My earliest memory is writing my name in purple crayon. Again and again I wrote it, kneeling on the floor with some scraps of paper. I remember the moment so vividly, not just for the writing itself, but the feeling of certainty. I knew damn well that this weirdly wonderful happening of word-on-paper was right somehow; it was significant, it made sense. It was intuitive. I was alone, and all I was doing was being myself, having fun, playing. An early time in life when nothing and no one had yet swept in and told me that what I was doing was wrong, or that I should BE anything other than what I was. The sense of self we are all born with before life comes along and shakes it up. I hadn’t yet been told to, ‘Get my head out of the clouds.’ Right and wrong were lessons about the world around me and how I worked in it; they had yet to creep into my belly, dictating what aspects of myself were permissible, and which were not. Autism was not a thing; I was the shy, frightened type. I started to write rhymes – deep in a wood, down in a hole, lived a little lonely mole – and enjoyed the smiley stickers and pats on the head from my teachers.

No one came out as gay in the nineties when I was in school.

Shame creeps in when we are made to feel like crap for being ourselves, an accrued sinking, deep-cringe feeling of something fundamentally wrong with us. In high school, I began to hear the smirks or frustrated sighs when I said, ‘I want to be a writer.’ My head was stubbornly stuck in those clouds; so began my angsty poetry phase, neatly colliding with puberty. While I had no idea what was going on with all these bodily changes and urges, I was well aware of my headspace growing ever stormy; it was what would become the dark in my dark comedy, from a view of the world that is both Stephen King and Beatrix Potter. I latched onto the term ‘bisexual’ in an unspoken and uncertain way, flinging words with endless, skilless energy onto the page. By university, and in true cliché writer fashion, I had taken to wine and set off as cheery and naïve as Dick Whittington, determined to get a top degree in Fitting In.

Be fun-loving, be clever, be cool, and for the love of God, be straight.

No one came out as gay in the nineties when I was in school. With frizzy hair and wonky teeth and skinny legs, I had wanted only to be invisible and blend in. Now with cropped hair and straightened teeth and hidden legs, college seemed the perfect place for reinvention, simultaneously exploring, and hiding, myself.

I studied English Literature, had successfully progressed from angsty poetry to angsty first novel. In the emotionally safe, booze-addled world of college bars and parties, where everything could be brushed off as drunkenness, my sexuality began to peer out. Explore, and hide. I knew I wasn’t straight but was scared to think I might be gay, just as I wanted to write but was scared of whatever it was I had to say. Neither my behavior nor my writing were good, and I finished university with a (to be honest, miraculous) 2:1, a few hundred pages of drivel, and a deep sense of being utterly lost and alone. Being myself felt wrong, being someone else hadn’t worked, so I wasn’t sure who or what to be next. In the end, I returned to my home town, to have one of my (oh so many) ‘fresh starts.’ I stopped writing, got a boyfriend, got a job in HR, and for several years led a life in blissful, booze-fueled numbness.

I really thought I was done with writing. After all, as I had heard time and time again, only deluded idiots wanted to be writers, the same deluded idiots that wanted to be dancers or singers or footballers. The world I inhabited was the sort that regarded artistic, creative, unusual lives with patronizing suspicion, unless you had a contract with Manchester United or The Royal Ballet, in which case you were regarded with patronizing envy. Dream-chasing was something children, geniuses, and fools did. Us – normal people – were not supposed to pursue dreams, we were supposed to pursue promotions and pay raises. After all, I was not a child nor a genius, and no one wants to be a fool. In fact, being foolish and being ridiculed were what I feared most.

There seemed, then, to be so much fear around foolishness, fear of embarrassing oneself, that shame was used as a sort of vaccination, a preventative measure. If you were shamed into hiding your sexuality for example, well, at least it saved you, and your family, from being bullied or mocked. This approach was wonderfully effective in many ways. Shamed into ditching the dream and getting a dull office job? At least you won’t have the humiliation of answering questions about your twentieth rejection letter. There was even a neat reward at the end: When you had the house and the cars and the holidays, and your life looked like everyone else’s, nobody would ask you pesky questions about that old dream anymore. That would be long forgotten. You’d get so good at the act, you’d almost believe it yourself, and people at the barbecue would say how far you’d come, basking in the reassurance that we must all have gotten it right somehow, living as we do.

