In 1993, I published my first decent story in a literary journal and a few months later received a letter from an agent whose name I recognized. I’d written short stories in college classes, sent them off, and typically the only thing that came back was a rejection, housed in the self-addressed-stamped envelope I’d sent with the story, my own handwriting preparing me for the paper inside that said thanks, no or we liked this, but.

The agent letter was a surprise, and I was buoyed by it for days. The letter went something like this, “I enjoyed your short story. I’d be interested in seeing more of your work. Do you have a novel?” It felt great to be approached. It was flattering. But the answer was no: I didn’t have a novel.

A few years later, I received another agent letter after another story publication. A few years after that, an email. The notes all said some version of “I liked your short story. But do you have a novel?”

I’d heard from my graduate school creative writing teachers, who taught us only to read and write short stories, that a fiction writer’s final form was novelist, or at least, they said, that was the publishing industry’s core belief. The books that sold well, the books editors at big publishing houses wanted to acquire, were novels. Collections could be published, sure, but they were afterthoughts or add-ons.

Whenever it came up, the “do you have a novel” question made me a little indignant. I thought it was like telling someone to use their eyes for eating. Novels use words and sentences, obviously, just like short stories, but they require a different skillset, as well as a lot of attributes, like patience and a good memory and discipline, that I—first as a 20-something who just wanted to write poem fragments on my forearms and listen to Pavement, and later as a parent, shellacked with two smallish kids and a full-time job—did not have. If I could write even a third of a short story over a few weeks, it felt like a win.

The notes all said some version of “I liked your short story. But do you have a novel?”

When my kids were more self-sufficient and I found myself with actual pockets of time to write and submit, I started getting wildly, embarrassingly jealous of every Publisher’s Marketplace announcement I saw. More egalitarian and generous writers would Tweet about how “there’s enough success for everyone, there’s plenty to go around,” but I, then in my 40s, felt like maybe there wasn’t. Maybe short story writers, all of us vying to win the same few small-press collection contests that ran each year, were doomed to not have book deals. I decided to try to feel content about publishing individual stories in literary magazines and pushed aside the idea of a book.

The next time an agent emailed me was 2020, and it was the same line as ever. “Do you have a novel?” No. “I really cannot sell a collection on its own.” Okay, I understand. “Do you plan to write a novel?” I guess. Maybe?

I signed with the agent, which was a leap of faith more for her than for me. I started trying to expand a short story I’d published, to build it somehow into a novel. In most ways, it was like trying to make a bathmat work as a rug in a room the size of a ballroom. Still, I wrote early in the morning, on weekend days, while waiting for doctor’s appointments, on all-hands meetings. I remember even feeling a little bit hopeful, like, “Maybe I’m doing it, maybe I’m really writing a novel, finally,” like this magic land, unenterable for twenty plus years, was opening to me.

In the end, my draft was more of a loose assemblage of stories. The plottier parts that lurched each chapter forward, the parts that made it a possible novel, weren’t working. When I expressed self-doubt to my agent, she asked me, more than once, if this was “the book [I wanted] to send into the world,” which felt pretty jagged. I remember thinking, Well, the book I want to send into the world is my short story collection. Maybe I even said it out loud.

We went “on sub,” which is the silly sport-game-sounding name for flinging your book out to a selected group of editors, followed by the brutal process of checking email all the time, being mad at anyone who emails you who isn’t your agent, and (in my case) almost always getting bad news. We sent the book out to 18 editors, and over the course of a few months, we got many nice rejections, paragraph-length notes my agent told me were encouraging and that I should feel good about, and even one call with an editor who liked the book that ultimately resulted in months of ghosting and no book deal.

The process was flattening. People wanted “propulsion,” and I was focused on sentences and moments. I liked the quiet pockets I was able to build into short stories but that felt harder to make work in a novel.

In a stupid fit of “now what?” I frantically, in a few months, wrote a whole other novel. The agent hated it, which stung, but it was likely hate-worthy.

I liked the quiet pockets I was able to build into short stories but that felt harder to make work in a novel.

How did I spend the pandemic? I speed-wrote two novels, only to realize I am not a novelist, or at least not yet, and market trends, traditional publishing’s seeming demands for books that rapid-cycled you from beginning to end in one sitting, weren’t going to make me one.

