“Boomerang” by Asha Dore

I was the worst mother in the world that Tuesday night when Maggie was two months old. She was exactly the weight—pounds and ounces—she’d been the moment she was born. I boiled water for Lise’s butter noodles and wore Maggie strapped to my chest in a baby wrap, the fabric stretchy, cornflower blue and dotted with spilled milk. The wrap smelled a bit sour. For over a week, I’d been dropping milk in Maggie’s tiny mouth every ten minutes, as many drops as she’d swallow. The rest slid down her chin and neck and onto the wrap. I slept in ten minute bursts so I could feed her when the timer went off.

Still, she was starving, shrinking.

I tracked the events that led me here, a week before my twenty sixth birthday, somehow a mother of two, somehow alone, carrying this hunger the way I had for my younger brother ten years before. Back then, my brother and I survived on expired burgers I’d swiped at the end of my McDonald’s shifts. Our mother ate the burgers with us some nights, in between disappearances into beach parties and weed and warm beer, habits she’d leaned into years before dad died.

Dad had always been the Sunday night dinner parent, the one who organized holidays and getaways to the river or beach camping or sneaking into the pool at the Holiday Inn. It made sense to me that when he died, all that ended. At holiday gatherings with our extended family, when a cousin came in loaded or an aunt brought over godawful oversalted gumbo, Dad said the same thing he said about Mom when she disappeared from our family or woke me up in the middle of the night to reload the dishwasher and stood behind me, wiping her eyes and asking what it meant to have a daughter who actually loved her mother and showed it. Dad cleaned up the mess the load cousins left or secretly dumped two thirds of the gumbo in the trash or woke up to Mom’s voice, stepped between me and Mom and the dishwasher, led me to bed, and sat on the foot of my bed reminding me to take deep breaths until my body relaxed enough to fall asleep.“Can’t blame someone for being bad at something they’ve never been good at,” he said.

I turned away from the boiling noodles, tipped Maggie’s head back, and set a drop of milk on her lips with a syringe. She moved her face around my chest, looking for milk. I set the syringe against my breast and into her mouth. She swallowed half a milliliter this time, letting the other half spill out of her mouth and onto the blue wrap. More pale stains. More wasted milk.

Dad had always been the Sunday night dinner parent, the one who organized holidays and getaways to the river.

I tickled the soles of Maggie’s feet until she perked up. The water made that hissing sound, that white noise, the pre-boil. I set three drops of milk in Maggie’s mouth at a time. She drank slowly, drop by drop. One more half of the syringe. “Take it slow,” the lactation consultant had told me. “She can burn calories if she spends too much energy swallowing. Babies swallow with their whole body.”

Lise chattered a couple rooms away, talking to herself in two-year-old syllables, real words mixed with leftover baby babble. She sounded happy. I dumped noodles into the boiling water. I reset the timer for Maggie’s feeds.

Ten more minutes.

I leaned against the counter and closed my eyes.

For over a week, I had been alone in the house with the girls, pacing, wearing Maggie, pacing, following Lise from room to room, pacing, feeding Maggie drops of milk. When Lise watched a movie or slept, I unpacked boxes. At night, I slept in ten minute increments, in between feeds.

Hurst’s job at the Navy ended a few weeks after Maggie was born. For three years, I believed the Navy was the problem, with its unrealistic demands and weird control tactics. The Navy had caused Hurst to disengage, to spend his minimal time off ignoring us. The day after Hurst was discharged, guys we hired in a U-haul followed us down to Florida. A few days after we arrived, Lise came down with a snotty, sneezing cold. It ran through the whole house. When Maggie got it, she was extra sleepy, not nursing for very long, milk falling out of the side of her mouth. My breasts stayed hard, never empty. I bought a baby scale and tracked Maggie’s weight gain. She took breaks from nursing to cough and sneeze and whimper.

Her weight didn’t change for three days. “She’s not growing,” I said to Hurst. He wanted to check. Maybe I misread the scale. Maybe I was overreacting. Maybe I incorrectly wrote down her weight from yesterday and the day before and the week before that.

