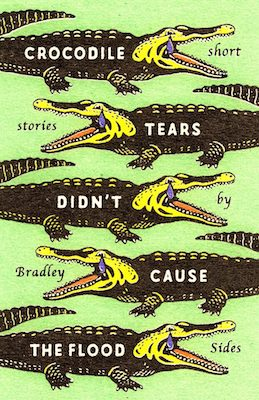

In his 1917 essay “Art as Device,” Russian formalist Viktor Shklovsky coined the term “defamiliarization” as a goal of the artist. To “defamiliarize,” simply stated, means to make the familiar appear strange or new. In other words, art should help us “re-see” our ordinary, mundane surroundings in a different way. In Bradley Sides’ new story collection, Crocodile Tears Didn’t Cause the Flood, the weaving of fabulist and fantastical elements into an ordinary modern world is seamless and persistent, leaving readers to believe that monsters and magic are indeed all around us.

The collection is populated with Pteradons and vampires, shark-children and dragons, people transformed into moths—and yet the primary takeaway for the reader is not escapism, nor magic, nor fantasy, but instead the opposite: these stories usher us into universal emotional states of grief, loss, and desire. The world we recognize is defamiliarized, made strange and new, which works to bring to the surface those conflicts and questions that are part of every human’s experience.

Another way Sides defamiliarizes the world is through the use of forms—recognizable forms like letters, police interview transcripts, instructions, exams, and others that set up the reader’s expectations and then subvert these expectations. The result is an array of storytelling modes and experiences that feels both fresh and original and yet comfortingly familiar.

Sides’ collection, with its playfulness and range, is hard to categorize and a joy to read. Is it realism? Is it fantasy? Is it magical realism? Comedy? Drama? Yes, all of this and more.

Darrin Doyle: I picked up a definite fable vibe in many of these stories. Some feel like allegories, while others employ fairy tale tropes like humans transforming into animals. Were you influenced by myths and fables in writing this collection?

Bradley Sides: Absolutely, but not in a traditional sense. I really love contemporary work, so I find a lot of inspiration in today’s writers. Daniel Wallace, for example, is a huge influence. His novel Big Fish, which has mythic and fable-like elements, was the first time I saw literary magic in the South. I’ve probably read that book fifty times, and I’m serious, too. I’m also influenced by the stories of our best magical realists like Karen Russell, Kelly Link, and Alexander Weinstein. There’s so much good work out there that’s engaging with the elements you mention.

DD: Themes of grief and mortality come up often in these pieces. Do you think about allegorical potential before you begin writing, or is this something you notice only after you’re finished drafting?

BS: Grief and mortality are two of the major focuses of my writing. I might argue they are the major focuses of my work. Many of the texts I hold closest approach both of these things so closely. Just looking back at Big Fish, for instance, the novel is largely about dying and death—our lasting story or legacy, whichever you want to call it. It’s on the first page up until the end, and I think that’s true to life. When we learn what death is, it tends to haunt many of us. We think about not only our own death, but we also think about the death of all the folks we love. It’s always there—and there is no escaping it.

I tend to let my stories develop as I write them. I’m not much of a planner or an outliner. When allegorical elements might enter, they aren’t intentional. I oftentimes learn from readers what my stories are about, and that’s usually something related to grief and/or mortality. When I’m in the process of writing, my stories are, to me at least, just stories.

DD: What draws you to using the fantastic in your stories? Do you think magical realism can address real-world conflicts as effectively as standard realism, and if so, how?

BS: I probably sound ridiculous saying this, but for me, the magic is the truth. I grew up on a farm in very rural Alabama. My company was oftentimes bullfrogs, cows, nighttime’s total darkness, and occasional flickering stars. There was a lot of room to get lost in that world—to let imagination take over. And my imagination felt as real as anything else.

It still does. When I am able to travel and see a volcano, I can’t just admire the volcano. I see what it might contain and what it might be able to do. When I’m at a museum, I can’t just see a skeleton. I imagine where it was and what it did. Maybe even what it wishes it could still do.

