Prison Complex,” where Bill has been sentenced to Death Row for his role in the robbery. “And over all of the dawn of execution day, the desert night’s dry foreboding, the negligent powerful breath of the day’s coming heat, the heat that burns away each shadow and incinerates every last particle of shit inside the heart.”

“Mr. Houston?” ventures a guard. “Let’s take you for a ride up that pipe.”

Some readers would have known even then, in the early ’80s, that Angels was the start of something. Like the chest-full of lead Bill Houston poured into that luckless security guard, Johnson’s oeuvre feels like something we didn’t deserve but got anyway.