I called pediatricians but couldn’t find an appointment. She didn’t grow. I went to the emergency room, waited for four hours. The doctors told me, “She’s got RSV. Day 5 is the worst, and that’s tomorrow. Go home.” I went home. I called lactation consultants. They told me how to hold her, to tip her, so she could breathe easier through her stuffed nose and nurse more effectively. They told me to buy a plastic sack with tiny silicone tubes. I pumped the milk left in my breasts after Maggie nursed. I put that milk in the plastic sack and wore it around my neck. The long, thin, silicone tubes went from the sack, through my bra strap. I taped them next to my nipple, threaded them into Maggie’s mouth while she nursed. As she did, I squeezed the sack so she could get more milk.

She didn’t grow.

I returned to the ER two days later. “I think she has failure to thrive,” I told the doctors and nurses. I told them she had vomited four types of formula, could only hold down breastmilk, and barely any at that. “She has a small jaw,” they said. They kept calling her a preemie, and I kept correcting them, “She was born a day after her due date. More than 40 weeks.”

Maybe I misread the scale. Maybe I was overreacting.

I told them my breasts felt full after she nursed. They told me she may be a slow grower. Is that even a thing? They told me I must have been wrong about her due date. I must have misread the scale over and over. They told me to go home, so I did. The next available appointment for a pediatrician was two weeks away. I called a private lactation consultant. I couldn’t afford to pay her to come help us, but she agreed to talk to me for fifteen minutes on the phone for free. “Feed her every ten minutes,” she said. “Use a spoon or a medicine dropper.”

“I have one of those plastic syringes from the Children’s Advil bottle. And the one milliliter things from the hospital.”

“If she’s growing, she’s eating,” the lactation consultant said. “Feed her as much as you can, as often as you can. Try every ten minutes until she starts to grow.” She explained the way babies can lose weight if they spend too much energy swallowing. “Receiving,” she said, “is all babies have to do. It’s up to us to teach them how to receive in a way that helps them.”

That’s how we all start, I thought. Receiving.

“This will be tiring,” she told me, one minute after the free fifteen minute consult ended. “Do whatever you can to take care of yourself until she starts to grow.”

At night, I slept for ten minute increments, in between Maggie’s drops. As I fell asleep for my small naps, I repeated sentences in my mind. She will wake up all the way. She will drink. She will swallow well. She will wake up all the way. She will swallow. She will survive.

I didn’t repeat those sentences when I fell asleep accidentally, leaning against the kitchen counter, that Tuesday night while the noodles boiled. I woke up to the BZZZZZZ of the timer and Lise saying, “Mommy?” Lise stood under the stove looking up at the pot, bubbling, steaming, hissing, her arm up, reaching toward it. “Bubbles!” she said.

“NO!” I said. “Oh no. No!”

I moved in between her and the stove, hearing my own voice like it was someone else’s, a single syllable, as it turned into a growl. Lise stepped backward, stunned. I shoved the pot to the back of the stove and sat down on the floor, slowly, pulling a pre-filled syringe from the counter on my way down. Lise crouched five feet away, her eyes wide. “I’m sorry,” I tried to say. Was I even saying real words? Was it still that growling? Lise froze in her crouch, a defensive animal, staring at me. Tears slammed out of her eyes, but she didn’t blink.

“I’m sorry,” I said. My voice sounded human again. I put drops of milk, carefully, in Maggie’s mouth, even though my shoulders shook. Maggie drank half a syringe. Then the other half. Stay down, I thought, like my command could keep the milk in her belly.

Lise crept toward me, and I dropped the syringe and held onto her. My shoulders kept shaking, but I didn’t cry, I wouldn’t. I wouldn’t put this tiny person in any kind of position to take care of me.

“I was scared. You’re safe.”

Words, but shaky. An attempt at the sing song voice the waldorf teachers told me would protect a toddler’s nervous system, the same nervous system I had just jacked the fuck up as I plowed Lise’s totally normal curiosity about the boiling bubbles into a small and scaryheartbreak. I smoothed her pale hair. “You’re safe.”