The fantastic has power because it can’t really be contained. There’s a truth in that limitlessness that is special.

DD: I love that—the limitlessness and power of imagination. To continue the thread of grief and mortality, a number of the pieces deal with the loss of loved ones, and they show scenarios where the dead are literally brought back or visited. Not to get too philosophical, but do you think fiction is a sort of wish-fulfillment in that regard?

BS: That’s a tough one. I see fiction as being a means to explore possibilities. Maybe it is a way to give people their wishes, but maybe it is also a way to explore their fears.

There’s power in fiction, and as readers and writers, we get some of that power extended onto us.

DD: A number of these stories—“Our Patches,” “Raising Again,” “To Take, To Leave,” and “The Browne Transcript”—hint at the apocalypse through some kind of environmental disaster or other doomsday scenario. Obviously, climate change is a topic of some urgency at the moment. Can you talk about what draws you to this subject?

When we learn what death is, it tends to haunt many of us.

BS: I love this question, Darrin, and I’m just now realizing how apocalyptic this collection really is. Ha! Fear is probably the short answer. The world seems to be dying, and that’s scary. Writing about the world ending gives me a way to harness that fear and maybe try to make sense of it. Or maybe even to prevent it. Or accept it…

DD: Haha, yes. There’s that wish-fulfillment again, or maybe “coping mechanism” is a better way to put it. Your stories also present “monsters” (giant lizards, vampires, dragons, Pteradons, and more) existing in “modern, real-world” settings. You seem to raise questions about what defines a monster —and by extension, what defines a human. Can you talk about this?

BS: I am especially interested in how the two intersect. I always have been. It’s one of my major interests as a writer of weird/speculative/magical things. Humans can certainly be monstrous; they can also be good. Monsters can be humane; they can also be evil. With these stories, I want to show the various sides of humans and monsters, but I want the actual power of classification to extend a bit further to the reader—to give that person experiencing the story the agency to decide if a character is more human or more monster and for them to also create their own evaluation criteria. Maybe humans and monsters aren’t all that different? Maybe they are? As a fiction writer, I like my stories to pose questions that I don’t really answer. I’ll leave that part to the reader because that’s part of the fun.

DD: I love your use of forms throughout the collection. You have a story in instructions, a transcript of a police interview, an exam, a letter, a choose-your-own adventure, and others. What are some advantages and disadvantages to this sort of storytelling?

BS: Thank you. I appreciate you saying so. I wrote most of Crocodile Tears Didn’t Cause the Flood during the peak of COVID. I had to feel like I was having fun in order to write because those were some dark days. If I wasn’t having fun, I wasn’t writing. It’s that simple. Experimenting with form allowed me to truly be excited in what I was creating. I wrote quickly. I was laughing and failing and trying again and succeeding. It was just a really cool writing experience that will probably never be topped, and at the end of the day, the collection does and says what I want it to.

As for disadvantages, that’s tough. Some readers will probably just say, “No thanks.” Or they might shout, “Gimmick!” Haha! The experimentation might not be for them. No book is for everyone, and that’s just how it is. I’ve accepted it, and I’m cool with it.

DD: I’ve written in forms like these, and while it’s liberating and fun, the form itself sometimes dictates that you can’t use certain story elements such as setting or dialogue. For example, in “Nancy R. Melson’s State ELA Exam,” which is in the form of a test, you probably can’t include a lot of dialogue or setting. Was this ever a challenge for you?

BS: Very true. There are limits, but all stories have some brand of limit. Different worlds offer various rules that can and can’t be broken. The same with characters—or a multitude of other elements. As I was writing these stories, the form never came first; instead, the form was a way for me to tell the story I needed to tell. If I would’ve approached each story with a specific form I had in mind that I wanted to showcase, I would have been in bad trouble. I would actually probably still be on the first story. It just wouldn’t have worked.

Writing about the world ending gives me a way to harness that fear and maybe try to make sense of it.

With “Nancy R. Melson’s State ELA Exam,” the lack of usual dialogue could be limiting, but the story finds other ways for voices to come through, especially the titular character’s. The test and, as a result, the story both become extra interactive, and that’s because the form allows additional layers.

