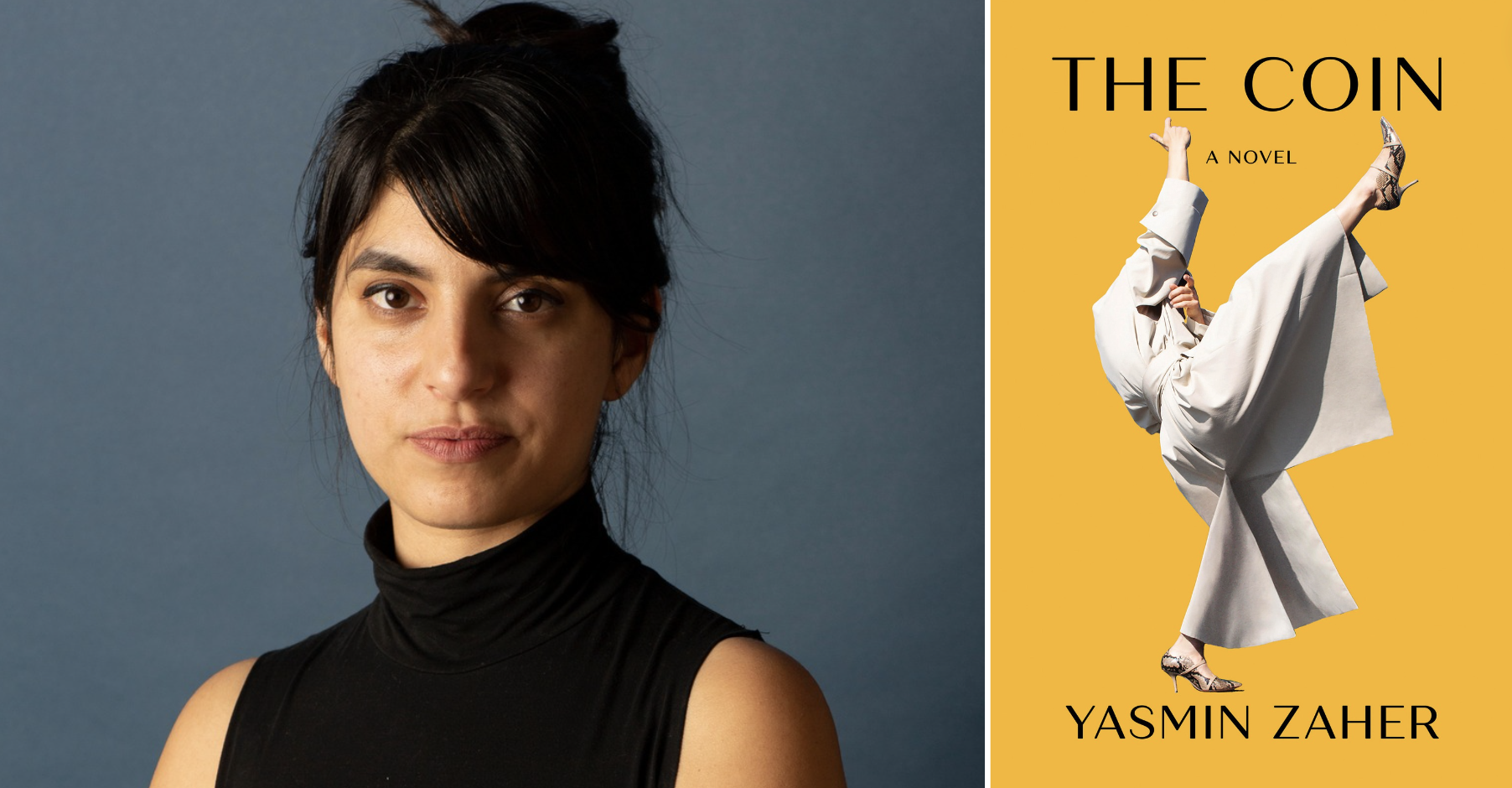

Yasmin Zaher’s debut novel, The Coin, is a worthy addition to the rich canon of novels about women losing their minds in New York City. The Coin tells the story of a wealthy Palestinian woman living in Brooklyn who slowly unravels while (questionably) teaching middle school boys, obsessing over her own hygiene, and getting caught up in a scheme reselling Birkin bags. I talked with Zaher, who is based in Paris, about moralization, journalism, and Hermès.

Anu Khosla: The unnamed protagonist in your novel seems very convinced of her own goodness. What was it that you wanted the reader to take about this idea of goodness?

