I want to tell you a story:

Years ago, when my son was in preschool, I found myself in the human resources of big Harry Potter rich publishing house. I’d crossed the bridge from the New Jersey suburbs we’d found ourselves in. At the time, my husband and I were renting the top floor of a house in one of the toniest suburbs in the county. I didn’t have health insurance, but my husband and children did—through my husband’s home country. We’d just come from there, flown overseas, where things had been easier and cheaper. Childcare was subsidized and my son was happy and I was researching my first novel. But my husband’s green card had been denied and we were broke.

It goes without saying—the need for money is why one works.

To save money a friend of ours lived in the dining room and we had one car. In this tony suburb full of backyard structures and moms who lived in their perfectly manicured fiefdoms, where the only people in the streets were lawn care workers, we stuck out. I didn’t have a Gucci bag. Our car was not German. The roommate in our dining room gave everyone pause. Even if staying at home had been my thing—and it wasn’t—we didn’t have the money to do the things other stay at home moms did. For my son there were no camps, no mommy and me, no enrichment activities like the ones the kids around us took advantage of. I didn’t have money for pilates or yoga or Botox. We didn’t even have money for a proper flat for just the three of us. It was time to I went back to work.

The HR person scrutinized my resume. She asked why I’d changed jobs so frequently, not staying more than a year in any one publishing job. Because I needed to make more money, I told her. I almost rolled my eyes. She knew as well as anyone how low the publishing salaries were. Her eyes narrowed: Are you only interested in the money? My face flushed. Of course I was interested in the money. It goes without saying—the need for money is why one works. I told her that I’d gotten into publishing because of my love of books and the industry. Publishing had been my first real job, my only real job, I told her. I’d taken a few years off to have my son and we’d moved overseas so we’d have family help. But now I was back and I wanted to work.

I pushed aside washing machines at the laundromat for stray quarters.

I didn’t get the job, which was for the best, financially speaking. I’d done the math. My pay would hardly cover the child care costs and travel into the city. In the end, I left publishing. I took a job close to home where I worked as a nurse recruiter. My hours were flexible and no one cared that I hadn’t worked in a couple of years. I made commission. I talked to nurses all day and I did this until my daughter was born. There I was never shamed for working because I needed money.

When I started out in New York City publishing I made 19k a year, twenty-five years ago. This was a standard salary for editorial assistants and here’s a fact that won’t shock you—it wasn’t a living wage, even then. During that period, I lost my apartment. I squatted in an abandoned building in an apartment that was open to all who wished to enter. I starved. My mother had offered to send me a plane ticket home but refused to help me stay—I decided on my own to do so.

I had one room with a door I could lock. I showered at the Y. There were weeks before my next paycheck where I lived off the dry oatmeal in the office kitchen, learned to order soup and ask for extra bread on dates. I never passed a payphone without checking the coin release for abandoned change. I pushed aside washing machines at the laundromat for stray quarters so I could afford a bagel, a phone call, a subway ride. When a man at a street fair asked me to be a call girl I had a big long think on it before I finally said no.

When my mother had stage four cancer when I was 10, we were not financially ruined. Her union job protected her.