Except, it doesn’t work like that. It can’t. We are who we are, and a dream is never forgotten, it is only abandoned. It’s as simple as that. It will rear its green head when you read, or watch the game, or see the ballet. It gnaws at you in constant reminder that it is there, unattended to, like a dying thing in need of attention. Your intuition, foolish or not, will not be silenced.

In one short week, my relationship and career and home life fell apart.

We are who we are, and a dream is never forgotten, it is only abandoned.

I was twenty eight. I stood by the single bed in the spare room of my Dads’ house and looked at all the books – my books, exercise books, notebooks, filled with scribbles and stories and poems – which I had just, again, unpacked, and I knew that this had to be it. It had to be writing. It was the first feeling of giving in. Not bravery, not a fist in the air as I cried, ‘I shall do this thing!’ but that feeling of failing a fight. I got a job in a factory, and I started to write again, this time with the acceptance that publication was unlikely but that I would write regardless, forever, because I couldn’t not do it anymore. Publication was still a dream to me, but writing was a necessity. And I recognized a very old feeling, of something just being right.

Sexuality was a different issue altogether, partly because I still saw it as an issue. I wasn’t yet ready to stop questioning and denying, and despite now knowing what a ‘right’ feeling was like, I still didn’t allow this when it came to love and intimacy. I sometimes read about people coming out in huge, wild, wonderful ways, like a burst dam, and I applaud them, almost enviously. Mine wasn’t like that; many people’s coming out stories aren’t like that—more a trickle than burst dam, drying up occasionally, or filtering off all over the place.

In parts of my twenties and thirties I sort of explored my sexuality and sort of said I was bisexual and said I sort of wrote – a bit, but nothing much, just silly stories – but I was still too afraid and embarrassed to own any of it. By thirty I was married, in a polyamorous relationship, where behind closed doors I explored and wrote and grew, quietly.

We are not all flowers. Some of us are mushrooms.

My first novel was a heavy erotic thriller that took two years to complete and was rejected everywhere. ‘Too dark,’ everyone said. Funnily enough, one agent responded that she liked it but, ‘…it doesn’t seem to know what it is’, which was bang on in more ways than one. The next book was a heavy psychological drama that took three years and landed me my wonderful agent, but also remained, and still remains, unpublished. ‘Too dark,’ everyone said again. Then I had a little breakdown – divorce, house moves, job moves, confusion quelled by pinot grigio, another fresh start – and wrote another book, which was also a heavy psychological drama, and also too dark. And I remember hearing this feedback, which I had heard so many times before, and suddenly I gave up.

I big fat ugly gave up.

I fuck-this-and-fuck-them-and-fuck-life gave up.

I hadn’t realized it, but I was still acting; even on the page, I was acting. I was so sure no one would want to really see or hear me, so I had habitually always edited out the zany, the silly, the weird, the gay, from my writing, convinced that these were all the undesirable and wrong parts of me. I thought they were the embarrassing bits, I was ashamed of them, and I thought I had to write seriously to be taken seriously. But then, eleven years after quitting that HR job, after everything had fallen apart several times over, and after enough rejections that the word had lost all meaning (they really do just become good liners for a litter tray) I just abso-fucking-lutely gave up. Three novels, writing for over a decade. I just felt done with it.

But, of course, I wasn’t.