Yasmin Zaher: I wrote this book during Trump’s first election, and I was living in New York for the first time in my life. It was a very moralizing moment: There were good people and bad people, and there were good writers and writers who were getting canceled. Although the character is believing in her own goodness, she’s also saying some things that would be questionable. In early drafts of the novel, she was even more politically incorrect and even more expressive of the things that many in contemporary American culture would consider not good. I was brushing against these moral boundaries of what is good and what is not good and who is completely not racist. I don’t know anyone like that.

AK: You’ve been in Paris for a year now. Did your move to there have to do with any of your experience of American moralization?

YZ: I moved here because I married a Parisian, but it’s very different. For example, probably one of the bestselling authors in France, Michel Houellebecq, is a flagrant Islamophobe. There are other examples, too—the anti-Me Too movement in France, et cetera. Morality is taken here very differently than it is in New York. But no, I didn’t choose one over the other. They’re both bad. What can I say? There’s not one that is better than the other, it’s just a different attitude to your dirty laundry. And it’s good that I use this metaphor, dirty laundry, because we are all dirty. The narrator is obsessed with cleanliness.

AK: There’s so many ways one might write a Palestinian novel or a New York millennial novel. How did you land on a project of capturing a woman’s mental unraveling on the page?

YZ: I think The Coin is more of a New York novel than a Palestinian novel. The mental unraveling is more of a thing of women of my generation who live in big Western cities than what you would expect from a Palestinian novel. I was writing what I was going through, which is that New York struck me as a very scary place, and I supposedly come from a scary place. I was just trying to express my own experience of that city. That’s what came up for me. It’s like a psychosomatic madness. It’s become maybe out of fashion to write books about women unraveling in the big city, but there’s a reason why there are so many of those books, and that’s because there are a lot of women unraveling in the big city. It’s a defining characteristic of our time.

AK: What can you do or say through a novel that you couldn’t do in your journalism?

YZ: This is going to sound absurd, but in a novel, you can say the truth, and in journalism, you cannot. My next novel takes place in a newsroom. I’m going to put out all of my frustration in this profession, and all of my admiration for it too, but a lot of my frustration. I’m going to express it in the next one.

They seem to be doing something similar, but they are, in fact, doing very, very different things. As a journalist, you cannot tell your own truth. It’s constant suppression of yourself. There’s a moment in your career when you realize that there are many obstacles to expressing yourself openly. Part of those obstacles is the rigor of the profession, of course, that you need to deliver the facts, not what you draw from the facts. I found it very frustrating. I think I belong more in fiction than in journalism.

AK: What was the research process that went into the scenes of shopping for an Hermès bag?

YZ: I did a three-month writing residency in Paris. I was just bored, I was looking for what you can do when you don’t have the right to work in a country. I saw tons of ads looking for women to shop for Hermès bags in Paris. So I answered an ad, I went, they took my passport, they gave me the cash, and I tried a couple of times. It was impossible. At the end, I got something much better out of it than €500. I got a great idea for the book. It says so much about us as a society. It says so much about class and about fashion and about performance. It’s shocking, really. Afterwards, in terms of research, I started reading more about the subject. I even read a book about marketing and luxury goods. It’s not business, it’s really sociology.

AK: How are you experiencing the timing of this novel, given that it is coming out at a moment that Palestine is so much in people’s minds?

YZ: Even if we put the Palestinian thing aside, to me, this novel reads very pre-Covid. That was something that was concerning me during the years of editing. Then I asked myself, is it a pre-October 7th novel as well? The truth is that I feel like it can still stand in terms of the politics that we’re seeing today. It doesn’t feel, to me, politically anachronistic. But there’s one line where she talks about Gaza, and she says that she heard in the news that 50 people were killed in Gaza, something like that. At the time that I wrote that, it was a day when that sounded like a very big number. Today, that is a normal number, even a low number. That’s the only part of the novel where I feel like it dates it as a pre-October 7th novel.

Personally, the timing is very strange. I’ve had a very challenging year, but it’s also one of the happiest moments of my life. I’m also getting a lot of publicity for being Palestinian, but I’m not at all representing what is going on right now. So yeah, mixed feelings.

AK: There’s this idea in the book around art and creation as an attempt to escape our identities. Of course, that’s always a futile exercise. Was this an intentional idea for you?

YZ: The narrator camouflages her racial inferiority by dressing very well and by acting in certain ways and wearing a lot of perfume. There’s an idea of using whatever you can to escape the inferior role in which you were born into in society. With art it’s funny. If it’s good, I would hope that it frees you from that. If it’s bad, then yeah, I can see that it can be just another layer of hiding your true self. I think if you’re writing from an intuitive, true place, and you’re writing about what touches you, and you’re writing about what you care about, then inevitably the book is going to have a subconscious. This book has an enormous subconscious, and I still discover things about it all the time that were hidden from me.