The pattern first appeared to me in the school uniforms of my cousins: crisp, clean lines of navy and evergreen intersecting at perfect right angles. These uniforms, like everything else about my cousins’ lives, I envied desperately. First and foremost, I envied the fact that there were three of them and only one of me, my parents’ boring prized jewel. Furthermore, the cousins had a rotating cast of nannies that their parents—busy with a secret-clearance government job, the Army Reserve, and law school—found by posting ads at the local laundromat. The nannies never lasted long, and my three cousins once outsmarted the worst one, an old German woman named Ana, with an elaborate ruse to lock her out of their house.

Onlookers might have found it sad, but I found it fascinating: how utterly Dickensian my cousins’ childhoods were. Their lives under the reign of these strange babysitters reminded me of my favorite child protagonists, like orphan Annie or Matilda. How magnificent to be united against a terrible adult! I spent as much time at their house as my parents would allow.

When they returned home from school at 3:30 PM, they ran upstairs to their rooms. Which room belonged to whom and which siblings had to share was constantly up for debate and it seemed to fluctuate monthly. They shed their uniforms for the T-shirts and jeans they’d been aching to wear all day—regular clothes, boring clothes, clothes I could wear whenever I wanted. Their shirts and pants and jumpers lay crumpled on the floor, the patterns no less stately, zigzags still elegant in their dormancy.

I wanted to be them. I wanted the uniform.

I wanted to be them. I wanted the uniform. But the closest I ever came was a hand-me-down from my oldest girl cousin. It was a white and light blue check button-down dress with a tie waist, a cast-off from her regular wardrobe. If anything, it looked more grunge-inspired than school uniform—after all, it was 1995. But still, it was the best I could do. With no authority figure forcing me to wear it every day, I still put it on as often as I could. At least once a week, I arrived at my public elementary school in clean, intersecting lines: my own personal uniform.

Most people can vaguely identify plaid as originating from Scottish tartans, but I was surprised to find out that the pattern is over three thousand years old. The earliest example was found with human remains in a desert in China, though DNA tests later confirmed the man’s Scottish heritage. Researchers have also discovered that tartans were historically used to identify one’s hometown. Similar to the way my cousins might spot their classmates out and about after school by their uniforms, Scots strategically wore plaid patterns to indicate their region. Weavers used the local vegetable dyes available to them, and in remote parts of Scotland, most residents went to the same weaver. Dark threads dyed with regional tree bark could intersect lighter threads tinged with regional berries, creating a truly unique and local fabric.

With modern synthetic dyes offering infinite color permutations, a plaid pattern can be designed with extreme specificity. To this day, Scottish tartans are recognized as family symbols, and, for a price, anyone can register their pattern with the Scottish Register of Tartans. Doing so confirms that a tartan meets the criteria outlined in the Scottish Register of Tartans Act of 2008, and it provides evidence of the creation and date of the design. It also prevents future applicants from registering the design as their own. Beyond that, it’s mostly a symbolic practice—it does not trigger copyright protection, and a person cannot sue a clothing company for using their registered plaid design. Even so, I deeply understand its appeal. It can feel amazing to belong to something. And if there isn’t already a space where you belong, £70 doesn’t seem that steep for a pattern you can call your own.

As I got older, I grew to respect plaid not just for its connection to my cousins, but for its timelessness and ubiquity. In a divided world, it seemed a uniting force. At my high school, the punk rockers often showed up in plaid skirts or pants with Converse All-Stars. They sported Easter-egg-colored hair, stuck rows of safety pins through the straps of their backpacks, and seemed to have an endless supply of red and black plaid. Vivienne Westwood, who died in December 2022 at eighty-one, is often credited with the association of plaid with punk rock. She and her husband Malcolm McLaren outfitted Johnny Rotten of the Sex Pistols, and their shop in London (at one point called SEX) was a known hangout for many of the British punk movement greats. Taking the revered tartan and shredding it, ripping it, doing something “punk rock” to it, was an obvious middle finger to the establishment. When the Sex Pistols’ “God Save the Queen” was banned from British radio, Westwood’s status as a punk icon only ascended further. I didn’t know any of this back in high school, and I don’t think the punk kids did either—but a lot of them nonetheless wore Sex Pistols T-shirts because whether you knew the history or not, sex was a fun thing to invoke at school. It implied you were having it. (I wasn’t.)