Lise froze in her crouch, a defensive animal, staring at me.

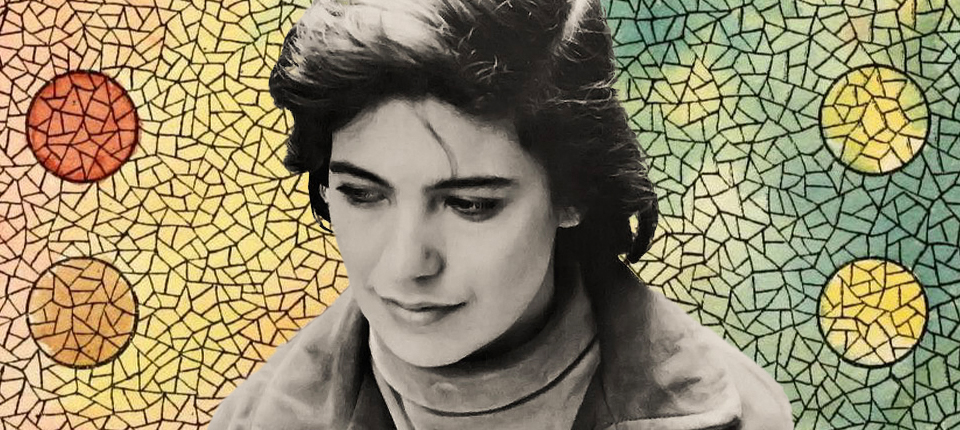

Shortly after Dad died, I found a zine in a local coffee shop about mad women in the attic. The writer had surrendered her children to the state, and she wrote about the mythological but widely unacknowledged belief that a woman’s value is comprehensively connected to her success at parenting, and of course some women scream and claw, retreating to the attic or setting the whole house on fire. The zine reinforced what I’d been hearing forever: that it’s not only unreasonable to expect my mom to act differently around us, but it was shitty to judge her for being unable to conform to the 1990s calm and predictable sitcom mother who could only really survive inside of the walls of an episode, a story written by someone else, directed, filmed, and edited to make the audience feel stressed or warm at exactly the right moments, to bring every conflict to redemption, to bring every potential despair to swift and satisfying resolution.

The night before I fell asleep leaning against the counter, Hurst went to work at an overnight security temp job and did not return home in the morning. He did not answer the phone. Four hours after Hurst should have arrived home, Cherry called me. “He’s here,” she said. “Sleeping, recovering.”

“From what?” I asked.

“It’s all so hard,” Cherry said.

I said, “Maggie’s grown a few ounces. I think the feeding schedule is working.” I paused. “Cherry,I need him to come home. I need to sleep.”

“He’s just not ready to be a father.”

I wanted to argue with her. I wanted to tell her but Hurst slept all day before his shift.

I wanted to tell her He’s been a father for almost three years.

I wanted to say, Put his ass on the phone right now.

I didn’t want to go there though. I didn’t want to let my low-class sailor mouth frustration show through. I didn’t want to command people, to tell them they weren’t loving me correctly. I said, “I really need to sleep.”

“You’re both working so hard,” Cherry said. “I’ll swing by tomorrow, bring you a treat.”

The next day, Cherry swung by. She held Maggie while I took a shower. I stood under the water for twenty minutes, as hot as I could get it. I put my face in it, sat on the floor, rested against the shower wall.

When I came out in a fresh t-shirt and shorts, my hair wet and stuck to my neck, Cherry handed me Maggie. All of the full syringes sat on the table, unused.

“We missed a feeding?”

“I was afraid to do it wrong,” she said, her eyebrows raised. She looked pitiful, concerned, truly concerned.

I glared at her, “It’s fine.” I showed her how to feed Maggie, making my voice as soft and sing song as I could, to protect her nervous system.

“I bought you a set of silverware,” she said. “It’s on the counter. Everything you might need. Expensive.”

I didn’t want to command people, to tell them they weren’t loving me correctly.