Thankfully, the many forms throughout the collection came naturally.

DD: In blurbs for your previous book (Those Fantastic Lives), you’re described as a Southern writer. Do you consider yourself a Southern writer, and if so, what does that mean to your fiction?

BS: I’m glad you asked this question. I fully embrace the label. I am a Southern writer—and a rural one at that. Like I mentioned earlier, I’m from Alabama. I’ve lived here my entire life. I’m sure I’ll die here. I talk slowly—and with a very thick drawl. I sit on my porch and tend to my little garden, all while drinking tea. For me, to be a Southern writer means to respect the place I write of and from. It means to respect the people, too. I try to capture the voices I know from down here as fully and authentically as I can. I try to treat the place with love, while being aware of the problems and flaws as well. I treat the South like it’s a character—a major one. I have to.

With Crocodile Tears Didn’t Cause the Flood, I go even further in being a Southern writer, I think. Many of the stories, including “The Guide to King George,” “Dying at Allium Farm,” and “Nancy R. Melson’s State ELA Exam,” are set explicitly in Alabama and Tennessee, and even the ones that aren’t stated as being in the South still have that Southern feeling.

DD: I did notice that there’s a focus on rural settings in the collection. Aside from this mirroring your own childhood experiences, are there other reasons you gravitate toward the rural over the urban?

BS: The honest answer is that I just don’t know that world. I’ve been fortunate to be able to travel quite a bit as an adult, so I’ve experienced it. But I don’t know it. When I’m in cities, I feel like I don’t belong. It’s like when I try to write a story that doesn’t contain magic; I feel like a phony. Focusing on rural settings that I understand is a way for me to keep a sense of truth in my worlds—and, consequently, my work. I don’t really agree with the famous advice to “write what you know,” but in this case, I stick to it.

DD: How did you decide on the title for the collection?

I see fiction as being a means to explore possibilities. Maybe it is a way to give people their wishes, but maybe it is also a way to explore their fears.

BS: Man, I’m terrible at titles. I got lucky with my first book. Those Fantastic Lives was a good one. With Crocodile Tears Didn’t Cause the Flood, I was near the end, and I was struggling with the title. Like really struggling. None of my stories worked as titles for the larger book. I didn’t want to go outside the stories because it would get bad. Death and Apocalypses isn’t very catchy. It’s probably the opposite of catchy. I was lost. Then, I began working on “Crocodile Tears Didn’t Cause the Flood.” It’s a fairy tale. It has a major flood. There’s lots of magic—and hope in the emptiness. It is a Bradley Sides story in all ways. When I finished it, I knew it had to be the closer for the collection. It feels very definite as it ends, and it just feels right in the spot.

When I stepped away and looked at the shape of my collection, the opening story is about a flood. The closing one is about a flood. There are other kinds of floods, metaphorical and literal, throughout. Crocodile tears, those big, showy, fake things, don’t cause the floods in the collection. Instead, the floods are brought on by truths—painful and beautiful truths. I knew I’d found my title, and I never questioned it.

DD: Which of the stories was the most difficult to write, and why?

BS: I have to cheat and pick two. “Claire & Hank,” which is about a guy and his dinosaur sister, and “Dying at Allium Farm,” which drops readers in on a vampire family’s organic garlic farm. These stories are actually two of my favorites in the book, so I ultimately feel good about the fight they gave me. But the struggle. The struggle…

As a person, I think I’m pretty funny, but as a writer, humor is tough for me to get right. With “Claire & Hank,” I wanted to balance humor and lightness with some real heaviness. With “Dying at Allium Farm,” I wanted the same kind of approach, except with a bit more humor. I wanted readers to laugh, but I also wanted them to feel something a bit heavier at each story’s end. I couldn’t get those endings right. “Dying at Allium Farm” went through roughly 20 edits. “Claire & Hank” didn’t take quite that many, but I kept reworking that last image.

Revision. Revision. Revision. That’s the struggle of all us writers.