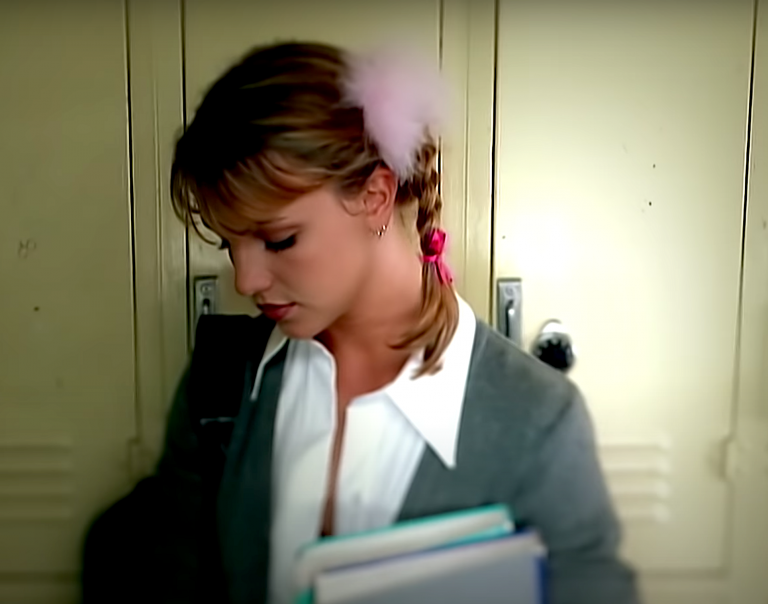

On the other hand, my preppy classmates were equally inspired by their own plaid-clad glamor icons. They wore it as long-sleeve button-downs from Abercrombie and American Eagle, no doubt finding confidence in the pattern after watching Clueless with their older sisters. Cher and Dionne look unstoppable in their matching plaid sets, even with mundane lockers and mundane people behind them.

While I wasn’t friendless, I didn’t fit in—but plaid did. And with its help, I eventually figured out I didn’t need to.

As for me, I felt confused by the social hierarchy of my high school. I was too much of a try-hard to be punk and too eccentric to be popular. The preppy kids were nice to my face but laughed at me behind my back. The punk kids, who I earnestly admired, laughed at me (to my face) and called me a poser. While I wasn’t friendless, I didn’t fit in—but plaid did. And, with its help, I eventually figured out I didn’t need to. By living in neither world, I could live in both.

My sophomore year, I went to the thrift store and purchased three old-school wool skirts. They looked similar and they were all my size, so it’s likely that they all came from the same (possibly deceased) person. My favorite featured a turquoise, black, and navy plaid pattern. Though it was decades old, I felt timeless and powerful in it. I could be disliked, I could be taken unseriously, but I simply could not be fucked with when I was in plaid.

By my junior year, despite my parents’ wishes, I had declared myself a writer and signed up for all of the writing electives, including journalism. The week before school started, I found a black-and white-houndstooth blazer at the mall and thought: this is it. This is the blazer I would wear to smile at adults and get an A, but then turn my back and write a story that upended everything. Full now of blazered confidence, I set out to do just that.

There is, in fact, some science behind the way I felt in high school. In 2015, a research paper in Social Psychological and Personality Science revealed a real connection between “dressing for success” and performance on cognitive tests. In studies, participants who wore formal clothing exhibited advanced processing skills, which researchers attributed to “felt power”—i.e., the well-dressed superstars felt powerful in their outfits. More humorously, in an earlier study called “The Swimsuit Becomes Us All,” people performed worse, across the board, on math tests while wearing a swimsuit than while wearing a sweater. The alternative to my blazer certainly wasn’t anything like a swimsuit. But still, I saw plaid as an alternative to vulnerable objectification. I was covered up and protected in plaid armor. Instead of curves, I projected myself to the world in straight lines and right angles.

Dressing the part, I actually began to feel smarter. In the spring of my junior year, I tagged along with friends on their college visits. One school—an enthusiastic favorite of my parents and school counselor for its attainability (given my modest test scores)—boasted about its cutting-edge technology as I sat in a computer chair in a decidedly twenty-first-century room. Out on the lawn, the unofficial uniform seemed to be black North Face jackets, jeans, and Ugg boots. Girls tucked their straightened hair behind their ears, and checked their reflections in brand-new buildings with floor-to-ceiling windows.

“Yeah, no,” I thought, praying my writing sample would somehow make up for what my SAT lacked. I wanted old. I wanted historic. I wanted my professor to be a guy on his deathbed with patches on his elbows, and I didn’t want him to know how to email. I wanted to read something and write all over the margins, clad in my studious plaid. I wanted to fall in love with someone’s brain. I didn’t care if my college lover was ugly. In fact, it would be better if they were.

What I wanted was to go to the most revered public school in my state, the one referred to as a “public Ivy,” the most college-y college my family could afford. And by some sort of divine intervention, I was accepted.

The school was founded by a Founding Father, and, at my orientation, students and faculty referred to him frequently in conversation with a cutesy nickname, like he was an old friend. I was full of outsized expectations. I made a playlist called “collegiate,” and it was as lush as a quad lawn (and as stuffy as a columned portico). Against a soundtrack of Ben Folds Five’s “Philosophy” and Death Cab for Cutie’s “Scientist Studies,” I packed my trio of plaid wool skirts and a black and turquoise herringbone coat. When I closed my eyes, I saw myself as stately, like a senator. Future me was thumbing through a centuries-old book for textual evidence and raising her hand at exactly the right time.