I strapped Maggie to my chest and walked into the kitchen, set the ten-minute timer, and stared at the silverware. Cherry gathered her things to leave, and I took five deep breaths.

“Thanks. It’s real nice,” I said. “When is Hurst coming home?”

“He needs a few days,” Cherry said. “Night shifts are so hard.”

I walked out, watched Cherry sort her things and move toward the front door.

“He’s a good father,” she said.

“Ok,” I said.

“A good man.”

“Right.”

“Most men would have left already, I mean really left. Two kids, and one of them…Men can’t handle it like we can.”

“Ok.”

“He wasn’t ready to be a father, you know. He didn’t know what he was in for.”

“Sure.”

“And I know you have trouble with your family. It sounded like your dad was a good person, but your mom…It’s hard to be the only grandparent around.”

“Yeah,” I said. “I bet that is really fucking hard.”

I walked past her without looking. I walked into my bedroom where Lise napped on a small toddler bed in the corner, where a noise machine played rain sounds, where I could sit and massage my hot, hard breasts, where I could seethe, where I would feel just a little bit less alone.

After nine days of the ten-minute feeds, my eyes blurred.

My vision went sideways.

Hurst had stopped by at some point, then returned to Cherry’s house to help her with some projects. “Her espresso machine, MWAH,” he said. He made a chef’s kiss in the air. He took a long shower, watched Tangled with Lise, then left.

I touched the walls while I walked to keep them vertical. I hadn’t yet unpacked the ice trays, and our belongings were a maze of half unpacked boxes. I filled random food storage containers and some of Lise’s plastic toys with water, froze it, and carried the ice to stay awake. I put the ice in my bra until it burned.

When I took my ten-minute naps, as I fell asleep, I told myself I will wake up in ten minutes I will wake up in ten minutes I will wake up in ten minutes she will survive.

Sometimes, I started to doze while I fed Maggie, a kind of darkness sliding across my eyes. I pinched my skin where it would hurt the most—my armpit, my ass, my inner thigh. I slapped myself in the hand, the arm, the face. Stay awake!

I laid Maggie on the floor and hopped around the house. I did jumping jacks. I jogged in circles. I pulled my hair. I pinched. I slapped.

I started to doze while I fed Maggie, a kind of darkness sliding across my eyes.

Lise watched Tangled like three times a day.

My mom drove up from Key West with her new husband. He was in the Navy, and they had been stationed in a big, nice house near the water. When I opened the front door, Mom handed me a giant, wrapped present. I looked at her like she was insane. There was a shiny, fuschia bow on top. I wondered how much it cost. I wondered what inspired her to buy me a present. Her birthday was exactly one week before mine. Had my birthday already passed?

“Are you okay?” she said and blew into the house. She cuddled with Lise on the couch for a few minutes then started doing dishes. “I’m making dinner,” she said. “You rest.”

She’d never acted like this before. I wondered if she’d watched a movie with one of those active, upbeat mom characters. I wondered if this was a performance for her husband or for me.

I took three ten-minute naps in between feeds and returned to the kitchen. Pots boiled. Mom’s new husband played with trucks on the kitchen floor with Lise. Mom told me to open my presents.

“I missed your birthday,” I said. “I didn’t get you anything.”

She shrugged. Years ago, this would have been basically an emergency, proof that I didn’t think about her, that she didn’t matter to me. It would take at least three hours to resolve, so many questions, so much explaining.

I mumbled that I’d paint her something and opened the present. Inside were two separate gifts. The first was a babydoll black crop top with large, white letters that said SHOW ME YOUR TIPS.

“Because you were a waitress for so long,” Mom said. “Plus the breastfeeding thing.”

The other present was a boomerang. I held it up. “Is this real?”

“Oh yeah. He thought you’d like it,” she nodded toward her husband.

“Why?”

“I have no earthly idea but it’s funny right?” She chuckled and bustled around the kitchen. Who was this woman?

“Maggie’s looking at you,” she said.