In summer 2022, I parted ways amicably with my agent and returned to story writing. She told me if I started working on another novel project, she’d take a look. I didn’t fault her. Agents have been told collections don’t sell. So many of them have to deal with the industry realities of looking for plot-heavy books. This isn’t to say there aren’t brilliant and successful poetic, experimental, quiet novels – there obviously are. But if you’ve queried an agent lately, you know: propulsion and plot are king.

I disassembled the second novel draft and built some short stories from the parts, then wrote some new stories, too. I understood stories and loved how within one I could focus intensely, think about every word, and I could experiment without worrying about staying on a path of forward momentum. I revamped my short story collection, sandwiched in some new stories, moved things around, took out the flash fiction.

This, I thought, feels like the book I want to send out into the world.

I submitted it to the same few indie presses and university contests where I’d sent earlier versions of a collection and had been rejected more than once. At this point, only a few of the stories were the same. What the hell, I thought. I was 54 and had gotten my first “but do you have a novel?” agent letter thirty years earlier.

And then I waited. Items in my Submittable queue changed from Received to In Progress.

In August, I moved my daughter into her first dorm room in a tall building, and I thought, simplistically probably, about how the dorm, each floor, with each room another person, style, story, was a collection, and how so many things in the world were more an assemblage of disparate parts than a mellifluous whole. My daughter, who is also a writer, said it didn’t make sense for people to be so weird about short stories. Why was publishing so opposed to short fiction, when the world seemed to want and love short-form everything else?

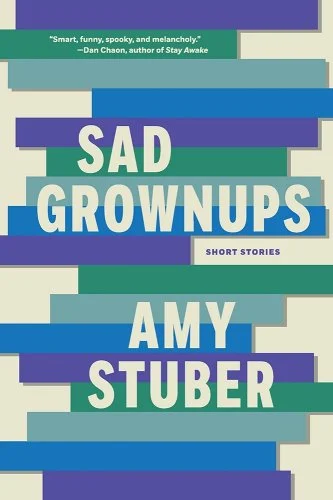

In September, a few weeks after leaving my daughter in New York, in my haze of sadness that was like an anvil hitting me repeatedly and saying you fucking fool why did you help make a person who is designed to leave you, I got an email from one of the small presses. I saw the re: ____ subject line, and I braced myself for the rejection those emails usually are. Instead, it was a nice editor I’d corresponded with a few years before, telling me they wanted to publish my collection.

I was so numbed by life that month, by all the accumulative sadnesses of being 50-something in a whirlpool of life change, that I wasn’t sure how to feel. But when I stood up from my computer to walk around the neighborhood and look at all the familiar things, so many of which had years of memories attached to them, each their own little story, I let myself feel happy. This wasn’t the novel. It wasn’t the Big 5. But it felt truer to the writer I wanted to be.

Small presses, less beholden to concerns over big sales, are able to publish collections and the kinds of books Big Publishing tells writers we shouldn’t bother making. For that, I’m grateful.

As is true of so many writers I know, some of my favorite texts are short stories. Each time I come upon a new collection in the library or in a bookstore, I get excited about the hive of situations and characters I’m about to dive into and the room for experimentation. It feels like so much possibility.

I remember hearing last year that a lot of traditionally published debut novels sell only in the hundreds of copies. The managing editor of the small press that accepted my collection told me something like, “During the life of the book, a good outcome would be selling 1000 copies.” A thousand sounded good. Better than the hundred of some novels. Big Fiction’s insistence on the novel as default is maybe a failure of marketing or the imagination about what a book can be and do.

Small presses are able to publish the kinds of books Big Publishing tells writers we shouldn’t bother making.

I’m trying again to write something that approaches a novel, but this time I’m letting myself lean into my tendencies and reminding myself that a novel does not require a traditional narrative arc, nor a set number of scenes and beats. So I’m trying a “novel in stories,” and I’m not writing it with some big splashy publication in mind. I’m writing it when and how I want to write it.

After an excerpt of the novel-in-stories project won an Honorable Mention in a contest, an agent I adore, a “dream agent,” messaged me and asked me if I had the full novel ready. I don’t, at least not yet. But when I do, I hope I’m able to pull together a whole made of small slices of the world pulsing together, a collection in its own way, that champions the short form while also feeling like a whole. To the industry, maybe it will even be considered a novel.

Is this just an essay about someone who wanted to and couldn’t sell a novel so now wants to champion the short story? Maybe a little. But, more, it’s about a circuitous path away from and back to the thing I actually enjoy writing, that the industry told me I shouldn’t do if I wanted to succeed.