Unsurprisingly, I was about to be knocked on my ass.

At Commencement, the Dean of Students proudly declared that our first-year class had a record number of perfect 1600s. I looked around and tried to find these perfect people, but all I saw were Rainbow flip flops. It didn’t matter, though. The perfect scorers presented themselves to me one by one over the next four years, pretending their 1600s were an embarrassing secret while casually working it into conversation.

Every single person I met seemed to not only be smarter than me, but also to take college more seriously than me. I started pulling all-nighters in the library just because it was what all my friends were doing. I spent all of my Flex Dollars on saccharine cans of Starbucks Doubleshots. My ugly lover was nowhere to be found. My dreams of chatting on the quad about philosophy disappeared in the smoke of references I didn’t get and vocabulary I didn’t know. But people did seem to appreciate one thing about me: I was always down for a party.

The college me wasn’t the plaid-infused sophisticate I had imagined, but she was my best option at the time, so I embraced her. “Who wants to go out?” I’d say, popping my head into my suitemate’s rooms on a Thursday. I was extremely persistent in my pursuit of partying. I’d troll random strangers’ Facebook events and wander around fratty neighborhoods until I heard music. If there was a place in town where people were sitting outside on a dirty couch drinking Natty Light, I was there.

In my new setting, my precious high-waisted plaid skirt just didn’t feel like my style anymore. I cut off the top and gave it a lower waist, folding it over and hemming it into a miniskirt. With a small strip of leftover fabric, I made an asymmetrical epaulet across the top, traversing my hip line, and fastened it with a big wooden button. It was my fantasy collegiate experience repurposed to fit reality. I wore it with a sheer black off-the-shoulder top, hot pink bra straps showing. Tall black boots with buckles and a side ponytail completed my look. When I walked into rooms, I heard The Strokes’ Julian Casablancas singing: “Tell us a story, I know you’re not boring.”

The pattern I had looked to for strength and confidence as a child had become something else entirely.

I had come a long way from where it all started. The pattern I had looked to for strength and confidence as a child had become something else entirely. But in its own way, plaid continued to instill confidence. On a loom of inferiority, I still found a way to weave an unapologetic version of myself. I’ll always picture college me with a hand on her plaid-covered hip, head cocked to the side as some supposed genius flirted with me and my group of friends.

But even with my newfound miniskirted bravado, imposter syndrome weighed heavily in the back of my mind. As I leaned cooly on the edge of beer pong tables, I still feared someone from my past would expose me at any minute as a fraudulent loser. Exactly eight other kids from my high school attended my college, and I avoided them all like an 8 AM class. At one point, against my will, an almost-valedictorian who proudly broke curves back in our AP days ended up at a house party I was hosting. He raided our top drawer for aluminum foil, which he fashioned around his front teeth in the style of Lil Wayne. In retrospect, he was probably worried about the same exact thing I was, and I granted him no mercy. As soon as he left, I delighted in telling my housemates that he was the biggest dork in my graduating class.

Over time, my nighttime persona began to inform my daytime one as well. None of it went the way I’d expected, but with each passing semester, I understood my worth a little better. A 1600 showed the potential of a sixteen-year-old, but then what? There were other things I had to offer this world. Better things. I could raise my hand without fear and articulate a point more clearly than anyone in the room. In group projects, I was always the one with a plan. More intelligent people could wax poetic about a topic, but they often never did anything beyond that. I could concede that I didn’t know everything—it was the ability to lead, follow through, and finish that helped my professors view me as a strong thread, a standout thread, someone preventing the class from unraveling.

By junior year, the stack of books on my desk grew taller, sticky notes protruding from the sides. My favorite thing about the English building became the circle of smokers gathered outside it, freezing in their flannels, desperately inhaling toxic fumes. Their self-seriousness was something I relished. These were my people. We read and wrote and revised until we tore our hair out. We did it in our signature plaid. Inside that building, we intersected for a moment in time, weaving an earnest new pattern before going our separate ways.

We intersected for a moment in time, weaving an earnest new pattern before going our separate ways.

My childhood dreams of private school never came to fruition, but when I was twenty-two, I finally did enter those halls I’d spent so long imagining—as a teacher. I was aware of how absurdly young I looked, and even though I was teaching English to small classes of supposedly well-mannered twelve-year-olds, I feared they’d chew me up and spit me out. Still, I arrived on the first day of my first-ever teaching gig armed with a new haircut and a buffalo check button-down dress. The moment was immortalized in the staff ID hanging around my neck, the plastic still fresh and shiny from the printer.

In four lines of four, the uniformed students sat up straight, not only wearing plaid but for the moment, being plaid. I looked out my new classroom window into a beautiful courtyard, at once catching my reflection and my breath.

The intersecting lines of my dress gave me an orderly sense of calm. It was strong enough that when I said “Hello students, I’m your new English teacher,” I believed it.