I looked down at the warm body strapped to my chest. Maggie was wide awake. Her cheeks were pink. Did they look rounder? Her eyes were bright. She cooed. She had been drinking more and more, each feed, but I was afraid to believe in the progress. I laughed once, awkward, choked, loud. I felt fists of hope and despair rising in my throat. I held them there.

I fed Maggie an extra syringe. She gulped it down. Then another. Then another. Mom appeared close to my body, her face close to my face. “I think you saved her life,” she said, her voice so sincere, so sweet.

I couldn’t look at her.

Fuck off, I wanted to say. I held onto the boomerang and felt my tits tighten hard against Maggie as she nursed on the plastic syringe.

I sat down on the couch and flipped through some hippie book about breastfeeding, thinking about how new moms read books and ask questions and research and talk and talk, trying to map out how to be the best kind of mother. It feels like we’re building a map with invisible ink and dissolving paper. It feels like every decision we make to take care of babies and children might be counted as exactly right to one person and exactly wrong to another. There’s no right way to be a mother, the ladies in mommy groups said. Just be a good enough mother.

For more than ten years, I’d tried to convince myself that my mom was good enough. It shouldn’t matter that she had failures—her addiction to cocaine, the way she left me and my brother after Dad died, the way she cut the brake lines in Dad’s motorcycle and tried to get him arrested on false charges more than once during their divorce. Those were mistakes. She had apologized for them several times over the years, calling me at two in the morning, drunk on Dos Equis, listing her failures, listing her shame. I’d forgiven her as many times as she apologized. I watched her moving around the kitchen, squatting to chat with Lise, laughing with her husband. My head felt like it was full of water.

I thought: This is what it feels like to barely make it. I remembered the way mom argued with my dad, usually upset with him for not giving her the kind of attention she expected after he got home from work. I’m not a fucking martyr, she said. I refuse to give up everything for this family.

For more than ten years, I’d tried to convince myself that my mom was good enough.

Maggie fell asleep against my chest, and I thought about Joan of Arc, the faceless, short haired gal I imagined when I heard the word martyr. She died because she wouldn’t stop worshiping. I imagined living a life that allowed me to even consider what or who I would like to worship. I wondered what the word worship even really meant. To adore something. To honor something so much that you spend all of the minutes of your life building a shrine to it, praying to it. I thought about the people who build and maintain pyramids and temples. I thought about monks and nuns. Were any of them actually living their lives? Or was it just pretend, a show, a theater production of a life to prove that their god is worth paying attention to?

I wondered what, if anything, I would worship if my kids were thriving, if my husband ever came home at all. I tried to remember my life before these ten-minute feeds. What did I do? What did I love? I nannied for other families, cleaned houses, wrote unpaid articles for a local news journal. If I wanted anything, it was more time to illustrate and write. I worked my ass off to get it. I worked my ass off to stay pregnant, to not lose Maggie the way I had lost my first, stillborn baby. I worked my ass off to pay the bills and feed my toddler and get through the next shift, the next meal, the next morning. Had I ever worshipped anything at all? I closed my eyes: don’t fall asleep wake up in ten minutes please survive.

I wondered how long our savings would last. My last shift at my nanny job happened a day prior to packing the U-haul and moving back to Florida. I wondered how I could work if Maggie didn’t start to eat like a regular baby. I wondered if Hurst would step up and enroll in college like he’d been supposedly aching to do since before I met him. I wondered how long a human body could stay awake before collapsing. I wondered if I was making choices, if I had any choices other than filling up the syringe when the ten-minute timer went off in my pocket. I wondered if either of us would survive.

“You made the choice,” Cherry said, the day we arrived in Florida, watching the movers stack boxes in the living room of our tiny, empty rental. She sounded ominous, like this was the beginning of a horror movie, and everyone in town but us knew our house was haunted. We could try to outsmart the ghosts, we could fight them with our whole bodies, we could even try to love them, to invite them in, to live alongside them, but the outcome would be the same. “This is what happens when you have babies without the money to raise them,” she said. “This was a choice you made.”