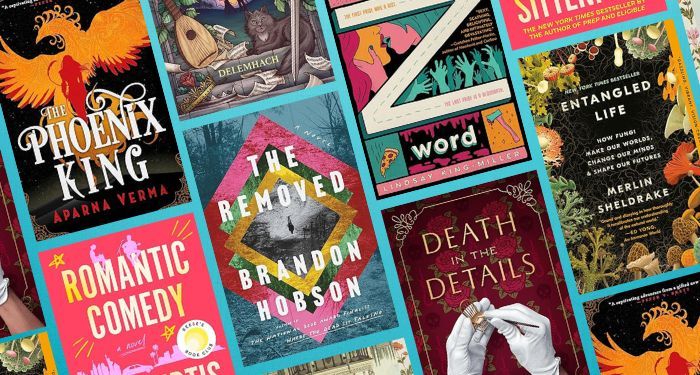

I wanted to live in New York, wanted to work in publishing. I wanted to be a writer. I lived close to the bone, and I had no social life. Getting cheated by a cashier meant the difference between eating a hot dog off the street or starving that night. After some time, I left that publishing house for another and made a few thousand more. But when I left that first job, I also left editorial acquisitions—the sort of job that decides what books get published. I worked for managing ed, copy editing those already acquired manuscripts. Managing editorial departments, production departments, publicity—these jobs generally pay more than acquisitions—which are generally more prestigious and which might explain the sorts of books that we’ve always seen published, continuing to get published. With the extra money, I got out of my squat. I had managed to save the prerequisite first and last month’s rent and some extra money for a bit of furniture, and moved to a room downtown. This was the late 90s when there were still cheap rooms to be had in Manhattan. Then I jumped off to a dotcom that was short lived, but where I finally was paid a living wage. My last boss in publishing asked me how much I would make at the dot com and when I told her, she laughed. “You wouldn’t make that in ten years here,” she said. She might have laughed, but to me it was serious.

The big five publishing houses are owned by huge conglomerate companies. Harper Collins, recently on strike, is owned by News Corp, Rupert Murdoch’s company. They pay these wages because they have always paid these wages—not because they can’t afford to pay better. Publishing is the sort of job that wealthy white people historically did, no one else need apply. Coming from greater Detroit (and not the parts that typically wound up in places like New York City), I had not understood any of this. If I had, I’m not sure I would have come at all. I was willing to pay the enormous price of moving to New York City because I’d been too ignorant to understand the price that would be exacted of me.

My father and mother had followed their calling. Both believed there was something noble in their professions. My father was a reporter who refused any editor or management position he was promoted to. His union job was safe and he was a union man until he retired. My mom was a Detroit public school teacher. When my mother had stage four cancer when I was 10, we were not financially ruined. Her union job protected her. Moving to New York City I hadn’t realized that my dream job was a job for people who had trust funds, or, at the very least, a parent or spouse who helped with rent or paid off credit cards. Not for people with parents who would not, or could not, help them.

…since those years, every interaction I’ve had in the publishing world has reminded me of the difficulties I faced.

Here is a fact: if a person cannot make a living wage in their job, even living as frugally and close to the bone as I was, then the wage is too low. It’s unconscionable that publishing—especially those with big umbrella corporations like News Corp or the late Sumner Redstone’s company, Paramount Global, continues to pay their publishing employees so little. When I looked at starting salaries of publishing positions today, I was shocked to see they are exactly as low now as they were then, adjusted for inflation. Only now things are much harder. I lived without cable television or a cell phone back then. It would be impossible, especially during the past three years of remote pandemic working, for anyone to live without internet.

It’s especially unconscionable in light of what we know now—and let’s be real, we knew it then—that low wages keep out those with less means, and those from marginalized communities, in particular. This kind of gate-keeping is deeply problematic, and the exact opposite of what publishing should be doing.

Ever an optimist, I believe publishing can change. It’s heartening to watch social media support for these young, underpaid workers. There was no such thing all those years back when I was broke and struggling. We were told that all editorial assistants had it hard; we were told we were paying our dues. And we were told that it was necessary.

I’d love it if we left that line of thought behind. No one deserves to be underpaid and unsupported. I am now on the other side of the publishing equation, as an author. My life is far more comfortable than it was then thanks to circumstances that had nothing at all to do with the publishing industry. But since those years, every interaction I’ve had in the publishing world has reminded me of the difficulties I faced. I wouldn’t wish those difficulties on anyone. Junior publishing has banded together because the low salaries and workloads were untenable and because rather than leave the industry, as I and so many others did, they’re organizing unions and spreading the word. One publishing house has settled with its striking workers and a few others have committed to raising starting salaries. These are small, but good, steps.

But here is another fact:

People work for money. They go to jobs in order to get paid. Unless they are wealthy, our society demands this from them. A passion alone for literature and books does not pay the rent. It might be easy for publishing executives to forget that reality once they’ve reached a certain income bracket, but it makes it no less a reality. I sat in the HR department of that publishing house because my family needed money, not because I loved books so much. I took that nurse recruiting job because my family needed that money. It goes without saying that nearly everyone in publishing loves books—it should also go without saying that everyone in publishing deserves a living wage.