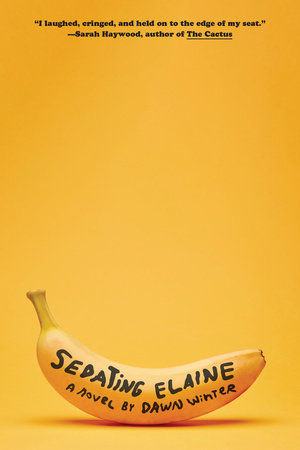

I had for months been writing a joke of a short story for a friend who was going through a break up, something silly to make her smile. Whenever I was on a break from my ‘serious’ writing, I would play with it. It was like a game, just a laugh, I didn’t take it seriously. In this moment of giving up, in a sort of hopeless ‘what about this then?’ I sent the first few chapters to my agent, who replied telling me to ‘just keep going.’ Six weeks in the first lockdown, I just wrote, like I had never written before. From absolutely ditching the effort to be anything – to be better or different or right – I wrote and wrote and wrote, so fast my fingers barely kept up. It was eventually titled Sedating Elaine, and off it went to the publishers.

I didn’t really believe that this would be any different from the times before. You come to expect your normal, which was, in my case, positive murmurings but ultimately rejections. That said, there is a tiny entry in my diary on 22nd October 2020 that reads, ‘I am almost afraid to write these words, but I have a feeling that this one may have made it.’ Still, I tried not to think about it.

I hadn’t realized it, but I was still acting; even on the page, I was acting.

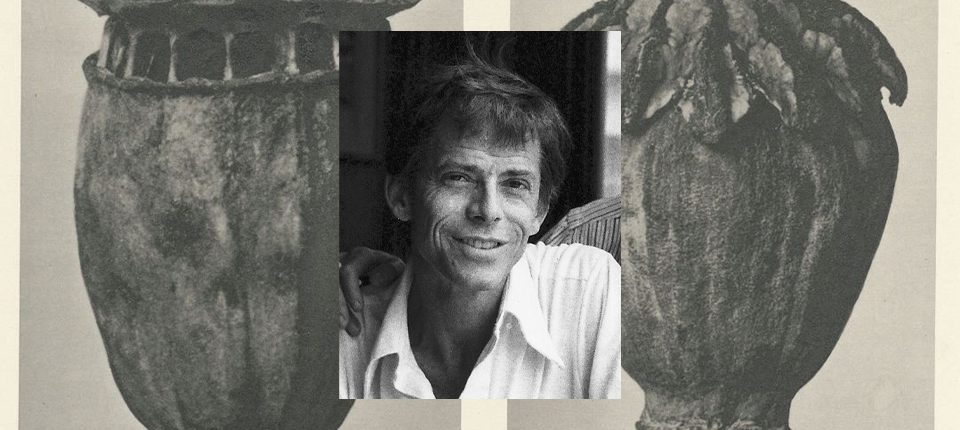

But then, it happened. Sedating Elaine sold to Knopf on a pre-empt within a fortnight, the TV rights went to ABC shortly after, and I stood around in a stunned daze, finally with a book deal, from the most ridiculous book I had ever written.

That this book – this book! The book I was writing as a joke! – should be the one to make it, baffled me to say the least. I had spent years on my previous books, I’d agonized over them; it seemed ever so strange that the one I’d just sat down and written without really thinking about, should be the one to make it. It hadn’t been difficult, it hadn’t been torturous, it had been a laugh, a breeze. It didn’t make any sense at all.

That was, until I remembered. I remembered what it felt like. What writing it had felt like.

It felt like purple crayon.

It felt like doing something freely, without any shame or judgement. It was a release of unapologetic authenticity, and that is a valve that only flows one way. And I was out in more ways than one, when people who had always assumed I was straight — some who had known me all my life — read it, and it fell into place; I love who I love, it needs no scrutiny nor explanation, because intuition guides me there and as such is always right, regardless of gender or labels. It’s about time; I turn forty this year, and I have just arrived. Purple crayons and make-believe, I’ll shove my head in the clouds and be damned if anyone can wrench me down. Because this is just as it should be, just as writing should be; fun, easy, playtime. Write from the same place in you that built sandcastles and dug mud holes and played the saucepans with two wooden spoons. It will never be real if it is stifled by constrictions and rules and doubt. Ditch all of that crap, and play to your uniqueness.

Sedating Elaine is out now. And so am I.